BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Hundreds of Thousands of Virginians Will Gain Coverage from Medicaid Expansion, But Eligibility Restrictions Will Lessen Gains

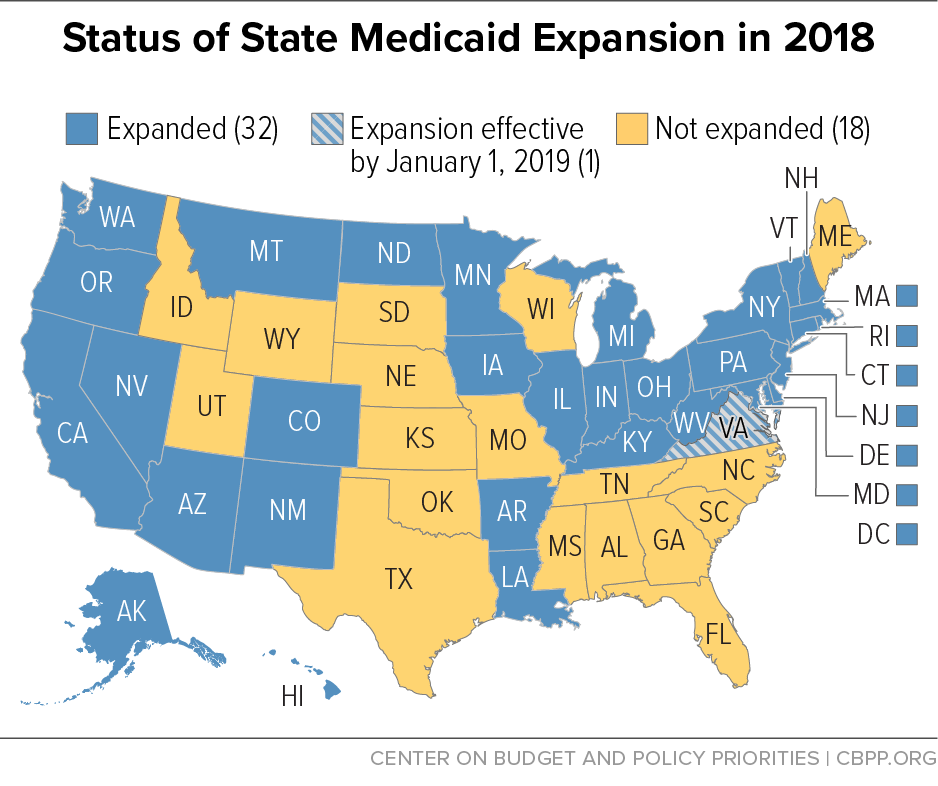

Virginia lawmakers agreed today to adopt the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion by the end of this year, providing health coverage to nearly 400,000 low-income Virginians. Virginia can expect some of the same gains as other states that expanded Medicaid: coverage increases, budget savings, and less uncompensated care for hospitals. Those who gain coverage will likely see better health, more access to care, and greater financial security.

These gains, however, will be more modest than otherwise due to several eligibility restrictions for those gaining eligibility.

The proposal directs Virginia to pursue a federal waiver to impose a rigid work requirement, charge premiums to people with incomes above the poverty line, and take away coverage from people who don’t meet these requirements. Adult beneficiaries under age 65 who receive coverage through the Medicaid expansion will have to work or participate in work-related activities for 80 hours each month or lose their coverage. There are limited exemptions, like for people with disabilities or serious illnesses, pregnant women, and primary caretakers of children or adult dependents.

Taken together, Virginia’s work requirement and premiums policies will create a costly new bureaucracy and cause tens of thousands of Virginians who’d otherwise be eligible for Medicaid to lose their coverage. While estimates aren’t available for the version of the bill passed by the Senate, the state’s Medicaid office expected 18 percent of the expansion population, or 50,000 people, to lose coverage under similar policies adopted earlier by the House of Delegates, while the state’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) expected 33,000 people to lose coverage (compared to full expansion). Kentucky, Michigan, and other Medicaid expansion states implementing or considering work requirements have also forecast large coverage losses.

In addition, Virginia will have to spend more than $20 million a year to administer the work requirement and provide case management and support services to the affected population, JLARC projects. These costs make it less likely that the expansion will create net savings for the state — especially because Virginia will see smaller reductions in uncompensated care costs than it would under an expansion that doesn’t come with eligibility restrictions.

Also, research shows that work requirements likely won’t advance the stated goals of boosting employment and improving the workforce. To the contrary, improving access to Medicaid can itself help develop a healthy and productive workforce. Surveys of Medicaid expansion beneficiaries in Ohio and Michigan found that Medicaid coverage made it easier for them to look for work and stay working. Montana has created a workforce promotion program that targets Medicaid enrollees who are looking for work or better jobs and connects them with services such as career counseling, on-the-job training programs, and subsidized employment, without the harmful and often counterproductive effects of work requirements.

Virginia's decision to expand Medicaid will yield major improvements in coverage, access to care, and health, but these gains could have been greater. For states considering adopting the Medicaid expansion, like Georgia, Kansas, and North Carolina, a straight expansion without eligibility restrictions remains the best way to increase coverage, improve residents’ lives, and protect the state budget.