BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With Millions Facing Serious Hardship, McConnell Plan Doesn’t Meet Nation’s Needs

Despite data showing millions of households without enough to eat or behind on rent, continued high unemployment — particularly among lower-paid workers — and enormous state and local budget shortfalls, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell released a “skinny” relief package today with no food or rental assistance, no state or local fiscal relief beyond insufficient school aid, and a short-term fix to jobless benefits that cuts the previous $600 weekly benefit in half.

The latest data on hardship, the economy, and state and local budgets make clear a much stronger package is essential.

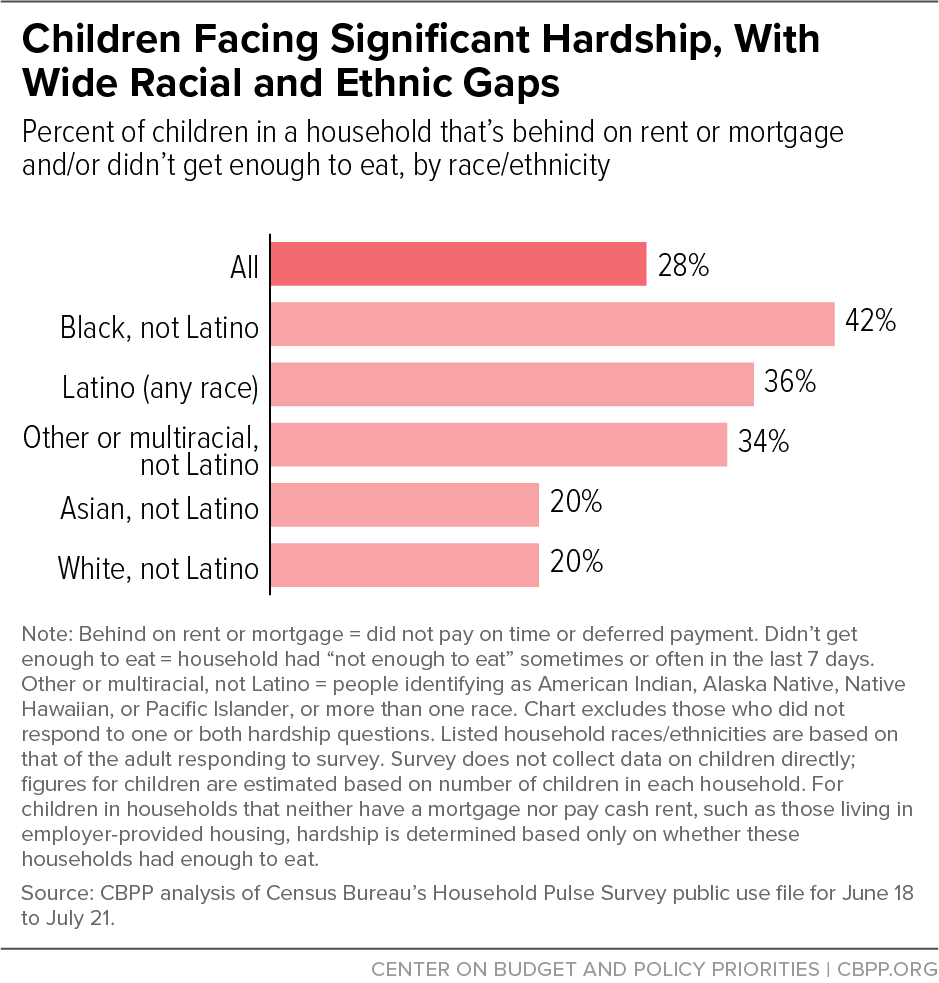

Hardship levels are extremely high. Some 29 million adults reported that their household didn’t get enough to eat, and nearly 15 million adults reported being behind on rent, according to the most recent Census Household Pulse Survey data available (for the week ending July 21). Some 19 million children — fully 1 in 4 — lived in a household in which people weren’t getting enough to eat, that was behind on the rent or mortgage, or both, based on survey data collected from June 18 to July 21. (The Census Bureau will make new hardship data available later this week.)

There is some bipartisan support for nutrition and rental assistance to address these alarming rates of hardship. For example, Republican Senators Grassley, Fischer, Ernst, Boozman, Hoeven, and Gardner have expressed support for including a SNAP (food stamp) increase, with other agriculture measures, in a relief package. And Treasury Secretary Mnuchin said last week, “Our first choice is to have bipartisan legislation that allocates specific rental assistance to people hardest hit.”

Nevertheless, the McConnell package includes no nutrition assistance to help families put food on the table or rental assistance to help them pay the rent.

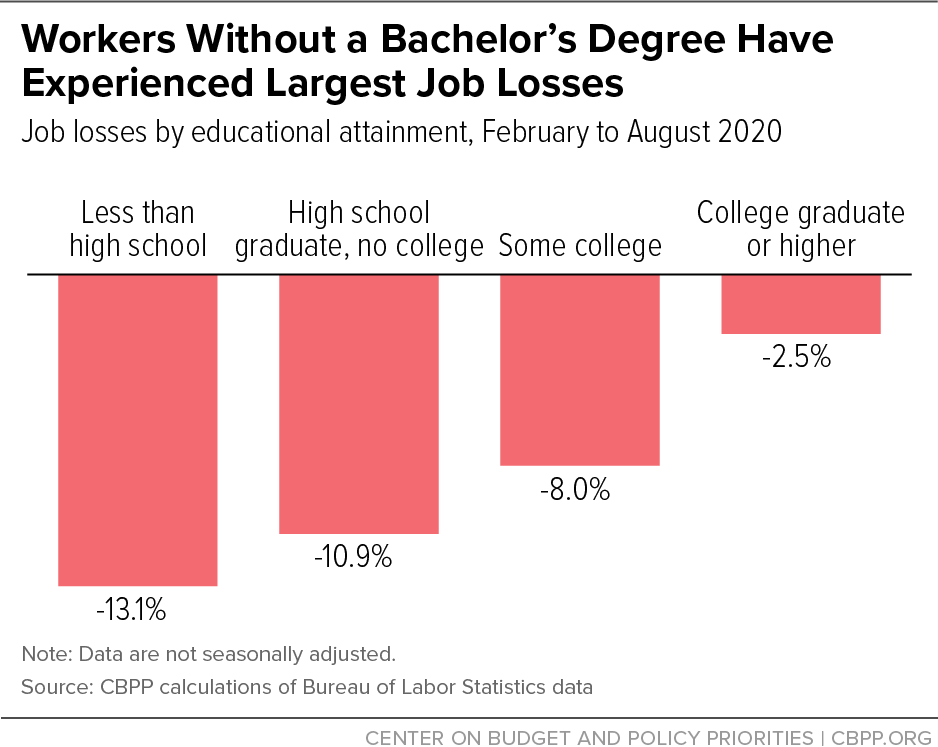

Job losses are high, particularly for lower-paid workers. While the unemployment rate fell in August, the economy still has 11.5 million fewer jobs than in February. The damage has been greatest for workers who are paid low wages and don’t have a four-year college degree.

If industries are divided into three groups by average wages, with roughly the same number of jobs in each group, low-wage industries accounted for 51 percent of jobs lost from February to August. Similarly, the number of people aged 25 and over with a job fell by only 2.5 percent between February and August for those with a four-year college degree, but by 10.9 percent for those with a high school diploma who lacked any college education. Unemployment is particularly high among Black and Latino workers, who face a myriad of challenges, including structural racism, inadequate educational opportunities, and employment discrimination.

Nevertheless, the McConnell package extends federal supplemental jobless benefits only through December and cuts the previous $600 benefit in half. In addition, it doesn’t increase the number of weeks of unemployment benefits that a jobless worker can receive, even though large numbers of unemployed workers will begin exhausting their benefits in the final months of this year and early next year. Policymakers might be able to address this problem in December, but that would depend on the whims of a lame-duck session of Congress meeting after a divisive election, and no one should count on that.

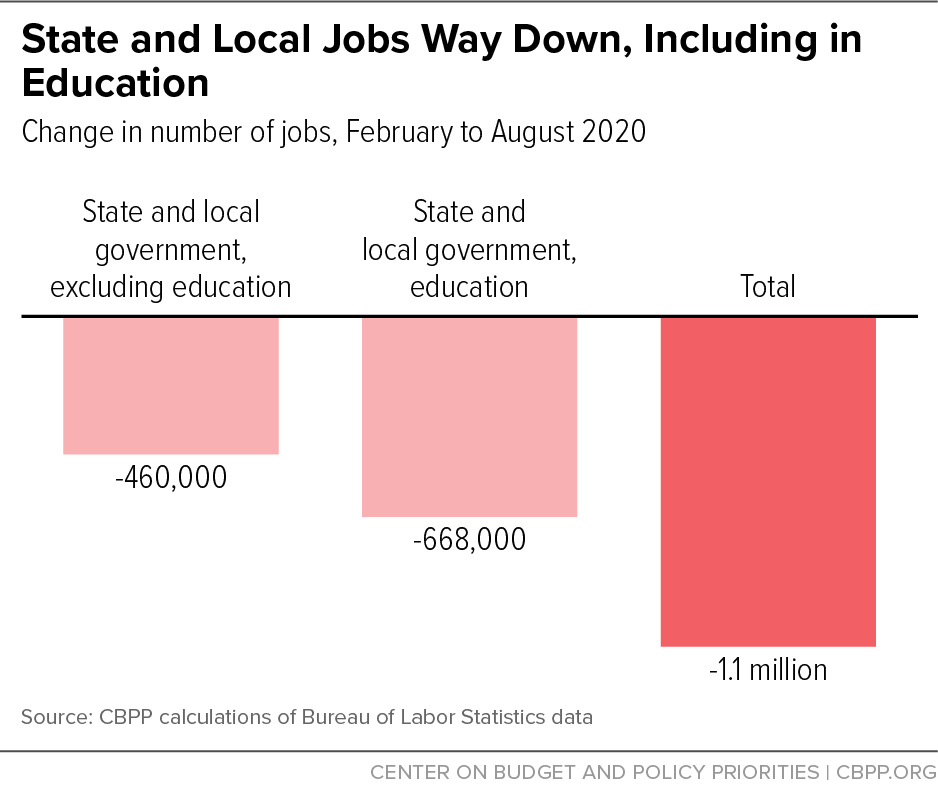

States and localities face deep budget shortfalls. States across the nation, with governors of both parties, face large shortfalls this fiscal year, which in most states started July 1. States and localities have started making cuts — indeed, they cut 1.1 million jobs between February and August, about 60 percent of them in K-12 and higher education. These job losses far exceed those during the Great Recession of a decade ago and its aftermath. Of particular concern, many states are waiting to make more and substantially deeper cuts or to take other steps to help balance their budgets such as raising taxes, hoping that the federal government will come through with significant fiscal relief.

But time is running out, as most states are already part-way through the third month of their fiscal year. Economists Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics and Glenn Hubbard, Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, both said recently that significant fiscal relief to states and localities is essential. Without broad-based relief soon, states and localities will make deeper cuts in areas including education, Medicaid and other health care, transportation, and aid to struggling families. These cuts will lead to more layoffs, slow the economy, and harm the people least able to cope with diminished state and local services.

Here, too, there is bipartisan support for fiscal relief — the bipartisan National Governors Association has called for robust relief well beyond school aid, and Senators Cassidy, Hyde-Smith, and Collins have introduced a bill to provide $500 billion in state and local relief. Nevertheless, the McConnell package includes only $105 billion in school aid, with no broader relief to shore up state finances. Further, those funds would mostly go to schools that reopen irrespective of the health risks, which could push some schools to reopen prematurely and leave districts that can’t reopen safely without the resources needed for adequate remote instruction.

Finally, though overly restrictive federal rules prevent states from using the funds provided through the CARES Act’s Coronavirus Relief Fund to address their revenue shortfalls, the McConnell package doesn’t even provide states with this needed broader flexibility. (The McConnell plan would extend the time available to spend the funds, but that doesn’t address the larger issues states are facing: to avert severe budget cuts, they need additional resources that they can use to fill in for falling revenue.)

The evidence is clear: the nation must do much more than Senator McConnell is proposing in order to reduce the alarmingly high number of households without enough to eat, avert a spike in evictions (either now or when eviction moratoriums end), and forestall deep cuts in state and local services that would hurt the economy, shortchange children’s education, and lead to health care cuts during the pandemic as well as further widespread suffering.