WHY THE ESTATE TAX IS NOT "DOUBLE TAXATION"

by Ruth Carlitz and Joel Friedman

PDF of full report If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader.

One of the most enduring myths about the estate tax is that it constitutes “double taxation” — that is, it taxes income that already was taxed under the income tax during the decedent’s lifetime. This claim is seriously distorted:

- 99 percent of estates pay no estate tax at all, primarily because the first $1.5 million of any estate’s value ($3 million for a couple) is entirely exempt from the estate tax. Thus, 99 percent of estates cannot face “double taxation” under the estate tax for the simple reason that they owe no estate tax.

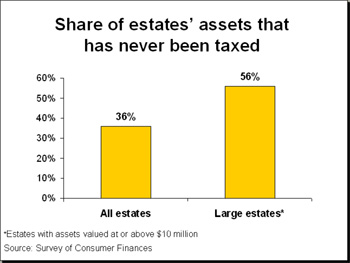

- For those few, large estates that do owe estate taxes, a substantial proportion of their assets have never been taxed. Indeed, the majority of assets in estates valued over $10 million consist of untaxed capital gains — that is, property, stocks, and bonds that have appreciated in value since they were first purchased by the decedent but have never been subject to tax.

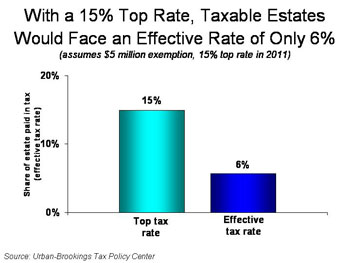

- Given that untaxed capital gains make up a major part of large estates, some have suggested that it would be appropriate to slash the estate tax’s top tax rate to 15 percent, the current capital gains tax rate. That, however, would reduce the share of an estate that is paid in estate taxes — that is, the effective tax rate — to an average of just 6 percent, a mere fraction of the capital gains rate, because of the large exemptions and deductions available for the estate tax.

Much of the Value of Taxable Estates Has Never Been Taxed

Without

the estate tax, capital gains included in an estate would never be taxed.

Under current law, the gain from appreciation of an asset is subject to the

income tax only when the asset is sold. Upon the sale of an asset, the

difference between the purchase price and the sale price is taxed as a capital

gain. If a person holds on to an asset until he or she dies, however, his or

her heirs inherit the asset at its value at the time of the decedent’s

death. The gain on the asset from the time of purchase to the time of

death is never taxed under the income tax.

Without

the estate tax, capital gains included in an estate would never be taxed.

Under current law, the gain from appreciation of an asset is subject to the

income tax only when the asset is sold. Upon the sale of an asset, the

difference between the purchase price and the sale price is taxed as a capital

gain. If a person holds on to an asset until he or she dies, however, his or

her heirs inherit the asset at its value at the time of the decedent’s

death. The gain on the asset from the time of purchase to the time of

death is never taxed under the income tax.

Some of the capital gains income that escapes taxation under the income tax may be taxed under the estate tax. The appreciated value of the asset is included in the estate and, if the estate is large enough, subject to taxation.

Unrealized capital gains make up about 36 percent of the value of all estates and about 56 percent of estates worth more than $10 million, according to estimates by economists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Federal Reserve Board, using Federal Reserve data.[1] Further, as the estate tax exemption level rises over the next several years, only the largest estates — those that tend to have the greatest share of untaxed assets — will pay any estate tax. (Under current law, the exemption level will rise from $1.5 million for an individual and $3 million a couple today to $3.5 million for an individual and $7 million for a couple in 2009.)

Adopting a 15 Percent Rate Would Be Nearly Tantamount to Repealing the Estate Tax

Since

large portions of taxable estates consist of untaxed capital gains, some

estate tax opponents have suggested retaining the tax but reducing its top

rate to 15 percent, the capital gains tax rate. This, however, ignores that

fact that income taxes are levied on all capital gains income, while

the estate tax is applied only to part of an estate’s value. Estate

taxes are due only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds the

exemption level, and this portion is reduced further by allowable deductions

for charitable bequests and state estate taxes.

Since

large portions of taxable estates consist of untaxed capital gains, some

estate tax opponents have suggested retaining the tax but reducing its top

rate to 15 percent, the capital gains tax rate. This, however, ignores that

fact that income taxes are levied on all capital gains income, while

the estate tax is applied only to part of an estate’s value. Estate

taxes are due only on the portion of an estate’s value that exceeds the

exemption level, and this portion is reduced further by allowable deductions

for charitable bequests and state estate taxes.

As a result, the “effective” estate tax rate, or the portion of an estate’s value that actually is paid in estate taxes, is significantly less than the top tax rate. If the top estate tax rate were 15 percent, the average effective rate would be just 6 percent, according to the Tax Policy Center. That is well below the 15 percent tax rate that long-term capital gains face when they are realized

Thus, establishing a common top rate for the estate tax and capital gains would produce quite unequal tax treatment for the two kinds of assets. Moreover, cutting the top estate tax rate to 15 percent would lose 80-90 percent of the revenue that would be lost under full repeal. The so-called 15 percent “compromise” consequently would differ little from full repeal in terms of its effect on the budget.[2]

|

Linking the Estate Tax Rate to the Capital Gains Tax Rate There are indications that supporters of applying the capital gains rate to the estate tax may try to accomplish this goal by linking the estate tax rate directly to the capital gains rate as it is set in statute, rather than by writing a specific tax rate (such as 15 percent, the current capital gains rate) into estate tax law. Under this approach, the estate tax rate would change automatically each time the capital gains rate changes. One effect of this approach would be to make linking the estate tax rate to the capital gains rate appear less costly than it likely would be. Under the tax-cut bill passed in 2003, the 15 percent rate on capital gains will expire at the end of 2008, at which point the rate will revert to 20 percent. The changes to the estate tax under discussion are primarily intended to address the years after 2009, when this higher capital gains rate is scheduled to apply. Thus, when the Joint Committee on Taxation calculates the official cost of applying the capital gains rate to the estate tax, it would be required to assume that the capital gains rate would be 20 percent, even though there appears to be considerable support to extend the 15 percent rate past 2008. (Indeed, Congressional action to extend the 15 percent rate may occur as soon as this fall.) This assumption of a 20 percent rate would artificially lower Joint Tax’s estimate of the cost of this proposal. In addition, linking the estate tax rate directly to the capital gains rate as it is set in statute would create a backdoor channel for future changes to the estate tax. Once the estate tax is linked directly to the capital gains rate, changes in the capital gains rate will have a direct impact not only on capital gains revenues but also on estate tax revenues. Reducing or eliminating taxation of capital gains, which could be advanced as part of “tax reform,” would reduce or eliminate the estate tax itself. |

The estate tax is an important component of the federal income tax system. Given the prevalence of untaxed capital gains in large estates, the estate tax serves as a backstop to the income tax, providing a way to tax income that otherwise would avoid taxation altogether. The money it raises funds essential programs, from health care to education to defense. If the estate tax were repealed — or retained but drastically altered in a way that loses nearly as much revenue as repeal — millions of Americans ultimately would have to pay the price, in the form of higher taxes or cuts in services.

[1] James M. Poterba and Scott Weisbenner, “The Distributional Burden of Taxing Estates and Unrealized Capital Gains at Death,” Rethinking Estate and Gift Taxation, William G. Gale, James R. Hines, Jr., and Joel Slemrod, eds. Brookings Institution, 2001.

[2] Extending estate tax repeal for an additional ten years (fiscal years 2012 to 2021) would cost nearly $1 trillion in lost revenues and added interest costs. See Joel Friedman, “Estate Tax ‘Compromise’ May Differ Little from Permanent Repeal,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 20, 2005.