Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the December Employment Report

Today’s surprisingly disappointing jobs report should temper recent optimism of an improving labor market in 2014. The climb back to normal levels of employment remains steep. Most notably, the labor force shrank, the share of Americans with a job remains near its low during the Great Recession (see chart), and long-term unemployment remains historically high. Congress should move urgently to restore the emergency federal unemployment insurance benefits that it allowed to lapse at the end of the year, and policymakers also should consider other measures to speed the recovery and help the long-term unemployed find jobs.

The labor market is far from full health. Employers have been expanding their payrolls for almost four years, but job growth was weak in December. Meanwhile, job losses in the Great Recession were so large that nonfarm payroll employment has not yet even returned to where it was at the recession’s start in December 2007. To restore normal levels of employment in a reasonable period of time, job growth must be much stronger than we’ve seen in recent months. That requires stronger growth in demand for goods and services than we’ve seen so far in the recovery.

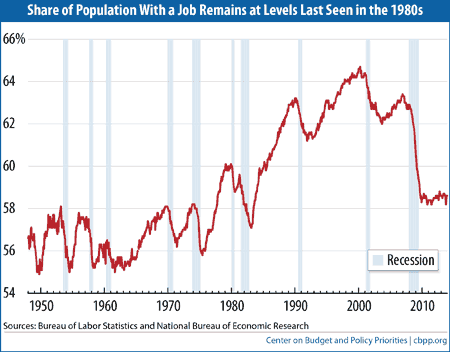

Stronger growth will make more jobs available and, thus, bring more people back into the workforce. Over the course of the recession and recovery, the labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population working or looking for work) has fallen significantly — and it fell again in December. Due to the drop in labor force participation, a falling unemployment rate (including December’s decline to 6.7 percent) has not translated into sufficient growth in employment to significantly boost the percentage of Americans with a job. As the chart shows, that percentage remains stuck at levels last seen in the 1980s.

Stronger growth would also improve job prospects for the long-term unemployed. High long-term unemployment has been one of the most discouraging features of the current recovery. The share of the unemployed who have been looking for work for six months or more remains significantly higher than in any prior recession back to the late 1940s.

To speed up economic growth and job creation, policymakers should (in addition to extending federal unemployment benefits) consider measures like infrastructure investment that raise the demand for goods and services in the short run — and boost the economy’s capacity to supply goods and services in the longer run. To help the long-term unemployed, they also should adequately fund existing employment service programs, and they might consider employment subsidies to give employers a greater incentive to hire the long-term unemployed. To ensure long-term budget stability, they could pay for these measures with a balanced package of revenue increases and spending cuts that largely or entirely takes effect in a few years when the economy is stronger.

This will be a long journey. But quickly restoring emergency jobless benefits would be a good first step.

About the December Jobs Report

Job growth in December was disappointing, and the decline in unemployment largely reflects a smaller labor force rather than strong employment growth. Employment levels remain far below what they would be in a healthy labor market.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by just 74,000 jobs in December and the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised job growth in October and November upward by a total of 38,000 jobs. Private employers added 87,000 jobs in December, while government employment fell by 13,000. Federal government employment fell by 2,000, state government employment fell by 2,000, and local government fell by 9,000.

- This is the 46th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 8.2 million jobs (a pace of 178,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 7.6 million jobs over the same period, or 164,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 621,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 372,000 local government jobs.

- Despite 46 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 1.2 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 638,000 thousand fewer jobs on private payrolls in December than when the recession began in December 2007. December’s job growth (even with the revisions to earlier months) was well below the sustained job growth of 200,000 to 300,000 a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery. Job growth averaged 182,000 a month in 2013, but December’s gains were the smallest of the year.

- The unemployment rate was 6.7 percent in December, and 10.4 million people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 5.9 percent for whites (1.5 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 11.9 percent for African Americans (2.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 8.3 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (2.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and lack of job opportunities in the ongoing jobs slump has kept many potential jobseekers on the sidelines. December followed that pattern. The number of unemployed fell by 490,000, but the number of people with a job rose by only 143,000. The labor force (people aged 16 or over working or actively looking for work) shrank by 347,000 and the labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over in the labor force) fell back to 62.8 percent in December, 0.8 percentage points lower than at the start of the year. Prior to this year, that is the lowest since 1978.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.6 percent in December, which is also its average rate for the year.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 13.1 percent in December. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in late 2009 and early 2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 4.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, about 21 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Nearly two-fifths (37.7 percent) of the 10.4 million people who are unemployed — 3.9 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 2.5 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.