Statement: Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the August Employment Report

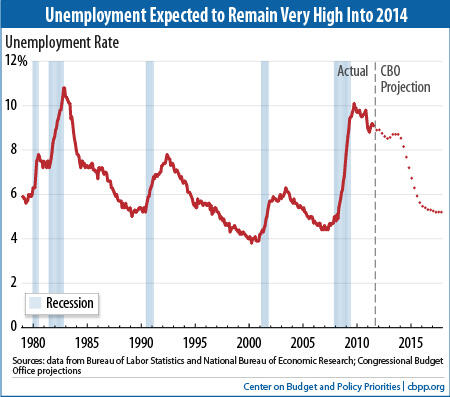

Today's jobs report highlights the critical need for policies to put people back to work. Employers added no net new jobs and the unemployment rate remained 9.1 percent. Most leading forecasters in government and out expect the unemployment rate to remain very high for the next few years (see chart). To date, policymakers have focused far more on the budget deficit than the jobs deficit. Today's report demands that they shift their attention more to the jobs deficit even while they continue working on policies that will address the long-term fiscal challenge.

In its Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update (the so-called "August update"), the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the unemployment rate would not fall below 8 percent until mid-2014 and, even with the projected sharp drop thereafter, would not reach 5.2 percent (CBO's estimate of full employment) until early 2017. The White House Office of Management and Budget has roughly comparable estimates in its Midsession Review that it released yesterday, including an alternative forecast incorporating new signs of economic weakness and showing the unemployment rate averaging 9.0 percent in 2012. As the chart shows, the excess unemployment associated with the 2007-2009 recession and subsequent protracted economic slump dwarfs that seen in the worst previous postwar recession of 1981-82.

The joint congressional committee that the recent debt-limit agreement established has the authority to meet its deficit reduction target for the next ten years by allowing additional spending and tax cuts to boost the economy and create jobs in the first few years, offset by a sufficiently large balanced package of revenue and spending measures to take effect in later years when the economy is stronger. That would be a real contribution to the debate over how to create jobs.

About the August Jobs Report

Job growth ground to a halt in August, and the labor market remains in a deep slump.

- Private and government payrolls did not increase at all in August. Private employers on net added only 17,000 jobs (about 45,000 telecommunications workers were on strike, however, depressing the private payroll numbers). The decline of 17,000 government jobs reflected a loss of 2,000 federal jobs, a gain of 5,000 state government jobs, and a loss of 20,000 local government jobs. State and local job losses would have been even larger without the return of about 22,000 workers from a partial government shutdown in Minnesota.

- This is the 18th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 2.4 million jobs (a pace of 133,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 1.9 million jobs over the same period, or 105,000 a month. Growth of 200,000 to 300,000 jobs a month or more is typical in strong economic recoveries, so the modest pace of just 40,000 jobs per month over the last four months is deeply disappointing.

- In August, despite 18 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 6.9 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls than when the recession began in December 2007, and 6.4 million fewer jobs on private payrolls.

- The unemployment rate remained 9.1 percent in August, and the number of unemployed edged up to 14.0 million. The unemployment rate was 8.0 percent for whites (3.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 16.7 percent for African Americans (7.7 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 11.3 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (5.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force, and we have yet to see a sustained return to labor force participation (people aged 16 and over working or actively looking for work) that would mark a strong jobs recovery. Over the last six months the labor force has grown by just 58,000 people per month, not even keeping up with population growth, and the number of people with a job has grown by just 9,000 per month. The labor force participation rate edged up to 64 percent in August, but is lower than it was at the start of the year and remains at levels last seen in 1984.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s, was 58.2 percent in August and has not been above 58.5 percent in 15 months.

- It remains very difficult to find a job. The Labor Department's most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking and people working part time because they can't find full-time jobs — was 16.2 percent in August, not much below its all-time high of 17.4 percent in October 2009 in data that go back to 1994. By that measure, more than 25 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Over two-fifths (42.9 percent) of the 14.0 million people who are unemployed — 6.0 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.9 percent of the labor force. Prior to this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.