BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Update, November 13: We’ve updated this post to incorporate revised data the Census Bureau released in October.

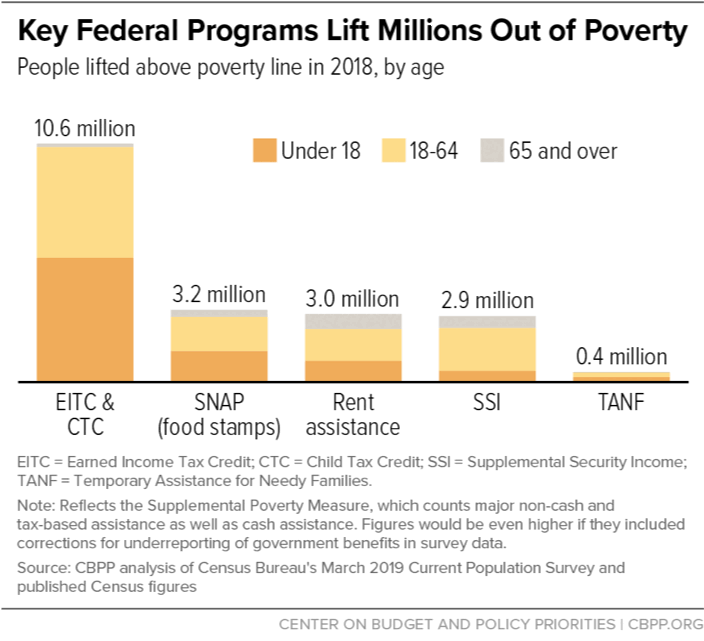

Economic hardship would be far more pervasive without key anti-poverty programs, Census data released today show, with programs like SNAP (food stamps), the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the Child Tax Credit, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) keeping millions of people above the poverty line in 2018.

The Trump Administration has targeted a number of key assistance programs for significant cuts, including SNAP, SSI, rent subsidies, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), both through the President’s proposed 2020 budget and the Administration’s regulatory actions (see here, here, and here).

Programs targeted for cuts are keeping millions from poverty, the Census data show. These figures use the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which accounts for taxes and non-cash benefits and presents a more complete picture of the impact of anti-poverty programs than the official poverty measure, which counts only cash income.

The new data show that in 2018:

- SNAP lifted 3.2 million people above the SPM poverty line ($28,166 for a typical two-adult, two-child renter family). More detailed past analyses have found that SNAP lifts more poor children out of “deep poverty” (that is, with incomes below half the poverty line) than any other program.

- SSI, which assists low-income seniors and people with disabilities, lifted 2.9 million people out of poverty.

- Rent subsidies lifted 3.0 million people out of poverty.

- TANF and state General Assistance programs lifted 438,000 people out of poverty. (General Assistance programs are small programs in some states that provide cash assistance benefits typically to a narrow group of adults without children, often those with disabilities.)

- Two tax credits for low- and moderate-income working families — the EITC and the low-income portion of the Child Tax Credit — together lifted 10.6 million people out of poverty, including 5.5 million children. (These figures are based on our analysis of Census data and include both the refundable and non-refundable portions of the Child Tax Credit.)

The programs’ true impact is larger than these figures suggest for several reasons. First, the programs reduced the severity of poverty for tens of millions by lifting them closer to the poverty line. Second, while the SPM provides a more complete picture than the official poverty measure, the data still understate the safety net’s anti-poverty effects because survey respondents often underreport their income from government programs. Household surveys depend on participants’ recollections over many months and typically fail to capture some income; the Census data are no exception. (For example, a CBPP analysis that corrects for underreporting finds that SNAP lifted 8.4 million people out of poverty in 2015, compared with 4.6 million in the uncorrected data.)

Finally, the SPM figures released today also take into account only the immediate impact of added resources for struggling families. But a large body of evidence shows that such resources can help improve children’s chances of growing up healthier, doing better in school, and having higher expected future earnings. (The tax credit figures are slightly conservative for another reason: they only include the low-income portion of the Child Tax Credit.)

Today’s data show that TANF, which provides basic monthly income assistance to families with children, is less effective than the other four programs discussed above at reducing poverty. While SNAP and refundable tax credits have become more effective at reducing poverty and deep poverty over the past two decades, past studies have found TANF does far less to reduce poverty today than Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the cash assistance program that preceded TANF’s creation in 1996. TANF’s weaker effectiveness is due in part to policies that take away basic income assistance from families when a parent doesn’t meet rigid work requirements — policies that the Trump Administration and some in Congress have proposed as a model for other anti-poverty programs — and other policies that often make programs inaccessible to poor families.

The President’s budget would make deep cuts to successful anti-poverty programs. It would cut SNAP, in which benefits now average only $1.40 per person per meal, by about 30 percent. It would also cut funding for the Department of Housing and Urban Development by $9.7 billion, or 18 percent, including eliminating rental vouchers for 140,000 low-income households and raising rents on 4 million other low-income households. The President’s budget would also eliminate the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, and drastically increase the number of uninsured with its proposed repeal of the Affordable Care Act. And the budget proposes to deny the Child Tax Credit to children of many immigrant parents without a Social Security number, the bulk of whom are U.S. citizen children.

While unlikely to be enacted this year or next, the budget proposals reflect where the President would take the country in the years ahead if given the opportunity. And, in several cases, the Administration is seeking to make cuts in these assistance programs — including cuts that Congress has rejected in some cases — through executive actions, such as regulations. These include two proposed SNAP regulations that the Administration itself says would take food assistance from nearly 4 million people, including 755,000 adults who are among the poorest people receiving SNAP. And the recently issued final “public charge” regulation changes how the receipt of public benefits is factored into decisions concerning which prospective immigrants can legally enter the United States and which immigrants here lawfully can adjust their immigration status. Though not yet in effect, the regulation is already creating confusion and fear, leading many individuals in low-income immigrant families to forgo benefits for which they qualify.

In terms of policies that the President and Congress enacted, the 2017 tax law largely left low- and moderate-income families behind. The Child Tax Credit expansion in the law provided no or only token help to millions of poor and low-income children, while the tax law overall delivered windfall gains to wealthy households and profitable corporations, further widening the gap between those at the top and everyone else. The tax law also erodes the EITC by using a slower measure of inflation to adjust tax brackets and other tax provisions each year.