- Home

- Chart Book: Deficit Reduction, The Econo...

Chart Book: Deficit Reduction, the Economy, and the Budget Negotiations

Sharon Parrott, Richard Kogan, Krista Ruffini, and William Chen

The House and Senate, which passed starkly different ten-year budget plans this spring, have convened a conference committee that will likely focus on whether (and how) to replace some or all of the sequestration cuts in place for fiscal year 2014 and perhaps 2015, rather than on a broader long-term budget plan.

The 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) set tight limits on discretionary (non-entitlement) funding through 2021 and called for additional annual cuts — known as sequestration — if Congress failed to agree on a deficit-reduction plan later in 2011. The cuts are evenly divided between non-defense and defense programs, which will be cut by a combined $109 billion each year. Most, but not all, of the cuts come from discretionary programs. Though intended to be a “stick” that would force Congress to compromise on a deficit-reduction plan, these cuts have taken effect.

Policymakers in both parties have criticized sequestration as shortchanging important domestic investments — including scientific research, public health, law enforcement, education, and environmental protection — and forcing significant defense reductions.

The following charts illustrate:

- what has happened to deficits since the recession hit (Part I);

- what policymakers have done to reduce deficits (Part II);

- why vulnerable Americans have much at stake in the current talks (Part III);

- why the weak economy should be part of the budget negotiations (Part IV);

- why tax breaks are a potential source of substantial deficit savings (Part V); and

- how policymakers should evaluate deficit-reduction proposals (Part VI).

Part I: Deficits Have Fallen Significantly Since the Recovery Began

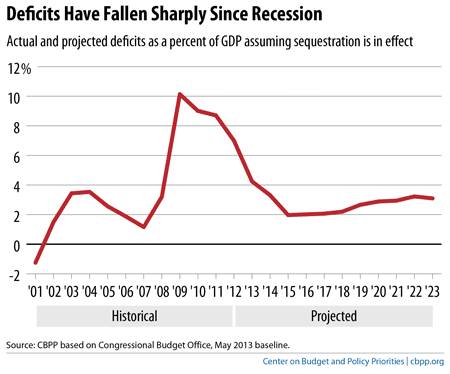

Deficits grew significantly as a share of the economy (gross domestic product, or GDP) during the Great Recession for three reasons. Federal spending rose because of “automatic stabilizer” programs such as unemployment insurance and SNAP, as well as temporary stimulus measures; tax revenues declined as individuals and businesses earned less; and GDP declined as the economy slowed.

Since 2010, deficits have been on a sharp downward path. In 2013, the deficit fell to about 4 percent of GDP. Assuming sequestration continues, by 2015 the deficit will fall to about 2 percent of GDP — less than the average of the four decades from 1969 to 2008 — and stay there through 2018. (Even if sequestration were canceled and not replaced with alternative deficit reduction, deficits over this period would be less than 3 percent of GDP.)

After 2018, deficits as a share of GDP will begin to rise modestly, but they are projected to remain below 3 percent of GDP through 2021. The aging of the population and rising health care costs will continue to place modest but consistent upward pressure on deficits and debt over subsequent decades, so longer-term deficit reduction remains important. Over the next decade, the United States does not face a “debt crisis” that endangers the economy.

Part II: If Sequestration Remains, Policymakers Will Have Cut Deficits by Nearly $4 Trillion, Largely Through Spending Cuts

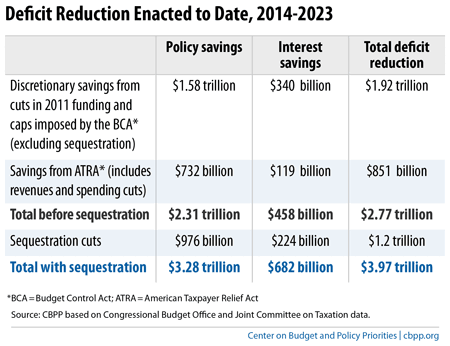

Policymakers have enacted several deficit-reduction measures since 2010, including cuts to appropriations in 2011, the 2011 Budget Control Act, and the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) in early 2013. Taken together, these measures will shrink deficits by nearly $4 trillion over the 2014-2023 period, if the sequestration cuts remain in place or policymakers replace them with comparable deficit-reduction measures over the decade.

This nearly $4 trillion in deficit reduction reflects the impact of policy changes and the accompanying interest savings. It doesn’t count the effects of an improving economy or the expiration of temporary stimulus measures.

These policy savings primarily come from cuts in discretionary programs, including the BCA cuts. The BCA capped funding for discretionary programs and called for sequestration if Congress failed to enact other deficit-reduction legislation. ATRA cut deficits primarily by raising taxes for the highest-earning Americans.

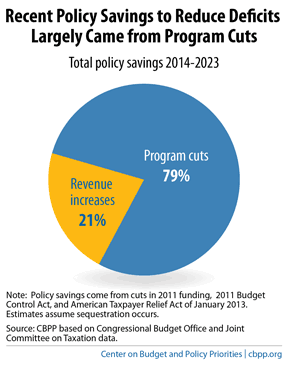

Overall, with sequestration in place, 79 percent of the deficit reduction over 2014-2023 resulting from policy changes will come from spending cuts; 21 percent will come from increased revenues. Even if we replaced half of the sequestration cuts in 2014 and beyond with added revenues, nearly two-thirds of the deficit reduction achieved over the 2014-2023 period would come from spending cuts.

Non-Defense Discretionary Programs Have Been Hit Hard

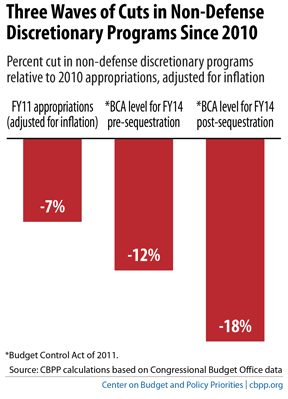

Non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs include a broad set of public services, including basic scientific and medical research, K-12 and preschool education, environmental protection, law enforcement, and international assistance.

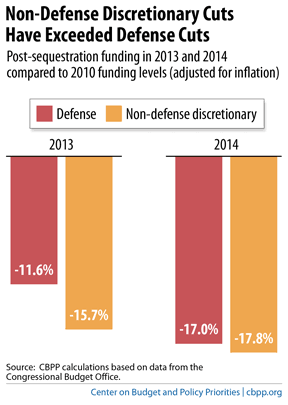

Policymakers have cut NDD programs in three waves: in the 2011 appropriations bills, then under the BCA funding caps, and finally through sequestration. If sequestration remains in effect, NDD in 2014 will be 18 percent below its level in 2010, adjusting only for inflation. (We use 2010 because it is the last year before Congress began cutting discretionary funding.)

Sequestration Does Not Unduly Target Defense in 2014

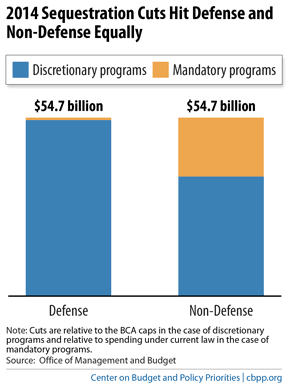

Some claim that sequestration hits defense programs particularly hard in 2014. In reality, however, the $109 billion in sequestration cuts for 2014 are evenly divided between defense and non-defense programs.

Because of one-time changes that policymakers made in 2013, defense received more funding that year than originally called for under the BCA. Thus, defense discretionary funding must fall by $20 billion between 2013 and 2014 to meet the sequestration target for 2014. Those one-time changes did not help NDD funding, which in 2013 roughly equaled what the BCA originally called for under sequestration. Thus, NDD does not have to fall further between 2013 and 2014 to meet the 2014 sequestration target; it will remain flat in nominal terms (and decline modestly in inflation-adjusted terms) if sequestration remains in place.

Regardless of the year-to-year changes between 2013 and 2014, NDD is cut more deeply than defense when one compares its 2014 funding level under sequestration to its 2010 funding level, adjusted for inflation.

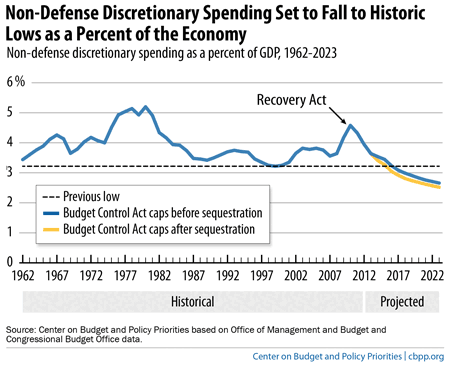

Non-Defense Discretionary Spending Is Falling to Historically Low Levels, Even Without Sequestration

NDD spending as a share of the economy is on a sharp downward path as a result of the cuts enacted since 2010. Whether the sequestration cuts continue or not, NDD spending will reach its lowest share of the economy on record by 2016 (in data that go back to 1962).

Part III: Budget Negotiations and Vulnerable Americans

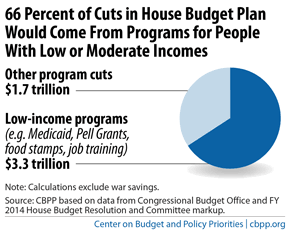

Some policymakers may seek to replace the sequestration cuts with harmful cuts to low-income entitlement programs. The House-passed budget plan, authored by House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, secured nearly two-thirds of its $5 trillion in spending cuts over ten years from programs targeted on people of modest means. Most of these cuts were to low-income entitlements, including SNAP and Medicaid.[1]

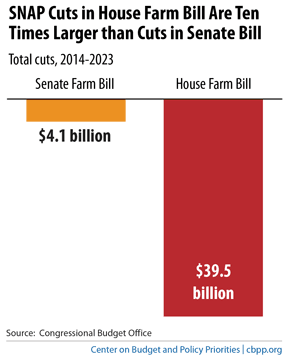

Both the House and Senate Farm Bills include cuts in nutrition assistance for low-income households, but the cuts in the House bill are far more damaging: $39.5 billion over the next decade, 98 percent of which would come directly from food assistance benefits. The Senate-passed Farm Bill, by contrast, includes $4 billion in SNAP cuts, one-tenth the size of the cuts included in the House bill.

The House bill achieves most of its nearly $40 billion in cuts by terminating SNAP benefits entirely to certain groups, including ending benefits after three months for jobless adults without children who live in areas of high unemployment. It also ends benefits for some low-income working families with high expenses for child care or housing and some low-income seniors.

Large-scale deficit-reduction packages enacted in 1990 and in 1993 and the smaller 1997 package adhered to the principle that deficit reduction should not increase poverty or hardship. More recently, fiscal commission co-chairs Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles reaffirmed this principle.

Part IV: The Weak Economy and the 2014 Budget Debate

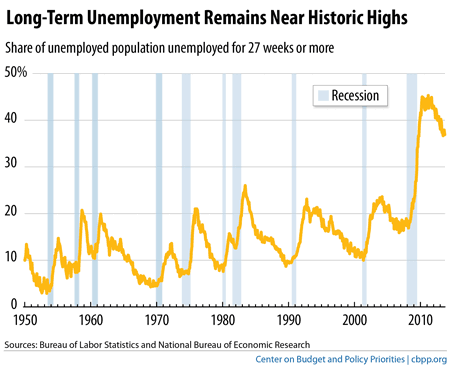

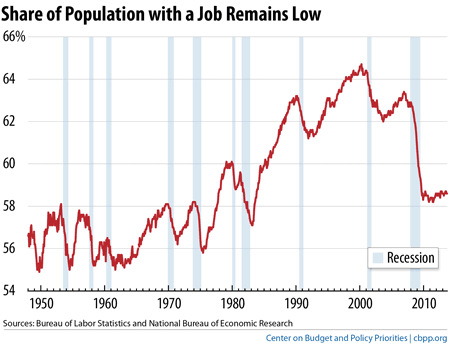

The current budget negotiations occur against a backdrop of continued economic weakness. Despite 43 consecutive months of private-sector job growth, unemployment — and long-term unemployment — remain high, and the share of the population with a job has improved only modestly since the depths of the recession.

Sequestration is hampering economic growth and job creation. According to the Congressional Budget Office, if policymakers had enacted legislation last summer to cancel the 2013 and 2014 sequestration cuts, the economy would have 900,000 more jobs — and GDP would be 0.7 percent larger — in the third quarter of next year than under current projections.

To be sure, we need, at a minimum, to stabilize the debt as a percentage of the economy over the longer term. The best approach would be to replace sequestration with a package that contains sizeable alternative deficit-reduction measures — including both spending cuts and revenues — that take effect gradually as the economy and labor market strengthen, as well as temporary, upfront measures to boost job creation now. Such a package could do more than sequestration to reduce deficits and stabilize the debt over the medium and long term, while encouraging economic growth in the near term.

Part V: Tax Expenditures Are a Source of Alternative Deficit Reduction

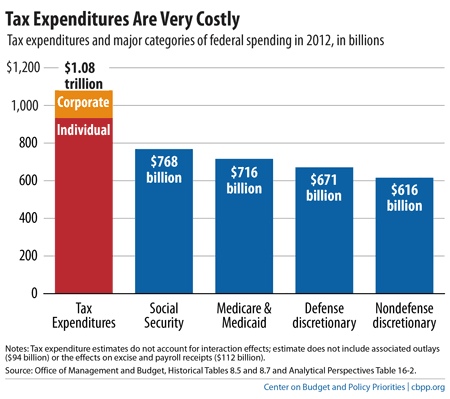

Tax expenditures — spending done through the tax code by way of tax breaks such as exclusions, deductions, and credits — reduced revenues by more than $1 trillion in 2012. That amount exceeds the cost of Medicare and Medicaid combined, Social Security, defense discretionary spending, or non-defense discretionary spending.

Policymakers in both parties have called for scaling back tax expenditures to make the tax code more efficient and to generate savings. Some, however, want to devote all of the savings to lowering tax rates, while others want to use some of the savings for deficit reduction, to ease sequestration, and/or to invest more in education and other building blocks of long-term economic growth.

Part VI: Principles for Proposals to Replace Sequestration

Policymakers should use four criteria to evaluate proposals to replace sequestration:

- Do they strengthen the economic recovery, or do they weaken or slow the recovery?

- Do they protect low-income Americans and avoid increasing poverty and hardship, a principle embraced by leaders of both parties in past deficit-reduction efforts?

- Do they permit adequate investment in core public services, including building blocks of economic growth such as infrastructure, education, and research, as well as efforts to expand economic opportunity?

- Do they reflect a balanced approach, both between budget cuts and revenue increases and between defense and non-defense funding?

End Notes

[1] Our analysis of the House budget compared it to the BCA funding levels without sequestration. (Also, it did not include the reduction in war costs assumed by the House budget.) If one compared the House budget to the BCA funding levels with sequestration, its total savings would be modestly lower but the share of those cuts coming from low-income areas would be modestly higher.

More from the Authors