Recovery Act assistance to states will largely run out this year, which could not only eliminate hundreds of thousands of jobs and undermine basic education services but also impede education reform efforts. As Education Secretary Duncan recently told Congress, “We are gravely concerned that the kind of state and local budget threats our schools face today will put our hard-earned reforms at risk.” [1]

The recession has driven down state revenues by record proportions. Education makes up the largest single item in state budgets, and spending cuts there have been deep and widespread. Federal aid through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act has lessened the impact of state budget shortfalls on education and other state services, but that aid will soon be depleted. Meanwhile, serious state budget shortfalls will likely persist for at least the next two years, reaching an estimated $180 billion in fiscal year 2011 (which in most states will begin July 1) and $120 billion in 2012. This sets the stage for even more severe cuts as states wait for revenues to recover to pre-recession levels. For 2011, legislatures and governors are enacting budgets with cuts that go even deeper than those enacted over the past two fiscal years.

To prevent the worsening of education cuts, Congress should temporarily extend both the Medicaid and education-related fiscal relief that the federal government provided over the past year through the Recovery Act. The Medicaid extension is included in “jobs” legislation now pending in the House.

Education cuts already have cost jobs in the economy, and the pain is about to get worse. Even though the funding the Recovery Act has provided through the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (primarily for education) has saved 347,000 jobs, school districts and other local education employers (such as community colleges) have nevertheless cut 105,100 jobs since July of 2008— and this number is very likely to grow. California school districts have notified at least 20,000 teachers that they might be terminated, for example, and Illinois’ governor has proposed education cuts that he estimates would mean layoffs for 17,000 teachers. The end of ARRA funding would likely accelerate this job loss. These job losses — as well as teacher furloughs, salary reductions, cancellation of contracts with private-sector vendors, and other budget-cutting measures — also weaken the overall economy by reducing consumer demand. Without additional federal aid, state budget cuts could cost the economy 900,000 public- and private-sector jobs.

In addition, current and additional education cuts undermine reform initiatives that many states are undertaking with the federal government’s encouragement, such as supporting professional development to improve teacher quality, improving interventions for young children to heighten school readiness, and turning around the lowest-achieving schools, to name just a few. For example, recent state education cuts include reductions in support programs for high-needs students, teacher training and mentoring and funds for professional development, and early childhood programs. The shortage of state and local funding for education is moving programs and policies in a counterproductive direction, and further cuts resulting from the ending of Recovery Act support would exacerbate this trend.

In April 14 testimony, Education Secretary Arne Duncan urged Congress to enact another round of emergency support for schools. He said:

“We are gravely concerned that the kind of state and local budget threats our schools face today will put our hard-earned reforms at risk. … If we do not help avert this state and local budget crisis, we could impede [education] reform and fail another generation of children. The fact is that gaps for special education, low-income and minority students remain stubbornly wide.

“One in four high school students fails to graduate. Forty percent of students who go to college need remedial education. And huge numbers of young people determined to go to college and pursue a career drop out because of financial or academic challenges.

“If we want reform to move forward, we need an education jobs program. Jobs and reform go hand-in-hand.

“It is very difficult to improve the quality of education while losing teachers, raising class size, and eliminating after school and summer school programs.”

Cuts Have Been Broad and Deep — And Will Worsen Unless Congress Extends Aid

Since the start of the recession, most states have cut spending on pre-kindergarten-through-high-school education, higher education, or both. As detailed in Appendix I, at least 30 states and the District of Columbia have implemented cuts to K-12 education. States have reduced general funding to school districts, aid targeted to charter schools, funding for books and classroom supplies, programs for gifted and talented students, pre-kindergarten and after-school programs, and teacher training. In addition, at least 41 states have cut funding to public colleges and universities or instituted large increases in college tuition — and in many cases done both. States have cut enrollment, laid off faculty and staff, reduced financial aid, and eliminated scholarships.

As serious as these cuts have been, they would have been significantly deeper without the federal aid provided through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Both the education-specific aid and the aid not directly targeted to education appear to have averted education cuts.

The Recovery Act included two primary forms of state fiscal relief: an increase in the federal share of state Medicaid expenditures and a State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF) targeted mainly at reducing the extent of education cuts. Together, they provided states with nearly $140 billion over two and a half years. The SFSF dollars alone are funding 347,000 jobs, mostly in education, according to the Department of Education. [2] The increased Medicaid support has also helped protect education programs and jobs by reducing the cost to states of meeting the rise in health care needs — freeing up state funds for education and other purposes.

But the Recovery Act funding is about to run out, even as states still face large budget shortfalls in 2011 and 2012 due to the continued decline in revenues. The additional Medicaid support expires at the end of December 2010, the midpoint of the next fiscal year in most states. SFSF funds are also waning. The Department of Education had obligated 89 percent of the SFSF funds to states as of May 14[3] and is expected to obligate the rest over the next couple of months. [4]

In their applications for SFSF assistance, states indicated that they planned to spend more than 86 percent of the assistance by the end of fiscal year 2010 (June 30 in most states), and state budget documents confirm that states are in fact spending the money that rapidly. A CBPP analysis of budget documents in 17 states finds they will have spent 71 percent of their SFSF allocations by the end of June. [5] Nearly all of the remaining SFSF funds (99.6 percent) will be spent by the end of the 2011 fiscal year.[6]

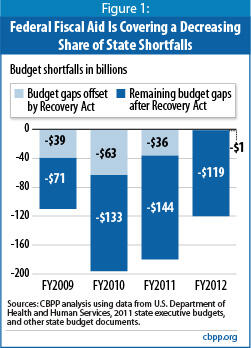

As crucial as the Recovery Act assistance has been, the length and severity of the national recession mean that the aid will run out before state revenues recover to the point where states can balance their budgets without deep cuts to important services. In fiscal year 2011, state shortfalls are likely to be $180 billion, nearly as large as in 2010. And in 2012, states still will face about $120 billion in shortfalls. These are very large by historical standards. Recovery Act assistance closed 32 percent of states’ shortfalls in 2010, but will cover just 20 percent of their shortfalls in 2011 and less than 1 percent of their shortfalls in 2012 as the aid phases out (see Figure 1).

Moreover, states likely will need federal aid to cover a larger percentage of their shortfalls in 2011 and 2012 than in 2009 and 2010 because they will have mostly exhausted the reserve funds and other one-time revenue sources they used to help preserve services in those earlier years.

Unless Congress extends Recovery Act assistance, therefore, states will continue to reduce services. But the negative impact of these cuts goes even deeper. Cuts of the magnitude states have been imposing also slow the economy and cost jobs, as states lay off workers, reduce payments to private-sector providers, cancel contracts, and purchase less. The loss just in public-sector employment to date has been considerable: local governments (primarily school districts plus some community college systems) have cut 105,100 education jobs since July 2008, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (That is in addition to the loss of over 100,000 non-education jobs in state and local government.) And Mark Zandi, Chief Economist of Moody’s Economy.com, has warned that the state budgetary actions expected if Congress does not extend state fiscal assistance “will be a serious drag on the economy at just the wrong time.”[7] It has been estimated that without an extension of state fiscal relief, state spending cuts could mean nationwide job loss of up to 900,000 in both the public and private sectors. [8] Council of Economic Advisers chair Christina D. Romer said in an April 17 speech that additional aid to states is “likely to be very effective” in raising income and employment.[9]

Legislation to extend the Recovery Act’s Medicaid support for six months has passed both the Senate and the House, and President Obama included the provision in his 2011 budget.[10] This assistance would be very helpful to states, though they would still have to impose severe cuts in state spending. By also extending the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund, policymakers could save jobs, support the economic recovery, and preserve the public services that residents expect and need.

In addition to helping states mitigate cuts in services and hold down job losses, an extension of state fiscal relief would help sustain state education reform efforts.

Congress set aside a small portion of Recovery Act funds, $4.4 billion for the new “Race to the Top” initiative, as competitive grants for specific education reform efforts. Perhaps more important, the Recovery Act’s fiscal relief for states — including the Medicaid funds and the portion of the SFSF consisting of categorical grants to states for education and other services — has supported state education reform efforts that otherwise would be in grave peril due to the recession.

By lessening the severity of state education funding cuts, the federal aid has allowed states to continue to pursue key reform initiatives, many of which mirror federal goals in such areas as improving teacher quality, turning around low-performing schools, improving early education, extending learning time, and expanding access to higher education.[11]

At the same time, though, state funding cuts are placing a wide range of reform efforts at risk. Those cuts will get worse if the Recovery Act’s fiscal relief expires. For example:

- Research suggests that teacher quality is the most important determinant of student success, and is a major emphasis of the Administration’s “Race to the Top” program. Recruiting, developing, and retaining high-quality teachers is generally thought to be critical to improving student achievement.[12] But these tasks are much more difficult when school districts are cutting their budgets. Since teacher salaries make up a large share of public education expenditures, funding cuts inevitably restrict districts’ ability to expand teaching staffs and supplement wages. Indeed, numerous school districts have reduced teacher wages through furloughs since the start of the recession and have resorted to hiring freezes. Moreover, states like Maryland, Massachusetts, and Washington as well as local school districts have cut funding for professional development, which makes it more difficult to develop teachers’ skills.

- Twenty-three states have implemented policies to bring class sizes below 20 students per classroom. There is evidence to suggest that smaller class sizes can boost achievement, especially in the early grades. Yet small class sizes are difficult to sustain when schools are cutting teaching positions while enrollments increase.[13] Indeed, a survey of school administrators found that 26 percent of respondents increased class sizes for the 2009-10 school year, and 62 percent anticipate doing so for the 2010-11 school year. [14] States where cuts are specifically linked to class size increases include Georgia and Washington, as described in the Appendix.

- Many states are working to increase student learning time, such as by lengthening the school year. [15] Also, 35 states and the District of Columbia encourage or require schools to offer summer learning programs.[16] Many education policy experts believe that more student learning time can improve achievement. In a number of states and school districts, however, budget cuts are making it more difficult to extend instructional opportunities. For example, Hawaii’s schools are closing on Fridays because of teacher furloughs, New Jersey’s funding cut for afterschool programs will limit structured learning time, and in a 2009 survey of California parents, 41 percent of respondents reported that their child’s school was cutting summer programs.[17]

Moreover, reductions in the education workforce make it less likely that schools will have adequate personnel to teach and supervise students for additional periods of time or to give additional attention to students who are having difficulty learning, despite state and federal goals to lessen disparities among achievement levels. Cuts that limit student learning time are likely to intensify in the coming year. The school administrators’ survey mentioned above found that 13 percent of respondents were considering shortening the school week to four days for the 2010-11 school year and 34 percent were considering eliminating summer school.[18] - As of the 2006-07 school year, 38 states provided pre-kindergarten or pre-school programs, serving over 1 million children. A number of studies conclude that such programs can improve cognitive skills, especially for disadvantaged children.[19] Since the start of the recession, however, Arizona, Illinois, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and other states have cut funding from early education programs to help close their budget shortfalls.

- Expanding access to higher education is a central component of many state education reform efforts. State budget cuts since the start of the recession, however, have had the opposite impact. Tuition increases at public colleges and universities in states such as Arizona, California, Florida, and New York, and financial aid reductions in states such as Michigan, New Mexico, and Washington have made college less affordable for low- and moderate-income students, many of whom are also facing increased financial hardship.

At a time when the nation is trying to produce workers with the skills to master new technologies and adapt to the complexities of a global economy, policymakers’ failure to help states avert large cuts in education funding would undermine a crucial building block for future prosperity.

K-12 Education and Other Childhood Education Programs

At least 30 states and the District of Columbia have cut K-12 education spending.

- Arizona eliminated preschool for 4,328 children, funding for schools to provide additional support to disadvantaged children from preschool to third grade, aid to charter schools, and funding for books, computers, and other classroom supplies. The state also halved its funding for kindergarten, leaving school districts and parents to shoulder the cost of keeping children in school beyond a half-day schedule.

- California reduced K-12 aid to local school districts by billions of dollars and is cutting a variety of programs, including adult literacy instruction and help for high-needs students.

- Colorado has reduced public school spending by $260 million, nearly a 5 percent decline from the previous year. The cut amounts to more than $400 per student.

- Georgia reduced K-12 education spending by $403 million or 5.5 percent. The cut has led the state’s board of education to exempt local school districts from class size requirements to reduce costs.

- Hawaii shortened the current school year by 17 days and is furloughing teachers for those days.

- Illinois reduced funding for early childhood education by 10 percent, which could cause as many as 10,000 children to lose eligibility.

- Maryland cut professional development for principals and educators, as well as health clinics, gifted and talented summer centers, and math and science initiatives.

- Michigan cut its FY 2010 school aid budget by $382 million, resulting in a $165 per-pupil spending reduction.

- Mississippi cut its FY 2010 funding for K-12 education by 9.5 percent, mostly out of the Mississippi Adequate Education Program established to bring per-pupil spending up to adequate levels in every district.

- Massachusetts cut Head Start, universal pre-kindergarten programs, and early intervention services to help special-needs children develop appropriately and be ready for school. The state also cut K-12 funding, including for mentoring, teacher training, reimbursements for special education residential schools, services for disabled students, and programs for gifted and talented students.

- New Jersey cut funding for afterschool programs aimed to enhance student achievement and keep students safe between the hours of 3 and 6 p.m. The cut will likely cause more than 11,000 students to lose access to the programs and 1,100 staff workers to lose their jobs.

- Rhode Island cut state aid for K-12 education and reduced the number of children who can be served by Head Start and similar services.

- Virginia’s $700 million in cuts for the coming biennium include the state’s share of an array of school district operating and capital expenses and funding for class-size reduction in kindergarten through third grade. In addition, a $500 million reduction in state funding for some 13,000 support staff such as janitors, school nurses, and school psychologists from last year’s budget was made permanent.

- Washington suspended a program to reduce class sizes and provide professional development for teachers; the state also reduced funding for maintaining 4th grade student-to-staff-ratios by $30 million.

- State education grants to school districts and education programs have also been cut in Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Nebraska, Nevada, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, and Utah.

Colleges and Universities

At least 41 states have cut funding to public colleges and universities or instituted large increases in college tuition — and in many cases done both.

- Arizona’s Board of Regents approved in-state undergraduate tuition increases of between 9 and 20 percent as well as fee increases at the state’s three public universities. Additionally, the three state universities must implement a 2.75 percent reduction in state-funded salary spending and plan to do so through a variety of actions, such as academic reorganization, layoffs, furloughs, position eliminations, hiring fewer tenure-eligible faculty, and higher teaching workloads.

- The University of California is increasing tuition by 32 percent and reducing freshman enrollment by 2,300 students; the California State University system will cut enrollment by 40,000 students.

- Colorado funding for higher education was reduced by $62 million from FY 2010 and this has led to cutbacks at the state’s institutions. For example, the University of Colorado system will lay off 79 employees in FY 2011 and has increased employee workloads and required higher employee contributions to health and retirement benefits.

- Georgia cut state funding for public higher education for FY2011 by $151 million, or 7 percent. As a result, undergraduate tuition for the fall 2010 semester at Georgia’s four public research universities (Georgia State, Georgia Tech, the Medical College of Georgia, and the University of Georgia) will increase by $500 per semester, or 16 percent. Community college tuition will increase by $50 per semester.

- The University of Idaho has responded to budget cuts by imposing furlough days on 2,600 of its employees statewide. Furloughs will range from four hours to 40 hours depending on pay level.

- Florida cut university budgets and community college funding and raised tuition at its 11 public universities by 15 percent in the 2009-10 school year. The University of Florida will eliminate 150 positions this year, including layoffs of over 50 staff and faculty; Florida State University is laying off up to 200 faculty and staff.

- Indiana’s cuts to higher education have caused Indiana State University to plan to lay off 89 staff.

- Michigan is reducing student financial aid by $135 million (over 61 percent), including decreases of 50 percent in competitive scholarships and 44 percent in tuition grants, as well as elimination of nursing scholarships, work-study, the Part-Time Independent Student Program, Michigan Education Opportunity Grants, and the Michigan Promise Scholarships.

- New Mexico eliminated over 80 percent of support to the College Affordability Endowment Fund, which provides need-based scholarships to 2,366 students who do not qualify for other state grants or scholarships.

- New York’s state university system increased resident undergraduate tuition by 14 percent beginning with the spring 2009 semester.

- South Dakota’s fiscal year 2011 budget cuts state support for public universities by $6.5 million and as a result the Board of Regents has increased university tuition by 4.6 percent and cut university programs by $4.4 million.

- Texas instituted a 5 percent across-the-board budget cut that reduced higher education funding by $73 million.

- Virginia’s community colleges implemented a tuition increase during the spring 2010 semester.

- Washington reduced state funding for the University of Washington by 26 percent for the current biennium; Washington State University is increasing tuition by almost 30 percent over two years. In its supplemental budget, the state cut 6 percent more from direct aid to the state’s six public universities and 34 community colleges, which will lead to further tuition increases, administrative cuts, furloughs, layoffs, and other cuts. The state also cut support for college work-study by nearly one-third and suspended funding for a number of its financial aid programs.

- Other states cutting higher education operating funding and financial aid include Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, and Wisconsin.