- Home

- Administration’s Corporate Tax Reform Fr...

Administration’s Corporate Tax Reform Framework a Promising Start but Falls Short on Raising Revenue

Revenue Neutrality Is Not Sufficient to Help Address Nation’s Deficit Problems

The Administration has advanced a coherent framework for corporate tax reform that could lead to a more efficient corporate tax regime. [1] The framework's main weakness is that it seeks no deficit-reduction contribution from corporate tax reform, aiming only for revenue neutrality.

Given the nation's serious long-term budget problems and the painful sacrifices that policymakers will have to impose to put the budget on a sustainable path, it is imperative that all parts of the budget be on the table. A key test of well-designed corporate tax reform, therefore, is that it contributes to long-term deficit reduction; the Administration's framework falls short in this critical area. The framework also lacks detail on how to achieve its revenue-neutrality goal.

To its credit, the Administration's framework addresses the other key tests of successful corporate tax reform. [2] It would impose a minimum tax on the overseas profits of U.S.-based firms to correct the tax code's tilt in favor of overseas investments and to reduce corporations' incentives to shift domestic profits to tax havens. It calls for reducing the tax code's bias toward debt financing of corporate investments and for achieving greater parity between the tax treatment of large businesses with different corporate structures. Finally, it calls for the elimination of certain industry-specific tax subsidies.

Framework Points to Important Areas for Broadening Tax Base

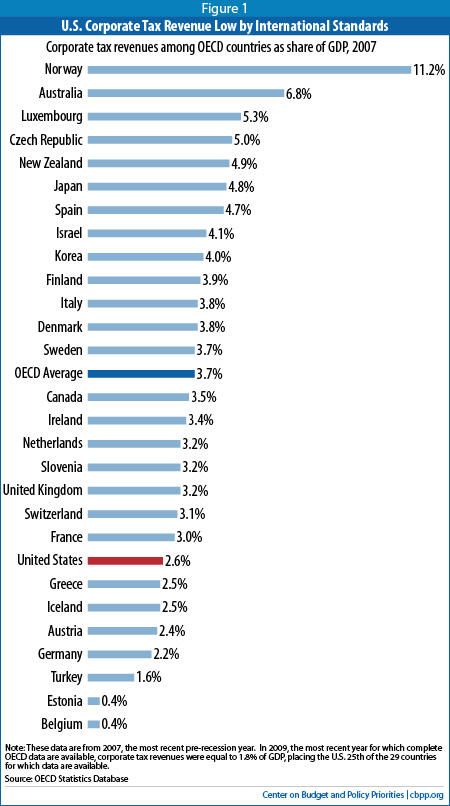

The United States has a high statutory corporate income tax rate compared to other wealthy countries. Yet, because of the tax code's many deductions, credits, and other writeoffs, it raises less revenue as a share of the gross domestic product (GDP) than most other members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Corporate tax revenues in the United States equaled 2.6 percent of GDP in 2007, placing it 21 st of the 28 OECD countries for which data are available (see Figure 1).

This juxtaposition of a high statutory rate and a narrow tax base makes the corporate income tax ripe for efficiency-enhancing reform. The Administration's framework calls for lowering the top corporate tax rate and significantly broadening the corporate tax base in several potential areas:

- Taxing corporations and large "pass-through" entities similarly. Certain businesses — partnerships, sole proprietorships, and S Corporations — are exempt from the corporate income tax. Whereas C Corporations pay corporate income taxes and their shareholders pay taxes on dividends, owners of "passed through" entities only pay tax at the individual level.

In recent decades, the share of business activity conducted by pass-through entities has increased steadily, leading to a major erosion of the corporate tax base. (As the Administration highlights, roughly three-quarters of business income was subject to the corporate income tax in 1980, but only about one-quarter is today.) Tax reform should address this erosion and restore the integrity of the corporate income tax. Reform also must ensure that large pass-through businesses and C corporations pay a similar overall rate of tax so that taxes do not drive business owners' decisions about how to structure their firms, which is economically inefficient.

The Administration proposes that consideration be given to establishing greater parity between the tax treatment of corporations and that of pass-through entities, in order to "help improve equity, reduce distortions in how businesses organize themselves, and finance lower tax rates."

- Reducing the tax code's bias toward debt financing. The current tax code is biased in favor of debt financing. When a corporation issues debt to finance an investment, its interest expenses are fully deductible, but when it finances an investment with equity (e.g., by selling shares of stock), the value of the dividends that it pays to investors is not deductible. This means that the tax code biases corporations' financing decisions in favor of a greater reliance on debt. This generous tax treatment of debt — effectively a taxpayer subsidy — plays an important role in the economics of leveraged buyouts.

The debt bias is particularly troubling given that, as tax analyst Martin Sullivan recently observed, "If we have learned one lesson from the Great Recession, it is that too much debt can be devastating to a business. Higher debt increases the possibility of financial distress for the firm, and that distress imposes real costs."[3] Tax reform needs to address the tax code's tilt toward debt over equity.

- Reducing the tax code's bias toward overseas investment. The current tax code is biased in favor of overseas investments and creates incentives for companies to shift profits to tax havens. This is because the foreign profits of subsidiaries of U.S. multinational corporations are not subject to U.S. tax until they are "repatriated," or paid back to the U.S. parent company.

To reduce this incentive, the Administration framework calls for imposing a minimum rate of tax on income earned by subsidiaries of U.S. corporations operating abroad. This minimum rate, which the Administration has not specified, must be set high enough to remove incentives for corporations to shift operations and profits overseas.

This critical aspect of the Administration's framework stands in stark contrast to proposals to set the U.S. tax rate on foreign profits at zero. A zero U.S. tax rate on foreign profits (i.e., a strictly "territorial" tax regime) would be an extremely strong incentive to shift profits and production overseas.

The Administration is to be commended for highlighting these areas, which are ripe for reform. But the framework does not advance specific proposals in any of them.

By contrast, the framework is very specific about cutting the corporate rate to 28 percent. While it also includes some specific revenue-raising proposals (e.g., eliminating tax preferences for oil and gas production and treating carried interest as ordinary income), they would not raise nearly enough revenue to pay for the proposed rate cut and the retention of other corporate subsidies that the framework favors (e.g., for research and development), as the framework itself acknowledges.

The Administration concludes that paying for its revenue-losing provisions would require, in addition to the specific measures it contains, such steps as: (1) ensuring that companies get to claim tax deductions for depreciation only to the extent that their assets truly are depreciating; (2) reducing the bias toward debt financing; and (3) taxing pass-through entities more fairly as compared to corporations. It is a positive step that the Administration highlighted these areas, but specific proposals in these areas will be needed as the tax-reform process moves forward.

Corporate Tax Reform Should Raise Revenues

The main shortcoming of the Administration's framework is its revenue target. All else being equal, corporate tax reform that is revenue-neutral would be an economic positive. All else, however, is not equal. The United States faces unsustainable long-term budget deficits that risk compromising future economic growth. Policymakers will face wrenching choices that, among other things, are likely to put downward pressure on investments in science research, infrastructure, and education — areas where well-designed investments hold promise of boosting productivity and hence future economic growth. The corporate sector itself has a stake both in the nation's long-term fiscal sustainability and in adequate productivity-increasing investments.

Given the sacrifices that policymakers are considering in virtually every other part of the budget — from Medicare to defense —- corporate tax reform should also contribute to deficit reduction.

End Notes

[1] The President's Framework for Business Tax Reform, A Joint Report by the White House and the Department of Treasury, February 2012.

[2] Chuck Marr and Brian Highsmith, "Six Tests for Corporate Tax Reform," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 28, 2011.

[3] Martin A. Sullivan, "Romney's Other Tax Break," Tax Notes, January 23, 2012.

More from the Authors