Joint Committee on Taxation Distribution Tables Confirm Skewed Priorities of House Tax Bill

End Notes

[1] JCT, “Distribution Effects Of The Chairman’s Amendment In The Nature Of A Substitute To H.R.1, The “Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,” JCX-49-17, November 3, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5029.

[2] Note that the Tax Policy Center’s (TPC) estimates include about twice as many filers with incomes over $1 million as the JCT estimates do, because TPC uses a more comprehensive measure of income than JCT. Because of this and other methodological differences, when TPC estimates the effects of the House tax bill, it will likely show a larger share of the tax cut flowing to millionaires than JCT. For the same reasons, it is difficult to directly compare the new JCT estimates with TPC estimates of earlier GOP tax proposals, such as the Unified Framework.

[3] The chained CPI raises $0.7 billion in fiscal year 2018 but $27.8 billion by 2027. The one-off tax on foreign profits raises $65.7 billion in fiscal year 2018 but loses revenue (due to the treatment of foreign tax credits) by 2027. JCT, “Estimated Revenue Effects Of The Chairman’s Amendment In The Nature Of A Substitute To H.R. 1, The ‘Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,’ Scheduled For Markup By The Committee On Ways And Means On November 6, 2017,” JCX-47-17, November 3, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5027.

[4] Chye-Ching Huang, “Doubling Exemption on Estate Tax, Then Repealing It, Would Give Millions to Wealthiest Heirs,” CBPP, November 2, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/doubling-exemption-on-estate-tax-then-repealing-it-would-give-millions-to-wealthiest-heirs.

[5] JCT distribution tables do not explicitly show percentage changes in after-tax income for each income group, the measure preferred by most tax analysts for comparing how a tax plan affects filers at different income levels. But the JCT tables do give the average tax rates — under current law and under the bill — for each income group, and percentage changes in after-tax income can be calculated directly from the change in average tax rates. For example, JCT estimates that households with incomes over $1 million would face a tax rate of 32.1 percent under current law, versus 30.6 percent under the proposal. The share of their income left after taxes is 100 percent (representing before-tax income) minus the average tax rates, so 67.9 percent for millionaires under current law and 69.4 percent under the bill. The percentage change in after-tax income can then be calculated by comparing these two estimates. For millionaires, this calculation shows that, according to JCT estimates, the House bill would increase after-tax incomes by 2.2 percent on average in calendar year 2027 (69.4/67.9 – 1 = 2.2). The JCT tables also give the dollar tax cuts for each income group under the tax proposal, allowing us to calculate the share of tax cuts going to each income group.

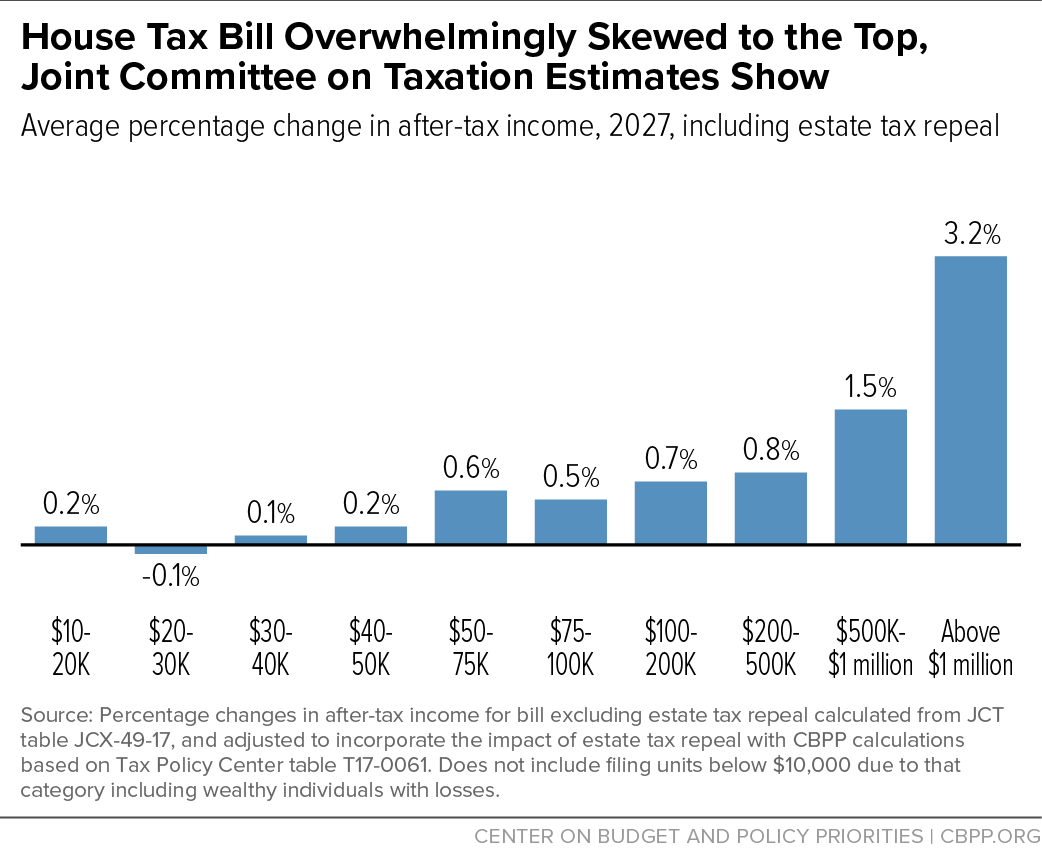

The total tax cut going to millionaires in 2027 increases from $36.6 billion shown in the JCT table to an estimated $57.9 billion when the impact of estate tax repeal is incorporated, raising their percent increase in after-tax income from 2.2 percent to 3.2 percent. To incorporate the impact of the estate tax, we first assume that the revenue loss from estate tax repeal is $38.0 billion, JCT’s estimate of the fiscal year 2027 revenue impact (JCX-47-17). (The JCT distribution estimates are based on calendar year effects, and so this fiscal year revenue estimate is conservative, as the revenues lost from estate tax repeal are growing.) We distribute this $38 billion tax cut to each income group according to the shares of the estate tax borne by each income group for 2027 in TPC Table T17-0061. We then translate that into a percentage change in after-tax income for each income group using the ratio calculated from the JCT tables, as described above.

JCT’s tables do not provide the number of filers in each income group, so we do not calculate average dollar tax changes per filer in each income group.

[6] JCX-49-17.

[7] In particular, the bill also restricts how businesses can use certain losses to offset taxes on other profits. The tax increase from this “net operating loss” provision is biggest in fiscal year 2023, but then fades away.

[8] See, Jason Furman and Greg Leiserson, “The real cost of the Republican tax cuts,” Vox, November 1, 2017, https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/10/31/16581822/republican-tax-cuts-real-costs. For an illustration of this point using the GOP “Unified Framework,” see Chye-Ching Huang and Brendan Duke, “Vast Majority of Americans Would Likely Lose From Senate GOP’s $1.5 Trillion in Tax Cuts, Once They’re Paid For,” CBPP, October 4, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/vast-majority-of-americans-would-likely-lose-from-senate-gops-15-trillion-in.

[9] Republican leaders have already indicated that they intend to use future legislation to make such budget cuts, perhaps as soon as a new reconciliation bill next year, and will use deficits to justify doing so. As Roll Call recently reported, it “interviewed half a dozen House Budget Committee members, as well as a few other fiscal hawks in the GOP conference, and they all said they anticipate mandatory spending cuts [i.e., cuts in entitlement programs] being a priority for the fiscal 2019 budget reconciliation process.” Lindsey McPherson, “On Debt Reduction, GOP Says Wait Till Next Year,” Roll Call, October 26, 2017, https://www.rollcall.com/news/politics/on-debt-reduction-republicans-say-wait-till-next-year.