Over the past few years, states have faced large budgets gaps caused by a dramatic decline in revenue collections since the start of the recession. One contributor to this fiscal crisis in many states has been a relatively new corporate tax break — one that in most states never even received a vote in the state legislature but nonetheless is costing states hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

The federal government created this tax break, known as the “domestic production deduction,” in 2004. Since most states base their own tax codes on the federal tax code, the tax break was carried over into many states without specific legislative scrutiny or a vote. Now it is costing not only the federal government but also 25 states a large amount of money. By 2014, it will cost these states over $600 million per year.

The deduction — enacted as Section 199 of the federal Internal Revenue Code — allows companies to claim a tax deduction based on profits from “qualified production activities,” a sweeping category that goes well beyond manufacturing to include such diverse activities as food production, filmmaking, and utilities — a substantial share of states’ corporate income tax base.

The revenue loss to states that still allow the deduction has increased steeply over the past few years. Initially, the cost was relatively modest because the deduction was limited to 3 percent of qualifying income. The percentage rate rose to 6 percent in 2007, and the final increase to 9 percent took effect in the 2010 tax year. Federal estimates suggest that allowing this deduction will reduce the revenue yield of corporate taxes by roughly 2.8 percent in 2014 and also reduce individual income taxes somewhat.

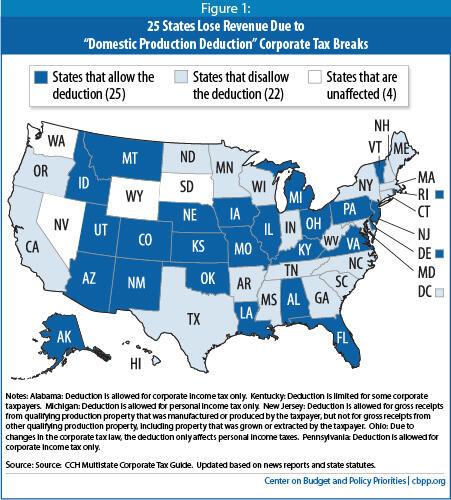

States are not required to allow this deduction. Since 2008, Connecticut, New York, Wisconsin, and the District of Columbia have joined 18 other states in disallowing the deduction, thereby reducing their budget shortfalls and benefitting their states’ economies. But another 25 states continue to permit it. (Four states lack both personal and corporate income taxes and so are unaffected.) If they continue to do so, a conservative estimate suggests the tax break will cost those states $635 million in 2014. (These estimates are based on current levels of corporate and personal income tax revenue.)

There is no good reason why states should accept such revenue losses.

- The deduction is unlikely to protect or create jobs within the state, because multi-state corporations can claim the deduction for out-of-state “production activity” just as they can for in-state activity.

- The deduction provides little or no help to financially ailing businesses, since only profitable firms have taxable income for it to offset.

Table 1

Extent to Which Different Industries Claim Domestic Production

Deduction Against Corporate Income Tax |

| Industry Grouping | Total Number of Returns | Total Taxable Income

($ millions) | Amount of Deduction Claimed

($ millions) | Share of Deduction Claimed | Estimate of Qualifying Income as a Share of Taxable Income |

| Manufacturing | 259,859 | 383,494 | 8,930 | 62.8% | 38.8% |

| Information | 116,514 | 63,265 | 2,447 | 17.2% | 64.5% |

| Mining | 38,348 | 24,126 | 421 | 3.0% | 29.1% |

| Construction | 742,436 | 9,786 | 388 | 2.7% | 66.1% |

| Utilities | 6,072 | 16,760 | 541 | 3.8% | 53.8% |

| Wholesale Trade | 375,922 | 51,992 | 594 | 4.2% | 19.0% |

| Professional and Technical Services | 864,803 | 26,077 | 318 | 2.2% | 20.3% |

| Retail Trade | 596,710 | 76,589 | 194 | 1.4% | 4.2% |

| Finance and Insurance | 239,864 | 132,294 | 81 | 0.6% | 1.0% |

| Management of Companies | 47,729 | 52,518 | 45 | 0.3% | 1.4% |

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 138,792 | 2,237 | 114 | 0.8% | 85.1% |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 297,986 | 11,868 | 61 | 0.4% | 8.6% |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 647,037 | 6,355 | 22 | 0.2% | 5.8% |

| Administrative, Support, and Waste Services | 273,900 | 7,908 | 21 | 0.1% | 4.4% |

| Other Services | 375,059 | 1,891 | 12 | 0.1% | 10.3% |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 195,594 | 12,093 | 9 | 0.1% | 1.2% |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 122,225 | 1,219 | 5 | 0.0% | 6.7% |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 429,339 | 10,387 | 12 | 0.1% | 1.9% |

| Educational Services | 55,309 | 3,988 | 14 | 0.1% | 6.0% |

| Other Industries (Not Allocable) | 300 | 4 | 0 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Total | 5,824,545 | 894,850 | 14,228 | 100.0% | 26.5% |

*Figures are based on tax year 2009 data. The deduction was worth 6% of qualifying income in 2009. Had businesses been able to claim the full 9% in 2009, the amount of the deduction claimed would have been 50% higher.

Source: IRS Statistics of Income Data. |

- The deduction is heavily slanted towards large corporations. In 2009, 93 percent of the deduction taken under the corporate income tax was claimed by the 0.5 percent of firms with over $100 million apiece in assets.[1] Many of these large firms are multi-state corporations and may invest little or nothing in the state granting the tax break.

- Most importantly, given the large cuts most states have had to make in education, healthcare, and many other critical services, it makes little sense for them to provide such a large tax break. Maintaining the tax break would mean states would have to cut more elsewhere, and the jobs lost due to such cuts would almost certainly exceed any jobs created by maintaining this costly and inefficient deduction.

Decoupling from the domestic production deduction, as 22 states have already shown, is simple to enact and easy to administer.[2] It can be done by adding a single sentence to state tax law requiring corporations to add back the deducted amount to their taxable income and a single line to state tax forms.

The domestic production deduction allows businesses to deduct — and hence pay no taxes on — a portion of their profits attributable to a broad range of “qualified production activities.”[3] Three percent of this income was deductible in 2005 and 2006; 6 percent was deductible in 2007, 2008, and 2009; and 9 percent is deductible in 2010 and years thereafter.

The deduction is broad in its scope and therefore costly in its fiscal impact. Although the deduction is often described as a tax break for manufacturing activities, it is actually much less targeted. In fact, deductible income can be any profits (that is, receipts minus costs) that a business can attribute to a broad range of activities, including:

- food processing (but not retail food sales),

- software development,

- filmmaking,

- mining and oil extraction,

- publishing,

- electricity/natural gas production, and

- construction.

Even firms outside these industries benefit. Virtually every sector of the economy has seen its taxes cut by this tax break, including firms whose primary business is retail sales, financial services, and entertainment.[4] Overall, business tax returns for 2009 claimed that about 27 percent of all corporate taxable income qualified for the deduction.[5] (See Table 1.)

The domestic production deduction affects states because states generally conform their tax codes to the federal Internal Revenue Code. For personal income taxes, most states use “taxable income” or “adjusted gross income” as calculated for federal tax purposes as the starting point for their own income tax calculations. Similarly, most states begin their corporate income tax calculations with federal “taxable income” from the federal corporate tax form. Therefore, when federal legislation narrows the definition of taxable or adjusted gross income, taxpayers report less income and states typically see a decline in revenue.

To understand how this deduction affects state income taxes, consider a hypothetical corporation with $10 million in “domestic production” income, located in a state with a 5 percent corporate income tax rate. From 2010 onward, 9 percent of that income is deductible — meaning the corporation gets to claim $900,000 of profits as tax-free income. At a tax rate of 5 percent, the corporation gets a state income tax break worth $45,000.

Table 2

Approximate Revenue Loss in States That Still Allow the Domestic Production Deduction |

| State | Annual Revenue

Loss in 2014

(in millions of dollars) | State | Annual Revenue

Loss in 2014

(in millions of dollars) |

| Alabama | 11 | Missouri | 26 |

| Alaska | 19 | Montana | 7 |

| Arizona | 29 | Nebraska | 13 |

| Colorado | 31 | New Jersey | N/A |

| Delaware | 14 | New Mexico | 8 |

| Florida | 57 | Ohio | 32 |

| Idaho | 10 | Oklahoma | 22 |

| Illinois | 139 | Pennsylvania | 52 |

| Iowa | 21 | Rhode Island | 7 |

| Kansas | 16 | Utah | 16 |

| Kentucky | 5 | Vermont | 5 |

| Louisiana | 15 | Virginia | 59 |

| Michigan | 23 | TOTAL | 635 |

Not surprisingly, such a broadly available tax break carries a heavy fiscal cost. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), which estimates federal revenue impacts for Congress, projects that the Section 199 provision will cost the federal government $10.3 billion in 2014 — about 2.8 percent of projected federal revenue from corporate income taxes plus another 0.3 percent of projected revenue from personal income taxes.[6]

States face losses of comparable magnitude. In fiscal year 2014 it is likely to cost conforming states $635 million a year.[7] State-by-state amounts are shown in Table 2.[8]

States are not required to accept revenue losses from the domestic production deduction. As of January 2013, 21 states plus the District of Columbia have “decoupled,” disallowing the deduction on state tax returns. Connecticut and Wisconsin decoupled in 2009; New York and the District of Columbia decoupled in 2008. Arkansas, California, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia are also disallowing the deduction.[9]

Most of those states still conform to most other provisions of federal tax law, including other changes adopted by Congress at the same time that Section 199 was enacted. For example, states generally also conformed to the 2004 elimination of some costly and inappropriate tax shelters. But conforming to those other provisions did not require conformity to Section 199, nor do the merits of the other provisions enacted at the same time make conformity to Section 199 good state policy.

In most of the 25 states that are losing revenue from the domestic production deduction, legislatures never voted to adopt the tax break. Most of those states have “rolling conformity” to the federal tax code, meaning that state tax law is defined by current federal law, so tax changes are incorporated without any action by the state. Therefore, when the federal government in 2004 enacted the deduction, it became part of state law automatically. The remaining states have “fixed-date conformity,” meaning that state law is tied to federal law as of a fixed date, and that date is updated periodically; these updates typically occur as a matter of course and without consideration of specific federal changes involved. The delayed phase-in of the deduction made scrutiny by state lawmakers especially unlikely. The full fiscal impact was delayed until 2010, which at the time of enactment was well outside states’ budget windows (which typically extend only one or two years into the future).

The federal government also did not explicitly consider the tax break’s cost to states. Federal lawmakers are required by law to consider the impact of tax cuts on federal revenue, but almost never give formal consideration to the impact on state revenue.[10]

In short, the federal government passed legislation that altered state tax law, costing states hundreds of millions of dollars. The change took effect without either federal or state lawmakers considering the cost to states.

The domestic production deduction was depicted in some accounts at the time of its enactment as important aid for struggling industries and as a draw for manufacturing jobs. State conformity to the deduction is unlikely to achieve these goals. Furthermore, as they recover from the economic downturn, states have more pressing uses for scarce funds than a subsidy for profitable corporations.

- A state-level domestic production deduction creates little incentive for corporations to create or protect jobs within that state. Firms can claim the domestic production deduction for profits from all qualifying domestic activities — meaning activities that occur anywhere within the United States. As a result, a multi-state firm can claim the deduction in a conforming state for production activities in any state, not just the state where the firm is filing. Thus states have no guarantee that firms claiming the deduction have a single employee working in a qualifying industry in that state.[11]

- The deduction provides little help to struggling businesses, since only profitable ones can use it. The domestic production deduction has been justified as assistance for struggling industries and protection for threatened jobs, but it is poorly designed for these goals. The reason is that the amount of the deduction is tied to a firm’s qualifying profits, and the value of the deduction (like that of all deductions) is limited by a firm’s total profits. As a result, only profitable businesses can claim the deduction, and more profitable businesses benefit more. The deduction takes no account of the number of people a business employs.

This structure — favoring profitable businesses, excluding unprofitable ones, and ignoring employment — makes the deduction particularly ineffective at protecting jobs. Money-losing firms considering layoffs receive little or no benefit. Highly profitable firms benefit disproportionately whether or not they are creating jobs. - The deduction favors large corporations over small businesses. The domestic production deduction has been praised as a boon to small business, but IRS statistics suggest otherwise. Among 2009 corporate income tax returns, 93 percent of the deduction was claimed by the 0.5 percent of firms with assets over $100 million. Many of these large firms are multi-state corporations and may invest little or none of the benefit in the state granting the tax break.[12]

> - State revenues lost to the deduction could be better spent on other priorities. Most states continue to face a slowly recovering economy and high unemployment. Unlike the federal government, states must balance their budgets each year. Many states have passed or are considering budget cuts, actions that may delay the economic recovery. Within this context, corporate tax breaks — especially those costing states hundreds of millions of dollars per year — need to be carefully examined. The high cost of conforming to the domestic production deduction could be better spent on maintaining key services or on closing budget deficits.

From an administrative perspective, decoupling from the domestic production deduction is straightforward. It requires a simple statutory change, is simple to comply with, and does not interfere with state conformity to other federal provisions.

As a statutory matter, decoupling can be accomplished by adding a single sentence to state tax law disallowing the deduction. Compliance is equally simple: corporations just add back the deducted amount to their taxable income. Unlike with other federal tax provisions from which states decouple, such as accelerated depreciation and operating loss carrybacks, decoupling from the domestic production deduction does not require businesses to maintain additional records not required for federal tax compliance.

The domestic production deduction will cost states over $600 million next year. Most states never voted on this tax break, which mostly benefits large corporations, and is unlikely to create any jobs within the state. Twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have already decoupled from the provision, and it is relatively simple, and cost-effective, for the remaining 25 states to follow suit.