BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Because access to a safe, stable home is indispensable to social distancing, upcoming COVID-19 relief legislation should place a high priority on protecting the lowest-income renters from losing their homes and ending up doubled up, in crowded shelters, or on the streets — and on providing stable homes to those who lack them. Specifically, it should fund at least 500,000 new Housing Choice Vouchers for people experiencing homelessness and others needing sustained help to afford housing. It should also include large-scale funding for short-term emergency rental assistance, which the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) could provide through the Emergency Solutions Grants program.

The poor housing conditions for many low-income people are likely a major reason why the pandemic has disproportionately hit neighborhoods with lower incomes and larger percentages of people of color, according to early data, and why Black Americans have had higher rates of infection and death. Most plainly, people experiencing homelessness — 568,000 on a single night in 2019, 40 percent of them Black, according to HUD data — lack private living spaces where they can isolate from others, so they’re now more exposed to illness and potentially death. Many other low-income people live in housing that’s overcrowded, has health hazards such as vermin or lead contamination, or places them at risk of domestic violence — problems making it dangerous and sometimes impossible to shelter in place for months on end.

In addition, even before the pandemic hit, 11 million low-income households spent more than half of their income on rent and utilities. Many of them risk losing their homes if they lose income due to the pandemic. And, many low-wage workers were employed in hard-hit sectors of the economy; some won’t qualify for unemployment benefits, and many with limited skills may struggle to find jobs when the economy begins recovering and their temporary federal unemployment benefits expire.

Evictions would inflict considerable hardship and increase health risks. Some families would have to double up with others or move into shelters or onto the street. Some states have placed moratoriums on evictions, and the CARES Act prohibits new eviction filings in federally backed housing. But these protections don’t cover many renters, and those who are covered will often accumulate unpaid back rent and face eviction when the moratorium ends.

Short-term rental assistance can get many households through the pandemic. The most vulnerable people, however, will need more sustained help. For example, the CARES Act’s homelessness funding will enable communities to move a sizable number of people from the streets and shelters into safer, temporary housing, but many will risk returning to homelessness when that assistance runs out. That’s why the federal government should also fund 500,000 new Housing Choice Vouchers, which would help families rent modest homes in the private market until they can afford housing on their own.

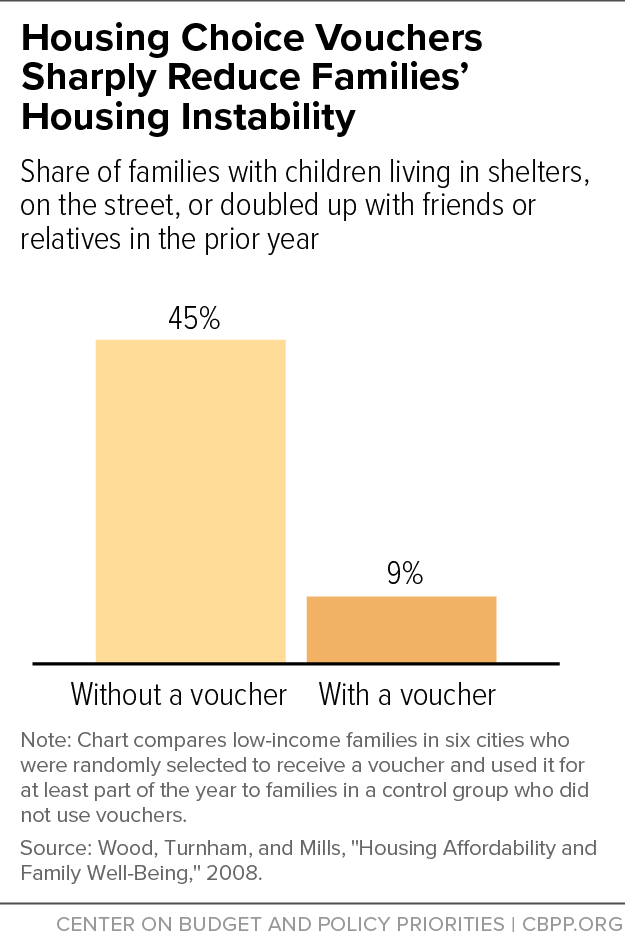

Housing vouchers are the single most effective policy to reduce homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding among extremely low-income people, rigorous research shows. (See chart.) Moreover, the voucher program is well positioned to respond to an emergency. The 2,200 state and local agencies that administer it have the expertise and capacity to help many more families quickly, and HUD has already issued waivers to adapt the program to the current situation (for example, letting agencies suspend in-person inspections of housing where families use vouchers). Vouchers proved effective in addressing emergency housing needs following disasters ranging from the 1994 Northridge earthquake to Hurricane Katrina, and they should be part of our response to the current crisis.

Ideally, when families that get new vouchers no longer need them (in most cases, because their income rebounded as the economy recovered), the vouchers would go to other low-income families struggling to keep a roof over their heads, most of whom don’t receive any rental assistance due to the program’s funding limitations. Rental assistance has powerful, positive effects on housing stability, children’s health and development, and other important family outcomes. But if policymakers don’t want to add these new vouchers to the ongoing voucher stock, they can let them expire as families leave the program because those families can afford housing on their own.