Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the August Employment Report

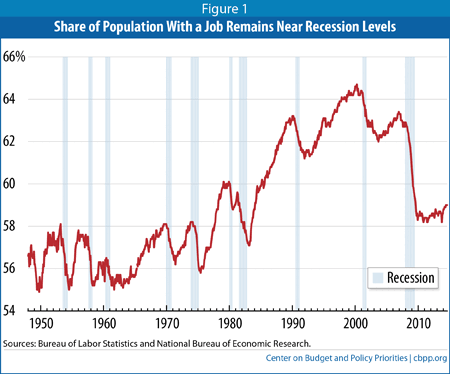

Today’s disappointing jobs report, while perhaps only a blip in an ongoing labor market recovery, is a sober reminder of how devastating the Great Recession and subsequent prolonged jobs slump has been for workers. In particular, the share of the population with a job, which plunged to its lowest levels since the early 1980s, has since risen only modestly even though we’re now more than five years into the recovery (see chart). The share of the labor force that’s working fewer hours than it would like remains high, as does long-term unemployment.

Some of the decline in the share of Americans with a job reflects demographic rather than economic factors — mainly the growing number of baby boomers who have retired. But a significant part reflects not only an elevated unemployment rate but also reduced labor force participation, as many people who want to work have stopped looking until their job prospects improve. A robust economic recovery would cure these problems.

Policymakers’ shortsighted decision not to renew federal emergency unemployment insurance benefits in 2014 eliminated not only valuable financial support for these workers and their families but also a valuable source of consumer spending that would have strengthened demand and put more jobless Americans back to work. It also would have induced more of the long-term unemployed to remain in the labor market looking for work.

About the August Jobs Report

Employers reported only modest payroll growth in August. In the separate household survey, the unemployment rate edged down to 6.1 percent, but most of the decline resulted from labor force attrition, not employment growth.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 142,000 jobs in August and the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised job growth in the previous two months downward by a total of 28,000 jobs. Private employers added only 134,000 jobs in August, while overall government employment rose by 8,000. Federal government employment rose by 3,000, state government rose by 1,000, and local government rose by 4,000.

- This is the 54th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 10.0 million jobs (a pace of 186,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 9.5 million jobs over the same period, or 175,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 571,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 326,000 local government jobs.

- The job losses incurred in the Great Recession have been erased. There are now 1.2 million more jobs on private payrolls and 768,000 more jobs on total payrolls than there were at the start of the recession in December 2007. Because the working-age population has grown over the past six and a half years, however, the number of jobs remains well short of the number of jobs needed to restore full employment. Employers expanded their payrolls at a 240,000-a-month pace in the six months prior to August’s disappointing slowdown; job creation will have to return to that earlier pace to restore normal labor market conditions in a reasonable period of time.

- The unemployment rate edged down to 6.1 percent in August, and 9.6 million people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 5.3 percent for whites (0.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 11.4 percent for African Americans (2.4 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 7.5 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (1.2 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and lack of job opportunities in the ongoing jobs slump kept many potential jobseekers on the sidelines and not counted in the official unemployment rate. This problem was evident in August. Unemployment dropped by 80,000 people, but employment increased by only 16,000 people, while the labor force shrank by 64,000 people.

- As a result of the decline in the labor force, the labor force participation rate (the share of the population aged 16 and over in the labor force) edged down to 62.8 percent in August. While labor force participation is no longer declining, as it did in 2013, it remains at levels last seen in 1978.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 59.0 percent in August, slightly above its 2013 average of 58.6 percent.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — edged down to 12.0 percent in August. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.2 percent in April 2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 3.2 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, about 19 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. More than three in ten (31.2 percent) of the 9.6 million people who are unemployed — 3.0 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 1.9 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983, early in the recovery from the 1981-82 recession. A year after peaking at 2.6 percent, however, the long-term unemployment rate had dropped to 1.4 percent, well below the current rate.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.