Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms Older Americans

More than 8.5 million Americans age 50-64 get health coverage through Medicaid. Many of them became eligible due to the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of Medicaid to more low-income adults, which helped drive a nearly 40 percent decline in uninsured rates for lower-income people age 50-64 between 2013 and 2016.

Now, the Trump Administration is allowing states to take away Medicaid coverage from people who don’t document that they work a specified number of hours each month. Older adults face particular challenges in meeting work requirements, and the health consequences if they lose Medicaid coverage are likely to be especially severe.

The Administration is allowing states to impose work requirements on adult Medicaid enrollees other than those who are 65 or older, pregnant, or qualify for Medicaid because they receive disability benefits through the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. In Arkansas, the first state to implement such a policy, over 18,000 Medicaid beneficiaries lost coverage in 2018 due to the new requirements. While a federal court halted Arkansas’ policy, the Administration is continuing to approve similar policies in other states. Most of these policies require enrollees to document that they work or engage in other work activities (e.g., job training or volunteer work) for at least 80 hours per month, unless they prove that they qualify for limited exemptions.

Older Adults Face Obstacles to Meeting Work Requirements

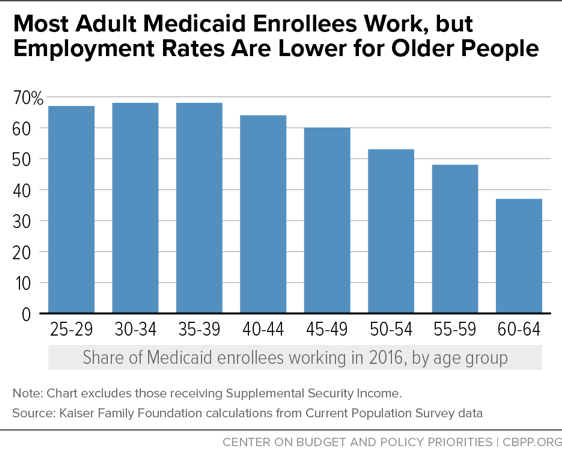

Across age groups, about 60 percent of non-elderly adult Medicaid enrollees not receiving SSI work; of the rest, about half live in working families, and more than 80 percent report that they are in school or unable to work due to illness, disability, or caregiving responsibilities. But employment rates are lower at older ages. Whereas nearly two-thirds of enrollees under age 50 work, work rates begin to fall off for those over 50, and only a minority of 60- to 64-year-olds work. (See first chart.) In addition, some working enrollees (of all ages) work part time, meaning they may not meet monthly hours requirements under work requirement policies.

There are many reasons older enrollees are more likely to be out of work. Some, especially those in their 60s, are retired. About 68 percent of all current retirees retired before age 65, and nearly half of Social Security retirees claim benefits before age 65. Hundreds of thousands of Social Security retirees age 62 to 64 depend on Medicaid for coverage. To qualify for Social Security benefits, this group must have worked much or all of their adult lives, but if Social Security is their only or primary source of income, they likely qualify for Medicaid: the average Social Security benefit for someone who retires at age 62 puts them just slightly above the poverty line for a single adult.

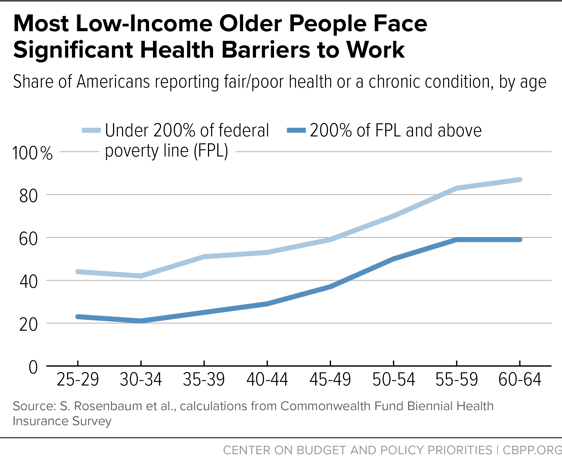

People in their 50s and 60s are also much more likely than younger people to have serious, chronic health conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, or back pain; these conditions are even more common among lower-income older people (see second chart). Such conditions generally do not qualify people for federal disability assistance, and people with these conditions may be able to work when their conditions are controlled through treatment (or are not at their most severe) or if they find a job that allows them to work part time or accommodates their physical limitations. But such conditions often still make it hard for people to maintain steady, full-time employment, putting them at risk of non-compliance with work requirements and therefore lost or interrupted coverage.

For example, Ronnie Maurice Stewart, one of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit against Kentucky’s Medicaid waiver, worked for years in mental health clinics and then as a medical assistant, but he retired once eligible to claim Social Security benefits (worth $841 per month) because he could no longer do a job that required him to be on his feet all day. Stewart, who is 62, has diabetes, arthritis, and high blood pressure and “is concerned that he will lose his health coverage if he is unable to work because of his health or if he takes a job with varying work hours,” the suit explains.

Exemptions Won’t Keep Older People From Losing Coverage

Most of the approved and pending work requirement proposals apply to older enrollees, with no exceptions for early retirees. The Administration’s work requirements guidance does instruct states that enrollees who are in compliance with or exempt from separate Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) work requirements should be treated as complying with Medicaid requirements. That approach may protect many older adults, since SNAP generally requires people 50 and over to register as looking for work but does not terminate their benefits if they cannot find a job. But millions of older Medicaid enrollees are not enrolled in SNAP and thus could still be at risk of losing coverage in states that implement Medicaid work requirements.

State waivers generally propose limited exemptions for people who are “medically frail” and for those “diagnosed with an acute medical condition” that prevents compliance. But, as AARP and other advocacy groups for older people and people with disabilities have explained, these exemptions won’t keep older enrollees with serious health conditions from falling through the cracks.

First, the exemptions are narrow, and many people won’t qualify as medically frail. Arkansas, for example, estimated that just 10 percent of expansion enrollees are medically frail. By comparison, almost a quarter of adult Medicaid enrollees not receiving SSI have a disability.

Second, even people who should qualify for exemptions may struggle to prove that they do. Obtaining physician testimony, medical records, or other required documents may be difficult, especially if beneficiaries don’t have health coverage while seeking to prove they are exempt. Red tape and paperwork requirements have been shown to reduce enrollment in Medicaid across the board, and people coping with serious mental illness or physical impairments may face particular difficulties meeting these requirements. The experience of work requirements for other programs shows that people with disabilities are disproportionately likely to be sanctioned, even though many should be exempt.

Losing Coverage Will Worsen Health — and Could Impede Employment

Losing coverage worsens health for all groups, which is why physician groups like the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and others oppose Medicaid work requirements. But the resulting coverage losses would likely be especially harmful for older enrollees because of their high rates of chronic conditions. For people with serious health needs, coverage interruptions lead to increased emergency room visits and hospitalizations, admissions to mental health facilities, and health care costs, research has shown.

And by worsening access to health care, Medicaid work requirements may actually make it harder for older people who are trying to keep working to do so. A long-term randomized trial found that providing regular care to people with heart disease increased their earnings, likely by reducing their time out of work due to illness. Conversely, making health care contingent on work is likely to result in a vicious cycle where someone who loses their job because their heart disease or diabetes worsens also loses access to treatment, making it impossible for them to regain their health and employment.