Nearly 95 Percent of Low-Income

Uninsured Children

Now Are Eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP

Measures Need to Increase EnrollmentAmong Eligible But Uninsured

Children

by Matthew

Broaddus and Leighton Ku

| View PDF version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

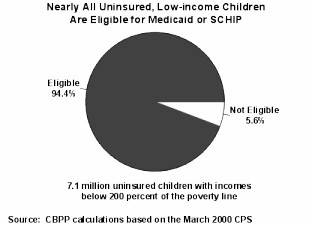

Due to recent expansions in Medicaid coverage for children and state health insurance programs for children, the overwhelming majority of low-income children in the United States now are eligible for health insurance. A new analysis of Census data, presented here, finds that 94 percent of all uninsured children with family incomes below twice the poverty line — currently $28,300 for a family of three — qualify for Medicaid or a separate state child health insurance program supported by SCHIP funds. (SCHIP stands for the State Children's Health Insurance Program, established under legislation enacted in 1997.)

- In 1999, there were 7.1 million low-income uninsured children in the

country. ("Low-income" is defined here as having family income below twice the

poverty line.)

- Some 6.7 million of these children were eligible for child health insurance using the state eligibility standards now in place.

Some progress in reaching uninsured low-income children is being made. The number of children covered through programs supported with SCHIP funds more than doubled in 1999, reaching 1.8 million in December 1999. (This figure reflects increases in both Medicaid and separate state child health insurance programs; states may use SCHIP funds to expand Medicaid or to establish or expand separate children's insurance programs.) In addition, the total number of uninsured children in the United States fell by more than one million between 1998 and 1999, in part because of increased enrollment of low-income children in publicly funded programs. Further progress is likely to have been made in 2000, with some states intensifying outreach efforts and simplifying application and enrollment processes. Nevertheless, the number of uninsured low-income children remains large.

The finding that 94 percent of uninsured low-income children are eligible for Medicaid or a state children's health insurance program demonstrates that the nation has largely solved the problem of making low-income children eligible for health insurance, with the notable exception of certain immigrant children. But we now face the challenge of raising enrollment rates among children who are eligible for coverage but remain unenrolled and uninsured.

Many eligible low-income children apparently have not enrolled because of administrative or other barriers. The findings of this report suggest the federal government and the states need to take additional steps to implement simpler, more-effective enrollment procedures. If the opportunity that the eligibility expansions has created is to be realized more fully, low-income families — especially working families — will need both to be more aware of their children's eligibility for health insurance programs and to be able to enroll their children without facing the burdensome and time-consuming paperwork and office-visit requirements that low-income working parents can encounter.

Since SCHIP's creation in 1997, states have substantially expanded eligibility for children's health insurance. States can use SCHIP funds to increase their Medicaid income eligibility limits, establish a separate insurance program for children whose families have incomes modestly above the state's Medicaid income limit, or pursue a combination of both approaches. Many states have undertaken major efforts to expand eligibility for low-income children and to enroll more of these children. Nevertheless, Census data show that 7.1 million children with annual incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line remained uninsured in 1999 and that approximately 6.7 million of these children are now eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program. An additional 3.5 million uninsured children live in families with incomes exceeding 200 percent of the poverty line, bringing the total number of uninsured children to 10.6 million. In other words, 6.7 million of the 10.6 million uninsured children in the United States — 63 percent of them — are low-income children who are eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program but are not enrolled.

The Census data show there has been progress in recent years in increasing insurance coverage among children with incomes between 100 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line but that coverage has deteriorated among children below 100 percent of the poverty line. Among poor children, Medicaid coverage has fallen since 1995, the year before the federal welfare law was enacted, and the proportion of children who are uninsured has increased. This drop is largely a result of the sharp reductions in welfare caseloads and the ensuing problems in assuring that low-income children and families leaving welfare retain the insurance coverage for which they qualify.

At both the national and state levels, simple, relatively inexpensive measures could be adopted that would help state agencies ease administrative barriers to enrollment and improve administrative processes so low-income families find it easier to enroll their children. The box on the next page describes several such measures currently before Congress. Several additional steps that states can take to lessen these barriers are discussed later in this report.

| Measures Before Congress that Could

Increase Enrollment by Eligible Children In September 2000, the House Commerce Committee approved legislation that contained two measures designed to increase enrollment by eligible children and a third measure designed to address a gap in coverage among low-income children. These three measures were included in Medicare "give-back" legislation that the Commerce Committee passed to restore some of the reductions in reimbursement payments to Medicare providers that resulted from the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. When the full House subsequently took up and passed Medicare "give-back" legislation in October 2000, however, these three policies to boost insurance among low-income children were not included. The three measures still could be restored before the Medicare legislation is enacted. The three measures are as follows: Accord states the option to allow schools and certain other organizations to determine "presumptive eligibility" for Medicaid for low-income children. Recent research shows that a large majority of uninsured low-income children participate in programs such as the free and reduced-price school lunch program. Accordingly, states could be allowed to authorize schools to enroll low-income children in Medicaid for a temporary period, using "presumptive eligibility." Under the presumptive eligibility approach, a child who appears eligible for Medicaid can be enrolled in it immediately and remain enrolled while a regular Medicaid application for the child is processed. The child’s parent is informed that the child appears eligible for Medicaid and that the parent needs to apply for ongoing coverage for the child during the temporary enrollment period. School staff could be trained in how to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations and how to carry out the necessary follow-up activities. In addition to helping school children gain better access to health care and prevention services, presumptive eligibility may yield educational benefits; recent research suggests that children who are insured have fewer sick days and miss school less often than children who lack health insurance. Make it easier for "welfare to work" families to retain their health insurance. Roughly one-quarter to one-third of children in families that leave welfare become uninsured because they do not retain Medicaid coverage and do not get employer-based coverage. This has contributed to an erosion of health insurance coverage among children below the poverty line. Congress established "transitional Medicaid" over a decade ago to maintain a family’s Medicaid coverage for up to one year after the family works its way off welfare, but complicated administrative requirements make it difficult for many families to remain enrolled during this one-year period. Provisions that the House Commerce Committee approved would accord states an option to simplify the rules for transitional Medicaid in ways that should boost enrollment in it. Allow states to restore coverage to legal immigrant children and pregnant women. The Commerce Committee legislation would accord states the option of providing Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility to low-income, legal-immigrant children and pregnant women who entered the United States on or after August 22, 1996, and have been in the country for at least two years. A broader proposal supported by a number of members of both parties and the Clinton Administration would give states the option of providing Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility to these legal immigrant children and pregnant women without a two-year waiting period. Medicaid coverage of low-income immigrant children has contracted since enactment of the federal welfare law. In addition, low-income citizen children in immigrant families have become uninsured to an increased degree as an unintended consequence of the welfare law, even though they remain eligible. The total federal cost of these three provisions would be less than $2 billion over five years ($0.5 billion for presumptive eligibility, $0.5 billion for the transitional Medicaid provisions and $0.6 billion for the immigrant provision with no waiting period). This amount equals less than one-tenth of the $21.5 billion over five years in Medicaid savings contained in the Medicare give-back legislation the House passed. (The savings come from closing a loophole in Medicaid financing arrangements that some states have been using to secure additional federal Medicaid funds.) |

Nearly All Uninsured, Low-Income Children Now Are Eligible for Coverage

The State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), enacted in August 1997, provides

nearly $40 billion over a ten-year period for states to use to expand publicly-funded

health insurance coverage for children in low-income working families. States can use

their share of federal SCHIP funds to expand coverage for children through Medicaid, to

establish orexpand separate child health insurance programs, or to use a combination of

both approaches.(1) States generally can use their SCHIP

funds to provide coverage to children not already eligible for Medicaid who live in

families with incomes up to 200 percent of the poverty line. In some cases, states provide

coverage to uninsured children at income levels above 200 percent of the poverty line.

The State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), enacted in August 1997, provides

nearly $40 billion over a ten-year period for states to use to expand publicly-funded

health insurance coverage for children in low-income working families. States can use

their share of federal SCHIP funds to expand coverage for children through Medicaid, to

establish orexpand separate child health insurance programs, or to use a combination of

both approaches.(1) States generally can use their SCHIP

funds to provide coverage to children not already eligible for Medicaid who live in

families with incomes up to 200 percent of the poverty line. In some cases, states provide

coverage to uninsured children at income levels above 200 percent of the poverty line.

States have embraced the opportunity that SCHIP has provided to expand coverage for low-income children: all 50 states and the District of Columbia are using some or all of their SCHIP funds, and many have adopted major eligibility expansions and launched aggressive outreach efforts. As a result of these state efforts, nearly all uninsured children living below 200 percent of the poverty line now are eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program.

- Census data indicate that in 1999, there were 7.1 million uninsured children under age 19 with family incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line.

- Of these 7.1 million uninsured low-income children, some 6.7 million — or 94 percent of them — would have met their state's eligibility criteria under the Medicaid and SCHIP rules that states were using as of July 2000.

- The 6.7 million uninsured low-income children who are eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program constitute 63 percent of the 10.6 million children at all income levels who lack health insurance, or five of every eight such children. (An additional 400,000 uninsured children with incomes over 200 percent of poverty are eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP, so that 67 percent of all uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid or SCHIP.)

- Most states extend coverage to uninsured children under age 19 with family incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line. Seventeen states set lower income or age standards, which is the primary reason that six percent of low-income children are not eligible. A number of low-income children also are ineligible because of their immigration status.

- In comparison, prior to enactment of SCHIP, eligibility for children's health insurance was much narrower. In the summer of 1996, only seven states had income standards exceeding 133 percent of the poverty line for children aged one to six. Only nine states had income limits above 100 percent of poverty line for children six to thirteen. The majority of states had income limits well below the poverty line for children fourteen and older.

In developing the estimates presented here, we accounted for each state's income eligibility rules (except for policies concerning income disregards) and the presence in several states of state-funded coverage to serve legal immigrant children who entered the country after August 1996. While there are a few factors our estimates could not account for, the effects of these factors are small and tend to balance each other out.(2)

As is discussed below, the number of low-income children covered by Medicaid and SCHIP probably continued to climb in 2000. It seems likely that the number of low-income children without insurance has fallen somewhat this year, compared to the 1999 data presented here. While the situation has probably improved, however, there can be little doubt that there continue to be millions of uninsured low-income children who are eligible for public child health insurance but are not enrolled.

Coverage Trends for Low-income Children

Enrollment in SCHIP has grown rapidly since the program began operation in fiscal year 1998. State programs funded with SCHIP dollars are relatively new, and many of these programs have yet to attain their full enrollment levels. For example, Texas' primary SCHIP program was not implemented until May 2000. Data from the states indicate that the number of children served by SCHIP (either through a component of a state Medicaid program that receives SCHIP funds or through a separate state child health insurance program) more than doubled between December 1998 and December 1999, growing to 1.8 million.(3) There are no recent data on the number of children enrolled in Medicaid nationally, but it seems plausible that child enrollment in Medicaid, as well, increased in 1999.(4) While enrollment data for 2000 are not yet available, it seems likely that enrollment in these programs continued to grow during the past year. In the past few years, combined Medicaid and SCHIP coverage has been expanding among near-poor children but declining among children below the poverty line (see Table 1). Between 1995 and 1999, the proportion of children below 100 percent of the poverty line who had Medicaid or SCHIP-funded coverage fell from 62.1 percent to 55.6 percent. The proportion of poor children who lack any form of health insurance rose during this period from 22.9 percent to 25.8 percent. Insurance coverage among poor children did improve slightly between 1998 and 1999,(5) but the gain was insufficient to erase the declines that occurred from 1995 to 1998.

Near-poor children — those with incomes between 100 percent and 200 percent of the poverty line — fared better. The percentage of such children with Medicaid or SCHIP-funded coverage increased from 25.5 percent in 1995 to 27.4 percent in 1999, while the proportion without insurance dropped from 22 percent to 20.6 percent. The proportions of poor and near-poor children who were uninsured were similar in 1995; by 1999, the proportion lacking insurance was larger among poor children than among the near-poor, who lack any form of health insurance rose during this period from 22.9 percent to 25.8 percent.

In other words, coverage has expanded among near-poor children because of the SCHIP expansions but eroded among poor children in the aftermath of the welfare law. Many poor children eligible for Medicaid are uninsured because their families ceased being enrolled in the Medicaid program when their parents moved from welfare to work.

Health Insurance Trends Among Poor and Near-Poor Children, 1995-1999 |

|||

1995 |

1999 |

Percentage Point Change, 1995-99 |

|

Poor children

(below 100% of poverty)

|

22.9% |

25.8% |

2.9%* -6.5%* |

| Near-poor

children (100 to 200% of poverty) Uninsured |

22.0% |

20.6% |

-1.4%* 1.9%* |

| *

Difference is statistically significant with 95% or better confidence. Source: CBPP analyses of Current Population Surveys, March 1996 and 2000 a Data from the Urban Institute’s National Survey of American Families show a similar trend from 1997 to 1999, with the proportion of poor children who are uninsured rising because of loss of Medicaid, while the proportion of near-poor children without insurance decreased as Medicaid/SCHIP coverage expanded among this group. Some of these trends, however, were not statistically significant. See Genevieve Kenney, Lisa Dubay, and Jennifer Haley, "Snapshots of America’s Families II: Health Insurance, Access and Health Status of Children," The Urban Institute, October 2000. |

|||

Next Steps

As this analysis shows, significant numbers of low-income children lack health insurance not because they are ineligible for coverage but because they are not enrolled in programs for which they qualify. To reduce the number of uninsured children — and to enhance the effectiveness of recent state eligibility expansions — states will need to strengthen efforts to reach out to children eligible for Medicaid and SCHIP-funded programs and make it easier to enroll these children. Both the federal government and states have a role to play to assure that the significant eligibility expansions of recent years translate into substantially greater numbers of children receiving coverage.

Federal Legislation Options

The federal government could give states additional tools to enroll more of the eligible children. In late September, the House Commerce Committee approved two provisions on a bipartisan basis that would assist states in this regard and incorporated these provisions into Medicare "give-back" legislation. These Commerce Committee provisions were not included, however, in the version of the Medicare give-back legislation the House leadership subsequently brought to the House floor. President Clinton has said he would veto that version of the give-back bill. Congress may reconsider the Medicare give-back legislation in the lame-duck session that began this week. The two Commerce Committee provisions are as follows:

1. Accord states new flexibility to enhance the effectiveness of the "presumptive eligibility" option. Under current law, states may allow certain hospitals and community health centers, WIC clinics, Head Start centers, and other "qualified entities" to make a determination that children who appear to meet the Medicaid income guidelines are "presumptively eligible" for Medicaid and to enroll the children in Medicaid for a temporary period. These children must file an application for regular Medicaid coverage within a specified period of time. During the "presumptive eligibility" period, while their applications for regular Medicaid coverage are being processed, the children have Medicaid coverage.

This option could be made more effective by giving states the option to authorize additional types of organizations — most notably schools, which serve millions of low-income children in school lunch and breakfast programs — to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations and thereby play a more active role in outreach.(6) The use of school lunch programs could be particularly helpful since many uninsured children participate in these programs. An Urban Institute study, based on data from the National Survey of American Families, found that in 1997, about four million low-income children receiving free or reduced-price meals through the National School Lunch Program were uninsured. The study also found that 75 percent of all uninsured, low-income children between the ages of 6 and 11 — and 65 percent of all uninsured, low-income children aged 12 to 17 — participate in the school meals programs or have a sibling who does.(7)

Children who receive free or reduced-price school meals have already been certified by school officials as being low-income. Nearly all of them are eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program. If states could more readily use schools to help identify uninsured low-income children, make a determination that these children are presumptively eligible for Medicaid, and connect them with the Medicaid application process during the presumptive eligibility period, significant progress might be made in reducing the ranks of uninsured children.

(Note: A provision of federal law enacted in May 2000 eased rules relating to the sharing of eligibility information between school meals programs and the state agencies that administer Medicaid. This should help facilitate identification of and outreach to more uninsured low-income children, but the process could be made considerably more effective if states could authorize schools to make presumptive eligibility determinations. States could ensure that school officials are trained in how to review cases to determine presumptive eligibility and how to follow up with parents and Medicaid officials to ensure that a "regular" application is completed and processed during the presumptive eligibility period.)

Such a step might yield educational benefits as well. Recent research suggests that school children with health insurance miss school due to illness less than uninsured children and have better school attendance.(8)

Higher rates of insurance among low-income schoolchildren also might help some schools financially. State and local public school funding formulae often are based on the number of children attending school, so higher attendance levels would tend to boost a school's funding level. In addition, because presumptive eligibility can expedite enrollment in Medicaid, it can help assure that school health clinics earn a higher level of Medicaid reimbursement.

In commenting on the linkage between health care and education, a recent National Governors' Association report states: "Policymakers need to focus on eliminating the barriers that affect low-performing students' readiness to learn. Among these barriers are physical and mental health conditions that impact students' school attendance and their ability to pay attention in class."(9) According states the option to authorize schools and similar organizations to conduct presumptive eligibility determinations for Medicaid is a step that policymakers could take to provide more low-income children with access to health care and make the children likely to benefit to a greater degree from their education.

2. Making it easier for families to retain Medicaid when they leave welfare for work. One reason that states have not made more progress in enrolling children in recent years is that large numbers of children have lost coverage after their families have left welfare for low-paid work. Data from state and national studies of families that have left welfare indicate that one-quarter to one-third of the children in such families become uninsured within a year after their families cease receiving welfare assistance.(10) This occurs even though the overwhelming majority of these children remain eligible for coverage. Further, the Census data cited earlier in this paper show that Medicaid coverage of children living below the poverty line has fallen since the welfare law was enacted.

Federal policy has sought for some time to prevent families from losing health care coverage when they move from welfare to work. To help relieve this problem, Congress created the "transitional Medicaid" program, expanded it under the 1988 Family Support Act and renewed it as part of the 1996 welfare law. Families that otherwise would lose their Medicaid coverage due to an increase in their earnings are eligible to receive up to 12 months of transitional coverage.

Unfortunately, transitional Medicaid is complex and cumbersome for both working-poor families and states. Federal rules governing the program make it difficult for many families to retain coverage for the full 12-month transitional period. For example, participating families must file detailed reports on their income and child care expenses in the 4th, 7th and 10th months after leaving welfare to retain transitional Medicaid coverage. There are no comparable requirements for such frequent reports anywhere else in the Medicaid statute.

To make it easier for states to assure that families going to work retain their Medicaid coverage, Congress could give states the option to eliminate the federal reporting requirements that relate to transitional Medicaid and let states guarantee up to 12 months of continuous transitional Medicaid coverage to families that qualify for such coverage as a result of going to work (or increasing their earnings). The House Commerce Committee version of the Medicare give-back legislation included such a provision.

Allowing states to simplify the rules for transitional Medicaid would help assure that low-income children and families do not unnecessarily lose insurance when they go to work. This could help stem some of the erosion of Medicaid coverage that has occurred among children below the poverty line and help reduce the proportion of low-income children who are uninsured.

Coverage for Legal Immigrant Children

A large percentage of legal immigrant children are uninsured. The proportion of such children who lack insurance has risen since the welfare law restricted the eligibility of these children for health insurance.(11) Research also demonstrates that many children who are U.S. citizens but have immigrant parents have lost Medicaid coverage, in part because of confusion about who is eligible and who is not.

The Medicare give-back legislation the Commerce Committee approved in September would have allowed states to ease, although not to eliminate, the welfare law's restrictions on the provision of health insurance to legal-immigrant children and pregnant women who enter the United States on or after August 22, 1996. Under the provision the Committee passed, states would have the option to make these women and children eligible for coverage after they have been in the United States for two years.

A number of Members of Congress of both parties, as well as the Clinton Administration, have proposed going farther and giving states the option of lifting altogether the restrictions on the provision of health insurance to these legal-immigrant children and pregnant women under Medicaid and SCHIP. If such an option were approved and states elected the option, that could yield an additional dividend — by making Medicaid and SCHIP eligibility less confusing for immigrant families, the reform would likely lead to an increase in enrollment in Medicaid and SCHIP-programs among citizen children in low-income immigrant families. These children already are eligible, but many of them are unenrolled and uninsured.

According states the option to cover these legal-immigrant children and pregnant women also could help states and health care providers. If immigrants need health care, they generally turn to public hospitals and clinics for care, adding to state and local uncompensated care burdens. A recent report indicates that New York City hospitals in high-immigrant areas have lost Medicaid revenues and become more indebted since the federal immigrant restrictions took effect.(12) This is particularly pertinent in the context of the Medicare give-back legislation, which seeks to restore some funding to health care providers and to help stabilize providers that have encountered financial difficulties related to changes in federal policies.

Potential State Policy Improvements

Nearly all states have taken steps in recent years to improve their child health outreach efforts. A significant number of states have adopted ambitious campaigns to simplify application procedures and enroll more children. Nevertheless, most states could do more to improve outreach and enrollment practices.(13) Under current federal law, states have an array of options to conduct outreach and increase children's enrollment in Medicaid and SCHIP-funded programs, including the following:

Simplifying application and redetermination procedures. States can redesign application and redetermination forms so they are more user-friendly. States can make sure the questions on the forms are clear, can pare unnecessary questions, and can reduce verification burdens on families seeking to apply for or maintain their children's coverage. Examples of ways to simplify the application and redetermination processes that are permissible under current federal rules include dropping face-to-face interview requirements, allowing applications and redetermination forms to be mailed in, dispensing with or greatly simplifying asset tests, and instituting presumptive eligibility and 12-month continuous eligibility for children, both of which are state options. (Under 12-month continuous eligibility, states may certify a child for Medicaid or SCHIP for a 12-month period, eliminating the need for an application for the second six month period and other cumbersome reporting requirements.)

- Making Medicaid and state SCHIP eligibility policies and procedures more similar. As part of their separate SCHIP programs, many states have developed innovative methods to simplify eligibility criteria, reduce stigma, and make it easier for working families to apply for their children, but some states have not made corresponding changes in their Medicaid programs for children. Doing so should increase enrollment in Medicaid among children from working poor families. For example, if a state uses mail-in applications or has eliminated its asset test for SCHIP, it could make corresponding changes in its Medicaid program.

- Expanding application sites. States can outstation eligibility workers in settings such as clinics and hospitals to help sign up eligible children. They also can provide grants to community-based organizations to help complete applications; this may be particularly useful in minority, ethnic or rural communities that may have less-than-adequate access to eligibility offices.

- Using school lunch information to identify eligible children in need of coverage. As noted earlier, large numbers of uninsured low-income children might gain coverage if Medicaid and SCHIP agencies coordinated efforts with school lunch programs. This approach has the potential to reach millions of uninsured low-income children who already have been determined to have low incomes. Even without the enactment of federal legislation allowing states to let schools make "presumptive eligibility" determinations for Medicaid, there is much that schools and Medicaid and SCHIP agencies can do to use data on children who qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches to identify and reach low-income children eligible for Medicaid and separate SCHIP-funded programs.

- Expanding eligibility for low-income parents. Recent research indicates that state expansions of Medicaid eligibility for parents lead to increased Medicaid participation rates among eligible children.(14) In addition to offering coverage to uninsured low-income parents, state efforts to expand eligibility to these parents thus may reduce the number of uninsured children. Current federal rules for Medicaid and SCHIP offer a variety of options to states to expand eligibility for low-income parents and families, using federal waivers or rules for using "less restrictive" methods of counting income. In recent years, about one-third of the states have adopted eligibility expansions of this nature for parents. In addition, the Health Care Financing Administration recently released guidance enabling states, under certain circumstances, to secure federal waivers that allow them to use a portion of their unspent SCHIP funds to expand coverage for parents.(15)

By expanding eligibility standards for Medicaid and SCHIP-funded programs, states have made most uninsured low-income children eligible for health insurance. Millions of eligible children remain uninsured, however, largely because of administrative barriers to Medicaid and SCHIP enrollment. Congress and the states need to do more to facilitate enrollment in child health insurance programs by streamlining and simplifying the process of enrolling children and families, as well as by closing the eligibility gap for low-income legal immigrant children who have recently entered the United States.

End Notes:

1. Through SCHIP, states receive federal funding at an "enhanced" federal matching rate (i.e., at a higher matching rate than the regular Medicaid program provides) to expand coverage for children. SCHIP funds cover between 65 and 85 percent of a state's cost in expanding coverage for children, depending on the state.

2. Three factors are not accounted for: income disregards, asset tests and specific immigration status. Many states use income disregards, like earnings or child care disregards, to determine whether a child meets the state's income limit for Medicaid or a separate state child health insurance program. If we accounted for disregards, more of the uninsured children would be found to be eligible for Medicaid or a separate SCHIP-funded program. (Some of these children would have gross incomes above 200 percent of the poverty line, the level we used to define whether a child is "low-income." Those children would be not be counted in this analysis as low-income children.) On the other hand, three states — Arkansas, Idaho and Oregon — have asset tests that reduce the number of eligible children. (Six other states — Colorado, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Texas and Utah — have asset tests in Medicaid but not in SCHIP, so low-income children who do not qualify for Medicaid because of their state's asset rules qualify for the SCHIP-funded program.) Accounting for the asset tests in the three states would slightly reduce the number of eligible children. Finally, our estimates of the number of eligible noncitizen children do not account for whether the child is undocumented (and would be ineligible even if he or she arrived before August 1996) or is a refugee (and would be eligible even if he or she arrived after August 1996). Overall, these various factors tend to balance out.

3. Eileen Ellis, Vernon Smith, and David Rousseau, Medicaid Enrollment in 50 States, Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2000. Available at http://www.kff.org.

4. Ellis, et al., collected data on Medicaid enrollments in 1999, but some states did not have data on changes in Medicaid child caseload levels. Among those states that could report these data, the general trend is one of some growth in 1999 in the number of children served. Data from the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey also do not enable us to ascertain the change in 1999 in Medicaid enrollment among children, since these data blend Medicaid and SCHIP caseloads together. The CPS data provide information on changes in the total number of children served by the two programs, but not on the changes in enrollment in each program.

5. Robert Mills, "Health Insurance Coverage: 1999," Current Population Reports, P60-211, September 2000; Jocelyn Guyer, "Uninsured Rate of Poor Children Declines, But Remains Above Pre-Welfare Reform Levels," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 2000 (soon to be revised).

6. Under current law, states could let a limited number of schools conduct presumptive eligibility, but only if they already are considered Medicaid providers, e.g., have a school clinic.

7. Genevieve Kenney, Jennifer Haley, and Frank Ullman, "Most Uninsured Children are in Families Served by Government Programs," The Urban Institute, December 1999.

8. Having either Medicaid or private insurance was associated with fewer school-loss days or restricted-activity days, even after controlling for factors such as income, parental education, and location. Kristine Lykens and Paul Jargowsky, "Medicaid Matters: Children's Health and the Medicaid Eligibility Expansions, 1986-1991," Working Paper 00-01, University of Texas at Dallas, February 2000.

9. Mark Oullette, "Improving Academic Performance by Meeting Student Health Needs,", National Governors' Association Center for Best Practices, October 13, 2000.

10. Jocelyn Guyer, "Health Care After Welfare: An Update of Findings from State-Level Leaver Studies," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 2000. Bowen Garrett and John Holahan, "Health Insurance Coverage After Welfare," Health Affairs, 19(1):175-84, Jan./Feb. 2000.

11. Leighton Ku and Shannon Blaney, "Health Coverage for Legal Immigrant Children: New Census Data Highlight Importance of Restoring Medicaid and SCHIP Coverage," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 10, 2000.

12. New York Immigration Coalition, "Welfare Reform and Health Care: The Wrong Prescription for Immigrants," New York City, Nov. 2000.

13. For a discussion of methods to simplify the application and enrollment process for children, see Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, Making It Simple: Medicaid for Children and CHIP Income Eligibility Guidelines and Enrollment Procedures, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2000. In addition, contact Donna Cohen Ross at (202) 408-1080 for information about the Start Healthy, Stay Healthy campaign, a national outreach effort designed to help enroll eligible children in Medicaid and SCHIP-funded programs.

14. Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, "The Importance of Family-based Insurance Expansions: New Research Findings about State Health Reforms," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Sept. 5, 2000.

15. Dear State Health Official letter, signed by Timothy Westmoreland, Health Care Financing Administration, July 31, 2000. This can be found at www.hcfa.gov/init/cn73100.htm.