Working childless adults[2] are the lone group that the federal tax code taxes into or deeper into poverty, largely because they are also the only group largely excluded from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). For low-income working families with children, the EITC encourages and rewards work and offsets federal payroll and income taxes. The EITC for childless adults, by contrast, is so small that it effectively does none of those things. Today, the federal tax code taxes about 7.5 million childless adults aged 21 through 66 into or deeper into poverty.

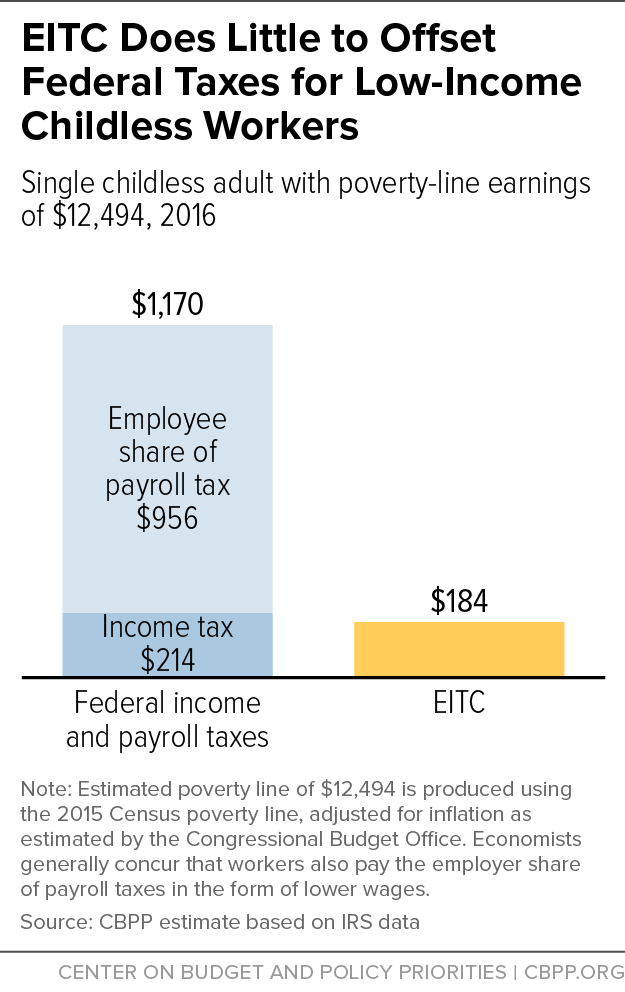

Consider, for example, a 21-year-old just starting out in the workforce and making poverty-level wages of about $12,500 for manual labor. This worker has $956 in payroll taxes deducted from his paycheck and pays $214 in federal income taxes. Because the worker receives zero EITC (childless workers under age 25 are ineligible), he is taxed $1,170 into poverty — that is, the taxes leave him $1,170 below the poverty line. A 30-year-old woman making the same low wages in a retail store owes the same taxes, and she does qualify for an EITC (she is age 25 or older), but her credit is only $184 — with the result that she, too, is taxed into poverty.

Fortunately, leading policymakers from both parties recognize this problem. President Obama and House Speaker Paul Ryan have put forth nearly identical proposals to lower the eligibility age for the childless workers’ EITC to 21 and to raise the maximum credit to roughly $1,000. These changes would make significant progress toward meeting the core principle that no American worker should be taxed into poverty, though they do not get all of the way to that goal. Senate Finance Committee member Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and House Ways and Means Committee member Richard Neal (D-MA) have introduced more robust proposals that would essentially ensure that the federal tax code doesn’t tax childless wage-earners aged 21 through 64 into poverty.

Providing a more adequate EITC to low-income childless workers and lowering the eligibility age would have important benefits beyond raising these workers’ incomes and helping offset their federal taxes. Some leading experts believe that an expanded EITC for these workers would also help address some of the challenges that less-educated young people (particularly young African American men) face including low and falling labor-force participation rates, low marriage rates, and high incarceration rates.

These proposals would reward the hard work of a broad swath of people in every state — young and older, male and female, and across all races — who do important low-paid jobs in hospitals, schools, office buildings, and construction sites. (See Table 3.) Of the 13 million workers who would benefit from the Obama and Ryan proposals, roughly 35 percent are at least 45 years old, and 1.5 million or more are non-custodial parents.[3] About 6 million are women.[4] Some 630,000 are veterans or military service members. Workers in a diverse range of occupations and demographic groups would benefit (see Table 2). Table 1 shows the state-by-state impact of the proposal.

An additional 3 million workers — 16.2 million overall — would benefit from the Brown-Neal proposal. Roughly 32 percent of the workers who would benefit are at least 45 years old, and 7.2 million are women. Similar to the proposals from Obama and Ryan, workers in a diverse range of occupations and demographic groups would benefit.

Since enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, federal income tax parameters have generally been designed to ensure that federal income and payroll taxes don’t tax people into or deeper into poverty. The glaring exception to this principle is childless workers. Roughly 7.5 million childless workers aged 21 through 66 are taxed into or deeper into poverty. (An additional 1.6 million childless workers aged 18 through 20 and 143,000 over 66 face a similar situation.)

The standard deduction and personal exemption levels are set at levels to ensure that families with children (as well as low-income seniors who receive most of their income from Social Security) don’t start owing federal income tax until their earnings exceed the poverty line. In addition, working-poor families with children can qualify for an EITC and Child Tax Credit that offset their substantial payroll tax liabilities and supplement their earnings.

Single childless adults, in contrast, begin owing federal income taxes when their earnings reach just $10,350,[5] some $2,000 below the poverty line for a single adult.

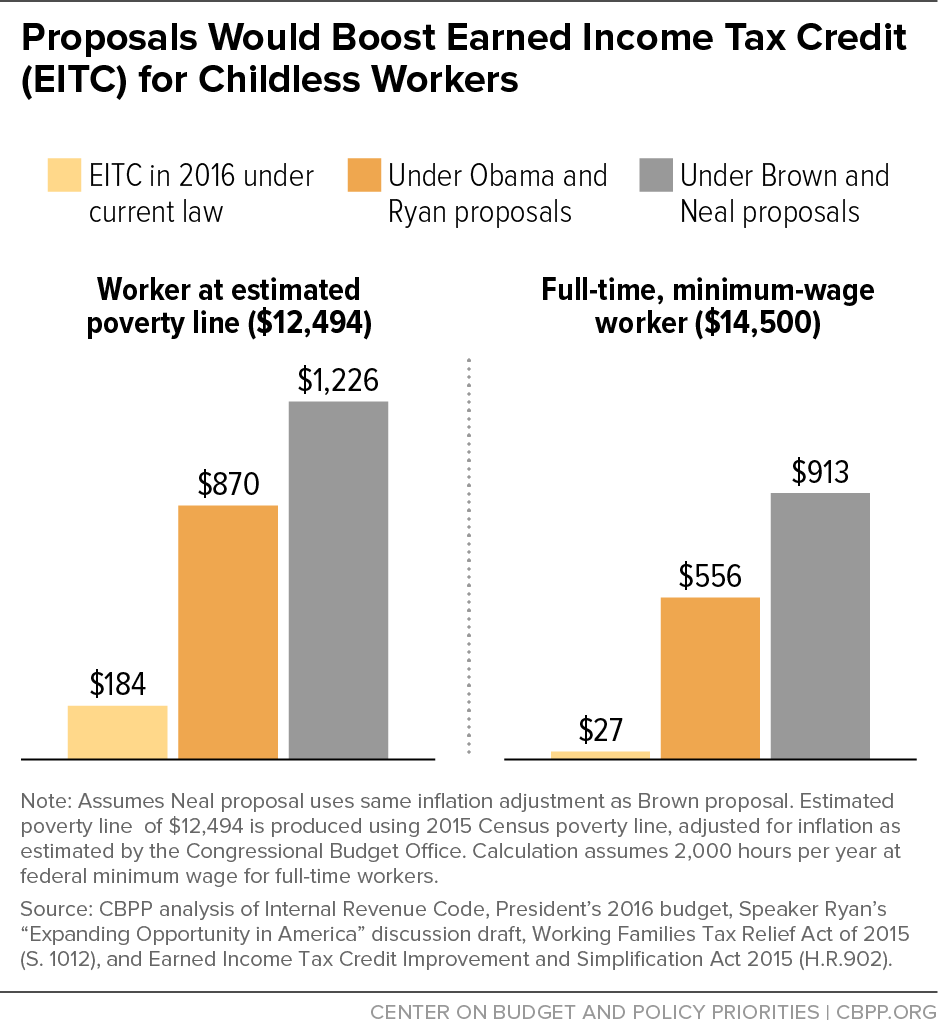

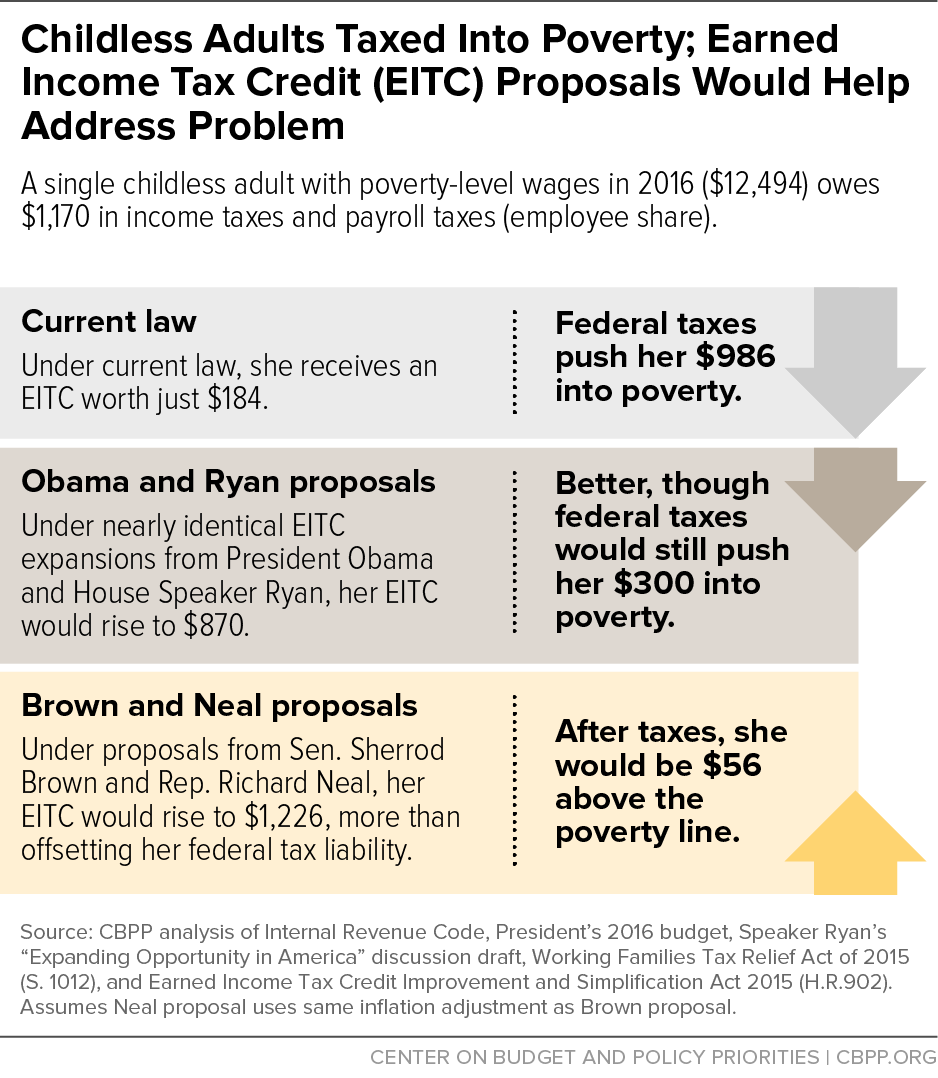

Consider a childless worker with poverty-line earnings of $12,494 in 2016. The worker owes $214 in income taxes and $956 in the employee share of payroll taxes. (The employer pays another $956 in payroll taxes, the burden of which falls on workers in the form of lower wages, most economists agree.) Her combined income and payroll tax liability is therefore $1,170, counting only the employee share of the payroll tax. Yet she receives an EITC of just $184, less than her income tax bill alone. (See Figure 1.) The combined effect of the income tax (including the EITC) and the employee share of payroll taxes pushes her $986 below the poverty line.

CBPP analysis of data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey finds that in 2014, federal income and payroll taxes pushed about 7.5 million childless workers aged 21 to 66 into, or deeper into, poverty.[6]

The main reason why so many childless adults are taxed into poverty is that many are ineligible for the EITC, while others receive a credit too small to offset their income tax liability, let alone their much larger payroll tax obligations.

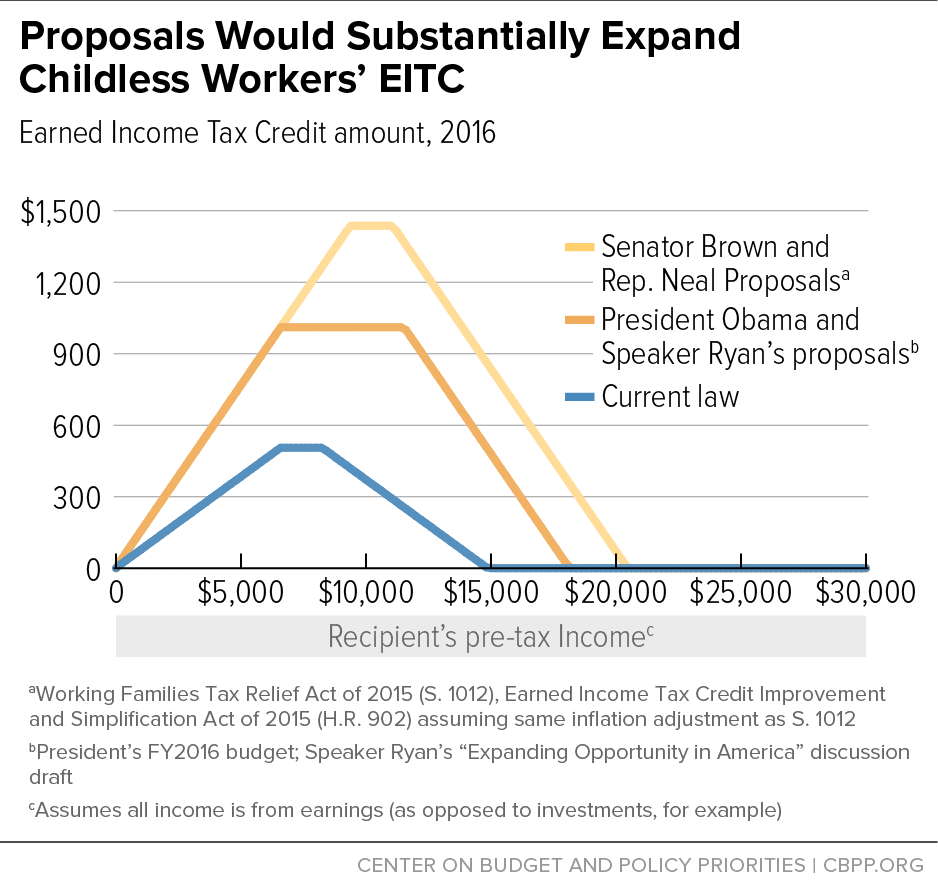

The EITC entirely misses low-income childless workers under age 25; they, as well as workers over 64, are ineligible. For those who are eligible, the credit is very small. It phases in at a rate of 7.65 percent — a worker receives an EITC equal to 7.65 cents for each dollar of earnings until the worker’s earnings reach about $6,610 in 2016, at which point the credit equals $506. Single workers with earnings between $6,610 and $8,270 receive this $506 maximum credit amount. The credit then begins phasing out as the worker’s earnings exceed $8,270, which is just 66 percent of the poverty line for a single childless worker (and equals less than 60 percent of earnings from full-time year-round federal minimum-wage work). The credit disappears completely when earnings reach $14,880.

The average credit for eligible workers was about $280 in 2013, the latest year for which data are available. This is less than one-tenth the average $3,100 EITC for tax filers with children in 2013.

A childless adult working full time at the minimum wage (and earning $14,500) will incur a federal income and payroll tax liability of $1,497 in 2016 — a substantial tax burden for someone with income this low — after receiving an EITC of just $27.

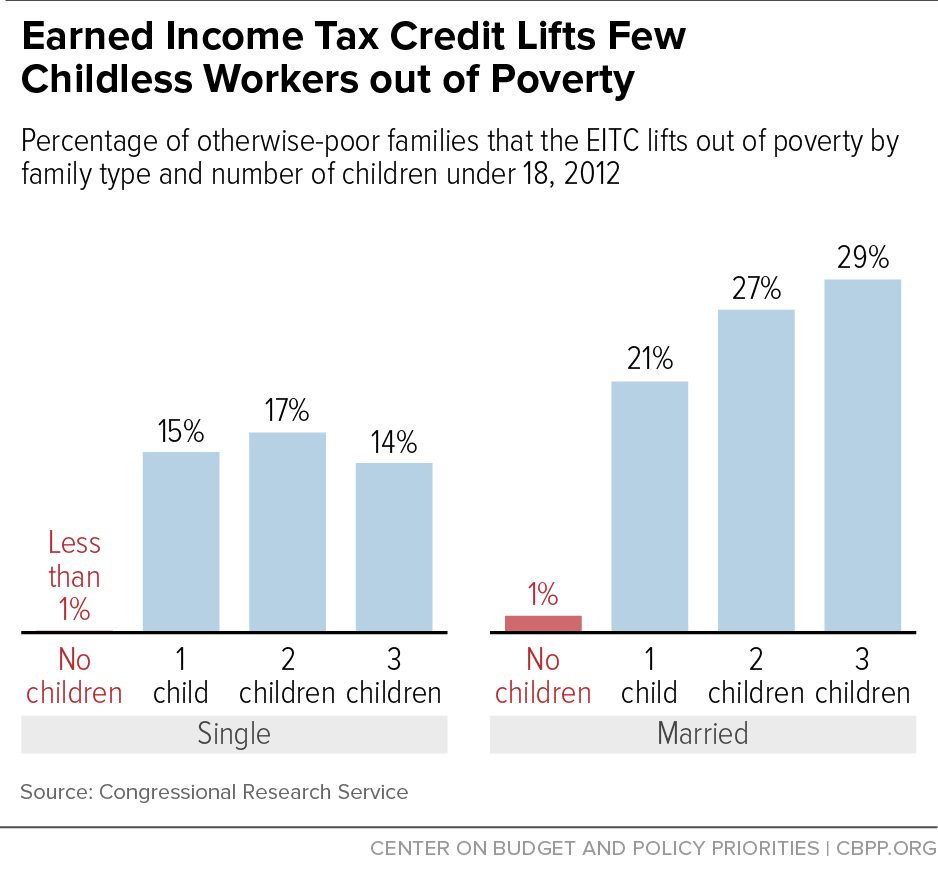

In large part due to its meager size for childless workers, the EITC does far less to lift childless families out of poverty than it does with respect to families with children. The EITC lifts about 15 percent of otherwise-poor families with children out of poverty, according to the Congressional Research Service. It lifts fewer than 1 percent of households without children out of poverty.[7] (See Figure 2.)

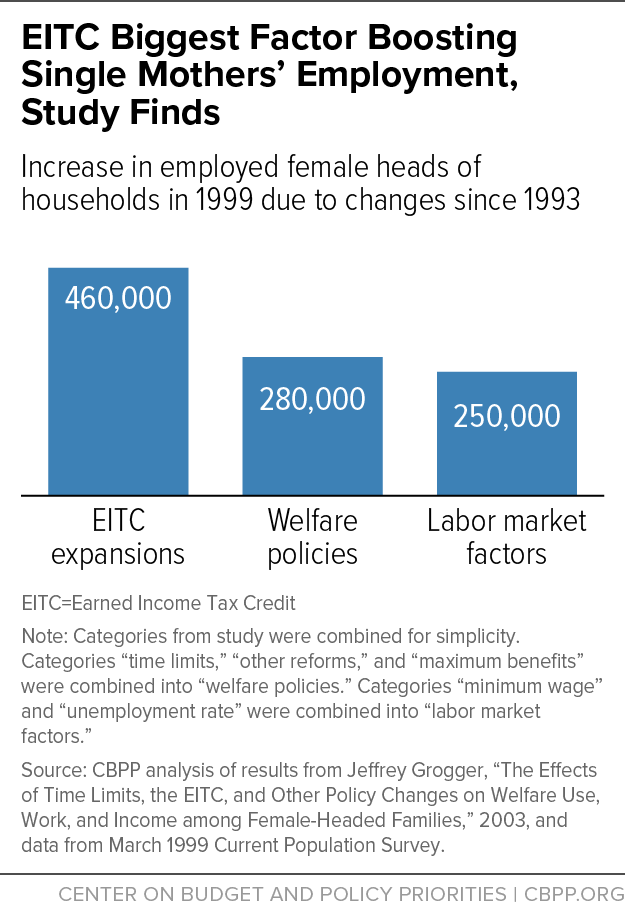

The EITC is designed to encourage and reward work, and it does so very effectively, particularly for families with children. An extensive body of research shows that it induces many people who aren’t working to take a job. It is thus a quintessential welfare-reform measure. In fact, one highly regarded study found that EITC expansions in the 1990s did more to increase employment among single mothers than the 1996 welfare law. (See Figure 3.)

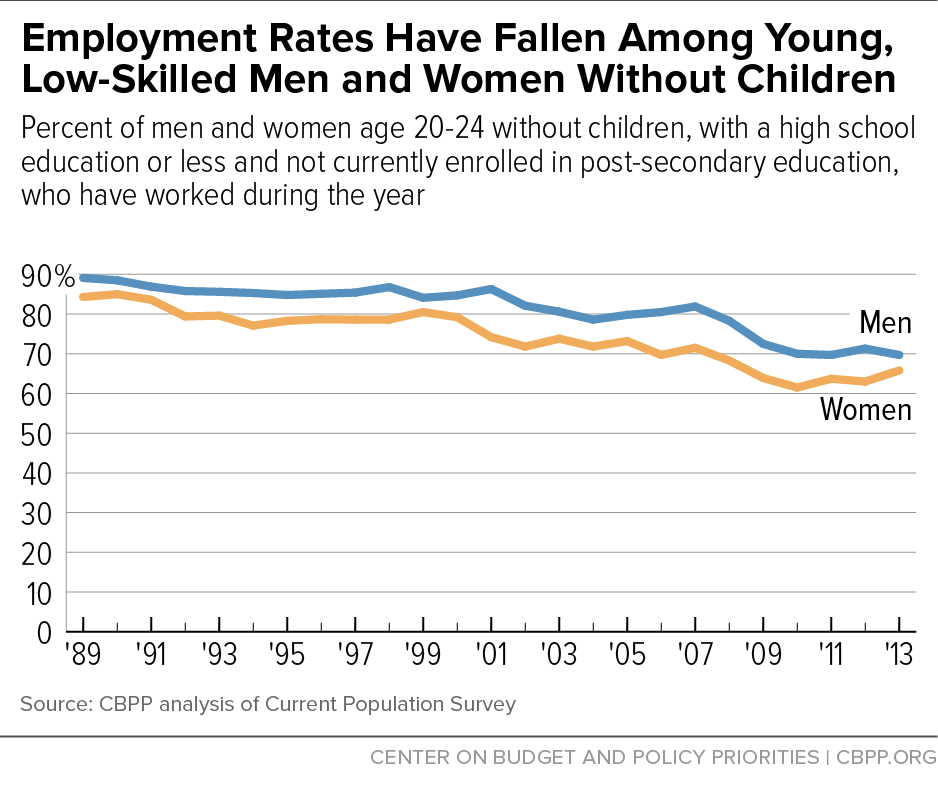

Yet this proven, pro-work instrument largely leaves out an important group. Labor-force participation has fallen among less-educated young adults who aren’t raising children, as Figure 4 shows, making them a prime candidate for a more adequate EITC.

Policymakers from both parties increasingly recognize the problems of taxing childless adults into poverty and not extending to them the robust work incentives the EITC provides for parents raising children. President Obama, House Speaker Ryan, Senator Sherrod Brown, and Rep. Richard Neal have advanced proposals to address this. Their plans share several common elements:

-

Lowering the eligibility age. Currently, workers under age 25 are ineligible for the childless workers’ EITC. All of these proposals make workers aged 21-24 eligible if they otherwise qualify.[8]

-

Increasing the phase-in rate. Under current rules, the EITC for childless workers phases in at a rate of 7.65 percent: a worker receives an EITC equal to 7.65 cents for each dollar of a worker’s first $6,610 in earnings (in 2016).

The Obama, Ryan, Brown, and Neal proposals raise the credit’s phase-in rate (as well as its phase-out rate at somewhat higher incomes) to 15.3 percent, equal to the combined employer and employee payroll tax rate.

-

Boosting the maximum tax credit. The maximum EITC for childless adults today is roughly $500. The Obama and Ryan proposals raise that to about $1,000 by increasing the credit’s phase-in rate. The Brown and Neal proposals raise the maximum EITC to roughly $1,400 by increasing both the phase-in rate and the income level at which the phase-in ends, from $6,610 today to $9,390 in 2016.

-

Modestly increasing the income levels at which the EITC phases down and then out: The current EITC for single childless adults phases out entirely at income of $14,880. Thus, a single childless adult working full time at the federal minimum wage receives hardly any EITC. All of the proposals would raise the income levels at which the EITC begins to phase out and the levels at which it disappears completely (see Figure 5).

Figure 6 focuses on two examples: a worker with poverty-level wages and one who works full time at the minimum wage. Current law largely excludes both workers from the EITC; the various proposals would deliver a tangible EITC to both.

The Obama and Ryan proposals would reduce the number of childless workers taxed into or deeper into poverty by about 5.8 million.[9] Under the Brown-Neal proposal, essentially no eligible childless wage-earners aged 21 through 64 would be taxed into or deeper into poverty by federal income and payroll taxes. [10]

We estimate that the Obama and Ryan proposals would prevent about 600,000 childless workers from being taxed into poverty and 5.2 million more workers from being taxed deeper into poverty. The Brown-Neal proposal would prevent about 800,000 childless workers from being taxed into poverty and 6.0 million more from being taxed deeper into poverty.[11]

These figures do not take state and local income taxes into account, which can tax some workers back into poverty. States and localities can address such issues, with state EITCs being a prime way of doing so. Some 26 states and the District of Columbia now have state EITCs.[12]

Providing a more adequate EITC to low-income childless workers and lowering the eligibility age, as these proposals would do, could have important benefits beyond raising these workers’ after-tax incomes and alleviating their poverty. A number of leading experts believe that an expanded EITC for these workers also would help address some of the challenges that less-educated young people (particularly young African American men) face, including low and falling labor-force participation rates, low marriage rates, and high incarceration rates.

For example, John Karl Scholz, an economist and former Treasury official who is one of the nation’s foremost authorities on the EITC, has strongly recommended a more ample EITC for childless workers as a way to raise their employment rate, explaining: “increasing the return to work for childless workers will lower unemployment rates and achieve the dual social benefits of reducing incarceration rates and increasing marriage rates.”[13]

Likewise, Ron Haskins, co-director of the Brookings Institution’s Center on Children and Families and a key architect of the 1996 welfare law (as the senior Republican staff member of the House Ways and Means Committee, which was responsible for the legislation), argues that an expanded EITC for childless workers would:

provide the very thing that most analysts agree is most needed — namely, work incentive … [and] the young man’s prospects in the marriage market would receive a nice boost. Studies show clearly that married young males are healthier, happier, less likely to commit crimes and less likely to abuse drugs than single males. Thus, to the extent that additional income increases marriage rates, the new EITC would produce fringe benefits beyond mere economic outcomes.[14]

By raising low-income workers’ after-tax incomes, the EITC increases the rewards of low-wage work. Although little empirical literature exists on the impact of the childless workers’ EITC on employment rates, careful econometric studies show that the expansions in the EITC for families with children during the 1990s raised employment rates markedly among low-skilled single mothers. And as noted above, a highly regarded study by University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger found that the EITC expansions during this period did more to increase employment among single mothers than the 1996 welfare law.[15] Many researchers believe these results are robust enough to conclude that substantially expanding the childless workers’ credit would be likely to increase labor-force participation among low-skilled childless workers.[16]

Young men’s and women’s employment rates (the percentage who are working or actively looking for work) have been declining for over two decades, particularly for men and women with no education beyond high school. Between 1989 and 2014, the employment rate of childless men aged 20 to 24 with a high school education or less fell from 89 percent to 71 percent. The employment rate for women in this group also fell sharply, from 84 percent to 67 percent (see Figure 4).

Real incomes, as well, have fallen for less educated men and women. Between 1991 and 2014, median earnings for full-time year-round workers over age 24 who have less than a high-school diploma fell by 9 percent, from $27,500 to $25,000 (in 2014 dollars).[17]

Raising the rewards of work for childless workers may also increase their marriage rates, several analysts have observed.[18] Marriage rates have fallen almost 30 percentage points for men aged 30 to 50 in the bottom 35 percent of the annual earnings distribution since the 1970s.[19] In 1987, William Julius Wilson noted the correlation between falling real wages and declining marriage rates in low-income communities,[20] arguing that low employment rates and falling wages reduced the “marriageability” of young men, resulting in an increase in the number of female-headed households. More recently, a 2009 study found that three-quarters of low-income, unwed survey respondents cited financial concerns as an obstacle to marriage.[21]

Marriage can benefit both children and their parents in several ways. Two-parent households have lower poverty rates than single-parent households, in part because they can pool their incomes and resources. Marriage can also promote stability, improving health and lowering stress among parents and children. A number of studies find that children living with two parents (excluding high-conflict marriages) tend to fare better than other children on educational, social, and health outcomes, even after controlling for parental characteristics such as age, income, and education.[22] By rewarding employment among childless individuals (particularly young workers), a more ample childless EITC can lead more of them to work or to work more, thereby boosting not only their current wages but also their employment experience and hence their long-term earning potential. Greater earnings and higher employment can, in turn, improve the marriage prospects of young, low-income men.

The decline in employment among young men is even greater than the employment figures cited above suggest, since those figures do not include people who are incarcerated. Young men have disproportionately high incarceration rates, and taking incarceration into account significantly reduces the employment rate for young adults, particularly men of color. One study found that roughly 40 percent of black male high school dropouts under age 35 were employed in 2000, but that the share drops to 25 percent when one includes incarcerated black men.[23] Some 17 percent of men between aged 20 and 24 were arrested in 2010, according to a recent Justice Department report. (Although not everyone who is arrested is imprisoned, incarceration rates are still high: one in 36 adults were under some form of correctional control in 2014.)[24] Upon release, these individuals typically face inhospitable labor markets.[25]

Some evidence suggests that by boosting the incomes of low-wage workers who participate in the above-ground economy, an expanded EITC may help reduce crime rates. Although the relationship between wage rates and crime is difficult to disentangle (due to the many factors that affect crime rates), researchers have found that lower wages for less-educated people are associated with higher crime rates.[26] Based on this relationship, several leading analysts such as Harry Holzer of the Urban Institute and Georgetown University and John Karl Scholz have argued that, by increasing the employment levels and income of low-skilled individuals, an expanded childless workers’ EITC would likely reduce crime rates among young, disadvantaged men.[27]

Expanding EITC for Childless Workers Would Also Help Children

Expanding the EITC for childless adults would help not only the adults who receive the credits, but also children and their communities for at least three reasons:

- Many childless workers are non-custodial parents with financial and parenting obligations to their children. The President’s proposal would benefit about 1.5 million noncustodial parents, the Treasury Department estimates.a By helping them succeed in the labor market, a larger EITC can also help them meet these other responsibilities, including serving as a role model to their children.

- Many childless workers are future parents. The Obama, Ryan, Brown, and Neal proposals extend the EITC to younger workers (those aged 21-24), many of them future parents. The better a foothold that young workers gain in the labor market, the more likely they will succeed over time and provide for their children when they start families.

- Childless workers are part of the community. Children’s success also depends on their extended families and communities. A stronger EITC for childless adults can support a child’s siblings, uncles, aunts, or grandparents who may be considered “childless” for tax purposes even if they live in the same home as their younger relatives. In addition, as noted, a stronger EITC for young childless workers could strengthen their labor-force participation and marriage prospects and reduce crime, which improve the communities in which children are growing up.

a Executive Office of the President and U.S. Treasury Department, “The President’s Proposal to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit,” March 3, 2014, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/eitc_report.pdf.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Workers helped under Obama, Ryana plans |

Workers helped under Brown, Neal plans |

|---|

| United States |

13,000,000 |

16,200,000 |

| Alabama |

194,000 |

235,000 |

| Alaska |

38,000 |

48,000 |

| Arizona |

230,000 |

306,000 |

| Arkansas |

118,000 |

135,000 |

| California |

1,495,000 |

1,877,000 |

| Colorado |

202,000 |

270,000 |

| Connecticut |

140,000 |

199,000 |

| Delaware |

35,000 |

42,000 |

| District of Columbia |

24,000 |

29,000 |

| Florida |

994,000 |

1,246,000 |

| Georgia |

468,000 |

621,000 |

| Hawaii |

58,000 |

71,000 |

| Idaho |

64,000 |

76,000 |

| Illinois |

525,000 |

662,000 |

| Indiana |

275,000 |

324,000 |

| Iowa |

120,000 |

156,000 |

| Kansas |

115,000 |

130,000 |

| Kentucky |

181,000 |

225,000 |

| Louisiana |

185,000 |

223,000 |

| Maine |

62,000 |

72,000 |

| Maryland |

206,000 |

244,000 |

| Massachusetts |

266,000 |

299,000 |

| Michigan |

459,000 |

541,000 |

| Minnesota |

220,000 |

318,000 |

| Mississippi |

125,000 |

143,000 |

| Missouri |

252,000 |

291,000 |

| Montana |

51,000 |

71,000 |

| Nebraska |

76,000 |

95,000 |

| Nevada |

107,000 |

133,000 |

| New Hampshire |

58,000 |

74,000 |

| New Jersey |

343,000 |

425,000 |

| New Mexico |

90,000 |

104,000 |

| New York |

871,000 |

1,102,000 |

| North Carolina |

369,000 |

450,000 |

| North Dakota |

29,000 |

36,000 |

| Ohio |

502,000 |

608,000 |

| Oklahoma |

145,000 |

172,000 |

| Oregon |

159,000 |

195,000 |

| Pennsylvania |

554,000 |

659,000 |

| Rhode Island |

46,000 |

58,000 |

| South Carolina |

196,000 |

237,000 |

| South Dakota |

37,000 |

47,000 |

| Tennessee |

287,000 |

366,000 |

| Texas |

994,000 |

1,328,000 |

| Utah |

99,000 |

133,000 |

| Vermont |

32,000 |

39,000 |

| Virginia |

304,000 |

353,000 |

| Washington |

254,000 |

321,000 |

| West Virginia |

81,000 |

94,000 |

| Wisconsin |

246,000 |

297,000 |

| Wyoming |

24,000 |

29,000 |

| Appendix Table 2 |

|---|

| |

Workers helped under Obama, Ryana plans |

Workers helped under Brown, Neal plans |

|---|

| Veterans and military members |

630,000 |

716,000 |

| Workers with disabilitiesb |

908,000 |

971,000 |

| Millennials (ages 18–34) |

7,072,000 |

8,974,000 |

| Black (non-Latino) |

2,119,000 |

2,611,000 |

| Latinos |

2,914,000 |

3,851,000 |

| White (non-Latino) |

6,926,000 |

8,393,000 |

| Asian Americans |

670,000 |

812,000 |

| American Indians and Alaskan Natives |

357,000 |

440,000 |

| Women |

6,017,000 |

7,249,000 |

| Men |

6,987,000 |

8,932,000 |

| Rural |

1,900,000 |

2,239,000 |

| Under 25 |

3,686,000 |

4,433,000 |

| 25-34 |

3,386,000 |

4,540,000 |

| 35-44 |

1,444,000 |

1,969,000 |

| 45-54 |

1,925,000 |

2,478,000 |

| 55+ |

2,563,000 |

2,761,000 |

| Appendix Table 3 |

|---|

| |

Workers helped by Obama, Ryana plans |

Workers helped by Brown, Neal plans |

|---|

| Management, business, financial |

631,000 |

740,000 |

| Professional, related occupations |

1,329,000 |

1,698,000 |

| Service occupations |

3,814,000 |

4,679,000 |

| Sales and related occupations |

1,682,000 |

2,059,000 |

| Office and administrative support |

1,354,000 |

1,778,000 |

| Farming, fishing, forestry |

165,000 |

222,000 |

| Construction and extraction |

723,000 |

996,000 |

| Installation, maintenance, repair |

307,000 |

413,000 |

| Production occupations |

664,000 |

934,000 |

| Transportation, material moving |

1,106,000 |

1,347,000 |