BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Children in Distress Due to Increased Hardship: An Interview With Dr. Philip A. Fisher

Dr. Philip A. Fisher, Professor of Psychology and Director of the Center for Translational Neuroscience at the University of Oregon, is a national expert on how adverse experiences affect children’s development. Last April he launched the RAPID-EC (Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development-Early Childhood) survey to learn how families were faring during the pandemic. Every two weeks since then, Dr. Fisher and his team have surveyed 1,000 families with children under age 5.

What findings stand out the most for you?

"When parents don’t have enough money to meet their basic needs, we see a sequence of events that can have long-term negative consequences for children."There are two main parts of the story that have presented themselves throughout the survey. First, it is clear to us that financial relief has got to be a top priority because when parents don’t have enough money to meet their basic needs, we see a sequence of events that can have long-term negative consequences for children. The second important finding is that the pandemic has burst the structural inequalities based on race and ethnicity and disability wide open.

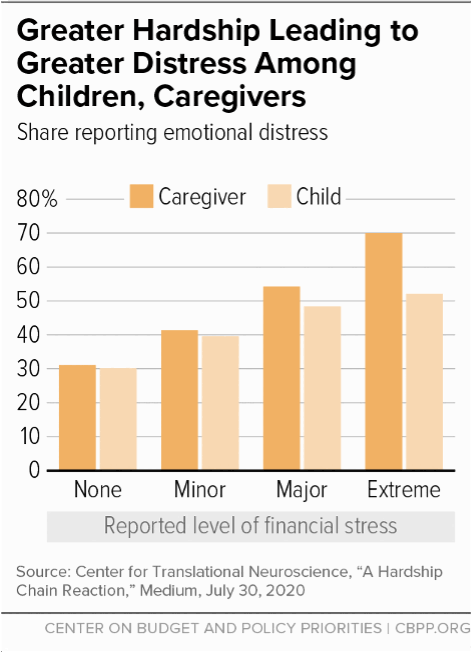

As we’ve followed families over time, we have learned that if you want to know how young children are doing, you can work backward by first assessing how their parents are doing. And how parents are doing is very closely tied to whether they are able to meet their basic needs. If parents report not having enough money to put food on the table or to pay their rent or utilities, that often is followed by reports of increased levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and loneliness. That is followed by parents reporting greater concerns about their children, including greater stress, more acting out, and more fussiness.

"We see higher levels of hardship and stress in Black, Latinx, and single-parent households and in households with a child with a disability."We see the structural inequalities based on race and ethnicity and disability across many issues, including access to child care, whether someone can return to their job, and levels of stress. We see higher levels of hardship and stress in Black, Latinx, and single-parent households and in households with a child with a disability.

Among Black and Latinx families, we have even seen higher levels of hardship and stress among middle- and upper-income families. We think that a number of factors have contributed to that: less wealth, more difficulty getting loans, less secure jobs, and caring for other family members who may not have been faring well before the pandemic and now need more help from family members.

What could alleviate some of the issues you are seeing?

Additional resources to help families meet their basic needs are critical. Prior to the end of the CARES Act funding, we had about 20 percent of families experiencing hardship. When we asked families about whether they would have difficulty meeting their basic needs in the coming month, after the CARES Act funds were scheduled to end, that jumped to 40 percent, which is what we saw when the funds did end.

It is also important to be mindful that although the pandemic has made things worse, many of these families were experiencing difficulties making ends meet prior to the pandemic. One-time payments will help to keep families from going under water further, but they will not suddenly make everything better than it was prior to the pandemic.

What are your greatest fears if we don’t act or don’t act fast enough?

"There is a high risk that the stress children are experiencing will overload their systems and have a long-term impact on their brain and biologic development."The experiences that young children have lived through with the pandemic have created a perfect storm for what we refer to as toxic stress — high levels of stress that have significant and long-term consequences. When children experience high levels of chronic stress, parents can mitigate the long-term negative consequences by providing a protective environment. When parents’ ability to do that is compromised because they are unable to meet their basic needs and are experiencing high levels of stress and anxiety themselves, there is a high risk that the stress children are experiencing will overload their systems and have a long-term impact on their brain and biologic development. We know that toxic stress can not only impact learning, academic achievement, and social skills development but can also lead to greater health issues. To solve these issues, we need a robust, trauma-informed response.

How would you define a robust response?

The first thing we need to do is to recognize the interconnectedness of many of the issues families with young children are facing and develop a holistic response. We need an Early Childhood New Deal. We need to make sure families can meet their basic needs while we simultaneously fix our broken child care system so mothers can return to the labor market. We also need to make sure that child care providers and parents have access to adequate mental health services to address the trauma they have experienced during the pandemic. And we need to address structural inequities to provide greater income and stability for Black and Latinx mothers.

I ultimately am hopeful that we can come out of this better than when we started, but we are starting with systems that are very depleted. Young children are incredibly resilient and there is lots of plasticity in their brains. The task in front of us is to create the conditions that will allow them to thrive as we come out of the pandemic.