BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Low- and moderate-income working families are largely an afterthought in the House- and Senate-passed tax bills, which are heavily tilted to wealthy households and profitable corporations and add significantly to budget deficits. Addressing these fundamental flaws would effectively require the House-Senate conference committee that will iron out differences between the bills to start over and rethink the Republican approach to tax reform to this point. Since Republican leaders won’t do that, a key issue to watch is how the bill they produce complies — at least on paper — with the Senate rule requiring that the legislation can’t add to budget deficits after the first decade.

While the House didn’t try to comply with this rule, the Senate met it while making its corporate tax cuts permanent by: (1) sunsetting the tax cuts for individuals after 2025 while leaving in place various revenue-raising measures for individuals, which means that many low- and middle-income households will ultimately face tax increases; and (2) increasing the number of uninsured Americans by repealing the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) individual mandate, which requires that most people get health coverage or pay a penalty. In other words, the Senate put the interests of corporate shareholders and other wealthy investors ahead of working families, raising taxes on millions of non-affluent Americans and leaving millions to become uninsured to finance permanent corporate tax cuts. As a matter of basic decency, policymakers should reject such an approach.

To advance their tax bill, congressional Republicans used a special legislative process known as “reconciliation” that enables a bill to pass the Senate with a bare majority, rather than the 60 votes that most legislation requires, so Republicans didn’t need a single Democratic vote. And, while GOP leaders initially promised to develop revenue-neutral tax legislation, they soon reversed course and passed a budget plan allowing tax cuts that would add an estimated $1.5 trillion to deficits over the next ten years.

They then faced the Senate’s so-called “Byrd rule,” which is designed to prevent Congress from using the reconciliation process to increase long-term budget deficits. Under this rule, a reconciliation bill can’t lose money in the years after the first decade. To comply with it, Senate Republicans chose to raise taxes on many working and middle-class families and leave 13 million people uninsured to find the funds to make permanent a big corporate tax cut and a tax exemption for multinationals’ foreign profits. Here’s what the bill does in these areas:

Permanent tax cuts for corporations. The Senate bill slashes the corporate tax rate to 20 percent from 35 and sets an even lower rate for U.S.-based multinationals’ foreign profits by adopting a “territorial” tax system, which would encourage firms to shift profits and investment offshore. As Senate Republican Ron Johnson said, “With a territorial system, there will be a real incentive to keep manufacturing overseas.” Yet Senate Republican leaders made this tax advantage for foreign profits a top priority.

Permanent tax increase for middle- and lower-income households. In revising their bill, Senate Republican leaders set all of its tax cuts for individuals to expire after 2025, as well as all of its revenue-raising measures affecting the individual income tax except one: a slower inflation measure (the chained Consumer Price Index) for adjusting tax brackets and certain tax provisions each year. This permanent change would push many taxpayers, including many middle-income taxpayers, into higher tax brackets over time.

The resulting tax increases would grow each year. By 2027, the Joint Tax Committee estimated:

- 37.8 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax increases, including 8.9 million facing increases of more than $500 apiece.

- 112.0 million households with incomes below $200,000 would face tax changes of less than $100 apiece.

Millions more uninsured and higher premiums in the individual market. The Senate bill would repeal the ACA’s individual mandate. This would raise the number of uninsured Americans by 13 million by 2027 and raise premiums in the individual market by an average of 10 percent, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. Because fewer people would be insured, the CBO estimates show, federal spending for Medicaid and for federal tax credits that help low- and moderate-income Americans pay their health insurance premiums would fall by $53 billion in 2027 alone. The bill uses those savings after 2027 to help finance its permanent corporate rate cuts.

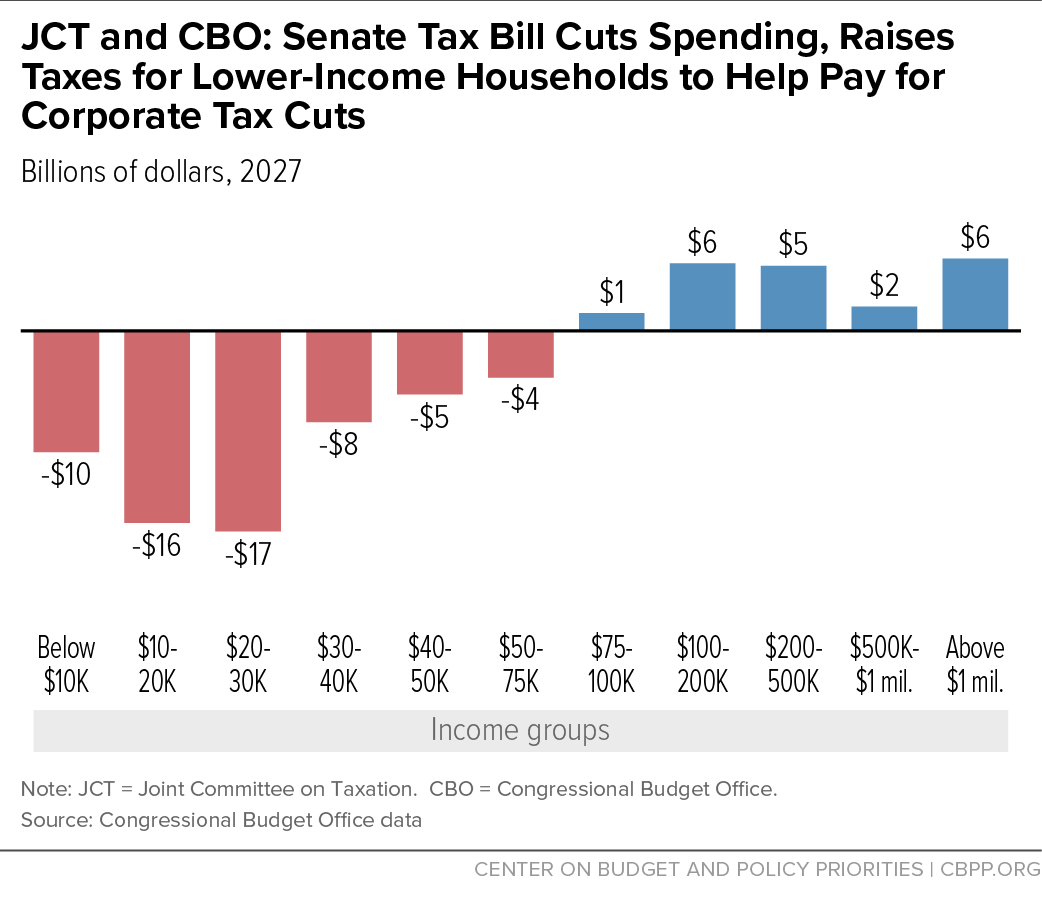

Overall, in 2027 — when only the corporate tax cuts, the slower inflation measure, and the mandate repeal would remain in place — the Senate bill would raise taxes or reduce spending for households with incomes below $75,000 by about $60 billion, while still giving very large tax cuts — through its corporate tax cuts — to those at the top, the group that owns the bulk of corporate shares and hence benefits the most from corporate tax relief. (See chart.)

While the House tax bill ignores the Senate rule that bars reconciliation bills from increasing budget deficits after the first decade (and, consequently, made all its provisions permanent), the bill that emerges from the conference committee will have to comply with the rule. In meeting it, conferees should reject the Senate approach of making working- and middle-class families pay for a permanent corporate rate cut and an even lower tax rate for U.S. multinationals’ foreign profits. They should not produce a bill that cuts taxes for big corporations by making working families worse off.