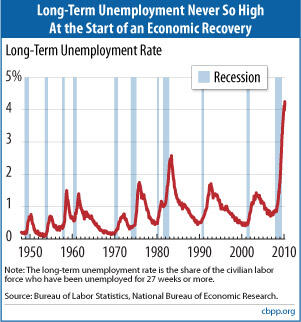

The long-term unemployment rate — the percentage of people in the work force who have been out of work for over half a year and are still looking for a job — reached an unprecedented 4.3 percent of the labor force in March (see the chart). Yet Congress has allowed the Recovery Act measures that provide additional weeks of unemployment benefits and subsidized COBRA health insurance coverage for unemployed workers to lapse. Opponents’ arguments that these measures should not be extended unless they are paid for with cuts in other spending do not withstand scrutiny. Meanwhile, delay imposes unnecessary hardship on the long-term unemployed and weakens the economic recovery.

Unemployment Insurance, COBRA, and State Fiscal Relief Provide Needed Economic Boost

Although there are growing signs that the economy is in the early stages of a recovery, unemployment remains very high, and the economy is not running on all cylinders. Demand for goods and services remains far below what the economy is capable of producing, and the rate of job creation anticipated over the next several months will represent only a small start toward restoring the 8.2 million jobs lost since the recession started. (That loss essentially erased all of the jobs created between 2003 and 2007 in the economic recovery that followed the previous recession.)

Under these circumstances, the key to boosting economic activity and strengthening the recovery is to create additional demand. And the best place to start is by extending the Recovery Act’s UI and COBRA provisions to the end of the year and providing additional fiscal assistance to cash-strapped states, which pending jobs legislation would do. These measures are widely recognized as highly effective ways to boost economic activity and create jobs. Providing financial relief to unemployed workers who will be forced to cut consumption sharply if they cannot continue to receive UI benefits to replace part of their lost income does this directly. Similarly, providing fiscal relief for cash-strapped states reduces the amount of demand-reducing, job-killing budget cuts and tax increases the states otherwise will have to enact to meet their balanced-budget requirements.[1]

Congress allowed the UI/COBRA provisions to lapse at the end of March because Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) said he would block all spending bills that are not paid for. Basic economics indicates, however, that Senator Coburn’s argument — that “the problems are so severe in our country, our debt is so severe and the impact is so great in the near and long term”[2] — is not applicable to the measures under consideration.

- The impact of a $150 billion jobs bill on the economy is strongly positive in the near term, while the impact on our long-term fiscal problem is insignificant .

As noted above, measures in the jobs bills under consideration, including extension of UI/COBRA to the end of the year and continuing fiscal assistance to the states, are widely recognized as effective measures to boost economic activity and create jobs in an economy with substantial excess unemployment and productive capacity. These measures are strictly temporary, and the history of past recessions and recoveries shows that they have always been allowed to expire once a strong and sustainable economic recovery is underway. Because these measures are temporary, they do not add significantly to the long-term budget deficit. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimated a year ago, for instance, that a stimulus bill with temporary policy changes that would cost about $800 billion in the short run would account for only about 3 percent of the projected long-run budget gap through 2050.[3]

- Contemporaneous efforts to reduce the deficit defeat the purpose of efforts to stimulate a weak economy.

For Congress to require contemporaneous cuts in federal spending or tax increases so that measures to boost the economy do not increase short-term deficits would be unwise and counter-productive — it would reduce the overall demand for goods and services and thereby partially or fully cancel out the very economic boost that the recovery measures are designed to provide. Legislation that includes offsets that take effect only after the economy is fully back on track would not cause this problem to occur. But, requiring their inclusion could make it impossible for Congress to pass the legislation in the first place, particularly given the need for 60 votes in the Senate to pass virtually any measure. [4] And if the choice is between instituting temporary measures to shore up the economy even if the measures are not paid for and taking no action (because the cost of the measures is not offset), the answer should be clear cut. Since the economic benefit of temporary measures such as extending UI benefits and state fiscal relief would be substantial while the impact on the long-term deficit would be very small, Congress should not hesitate to enact such measures.

- Restricting the search for offsets to spending cuts does not make sense economically.

To be sure, in the best case scenario, policymakers would include provisions in the jobs bills that offset the short-run increases in the deficit with savings that would take effect after the economy is fully back on track (perhaps in 2015), so that the legislation would not have even a small impact on long-term deficits. And if including such offsets were politically feasible, it would be unwise to limit the search for offsets to spending measures; budget savings achieved through eliminating tax loopholes and inefficient tax expenditures are every bit as valuable as those achieved by cutting wasteful spending. Serious analysts recognize that solving the long-term deficit problem will require measures on both the spending and revenue sides of the budget; the same principle applies to finding offsets in the intermediate term. Nevertheless, many of the lawmakers who insist that extensions of UI benefits and state fiscal relief must be paid for also insist that only spending reductions constitute acceptable offsets. These lawmakers often also assert that while temporary spending on unemployment benefits for jobless workers must be offset, permanent tax cuts need not be.

- Not paying for measures like extending UI/COBRA to the end of the year does not violate PAYGO.

Some opponents of measures like extending UI to the end of the year argue that lawmakers who support extending UI, COBRA, and state fiscal relief without offsets are guilty of hypocrisy and of shamelessly maneuvering to circumvent the very pay-as-you-go law they voted for only a few months ago.

Such charges are groundless. Most PAYGO proponents have always said that the PAYGO rules can be waived in situations like those when temporary measures are needed to respond to an economic downturn. The new PAYGO statute specifically exempts emergency measures from the PAYGO strictures, and the temporary measures needed during economic downturns have long been understood to be the type of measures that should qualify. To ignore this component of the PAYGO law, and to try to use the law to block counter-cyclical measures to help a weak economy recover, would be to use the law in a way that would weaken the economy rather than strengthen it.