BEYOND THE NUMBERS

If the Trump Administration and a group of 18 states convince the Supreme Court to strike down the Affordable Care Act (ACA), its Medicaid expansion — which covers more than 12 million low-income adults across the country — would end along with the rest of the law. That would take health coverage away from millions, reduce access to care, increase premature deaths, and increase medical debt and uncompensated care costs, research shows. It would also exacerbate racial disparities in coverage and access to care, and it would harm children along with adults.

Oral arguments before the Court are scheduled for November 10. The lawsuit, which 18 state attorneys general filed and the Administration later joined, argues that an incidental effect of the 2017 tax law was to repeal the entire ACA — specifically, that when policymakers eliminated the ACA’s tax penalty for not having insurance, the change made the entire ACA unconstitutional. While legal experts almost uniformly dismiss that argument as absurd, the case has made its way to the Supreme Court, raising a real risk that the Court could overturn the law.

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion lets states cover adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line (about $17,600 a year for a single adult), with the federal government paying 90 percent of the cost (well above the regular federal matching rate for Medicaid) and the states paying the rest. Before the ACA, the typical state covered parents only if their incomes were below about two-thirds of the poverty line, and most states didn’t cover non-elderly adults without children no matter how poor they were. If the ACA’s enhanced federal funding disappeared, it’s hard to imagine that states would provide meaningfully more generous coverage today than they did before the ACA — especially if the Court strikes down the law amidst an economic downturn that has fueled a major state budget crisis.

Twelve million people had Medicaid expansion coverage as of mid-2019, and the figure likely is significantly higher now due to the economic downturn: expansion enrollment rose almost 13 percent between February and July in states with available data, equivalent to 1.5 million people nationwide. The overwhelming majority of them would likely become uninsured if the Court strikes down the ACA. Overturning the ACA would also prevent the remaining 14 states that have not yet implemented the expansion from doing so, which could extend Medicaid coverage to over 6 million more people.

A large and growing body of research shows that coverage losses from ending expansion would cause severe harm, including:

- Less access to care. Expansion has increased the share of low-income adults getting primary care, preventive care, mental health care, and treatment for substance use disorders, studies show. It’s been especially important for the large share of expansion enrollees with significant pre-existing conditions, who have seen large increases in access to regular care and in prescriptions filled for conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, and depression.

- More premature deaths. Medicaid expansion saved the lives of at least 19,200 older low-income adults from 2014 to 2017 in states that adopted it, while state decisions not to expand cost the lives of 15,600, according to a careful study by researchers at the University of Michigan, National Institutes of Health, Census Bureau, and UCLA. (Hover on the map below for state-by-state estimates.) Expansion was especially important in preventing premature deaths due to conditions responsive to medical care, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

- More financial insecurity. Studies have found that expansion reduces medical debt, improves households’ access to credit, and reduces evictions, with one study finding that evictions fell about 20 percent in expansion compared to non-expansion states. Ending expansion would likely reverse these improvements. The effects would be especially devastating when millions of people are struggling to afford food, rent, and other necessities due to the economic downturn.

- More uncompensated care. By increasing the number of uninsured, ending expansion would also increase hospitals’ uncompensated care costs. Those costs fell by 45 percent as a share of hospital budgets in expansion states between 2013 and 2017, compared to 2 percent in non-expansion states, recent data show.

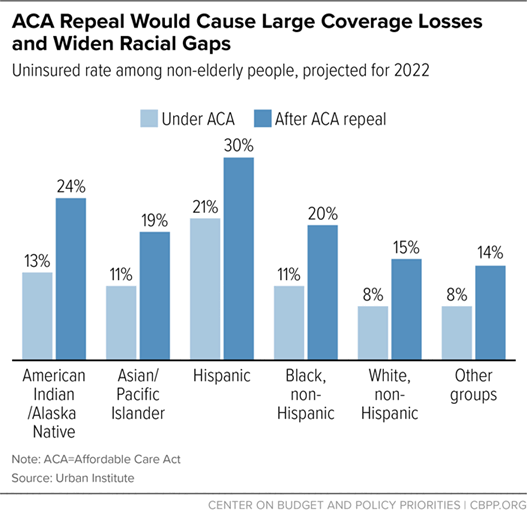

Medicaid expansion has been particularly important in expanding coverage for Black and Hispanic people and American Indians/Alaska Natives, so eliminating it would disproportionately harm those groups. Gaps in access to care have shrunk along with gaps in coverage, and preliminary evidence suggests that expansion has narrowed disparities in health outcomes as well, while improving outcomes for all racial and ethnic groups. For example, a 2018 JAMA study finds big reductions in the share of residents who died from kidney failure in expansion compared to non-expansion states, with larger improvements for Black people (who are at higher risk for kidney failure).

And while ending expansion would directly harm adults, it also would indirectly harm children. Expansion has reduced uninsured rates and increased access to care for new mothers, research shows, almost certainly benefiting their children as well. And a recent study, based on another randomized trial, adds to the large body of evidence that Medicaid-eligible children are likelier to gain coverage when their parents become eligible.

The children’s uninsured rate has risen over the past few years, with over 700,000 more children uninsured than in 2016. Ending expansion would be another major setback, undermining children’s access to care and long-term well-being.

| TABLE 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lives Saved, and Lost, Due to States’ Medicaid Expansion Decisions, Adults Aged 55-64 | ||

| State | Lives at stake over four years | State is Challenging ACA |

| Alabama | 768 | Yes |

| Alaska* | 76 | No |

| Arizona | 808 | Yes |

| Arkansas | 440 | Yes |

| California | 4,448 | No |

| Colorado | 520 | No |

| Connecticut | 304 | No |

| Florida | 2,776 | Yes |

| Georgia | 1,336 | Yes |

| Hawaii | 156 | No |

| Idaho* | 180 | No |

| Illinois | 1,380 | No |

| Indiana* | 796 | Yes |

| Iowa | 272 | No |

| Kansas | 288 | Yes |

| Kentucky | 704 | No |

| Louisiana* | 764 | Yes |

| Maine* | 180 | No |

| Maryland | 528 | No |

| Michigan* | 1,196 | No |

| Minnesota | 460 | No |

| Mississippi | 540 | Yes |

| Missouri** | 776 | Yes |

| Montana* | 132 | No |

| Nebraska* | 152 | Yes |

| Nevada | 356 | No |

| New Hampshire* | 120 | No |

| New Jersey | 828 | No |

| New Mexico | 284 | No |

| North Carolina | 1,400 | No |

| North Dakota | 44 | Yes |

| Ohio | 1,452 | No |

| Oklahoma** | 476 | No |

| Oregon | 484 | No |

| Pennsylvania* | 1,476 | No |

| Rhode Island | 120 | No |

| South Carolina | 788 | Yes |

| South Dakota | 84 | Yes |

| Tennessee | 964 | Yes |

| Texas | 2,920 | Yes |

| Utah* | 216 | Yes |

| Virginia* | 900 | No |

| Washington | 688 | No |

| West Virginia | 348 | Yes |

| Wisconsin | 576 | No |

| Wyoming | 64 | No |

States listed in blue have implemented expansion; states listed in orange have not. Estimates in the study are for lives saved or lost from 2014-2017, but the estimates also approximate lives saved over the first four years of expansion (for states expanding after 2014) and lives that could be saved over the first four years of expansion (for states that have not yet implemented expansion). Table omits the District of Columbia, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont, because they expanded Medicaid prior to 2014 and are therefore excluded from the analysis.

* Some states expanded Medicaid to low-income adults effective after January 1, 2014: Michigan (April 2014), New Hampshire (August 2014), Pennsylvania (January 2015), Indiana (February 2015), Alaska (September 2015), Montana (January 2016), Louisiana (July 2016), Virginia (January 2019), Maine (January 2019), Idaho (January 2020), Utah (implemented full expansion January 2020), and Nebraska (October 2020).

** Estimates for Missouri and Oklahoma are lives lost from 2014 to 2017. These states have adopted Medicaid expansion but have yet to implement it.

Source: CBPP calculations based on Miller et al. supplemental estimates.