BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The uninsured rate has fallen by more than half for low-income, non-elderly, rural adults in states that expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), says a new report from the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families and the University of North Carolina (UNC) Rural Health Research Program. Coverage gains are much smaller in non-expansion states, the report says. These findings underscore what’s at stake in states like Arkansas, Kentucky, and Michigan, where proposals to take Medicaid coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement would affect large numbers of beneficiaries in rural areas.

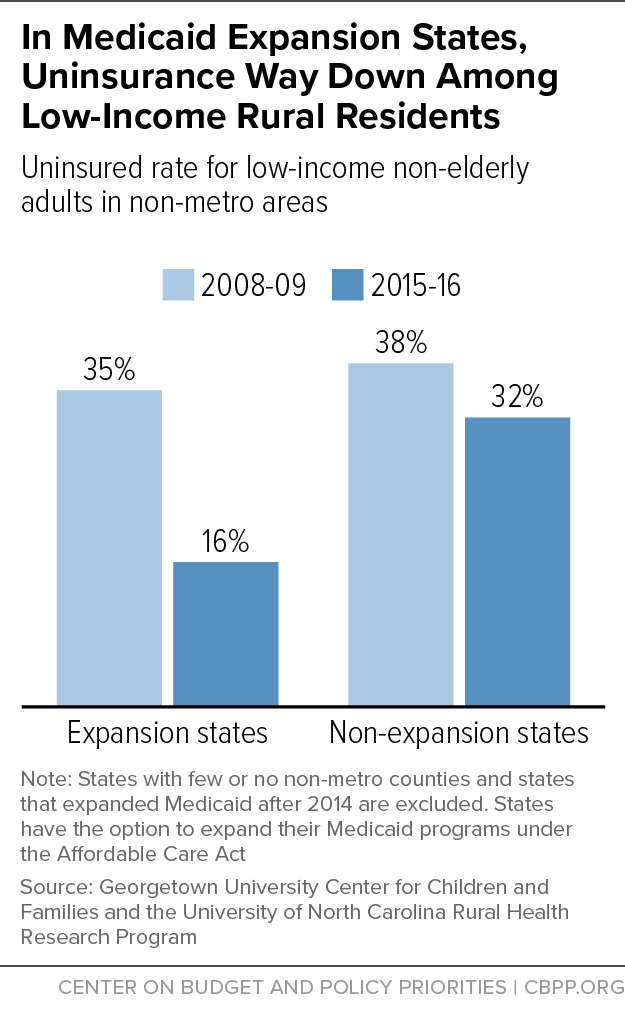

The uninsured rate among non-elderly adults who live in rural areas and would be eligible for Medicaid coverage in expansion states — those with incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line, or about $16,750 a year for an individual — dropped from 35 percent in 2008-09 to 16 percent in 2015-16. (See figure.) In non-expansion states, it dropped only from 38 percent to 32 percent. (The study’s authors used the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to calculate these estimates using two-year time frames to generate more precise estimates.)

These findings reflect the growing gap in coverage between people in expansion states and those in non-expansion states.

Some expansion states have experienced especially large coverage gains among low-income rural residents. In Colorado, Nevada, Kentucky, Oregon, New Mexico, Arkansas, Connecticut, Hawaii, Michigan, and West Virginia, uninsured rates among non-elderly adults in rural areas dropped by more than 20 percentage points. Previously, we estimated that by March 2016, 15 percent, or 1.7 million, of the people who gained coverage nationwide through the Medicaid expansion live in rural areas.

The rural uninsurance rate in the typical non-expansion state is 32 percent, which is double the rate in states that expanded Medicaid when the expansion took effect in 2014. Some non-expansion states are again considering expanding. In November, voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah will consider ballot initiatives to adopt the expansion. These states have rural uninsured rates of 28 percent, 24 percent, and 31 percent, respectively, according to the report.

The report’s findings underscore how rural areas will be hurt in states that have either implemented or are considering proposals to take Medicaid coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement, as discussed in our recent fact sheet. Some of the states with these harmful proposals, like Arkansas, Kentucky, and Michigan, are ones where rural residents have benefitted the most from Medicaid expansion.

Specific economic factors affecting rural areas — for example, higher unemployment and lower labor force participation than non-rural areas — make it likely that large numbers of people will lose coverage because of a work requirement. That includes people who are working: many rural jobs feature variable hours and above-average levels of part-time work, which will make it harder for some workers to meet the 80-hour-per-month requirement that some states want to impose.

People in rural areas also have obstacles to reporting their compliance with work requirements. In Arkansas, for example, Medicaid beneficiaries must demonstrate their compliance using an online portal, even though Internet access is spotty in rural parts of the state — as it is nationwide. That’s likely one reason why over 4,300 Arkansans have already lost their Medicaid coverage due to the state’s work requirement, with thousands more likely to follow.

The Georgetown-UNC report demonstrates that Medicaid expansion is a powerful tool for expanding coverage in rural areas. State policymakers should continue to move in this direction, rather than erect barriers to coverage.