- Home

- Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evi...

House Republicans will likely propose work requirements for safety net programs in their plan to address poverty, but the evidence indicates that such requirements do little to reduce poverty, and in some cases, push families deeper into it.

“First we will expect work-capable adults to work or prepare for work in exchange for receiving government benefits,” House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Kevin Brady said at a recent Committee meeting.[2] As they unveil their poverty plan tomorrow, Republicans will likely point to the 1996 welfare law, which requires cash assistance recipients to participate in work activities, as a basis for extending similar work requirements to other public benefit programs.

The evidence from an array of rigorous evaluations,[3] however, does not support the view that work requirements are highly effective, as their proponents often claim. Instead, the research shows:

- Employment increases among recipients subject to work requirements were modest and faded over time (for more, see Finding #1).

- Stable employment among recipients subject to work requirements proved the exception, not the norm (for more, see Finding #2).

- Most recipients with significant barriers to employment never found work even after participating in work programs that were otherwise deemed successful (for more, see Finding #3).

- Over the long term, the most successful programs supported efforts to boost the education and skills of those subject to work requirements, rather than simply requiring them to search for work or find a job (for more, see Finding #4).

- The large majority of individuals subject to work requirements remained poor, and some became poorer (for more, see Finding #5).

- Voluntary employment programs can significantly increase employment without the negative impacts of ending basic assistance for individuals who can’t meet mandatory work requirements (for more, see Finding #6).

Those who argue that work requirements in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program have been a major success often cite rigorous, random assignment studies (the gold standard for assessing a program’s effectiveness)[4] of mandatory work programs conducted either before TANF’s creation in 1996 or during its early years. But these claims usually don’t account for these studies’ full findings. In this paper, we re-examine the studies of these programs, assessing how individuals subject to work requirements as compared to individuals not subject to the work requirements fared over time, including whether they worked steadily and had incomes that lifted them above the poverty line. We also examine data on how recipients with significant employment barriers, including mental and physical health issues, fared. That’s important because these individuals are the least likely to find jobs on their own and have the most to gain from the employment assistance that TANF was supposed to provide. (See Appendix A for a description of the studies that we include in our analysis.)

Work requirements rest on the assumption that disadvantaged individuals will work only if they’re forced to do so, despite the intensive efforts that many poor individuals and families put into working at low-wage jobs that offer unpredictable hours and schedules and don’t pay enough for them to feed their families and keep a roof over their heads without public assistance of some kind. Too many disadvantaged individuals want to work but can’t find jobs for reasons that work requirements don’t solve: they lack the skills or work experience that employers want, they lack child care assistance, they lack the social connections that would help them identify job openings and get hired, or they have criminal records or have other personal challenges that keep employers from hiring them. In addition, when parents can’t meet work requirements, their children can end up in highly stressful, unstable situations that can negatively affect their health and their prospects for upward mobility and long-term success.

Rather than instituting or expanding work requirements, policymakers should maintain a strong safety net that can help individuals and families weather hard times — and invest more in programs that help public benefit recipients build the skills and acquire the work experience they need to succeed in today’s labor market. They also should institute employment policies that open doors for individuals with criminal records or other personal challenges and expand subsidized jobs for the long-term unemployed and those with significant work limitations who otherwise can’t secure employment (or can’t get a first job through which to acquire skills and experience and show their worth as employees). Employment increases among recipients subject to work requirements were modest and faded over time.

Finding #1: Increases in employment among recipients subject to work requirements were modest and faded over time.

Evaluations of programs that imposed work requirements on welfare recipients found modest, statistically significant increases in employment early on among recipients subject to the requirements, but those increases faded over time. Within five years, employment among recipients not subject to work requirements was the same as or higher than employment among recipients subject to work requirements in nearly all of the programs evaluated.

In the first two years, the share of recipients subject to work requirements who worked at any point over that period was significantly higher — in nine of the 13 programs included in the analysis — than the share of recipients not subject to the requirements who worked, with the increase in employment ranging from 4.1 to 15.1 percentage points.[5] (See Table 1.) The biggest impacts on employment were found in programs in Riverside, California and Portland, Oregon.

Over time, however, work steadily increased among recipients not subject to work requirements, substantially closing the employment gap between the two groups. By the fifth year (the last year any of the studies examined), the impacts of the early years had eroded in each of the programs for which longer-term data are available. In five of the eight programs that initially produced a significant increase in employment rates, by the fifth year the program recipients not subject to the work requirements were just as likely — or more likely— to work than the program recipients subject to work requirements. The net impact fell most in the Riverside LFA (labor force attachment) program,[6] from an increase of 15.1 percentage points in employment rates in the first two years to a gain of just 4.2 percentage points in the fifth year. Similarly, in Portland, the net impact on the employment rate declined from an 11.2 percentage-point increase in the first two years to a barely significant 3.8 percentage-point increase in the fifth year.[7]

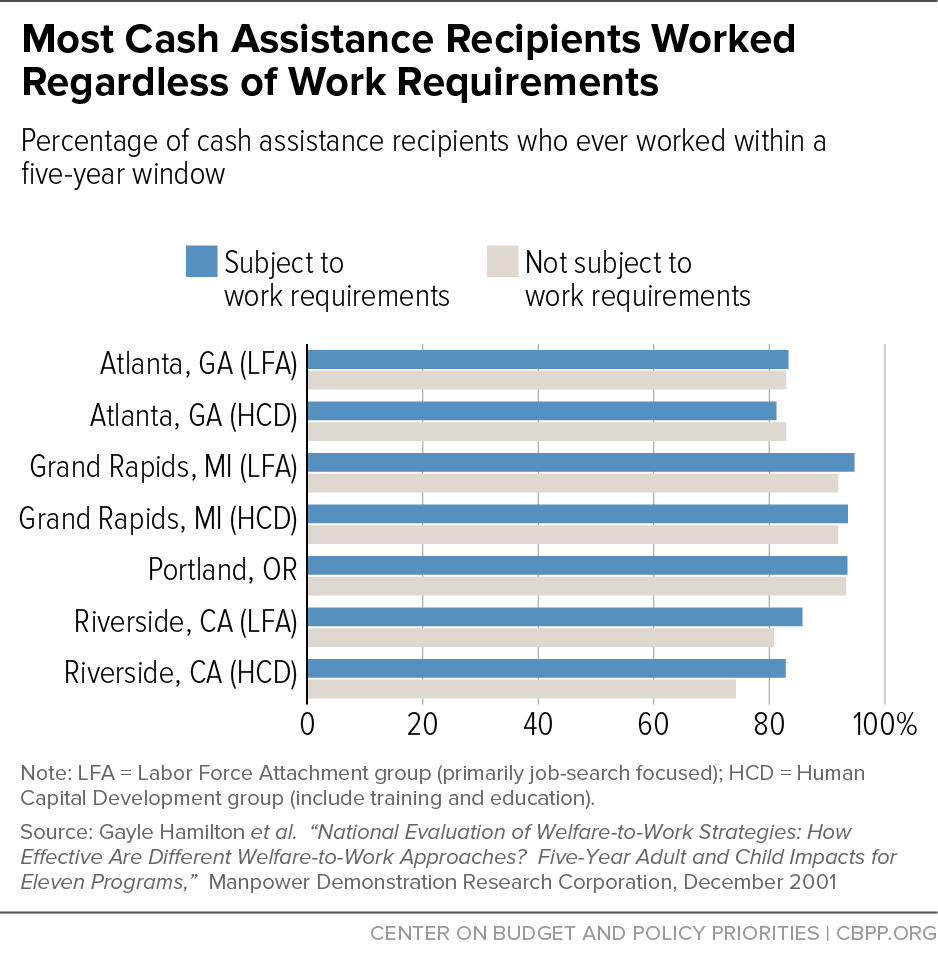

The impacts of work requirements were modest in most programs even in the early years, in part because work was far more common among recipients than is generally perceived. Over the five-year period, the vast majority of recipients worked, even if they were not subject to work requirements. (See Figure 1 and Appendix Table B-1.) In Portland, which excluded recipients with substantial employment barriers from work requirements, more than 90 percent of recipients worked over the five-year period, regardless of whether or not they were subject to work requirements. In the other sites, employment rates among recipients not subject to work requirements ranged from 74.2 to 91.9 percent. Employment among recipients subject to work requirements ranged from 81.2 to 94.7 percent.[8]

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Increases Among Cash Assistance Recipients Subject to Work Requirements Were Modest and Faded Over Time | ||||||

| Percentage of recipients who worked | ||||||

| Year 1-2 | Year 5 | |||||

| Program Name | Subject to Work Requirements | Not Subject to Work Requirements | Impact | Subject to Work Requirements | Not Subject to Work Requirements | Impact |

| NEWWS Study Sites | ||||||

| Atlanta, GA (LFA) | 66.1 | 61.6 | 4.5*** | 65.1 | 63.0 | 2.1 |

| Atlanta, GA (HCD) | 64.4 | 61.6 | 2.8** | 63.9 | 63.0 | 0.6 |

| Columbus, OH (Integrated) | 73.9 | 72.2 | 1.7 | 69.1 | 68.8 | 0.3 |

| Columbus, OH (Traditional) | 73.5 | 72.2 | 1.3 | 69.3 | 68.8 | 0.5 |

| Detroit, MI | 62.3 | 58.2 | 4.1*** | 68.8 | 68.8 | 0.0 |

| Grand Rapids, MI (LFA) | 77.7 | 70.1 | 7.6*** | 70.0 | 73.0 | -2.9* |

| Grand Rapids, MI (HCD) | 75.4 | 70.1 | 5.3*** | 70.3 | 73.0 | -2.7* |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 64.1 | 65.0 | -0.9 | 53.2 | 54.2 | -1.0 |

| Portland, OR | 72.1 | 60.9 | 11.2*** | 62.4 | 58.6 | 3.8* |

| Riverside, CA (LFA) | 60.1 | 45.0 | 15.1*** | 48.7 | 44.5 | 4.2*** |

| Riverside, CA (HCD) | 48.2 | 38.9 | 9.3*** | 44.9 | 39.9 | 5.0*** |

| Other Study Sites | ||||||

| IMPACT Basic Track (IN) | 45.3 | 44.6 | 0.7 | NA | NA | NA |

| Los Angeles, CA Jobs - 1st GAIN | 67.2 | 57.6 | 9.6*** | NA | NA | NA |

*, **, and *** denotes statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels, respectively, with .01 being the highest level of significance.

Note: LFA = Labor Force Attachment group (programs that focus primarily on job search, also known as "work first" programs); HCD = Human Capital Development group (programs that also include skills training and education); NEWWS = National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies; GAIN = Greater Avenues for Independence; IMPACT = Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training Basic Track. The Columbus, Ohio, integrated site featured one worker providing employment case management and eligibility determination, while the traditional site featured two workers: one completing eligibility functions and one providing employment case management.

Source: Jeffrey Grogger and Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005.

Finding #2: Stable employment among recipients subject to work requirements proved to be the exception, not the norm.

Work requirements encouraged recipients to enter the labor marker sooner than they would have without them, the evidence from the studies reviewed here suggests. However, this increased employment was often short-lived. Stable employment, defined in these studies as being employed in 75 percent of the calendar quarters in years three through five, was the exception, not the norm. The share of recipients subject to work requirements who worked stably ranged in these programs from a low of 22.1 percent to a high of 40.8 percent. Even when work requirements led to a rise in stable employment, the increases were quite small. In Portland, the site of the largest impact, stable employment rose only from 31.2 to 38.6 percent.[9] (See Table 2.)

| TABLE 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Increases in Stable Employment Due to Work Requirements Were Small | |||

| Percentage of cash assistance recipients employed in 75 percent or more of quarters in years 3 to 5 | |||

| Program Name | Subject to Work Requirements | Not Subject to Work Requirements | Impact |

| Atlanta, GA (LFA) | 37.0 | 32.5 | 4.5*** |

| Atlanta, GA (HCD) | 35.6 | 32.5 | 3.1* |

| Columbus, OH (Integrated) | 43.7 | 42.4 | 1.3 |

| Columbus, OH (Traditional) | 43.4 | 42.4 | 1.0 |

| Detroit, MI | 35.9 | 34.3 | 1.7 |

| Grand Rapids, MI (LFA) | 40.8 | 38.0 | 2.9* |

| Grand Rapids, MI (HCD) | 39.8 | 38.0 | 1.8 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 22.1 | 22.8 | -0.6 |

| Portland, OR | 38.6 | 31.2 | 7.5*** |

| Riverside, CA (LFA) | 23.7 | 20.6 | 3.2*** |

| Riverside, CA (HCD) | 20.1 | 16.2 | 3.9*** |

*, **, and *** denotes statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels, respectively, with .01 being the highest level of significance.

Note: GAIN = Greater Avenues for Independence; LFA = Labor Force Attachment group (programs that focus primarily on job search, also known as "work first" programs); HCD = Human Capital Development group (programs that also include skills training and education). The Columbus, Ohio, integrated site featured one worker providing employment case management and eligibility determination, while the traditional site featured two workers: one completing eligibility functions and one providing employment case management.

Source: Jeffrey Grogger and Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005.

Two descriptive studies that examine the employment trajectories of recipients who left the welfare rolls arrive at similar conclusions. Researchers studying the employment and earnings trajectories in the late 1990s of parents who left welfare in Wisconsin found that only 19.2 percent were stably employed over a six-year period.[10] In Maryland, researchers examining the employment and earnings paths of recipients who left TANF from December 2001 through March 2009 found that only 21.6 percent of leavers were stably employed over a five-year period.[11]

Finding #3: Most recipients who had significant barriers to employment never found employment, even after participating in programs otherwise deemed “successful.”

Many recipients turn to public assistance programs because they face significant personal or family challenges that limit their ability to work or reduce their ability to compete for a limited supply of jobs. Physical and mental health conditions that limit an individual’s ability to work or limit the amount or kind of work the individual can do are much more common among public benefit recipients than among the general population, research shows.[12] With the right supports and enough time, many of these individuals likely would be able to work, but few welfare employment programs have created alternative pathways to work for them or devised effective assessment procedures that can identify them and ensure that they receive the supports and services they need to find and retain employment.

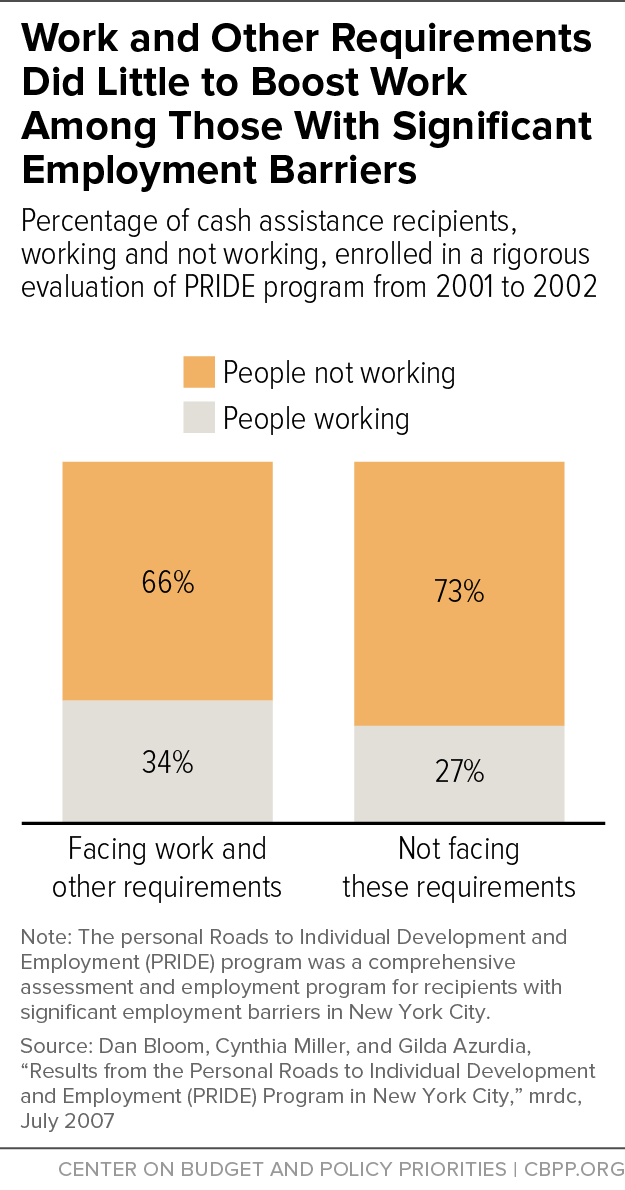

Even when special services are provided that successfully increase employment for individuals who face significant employment barriers, the vast majority of recipients participating never find employment, as the one study that explicitly examines the impact of work requirements on this group shows. (See Figure 2.) A rigorous two-year study of the PRIDE (Personal Roads to Individual Development and Employment) program in New York City — a comprehensive mandatory assessment, work experience, and job search program for recipients with significant employment barriers — found that while the program significantly increased employment among program participants relative to what it otherwise would be, the majority still never found jobs.[13] (See Figure 2.) Thirty-four percent of recipients required to participate in the program found jobs, compared to 27 percent of those who were not required to participate. But even with the intensive services the program provided, two-thirds of the recipients required to participate never found work. In addition, many of the recipients subject to the requirements ended up worse off, because sanctions for not meeting the work requirements took away their only source of cash income. About one-third of those subject to the work requirements were sanctioned compared to only about 8 percent of the group not subject to the requirements.

Finding #4: Over the long term, the most successful programs supported individuals who were subject to the work requirements in efforts to improve their education or build their skills, rather than simply requiring them to work or find a job.

In welfare reform’s early years, proponents of a “work first” or labor force attachment approach declared victory over proponents of a “human capital development” approach focused on building education and skills. This declaration in part relied on characterizing two important efforts — in Portland and Riverside LFA — as “work first” programs focused on quick entry into the market, even though both supported individuals’ efforts to improve their education or improve their skills. Both programs, which did in fact have the most significant impacts on employment of the programs discussed here, provided job search assistance but also encouraged or supported participation in education and training programs. Portland initially assigned some recipients subject to work requirements to short-term education or training programs, significantly boosting the share of the recipients subject to work requirements who increased their education or training. Although Riverside LFA focused more on getting recipients into the labor market quickly, about 30 percent of the recipients subject to work requirements participated in a post-secondary education or vocational training program.[14]

A study that re-examined the impact over nine years of several programs implemented in California in the early 1990s found that recipients participating in programs that emphasized education and training fared as well as or better than participants in programs that emphasized immediate employment.[15] Employment rates for recipients in work-first programs that focused solely on job search faded over time, while employment for participants in human capital development programs that focused on furthering skills and education increased.

A second study that followed all women who received welfare in Missouri and North Carolina between 1997 and 1999 for 16 quarters found that recipients participating in post-secondary education or training programs fared better than those who participated in assessment or job search programs.[16] Individuals engaged in post-secondary education or training had lower initial earnings, but their earnings eventually surpassed those of the job-search participants.

More recent studies have added to the evidence that participation in post-secondary education and training programs can significantly improve disadvantaged individuals’ long-term employment trajectories. For example, within two years, participants in three sectoral employment programs that prepare recipients for in-demand jobs (such as computer repair or careers in the health industry) that were evaluated as a part of the Sectoral Employment Impact Study[17] earned 29 percent more than the people not randomly selected to participate in the program. Participants in the programs studied also were more likely to be employed, be employed consistently, work in jobs with higher wages, and work in jobs that offered benefits.

Year Up, a one-year training program in information technology or investment operations for young adults, also produced significant impacts on earnings according to a recent random assignment study of the program. In the second year of follow-up, the average participant earned 30 percent more per year than individuals not assigned to participate in the program. [18]

Finding #5: The vast majority of individuals subject to work requirements remained poor, and some became poorer.

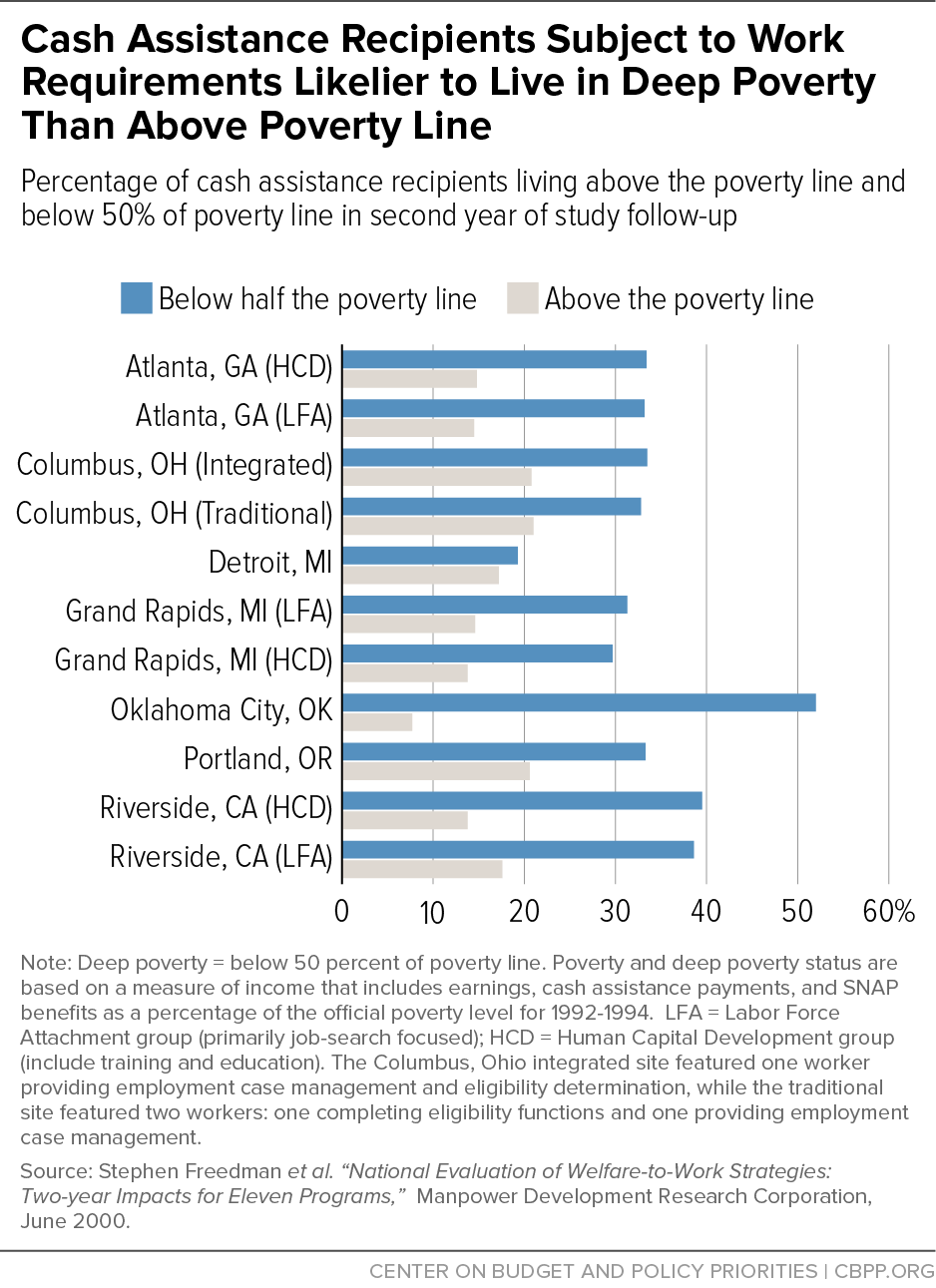

Although recipients were more likely to be employed in the first two years after becoming subject to work requirements, their earnings were not sufficient to lift them out of poverty — and in some programs, the share of families living in deep poverty increased.[19] (In these studies, poverty and deep poverty status are based on a measure of income that includes earnings, cash assistance payments, and SNAP benefits.) Regardless of whether recipients were subject to work requirements or not, they were more likely to live in deep poverty than to have incomes above the poverty line, in all but one of the sites. (See Figure 3.) Despite increased earnings, the poverty rate didn’t decline, because recipients’ earnings gains generally weren’t large enough to lift them over the poverty line and were offset in part by reductions in cash assistance payments and SNAP benefits.

Taking into account the earnings, cash assistance payments, and value of SNAP benefits, poverty rates among recipients subject to work requirements ranged from 71.1 to 92.3 percent in the second year of a two-year follow-up study. Only two programs, Portland and Atlanta HCD, significantly reduced the share of families living in poverty. Even in Portland which had the most significant drop — from 83.4 percent to 79.4 percent — the drop was small. (See Appendix B, Table B-2.) Even when the value of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is added to income and child care costs are subtracted from income, only one program, Riverside LFA, showed a significant drop in poverty among families subject to work requirements.[20]

Moreover, not only did the poverty rate remain largely unchanged in nearly all of the sites, but deep poverty increased significantly in six of the 11 sites for which data on deep poverty are available. Deep poverty among program participants ranged from 19.3 percent in Detroit to 52 percent in Oklahoma City. The biggest increase in deep poverty occurred in the Riverside programs, where it rose by 4.9 percentage points in the Riverside LFA program and 6.1 percentage points in the Riverside HCD program.

Contributing to the rise in deep poverty was an increase in the number of recipients subject to work requirements who fell off the welfare rolls even though they had not obtained a job. The share of participants subject to work requirements who had no income from either welfare or work once they left the welfare rolls ranged from 13.1 percent of the participants in Detroit to 39.9 percent in Oklahoma City. In seven of the 11 sites for which we have deep poverty data, the likelihood of a recipient leaving the welfare rolls without work was significantly higher for recipients subject to work requirements than for those not subject to the requirements.

Two other comprehensive studies that followed large numbers of recipients over several years confirmed this finding. A study in Cleveland, Ohio that followed recipients over a four-year period found that the percentage of welfare recipients with neither work nor welfare nearly doubled, from 11 percent in 1998 to 20 percent in 2001.[21] A study in New Jersey tracking former recipients for approximately five years found a steady annual percentage of 25 to 28 percent without either work or welfare. In its examination of this category of welfare leavers, the study found that 40 percent of those who were off welfare and not employed were considered the “least stable” (i.e., they didn’t live with an employed spouse or partner and didn’t receive income from other programs such as Supplemental Security Income or unemployment insurance). About a third of the “least stable” group left cash assistance due to a sanction, which was often a result of being ruled noncompliant with a work requirement — about twice as high a percentage as among welfare leavers overall. [22]

Finding #6: Voluntary employment programs can significantly increase earnings and employment for very disadvantaged individuals without the negative consequences associated with mandatory work requirements.

The primary downside with imposing work requirements on public benefit recipients is the harm they can cause to the individuals — and their families — who are unable to comply and lose essential assistance as a result. Researchers and practitioners have not devised effective strategies to identify those individuals who will have considerable difficulty complying with the requirements, with the result that some of the neediest individuals with the greatest personal challenges or other barriers to employment can be cut adrift and left with no assistance to meet their basic needs — and with little or no access to the services they need to help them improve their circumstances. The results from a rigorous evaluation of the Jobs-Plus demonstration, an employment program for public housing residents, suggest that voluntary work programs can be successful without the harmful consequences that typically accompany work requirements. Unlike most work programs that serve a limited number of people, Jobs-Plus was designed to reach all public housing residents in the public housing developments where it was implemented. In recent years, Congress has recognized the success of Jobs-Plus by providing funds to expand the program to additional locations.

Jobs-Plus is notable for both its scale and its scope. Under the program, public housing residents have access to employment and training services, as well as new rent rules that make low-wage work pay more by allowing residents to keep more of their earnings. In addition, the program takes advantage of its place-based design to develop “community support for work” by involving residents in sharing information about work opportunities. The program targets all working-age, non-disabled residents of the housing developments where it is implemented. Its strategy is to saturate public housing complexes with work-focused encouragement, information, incentives, and employment assistance. The program relies on close coordination and collaboration among local workforce, human service agencies and the public housing authorities.

Jobs-Plus significantly increased earnings for residents in several cities of different sizes and demographics, and increased employment for groups with historically low labor-force participation rates. Although the program was voluntary, about three-quarters of the residents in the four well-implemented sites[23] used its services, rent-based work incentives, or both.[24]

In a long-term follow-up in three well-implemented sites (Dayton, Ohio, Los Angeles, California, and St. Paul, Minnesota), the program produced substantial increases in residents’ earnings that were sustained for at least three years after the program ended, researchers found. Earnings for program participants were 14 percent higher, on average, over the last seven years of the nine-year follow-up period, than for the comparison group, which wasn’t offered the program services. In contrast to the mandatory work programs where earnings gains declined over time, the earnings gains in these Jobs-Plus sites grew over time.[25] In the final year of follow-up, the earnings gains increased to 20 percent. As a result of Jobs-Plus, some residents who were not employed started working, and others who were already working started working more consistently and at better-paying jobs.

The Jobs-Plus employment gains also were significant for several groups that historically have had lower-than-average employment rates. For example, employment rates increased by 4.1 percentage points for black, non-Hispanic women in Dayton, 10.8 percentage points for Hispanic men in Los Angeles, and 12.8 percentage points for Southeast Asian women in St. Paul.[26]

Appendix A

Studies of 13 programs that used a random-assignment methodology (the gold standard for evaluating social programs) and mandated participation in work-related activities form the core of our analysis. (See Tables A-1 and A-2 for program descriptions.) These studies are included in a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of welfare reform by Jeffrey Grogger of the University of Chicago and Lynn A. Karoly, a Senior Economist of RAND Corporation, two highly regarded researchers.[27] These studies commenced prior to passage of the 1996 welfare law and continued after the law took effect.

People who participated in the studies were randomly assigned to participate in either a program where they were required to work, look for work, or participate in an education or training program and could be sanctioned (i.e., their cash benefits could be terminated or reduced if they were judged not to have met the requirement) or a program where they were not simply referred to an existing workforce or education program in the neighborhood in which they lived. Eleven of the 13 studies were part of the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies, a large random assignment study of mandatory work programs, conducted by mdrc (formerly the Manpower Development Corporation), one of the leading research firms in the country.

Grogger and Karoly included two types of programs in their analysis of mandatory work programs: “work first” programs, also known as labor force attachment (LFA) programs, which focused primarily on job search; and “human capital development” (HCD) programs, which focused on participation in education and training programs.[28] Several study sites operated both types of programs; in those sites, cash assistance recipients were assigned to one of three programs — a LFA program, a HCD program, or a voluntary program that provided minimal assistance with either job search or participation in education or training.

As is true in all random-assignment studies, success is measured by whether the difference in outcomes (e.g., employment, earnings, and poverty) between the “program group” (which was subject to mandatory work requirements) and the “control group” (which didn’t participate in the mandatory work program) was statistically significant, meaning that the difference was large enough that it was unlikely due to chance. Because recipients were randomly assigned to one of the groups, the differences in outcomes are not attributable to labor-market conditions or the recipients’ personal characteristics, but rather show how effective (or ineffective) the various programs were. Statistical significance levels describe how certain we are that the difference in outcomes of the groups compared did not occur by chance and are defined as: * = 10 percent; ** = 5 percent and *** = 1 percent, with 1 percent providing the highest level of confidence that the difference can be attributed to the program.

| TABLE A-1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of Mandated Work Program Random-Assignment Methodology | |||||

| Sample Sizes | |||||

| Program Name | Cases Served | Enrollment Period | Subject to Work Requirements (Program Group) | Not Subject to Work Requirements (Control) | Total |

| Los Angeles Jobs - 1st GAIN (California) | Single parent recipients and applicants | Apr 96 - Sep 96 | 11,521 | 4,162 | 15,683 |

| Atlanta LFA (Georgia) | Recipients and applicants | Jan 92 - Jan 94 | 1,141 | 1,497 | 2,938 |

| Atlanta HCD (Georgia) | Recipients and applicants | Jan 92 - Jan 94 | 1,495 | 1,497 | 2,992 |

| Grand Rapids LFA (Michigan) | Recipients and applicants | Sep 91 - Jan 94 | 1,557 | 1,455 | 3,012 |

| Grand Rapids HCD (Michigan) | Recipients and applicants | Sep 91 - Jan 95 | 1,542 | 1,455 | 2,997 |

| Riverside LFA (California) | Recipients and applicants | Jun 91 - Jun 93 | 3,384 | 3,342 | 6,726 |

| Riverside HCD (California) | Recipients and applicants, low education | Jun 91 - Jun 93 | 1,596 | 3,342 | 4,938 |

| Portland (Oregon) | Recipients and applicants | Feb 93 - Dec 94 | 3,529 | 499 | 4,028 |

| Columbus Integrated (Ohio) | Recipients and applicants | Sep 92 - Jul 94 | 2,513 | 2,159 | 4,672 |

| Columbus Traditional (Ohio) | Recipients and applicants | Sep 92 - Jul 95 | 2,570 | 2,159 | 4,729 |

| Detroit (Michigan) | Recipients and applicants | May 92 - Jun 94 | 2,226 | 2,233 | 4,459 |

| Oklahoma City (Oklahoma) | Applicants | Sep 91 - May 93 | 4,309 | 4,368 | 8,677 |

| IMPACT Basic Track (Indiana) | Recipients and applicants less job ready | May 95 - Dec 95 | 3,090 | 766 | 3,856 |

Note: LFA = Labor Force Attachment group (programs that focus primarily on job search, also known as "work first" programs); HCD = Human Capital Development group (programs that also include skills training and education). GAIN = Greater Avenues for Independence; IMPACT = Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training Basic Track. The Columbus, Ohio, integrated site featured one worker providing employment case management and eligibility determination, while the traditional site featured two workers: one completing eligibility functions and one providing employment case management.

Source: Jeffrey Grogger and Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005

| TABLE A-2 | |

|---|---|

| Program Descriptions | |

| Program Name | Description |

| Programs Included in the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies (NEWWS) Evaluation | |

| Atlanta, GA Labor Force Attachment (LFA) | Beginning in 1992, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients and new applicants with no children under the age of 3. Most people started with job search, but if they could not find jobs after the search, they could participate in short-term adult basic education or vocational training. |

| Atlanta, GA Human Capital Development (HCD) | The program was mandatory for welfare recipients and new applicants with no children under the age of 3. Adult basic education and vocational training were the most common activities. |

| Columbus, OH (Integrated) | Beginning in 1992, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients and new applicants with no children under the age of 3. Most people received education and training. Program functions (i.e., eligibility and employment and training case management) previously handled by two workers were integrated and handled by one staff member. |

| Columbus, OH (Traditional) | The program was mandatory for welfare recipients and applicants with no children under the age of 3. Most people received education and training. Two different staff members handled eligibility and employment and training case management. |

| Detroit, MI | Beginning in 1992, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients and new applicants with no children under the age of 1. The program did not enforce the mandates as much as other programs making it more like a voluntary program. Long-term education, training, and job search were most common activities. |

| Grand Rapids, MI Labor Force Attachment (LFA) | Beginning in 1991, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients and applicants with no children under the age of 1. Most people started with job search, but if they could not find jobs after the search, they were placed in a work experience program. |

| Grand Rapids, MI, Human Capital Development (HCD) | The program was mandatory for welfare recipients and applicants with no children under the age of 1. Adult basic education, vocational training, and post-secondary education were the most common activities among participants. |

| Oklahoma City, OK | The program was mandatory for new applicants with no children under the age of 3. Case managers emphasized education and training rather than job search. |

| Portland, OR | Beginning in 1993, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients with no children under the age of 1. Recipients with significant employment barriers were exempt from participation. Case managers encouraged the less job-ready participants to pursue adult basic education and training. For others, job search for full-time jobs over the minimum wage with fringe benefits were emphasized. |

| Riverside, CA Labor Force Attachment (LFA) | Beginning in 1991, the program was mandatory for welfare recipients with no children under the age of 3. Most people started with job search, but if they could not find jobs after the search, they could participated in education or vocational training. |

| Riverside, CA Human Capital Development (HCD) | The program was mandatory for welfare recipients with no children under the age of 3. Only those who needed basic education could enroll. Therefore, adult basic education was the first activity for most people. |

| Other Programs | |

| Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training (IMPACT) Basic Track | This program was designed for participants who were deemed not job-ready. Education and training activities were most common, with some focus on job search. |

| Los Angeles, CA Jobs - First GAIN | Beginning in 1996, the program was mandatory for single-parent welfare recipients and applicants with no children under the age of 3. Most people started with a group job search activity (i.e., job club). Financial sanctions were regularly used. |

Appendix B

| TABLE B-1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Recipients Worked Regardless of Work Requirements | |||

| Percentage of cash assistance recipients ever employed in years 1 to 5 | |||

| Program Name | Subject to Work Requirements (Program Group) | Not Subject to Work Requirements (Control) | Impact |

| Atlanta, GA (LFA) | 83.3 | 82.9 | 0.4 |

| Atlanta, GA (HCD) | 81.2 | 82.9 | -1.7 |

| Grand Rapids, MI (LFA) | 94.7 | 91.9 | 2.9* |

| Grand Rapids, MI (HCD) | 93.6 | 91.9 | 1.7 |

| Portland, OR | 93.5 | 93.3 | 0.2 |

| Riverside, CA (LFA) | 85.7 | 80.8 | 4.9** |

| Riverside, CA (HCD) | 82.8 | 74.2 | 8.6*** |

*, **, and *** denotes statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels, respectively, with .01 being the highest level of significance.

Note: LFA = Labor Force Attachment (programs that focus primarily on job search, also known as “work first” programs); HCD = Human Capital Development (programs that also include skills training and education).

Source: Gayle Hamilton et al., “National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies: How Effective Are Different Welfare-to-Work Approaches? Five-Year Adult and Child Impacts for Eleven Programs,” Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, December 2001, Appendix Table C.5

| TABLE B-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Requirements Did Not Reduce Poverty in Most Sites | |||

| Poverty Rate | |||

| Program Name | Subject to Work Requirements (Program Group) | Not Subject to Work Requirements (Control) | Impact |

| NEWWS Study Sites | |||

| Atlanta, GA (LFA) | 85.5 | 87.1 | -1.6 |

| Atlanta, GA (HCD) | 85.1 | 87.1 | -2.0* |

| Columbus, OH (Integrated) | 79.3 | 79.3 | 0.0 |

| Columbus, OH (Traditional) | 79.0 | 79.3 | -0.3 |

| Detroit, MI | 82.9 | 84.1 | -1.2 |

| Grand Rapids, MI (LFA) | 85.3 | 86.5 | -1.2 |

| Grand Rapids, MI (HCD) | 86.2 | 86.5 | -0.3 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 92.3 | 92.8 | -0.5 |

| Portland, OR | 79.4 | 83.4 | -4.0*** |

| Riverside, CA (LFA) | 82.5 | 83.5 | -1.0 |

| Riverside, CA (HCD) | 86.2 | 86.4 | -0.2 |

| Other Study Sites | |||

| IMPACT Basic Track (IN) | 88.2 | 91.2 | -3.0 |

| Los Angeles, CA Jobs - 1st GAIN | 71.1 | 75.6 | -4.5 |

*, **, and *** denotes statistical significance at the .10, .05, and .01 levels, respectively, with .01 being the highest level of significance.

Note: Poverty status are based on a measure of income that includes earnings, cash assistance payments, and SNAP benefits. LFA = Labor Force Attachment group (programs that focus primarily on job search, also known as “work first” programs); HCD = Human Capital Development group (programs that also include skills training and education). NEWWS = National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies; GAIN = Greater Avenues for Independence; IMPACT = Indiana Manpower Placement and Comprehensive Training Basic Track. The Columbus, Ohio, integrated site featured one worker providing employment case management and eligibility determination, while the traditional site featured two workers: one completing eligibility functions and one providing employment case management.

Source: Grogger et al, “Consequences of Welfare Reform: A Research Synthesis,” Rand Corporation, July 2002, http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/resource/consequences-of-welfare-reform-a-research-synthesis, Table 8.1

End Notes

[1] I would like to acknowledge the tremendous effort Katherine Eddins, a former intern, put in to gathering and synthesizing information for this analysis.

[2] Chairman Brady Opening Statement at Markup of Bills to Improve TANF, May 11, 2016, http://waysandmeans.house.gov/chairman-brady-opening-statement-at-markup-of-bills-to-improve-tanf/.

[3] Our analysis primarily draws on 13 random assignment studies that examine the impacts of programs that focus on mandatory work or related activities and are included in a comprehensive analysis of welfare reform by Jeffrey Grogger and Lynn A. Karoly in their book, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005. A description of these studies and additional sources can be found in Appendix A.

[4] The programs cited most often are programs in Riverside, California, and Portland, Oregon, both of which we include in our analysis. These studies, like the others we examine, randomly assigned people to a “program group” that was mandated to participate in a work program or a “control group” that was offered limited employment assistance on a voluntary basis.

[5] Jeffrey Grogger et al., “Consequences of Welfare Reform: A Research Synthesis,” Rand Corporation, July 2002, http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/resource/consequences-of-welfare-reform-a-research-synthesis, Table 5.1.

[6] Labor force attachment programs focus primarily on job search and are also known as “work first” programs.

[7] Gayle Hamilton et al., “National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies: How Effective Are Different Welfare-to-Work Approaches? Five-Year Adult and Child Impacts for Eleven Programs.” Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, December 2001, http://www.mdrc.org/publication/how-effective-are-different-welfare-work-approaches, Appendix Table C-1.

[8] Ibid. Appendix Table C.5.

[9] Gaye Hamilton et al., December 2001, Table C.6.

[10] Chi-Fang Wu, Daniel R. Meyer, and Maria Cancian, “Standing Still or Moving Up? Evidence from Wisconsin on the Long-Term Employment and Earnings of TANF Participants,” Social Work Research, February, 2008, Vol. 32, No. 2.

[11] Lisa Thiebaud Nicoli, “Climbing the Ladder? Patterns in Employment and Earnings After Leaving Welfare,” Family Welfare Research & Training Group, University of Maryland, October 2015, http://www.familywelfare.umaryland.edu/reports1/trajectories.pdf.

[12] For example, see: Pamela L. Loprest and Elaine Maag, “Disabilities among TANF Recipients: Evidence from the NHIS,” Urban Institute, May 2009, http://www.urban.org/research/publication/disabilities-among-tanf-recipients-evidence-nhis. (This study also includes data on SNAP recipients.)

[13] Dan Bloom, Cynthia Miller, and Gilda Azurdia, “Results from the Personal Roads to Individual Development and Employment (PRIDE) Program in New York City,” mrdc, July 2007,

[14] Stephen Freedman et al., “National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies: Two-year Impacts for Eleven Programs,” Manpower Development Research Corporation, June 2000, http://www.mdrc.org/publication/evaluating-alternative-welfare-work-approaches, Table A-2.

[15] Joseph Hotz, Guido Imbens, and Jacob Klerman, “The Long-Term Gains from GAIN: A Re-Analysis of the Impacts of the California GAIN Program,” November 2000, http://www.nber.org/papers/w8007.pdf?new_window=1.

[16] Andrew Dyke et al., “The Effects of Welfare‐to‐Work Program Activities on Labor Market Outcomes,” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol 24, No. 3, February 2006: 567-607, http://www.ukcpr.org/sites/www.ukcpr.org/files/files/newsletters/Newsletter-Vol4_2_Article4.pdf.

[17] Carol Clymer et al., “Tuning In to Local Labor Markets: Findings From the Sectoral Employment Impact Study,” Public/Private Ventures, July 1, 2010, http://ppv.issuelab.org/resource/tuning_in_to_local_labor_markets_findings_from_the_sectoral_employment_impact_study.

[18] Anne Roder and Mark Elliott, “Sustained Gains: Year–Up’s Continued Impact on Young Adults’ Earnings,” Economic Mobility Corporation, May 2014, http://economicmobilitycorp.org/uploads/sustained-gains-economic-mobility-corp.pdf.

[19] Unless otherwise noted all data in this section are from Freedman et al.

[20] Grogger et al., “Consequences of Welfare Reform: A Research Synthesis,” Rand Corporation, July 2002,http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/resource/consequences-of-welfare-reform-a-research-synthesis, Table 8.1.

[21] Thomas Brock et al., “Welfare Reform in Cleveland Implementation, Effects, and Experiences of Poor Families and Neighborhoods,” Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, September 2002, http://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_603.pdf.

[22]Robert G. Wood and Anu Rangarajan,“What’s Happening to TANF Leavers Who Are Not Employed?” Mathematica Policy Research, October 2003, http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/media/publications/PDFs/tanfleave.pdf.

[23] The Jobs-Plus demonstration project was implemented in six sites. Four of those sites — Dayton, Ohio; Los Angeles, California; St. Paul, Minnesota, and Seattle, Washington — built substantial programs. As would be expected, the program impacts were substantially better in the sites where the program was well-implemented.

[24] Howard Bloom, James. A. Riccio, and Nandita Verma, “Promoting Work in Public Housing: The Effectiveness of Jobs-Plus,” Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, March 2005.

[25] James A. Riccio, “Sustained Earnings Gains for Residents in a Public Housing Jobs Program: Seven-Year Findings from the Jobs-Plus Demonstration,” Manpower Demonstration Research Corporation, January 2010, http://www.mdrc.org/publication/sustained-earnings-gains-residents-public-housing-jobs-program.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Jeffrey Grogger and Lynn A. Karoly, Welfare Reform: Effects of a Decade of Change, Harvard University Press, 2005 and the initial report on which their book is based, Jeffrey Grogger, Lynn A. Karoly and Jacob Klerman. “Consequences of Welfare Reform: A Research Synthesis.” Rand Corporation, July 2002, http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/resource/consequences-of-welfare-reform-a-research-synthesis.

[28] Our analysis does not include studies that examined the impact of a “bundle” of reforms, including such policies as cash work incentives and time limits along with work requirements, because it isn’t possible to isolate the impacts of work requirements in those studies. Grogger and Karoly include these studies in their analysis but review them separately from those that focus only on mandatory work or related activities.

More from the Authors