BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As policymakers debate the scope of the next federal response to COVID-19 and the economic crisis, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected a stronger recovery than it projected in July of 2020 — partly due to previous relief legislation — but highlighted the challenges to a full recovery. Without further fiscal relief, CBO projected, the economy won’t reach its full-capacity potential until 2025. Moreover, economy-wide statistics don’t fully capture the unmet human needs or extraordinary circumstances that COVID-19 created, so they aren’t an adequate guide for a full and robust response.

In a typical recession, fiscal policy aims to stimulate economic activity: when inadequate demand means emptier restaurants or fewer people traveling, fiscal stimulus can help return the economy to its full potential. But in a pandemic, the priority should be to limit the spread of the virus. Before pushing the economy back to its capacity and filling restaurants and airplanes, policymakers should pursue the dual imperatives of stopping the virus and relieving financial hardship. Standard macroeconomic statistics don’t fully measure the resources required to address either challenge, for several reasons:

- Public health funding is needed regardless of economic conditions. President Biden proposes to “mount a national vaccination program, expand testing, mobilize a public health jobs program, and take other necessary steps to build capacity to fight the virus.” None of that would be necessary in an ordinary recession but, given the circumstances, fiscal policy must devote the resources needed to end the pandemic as soon as possible. Further, the most important first step in the economic recovery is to control the virus, as many economists have noted.

- Social distancing reduces the economic impact of each dollar of spending. The amount of economic activity that fiscal policy stimulates hinges on the extent to which people spend any extra income they receive, thereby supporting businesses and their workers. But as CBO explained last fall, while legislation can still “increase economic activity by boosting overall demand, social distancing will temper that increase. When people limit their social interactions, they reduce households’ and businesses’ demand for goods and services.” Thus, current conditions call for more aggressive fiscal policy than usual.

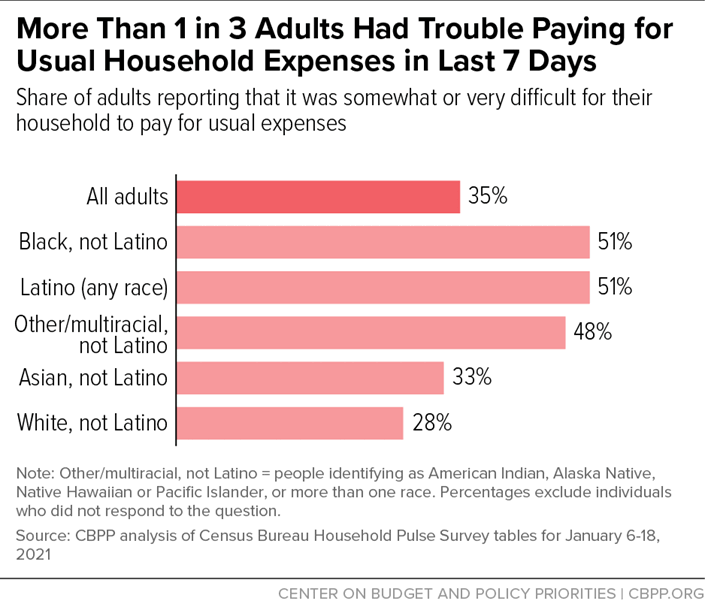

- Economy-wide trends can mask the depth and distribution of hardship. Total economic output can grow even as some households experience severe hardship or lose ground. That’s what has happened during the uneven, “K-shaped” recovery from the pandemic recession.

Today’s hardship remains extraordinary. Some 80 million adults report difficulty covering usual household expenses, the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse figures for January show, which is 35 percent of all adults and includes 51 percent of Black and Latino adults. Fifteen million people aren’t caught up on their rent. Among adults living with children, food hardship remains four times above pre-COVID levels.

The labor market’s improvement stalled in December, having recovered only around half of the 20 million jobs lost due to the pandemic; Black and Latino workers face especially elevated unemployment rates of 9.9 and 9.3 percent, respectively. And over a million workers filed new claims for regular state unemployment insurance or federally funded Pandemic Unemployment Assistance last week, more than in the worst week in the Great Recession of about a decade ago.

December’s relief package, which aided unemployed workers and other financially vulnerable people, is an important reason why CBO’s projections improved, but its expanded unemployment benefits expire in mid-March and its food assistance provisions end this summer.

Some adversity from COVID-19 was inevitable, but further, lasting economic damage isn’t. Timely enactment of an appropriately scaled relief package can avoid the mistakes of the Great Recession, when policymakers didn’t follow up on the 2009 Recovery Act with a big enough further fiscal response, resulting in a slower recovery and greater long-term harm for households and the economy. The burdens of a delayed recovery would likely be largest for Black and Latino workers, who are often “last hired, first fired” and see a sharper increase and slower subsequent decline in unemployment than white workers. In the Great Recession, the drop in Black employment began two months before that for white workers and lasted 15 months longer.

A large relief package might well put some upward pressure on inflation, but the Federal Reserve is well equipped to stabilize prices and manage these risks. Indeed, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said that the Fed would “welcome slightly higher inflation” and that, if faced with “sustained inflation at a level that was uncomfortable, we have tools for that.” The greater risk today is doing too little. As Powell put it, “I’m much more worried about falling short of a complete recovery and losing people’s careers and lives that they built because they don’t get back to work in time. . . . I’m more concerned about that and the damage that will do, not just to their lives but to the United States economy.”

Policymakers should scale the fiscal policy response to stop the spread of the virus, address the persistent hardship affecting millions of people, and ensure a strong and broadly shared economic recovery.