BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Update, March 6: we’ve updated this post with revised data from the Urban Institute.

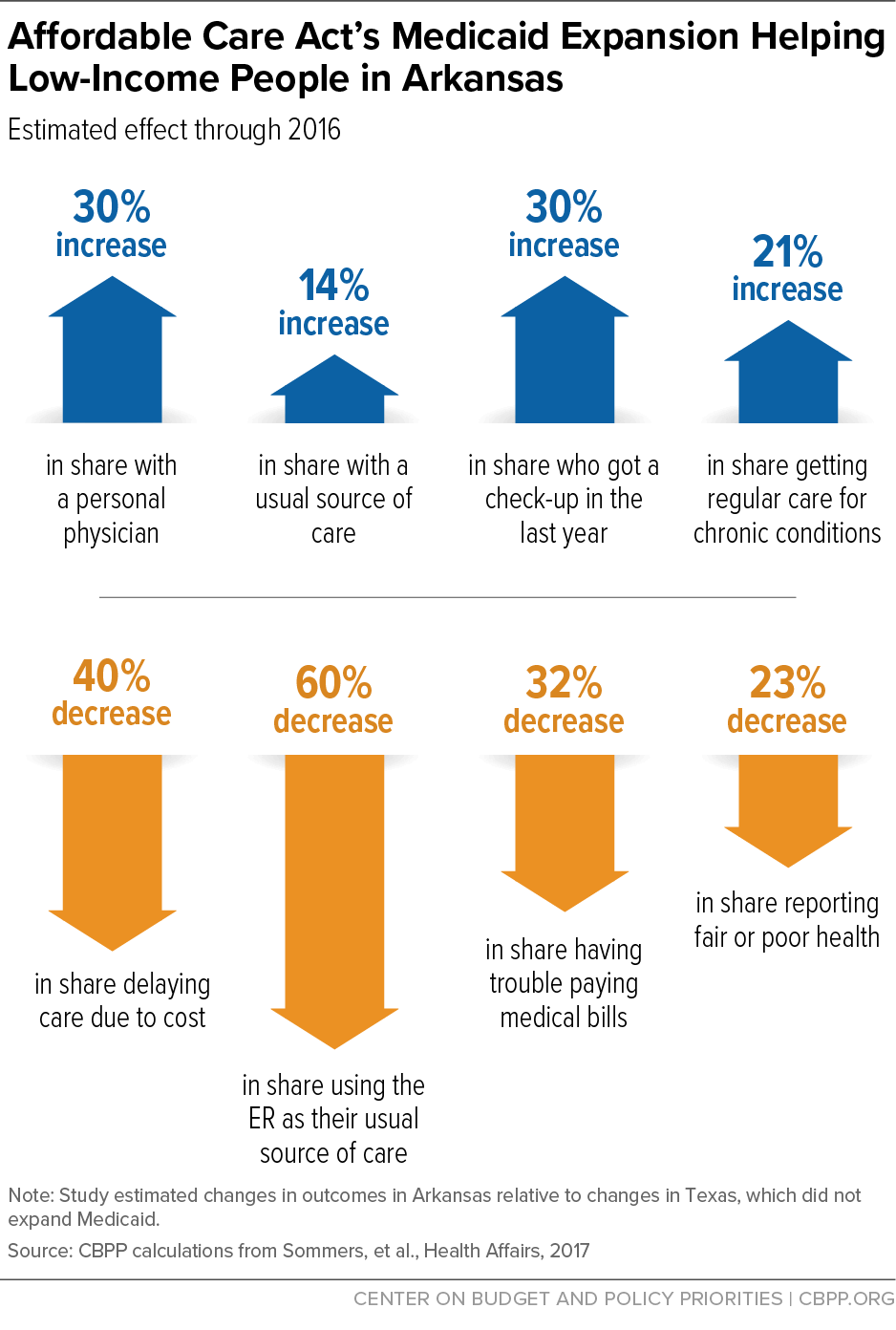

The Trump Administration’s approval today of Arkansas’ harsh work requirement inMedicaid will likely set back the state’s considerable progress under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in increasing coverage and improving access to care, health, and financial stability for low-income Arkansans (see first chart). The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approved Arkansas’ request to impose work requirements on most adult Medicaid beneficiaries, although it did not act on Arkansas’ request to end Medicaid coverage for adults with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the poverty line, which would also cause harm.

Before the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, Arkansas’ Medicaid program only covered parents with incomes below 13 percent of the poverty line and didn’t cover childless adults at all, so very few adults qualified. But by the end of 2016, Arkansas covered over 330,000 newly eligible adults through the expansion, which helped cut the number of uninsured in half from 2013 to 2016. Instead of Medicaid coverage, most of these adults got individual market coverage through the marketplace under Arkansas’ “private option” Medicaid waiver. (Those deemed “medically frail” — about 7 percent of adults according to the state’s most recent report — receive coverage through fee-for-service Medicaid outside the waiver.)

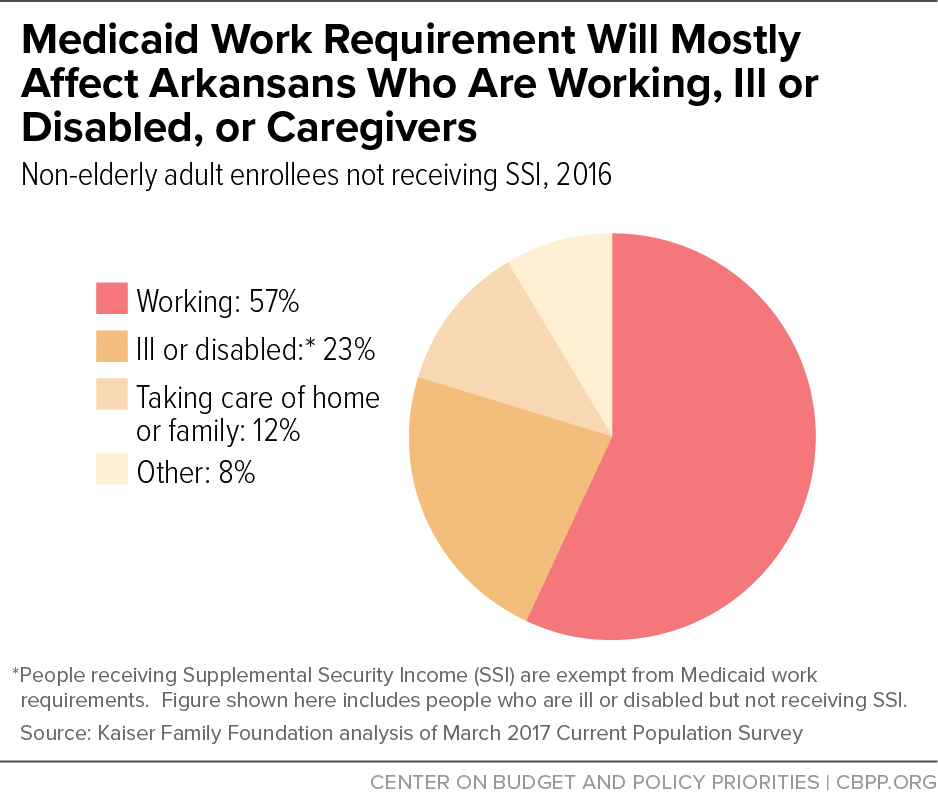

With today’s CMS announcement, Arkansas starting as soon as June will require all adults under age 50 covered through this waiver to work or participate in work-related activities for 80 hours a month, unless they prove they are exempt from the work requirements. Almost 60 percent of Medicaid expansion enrollees in Arkansas already work, and over half of the rest are ill or have a disability (see second chart). These facts might seem to suggest that the new policy will affect relatively few people but, in reality, both workers and people who are supposed to be exempt will likely lose coverage. Here’s why:

Those with disabilities or other health problems that keep them from working 80 hours each month will find exemptions hard to get and keep; according to the state’s application, they’ll have to prove they’re still exempt every two months. The same goes for people claiming they can’t work because they’re caring for an incapacitated person, such as a family member with a severe disability, or participating in a behavioral health treatment program. Studies show that red tape and paperwork requirements reduce enrollment in Medicaid; getting doctors’ letters or other proof will be burdensome both for enrollees and providers, even more so when it’s required every two months.

Many working people will also have trouble demonstrating compliance with the work requirement. By the fifth of each month, enrollees will have to log in to a state website and report that they participated in work or work-related activities for at least 80 hours the previous month, or the state will treat them as failing the work requirement for that month. Those failing to meet the requirement for three months during the year will lose coverage for the rest of the year and won’t be able to re-enroll until the next year, when they will have to reapply. Consequently, people could be locked out of coverage for up to nine months.

This approach introduces new, burdensome red tape for all enrollees, but electronic reporting will pose a particular challenge for people without Internet access. In Kentucky, 19 percent of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees lack any Internet access, and 42 percent don't have broadband access, recent research shows; access to the Internet in Arkansas is likely similar.

Along with the difficulty of monthly reporting, many people’s work hours fluctuate from month to month and will sometimes fall below required thresholds, while others will be between jobs and seeking work. For example, a retail worker who can’t get 80 hours of work in the slower sales months after the Christmas holidays could fail to meet the requirement for three months early in the year and lose coverage for the rest of that year. Also, people with disabilities or serious illnesses may lose coverage because they don’t meet the criteria for limited exemptions, don’t understand that they qualify for an exemption, or struggle to provide the documentation proving that they qualify every two months.

The inevitable coverage gaps from Arkansas’ work requirements and coverage lockouts will worsen beneficiaries’ health, which is one reason why major physician organizations oppose work requirements in Medicaid. They also undermine Arkansas’ original rationale for its “private option” expansion. The Obama Administration in 2013 approved Arkansas’ request to enroll Medicaid beneficiaries in marketplace plans in large part to test the claim that this approach would reduce enrollment “churn,” which often occurs as people go on and off Medicaid or lose eligibility altogether due to changes in their incomes and family circumstances. In its 2013 proposal, Arkansas posited that reducing churn and providing continuity of coverage and care across Medicaid and the marketplace would improve health outcomes and reduce costs. Now, the state is making a change that’s certain to increase churn and gaps in coverage, worsen health outcomes, and possibly increase state costs.