BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker proposes to replace the state’s regressive flat tax system with a graduated rate structure, which would require a voter-approved constitutional amendment in 2020. Known as the “Fair Tax” plan, it’s a wise course correction to the current flat tax system, which falls harder on working people than the wealthy and doesn’t support the state’s financial needs.

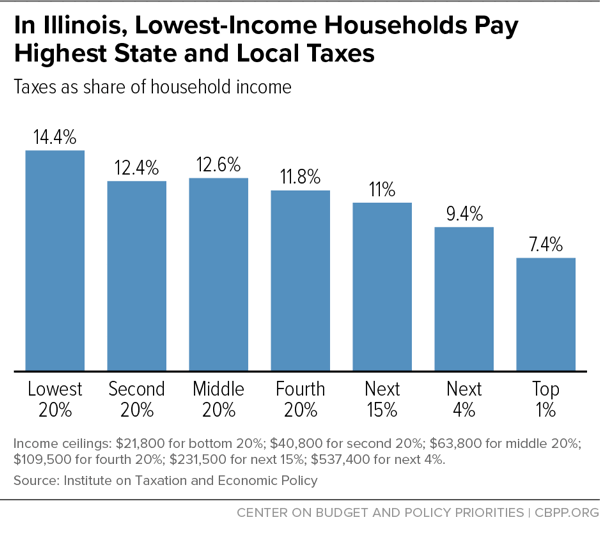

Most states with a personal income tax maintain a progressive structure that taxes higher income at higher rates. This helps balance the other major forms of state and local taxation — sales, property, and excise taxes — which, together, tend to fall hardest on those with the least income.

Illinois, however, is one of eight states with a flat tax; it taxes all income at 4.95 percent, regardless of income level. As a result, middle- and low-income households must bear more of the cost of state services and pay a much higher share of their earnings in state and local taxes overall.

As the chart shows, the bottom fifth of Illinois taxpayers, those making below $21,800, contribute 14.4 percent of their income in state and local taxes each year on average, compared to only 7.4 percent for the top 1 percent, or those with incomes above $537,400. That gives Illinois the third-highest effective rate on low-income families nationwide.

Governor Pritzker’s proposal would swap the flat tax for a graduated structure with six brackets, with rates starting at 4.75 percent on the first $10,000 of income and rising to 4.9 percent on income up to $100,000. From there, the rates increase to 4.95 percent for income between $100,000 and $250,000, 7.75 percent up to $500,000, and 7.85 percent up to $1 million. Once taxpayers reach $1 million a year in earnings, their entire income would be taxed at a flat rate of 7.95 percent; that’s different than other states with so-called “millionaires’ taxes,” where the top rate only applies to income above a certain level.

The plan would also raise the corporate tax rate from the current 7 percent to 7.95 percent, matching the top personal income tax rate. Other components include an expanded property tax credit and a new nonrefundable child tax credit, set at $100 per child for households earning up to $100,000. Only about 3 percent of Illinois taxpayers would see a tax increase under the plan, according to the governor’s office.

Beyond making Illinois’ tax system much fairer, the proposal would raise much-needed revenue and help shore up the state’s damaged finances, which stem in part from a two-year budget impasse that ended in mid-2017. The state faces a $3.2 billion budget deficit and is carrying about $8 billion in debt from unpaid bills and interest, such as backpay for state employees and overdue payments to contractors, health care providers, universities, and small businesses.

The tax revisions could raise about $3.4 billion a year, the administration estimates. That’s a significant infusion that could let Illinois better meet its needs, including core financial obligations like pension and interest payments and essential state services such as education. For example, state lawmakers last year approved a new funding formula for K-12 schools, which will require an extra $350 million a year in state funds.

A graduated income tax would also put Illinois on a much sounder financial trajectory over the long term, since higher rates on higher incomes are an effective way to capture the increasing share of economic benefits flowing to those at the very top. That’s especially true given the plan’s inclusion of a millionaires’ tax. As our recent report explains, targeted rate hikes at the top are a proven way to raise substantial revenues from a small sliver of taxpayers who have done extraordinarily well, without harming state economies.

New revenues from this plan could let Illinois make more ambitious investments in its future, rather than just correcting past mistakes or meeting minimum baseline needs. For example, it could follow the lead of states like California and Minnesota that used new revenues from millionaires’ taxes for big investments in early education and other services. Targeting new state investment to good public schools, high-quality infrastructure, and income-boosting policies like tax credits for families is a proven strategy to expand opportunity and help build a more equitable economy over time.