How Much of the Enlarged Surplus Is Available

for Tax and Program Initiatives?

Available Funds Should be Devoted to Real National Priorities

by James Horney and

Robert Greenstein

|

Fuller Version of this Analysis Available This analysis is a short version of a fuller Center report on this issue. The full report, which has the same title and includes a more extensive discussion of what the authors view as the priorities for use of the available surplus funds. This short version is also available in a PDF format. A brief description of how this analysis applies in the case of the CBO baseline projections is now available. |

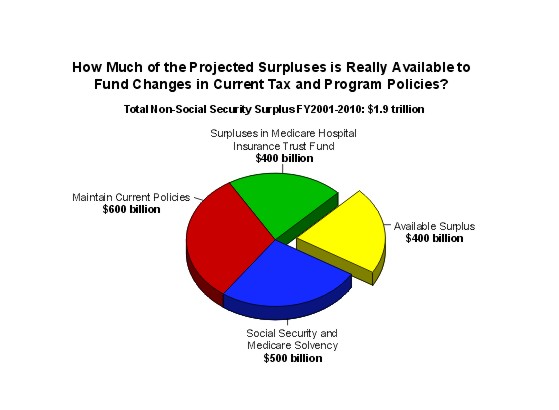

New budget estimates released June 26 by the Office of Management and Budget project that surpluses will total nearly $1.9 trillion over the next 10 years, not counting the surpluses in the Social Security trust funds. These projections are likely to intensify pressures for large tax cuts, and to a lesser extent, increases in expenditures for a variety of programs. Many policymakers and members of the public apparently believe that $1.9 trillion is now available for these purposes.

In fact, the amount available is much smaller than that. When surpluses in the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund are placed off-limits along with Social Security surpluses, as both parties are moving to do, and the cost of maintaining current policies in areas such as aid to farmers, middle-class tax burdens, and discretionary spending are taken into account, the $1.9 trillion figure is cut in half. Furthermore, a significant portion of the remaining funds will be needed to help restore long-term Social Security and Medicare solvency, since policymakers in both parties overwhelmingly reject restoring solvency largely or entirely through benefit reductions or payroll tax increases. As a result, the amount actually available for tax cut and program initiatives (other than Social Security and Medicare solvency measures) may be in the vicinity of $400 billion over 10 years rather than $1.9 trillion.

- One of the few things that the President and Congress have agreed on in recent years is that Social Security surpluses should be used only for Social Security, by which they generally mean that the surpluses should be used to pay down the federal debt and not to finance increases in other programs or tax cuts. The arguments for setting the Social Security surpluses to the side in this manner apply equally to surpluses in the Medicare HI Trust Fund, and the President and Congress seem close to agreement to wall off those surpluses. The House and Senate both have recently approved legislation to this effect. According to Administration estimates, this would reduce surpluses potentially available for changes in tax or spending policies by more than $400 billion, from $1.9 trillion over 10 years to less than $1.5 trillion.

- The projected non-Social Security, non-Medicare HI surpluses that are potentially available to finance tax cuts and program initiatives are further reduced when realistic assumptions are made about renewing an array of expiring tax credits that Congress routinely extends, preventing the encroachment of the Alternative Minimum Tax into the middle class, continuing current "temporary" payments to farmers, and maintaining current discretionary spending levels, adjusted for inflation and changes in the size of the U.S. population. Using realistic assumptions that simply assume the continuation of current policies in these areas (including the real costs of continuing current policies in the baseline does not imply that continuing those policies is necessarily desirable) reduces the estimate of the surpluses available for other uses by close to $600 billion over 10 years. This shrinks the available surpluses from $1.5 trillion to approximately $900 billion.

- In addition, a significant part of the projected surpluses ultimately will be needed as part of Social Security and Medicare reform legislation to restore long-term solvency to these programs; nearly all of the major Social Security proposals offered by lawmakers of either party entail the transfer of large sums from the non-Social Security budget to the retirement system. This is true both of proposals that include individual accounts as a partial replacement for Social Security and of proposals that do not follow such a course.

It is not possible to estimate with any precision how much of the surpluses will be needed as part of solvency packages, since that depends on how far lawmakers are willing to go in reducing Social Security and Medicare benefits or increasing payroll taxes. However, $500 billion or more is likely to be needed for this purpose over the next 10 years. If a Social Security reform package is enacted in the near future that includes benefit cuts and payroll tax increases covering about 70 percent of the amount needed to restore long-term solvency — a level of benefit and tax changes that will be very difficult to achieve politically — then closing the remaining 30 percent of the long-term financing gap will require an infusion of approximately $500 billion over the next 10 years from the non-Social Security, non-Medicare HI part of the budget. If action on Social Security and Medicare reform packages is delayed, a smaller amount of the projected surpluses may be needed over the coming decade, but then still-larger sums are likely to be needed in the future.

How Much of the Projected Surpluses is Available

to Fund Changes in Tax and Program Policies?

(in trillions of dollars)Fiscal Years

2001 - 2010Administration’s June 2000 baseline projection of non-Social Security surpluses

$1.9

Minus:

Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund surpluses

-$0.4

Amounts needed to maintain current policies

-$0.6

Amounts likely to be needed for Social Security and Medicare reforms to achieve long-term solvency

-$0.5

Remaining surpluses available to fund changes in current tax and program policies (including resulting increase in interest costs)

$0.4

If none of the surpluses projected for the next 10 years are set aside for this purpose — and the surpluses are largely used for permanent tax cuts and program increases instead — the amounts needed to help restore Social Security and Medicare solvency are likely to be still greater in the future, but less money will be available to meet these demands. This argues for setting funds aside for this purpose now, even if Social Security and Medicare solvency legislation will not be enacted quickly.

If approximately $500 billion is needed for Social Security and Medicare reform (this amount could be larger or smaller, but almost certainly will total hundreds of billions of dollars), the projected surpluses that remain available for other policy initiatives will equal about $400 billion over 10 years. (This $400 billion would have to cover the cost of the increased interest payments on the debt that would result from using some of the surpluses for tax cuts or increased program expenditures, as well as the cost of the tax cut and program increases themselves.) While $400 billion is a substantial sum, it is far less than the $1.9 trillion some policymakers seem to think is available for tax cuts and program expansions.

Whatever the amount that is available for tax and program initiatives, decisions about the best uses of this money should be made carefully and based on a vigorous debate about the needs and priorities of the nation. The emergence of large non-Social Security surpluses is a very recent phenomenon. Neither lawmakers nor the public have yet gone through a process of weighing the most appropriate uses of the surpluses and establishing priorities. Current Congressional proposals to use the surpluses seem to be more a response to short-term political currents before the fall elections — and to demands from interest groups that have been able to mobilize quickly and get to the front of the line (and in some cases, make large campaign contributions) — than the product of careful, systematic consideration of how to take advantage of the opportunity the economic boom presents to establish priorities for addressing the nation's most critical needs. Before enacting measures such as the pending legislation to repeal the estate tax, at an ultimate cost of $50 billion a year, lawmakers ought to consider the range of potential uses of the projected surpluses and weigh these uses against each other.

|

How Does This Analysis Apply to CBO’s Budget Projections? New budget projections released by the Congressional Budget Office on July 18 show non-Social Security surpluses of $2.2 trillion over the next 10 years. Although these CBO projections are somewhat more optimistic than the Administration’s June baseline projections, which are used as the starting point in this analysis, the points made in this analysis apply as well to the new CBO projections. CBO projects that non-Social Security surpluses will total $2.2 trillion over the next 10 years — $300 billion more than in the Administration’s June baseline projection. But, just as is the case with the Administration’s projections, $1.5 trillion of those surpluses will not be available to fund tax cuts or new program initiatives. Instead, that amount will be needed to pay down the federal debt by the amount of the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund surpluses, to fund the costs of maintaining current policies that are not reflected in the baseline projections, and to reserve funds that will be needed as part of reform packages to ensure long-term Social Security and Medicare solvency. That would leave about $700 billion available to fund tax cuts or new program initiatives under CBO’s projections — $300 billion more than would be left under the Administration’s baseline projections. For a brief description of how this analysis applies in the case of the CBO baseline projections, see https://www.cbpp.org/7-18-00bud.htm |

How Much of the Surplus is Available for Initiatives?

The economic and technical assumptions that underlie the new budget projections could turn out to be too optimistic (or too pessimistic). But if the assumptions prove to be on the mark, the non-Social Security surpluses that will develop if current policies remain unchanged will be considerably smaller than $1.9 trillion over 10 years.

| The OMB and CBO projections of the surplus essentially assume that payments to farmers will be reduced sharply, that all tax credits coming up for renewal will be allowed to expire, and that millions of middle-class families will become subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax and face sizeable tax increases. |

Medicare Trust Fund Surpluses

The President and Congress have agreed that Social Security surpluses should be used only for Social Security, by which they generally mean that these surpluses should be used to pay down the federal debt and not to finance other programs or tax cuts. The arguments for using Social Security surpluses solely for Social Security, rather than for program expansions or tax cuts elsewhere in the budget, apply equally to the Medicare HI trust fund.

Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes are withheld together from paychecks. The payroll taxes collected for both programs are placed in trust funds in which balances are accumulating now, but all of the funds ultimately will be needed to meet future benefit requirements. If the surpluses in the Social Security trust funds are set aside and considered unavailable for tax cuts or program initiatives, the same should logically be true of the Medicare HI trust fund. Some $400 billion of the roughly $1.9 trillion in projected non-Social Security surpluses over the next 10 years consists of projected surpluses in this trust fund.

Both parties now are moving to make surpluses in the Medicare HI trust fund off-limits for tax cuts or increases in other programs. The Administration has proposed such an approach. And, as noted above, the House of Representatives on June 20 passed a measure intended to have this effect by a 420-2 vote.

It is important to note that while dedicating all of the Social Security and Medicare HI trust fund surpluses to debt reduction may be a wise policy today and represents a generally desirable goal, it is not a sound idea in all circumstances. It makes sense now, when the economy is booming. But if the economy were to slow markedly or plunge into recession and anticipated surpluses evaporated, it would be foolish to enact tax increases or spending cuts just to ensure that the rest of the budget is balanced and all of the Social Security and Medicare surpluses go to reduce debt. Instead, a fiscal policy that helped to stimulate the economy would be appropriate in such circumstances.

Taxes and Mandatory Spending

When the Administration and the Congressional Budget Office construct the budget "baselines" on which their surplus projections rest, they follow a series of basic rules. Under these rules, OMB and CBO generally assume no legislation will be enacted that makes any changes in current laws related to taxes or entitlement programs, even if legislation is needed simply to extend a current policy. Because of this rule, these two agencies exclude from their surplus projections the costs of legislation that is needed in several politically sensitive areas to maintain current policies and is virtually certain to be enacted. This includes legislation to maintain payments to farmers in future years, legislation to extend an array of popular tax credits that are scheduled to expire every few years and that Congresses and Administrations of both parties routinely renew, and legislation to prevent the Alternative Minimum Tax from hitting millions of middle-class families that do not use tax shelters and raising their taxes in the years ahead. (The Alternative Minimum Tax was created to prevent wealthy investors from using so many tax shelters that they owe little or no income tax; in the years ahead, however, it will have a much more widespread impact unless changes in it are enacted.) Whatever the respective merits of these pieces of legislation (and there is question about the wisdom of some of them), they would merely continue current policy. Virtually every knowledgeable observer agrees that legislation to continue these policies is almost certain to be enacted.

The budget surplus projections do not include the cost of any of these steps. The surplus projections essentially assume that payments to farm operators will be slashed compared to current levels, that all of the tax credits coming up for renewal will be allowed to die, and that millions of middle-class families will become subject to the AMT for the first time and face sizeable tax increases. Maintaining current policies in these areas is likely to consume more than $200 billion of the projected surpluses over the next 10 years.

Discretionary Spending

Administration and CBO projections generally assume that discretionary spending (spending for non-entitlement programs that is controlled by annual appropriation bills) will grow only at the rate of inflation, without any increase to reflect growth in the U.S. population. The projections thus assume that overall expenditures for discretionary programs will decline in purchasing power on a per person basis (or, to use more technical terms, the projections assume that these expenditures will decline on a real per capita basis). This means, for instance, that the amount of education spending per pupil will decline in inflation-adjusted terms.

| Since proposals to extend Social Security and Medicare solvency by relying largely or entirely on benefit reductions or payroll tax increases do not appear politically feasible, substantial transfers from the general fund to Social Security and Medicare are likely to be an essential component of any solvency package. |

As former CBO directors Rudolph Penner and Robert Reischauer have observed, this is not realistic. There is a consensus among a majority in Congress and the Administration that defense spending (almost all of which is discretionary spending) should grow. In addition, non-defense discretionary spending grew 20 percent after adjusting for inflation between 1990 and 2000 and 10 percent after adjusting for population growth as well as inflation. If non-defense discretionary spending grew at these rates during a period marked primarily by pressures to shrink budget deficits, such spending is unlikely to be treated parsimoniously in a period of surpluses. The notion that real per capita discretionary spending (spending adjusted for inflation and population growth) will fall amidst budget surpluses is not credible. (It may be noted that when measuring spending growth in Texas, Governor George W. Bush and his campaign regularly measure changes in spending on a real per capita basis. They have argued, reasonably, that this is the appropriate standard to use.)

Assuming that overall discretionary spending will remain unchanged in purchasing power on a per person basis reduces the projected surpluses available for tax and program initiatives by an additional $350 billion over the next 10 years. While this is a much more realistic assumption than assuming that discretionary spending will keep pace only with inflation and will decline in real terms on a per person basis, it probably understates the likely path of discretionary spending. As Robert Reischauer has noted, "it will be a Herculean feat" to keep discretionary spending from growing in real per capita terms in a time of surpluses.

Using realistic assumptions about renewing the expiring tax credits, continuing payments to farmers, fixing the AMT, and maintaining discretionary spending on a real per capita basis — and setting aside the surpluses in the Medicare HI trust fund — results in a total reduction of the amount of projected surpluses available for tax and program initiatives from nearly $1.9 trillion over 10 years to approximately $900 billion.

Funding Needed for Long-term Social Security and Medicare Reform

Despite the improved budget outlook, Social Security and Medicare face rising costs and funding shortfalls when the number of baby-boomers who draw benefits grows in the decades ahead. Both parties have pledged to enact reforms that will ensure that Social Security and Medicare remain solvent and able to pay promised benefits for decades to come.

Proposals to extend the solvency of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds by relying solely on benefit reductions or payroll tax increases do not appear politically feasible; they are shunned by both parties. As a consequence, making substantial transfers from the general fund to these trust funds appears to be an essential component of any politically feasible reform package to restore long-term solvency to these programs. For example, even the Medicare reform legislation that Senator John Breaux and Representative Bill Thomas have proposed, which contains controversial changes in the Medicare benefit structure that many lawmakers think go too far, would close less than half of the long-term Medicare financing gap. It would leave a need for large general revenue infusions unless payroll taxes are raised significantly.

It is impossible to know precisely how much funding will be needed from the general budget to help restore long-term Social Security and Medicare solvency. But it is hard to imagine these funding requirements will not amount to some hundreds of billions of dollars over the next 10 years. According to the Social Security Trustees, solvency of the Social Security trust funds for 75 years would be achieved if permanent increases in trust fund income or reductions in Social Security expenditures equal to 1.89 percent of taxable payroll were enacted. The 1.89 percent of taxable payroll amounts to more than $1 trillion over the next 10 years. The amount needed to restore the solvency of the Medicare HI Trust Fund, using the Medicare trustees' forecast, would amount to about $700 billion over the next 10 years.

Even if the general fund contribution to Social Security and Medicare solvency were to constitute only about 30 percent of a reform package enacted now, the contribution needed would be approximately $500 billion over the next 10 years. Of course, Social Security and Medicare reform is not likely to occur in the immediate future, and general fund contributions may not begin for a number of years. Delaying reform, however, will have the effect of increasing the annual amounts needed in the future. Moreover, taking portions of current general fund surpluses that eventually will be needed for these solvency efforts — and using those funds instead to fund permanent tax cuts or program increases — would mean that fewer resources would be available in the future to cover the larger amounts that would be needed as part of a solvency package. Failing to set aside a portion of the projected surpluses for general-revenue transfers would likely make it more difficult to pass legislation at a later date that ensures long-term solvency.

| Neither lawmakers nor the public have yet gone through a process of weighing various possible uses of the surplus and establishing priorities. |

If $900 billion is available over 10 years for tax cuts and program initiatives and $500 billion of this amount is set aside for Social Security and Medicare solvency legislation (the exact amount to set aside for solvency legislation is somewhat arbitrary), that would leave $400 billion over 10 years for other purposes. Even if the amount needed for Social Security and Medicare solvency efforts proves to be only $300 billion (although assuming that no more than this amount will be needed probably is not wise), the available surpluses will be about $600 billion. While these are substantial amounts, they are considerably less than the $1.9 trillion some policymakers may be tempted to dispose of. (Note: To avoid creating a deficit, the costs of tax cuts and program increases must be less than the amount of the available surpluses. Tax cuts and spending increases will cause the federal debt to be higher than OMB's baseline projections assume, which will cause interest payments on the debt to be greater than the baseline projections show and to consume a portion of the available surpluses.)

Assessing National Priorities

| It is unlikely there would be a national consensus that policies such as repealing the estate tax at an ultimate cost of $50 billion a year should receive higher priority than reducing the ranks of the uninsured, ameliorating child poverty, strengthening the Medicare benefit package, addressing environmental threats, or reducing taxes more broadly and equitably. |

Whatever the exact amount that remains available for changes in taxes and programs, Congress and the President should carefully assess national priorities in allocating resources among competing claims. The surpluses anticipated in the next 10 years present a unique opportunity to deal with critical national needs. This opportunity should not be squandered either by allocating more resources than is prudent or by dividing up the resources based on which interest groups manage to gin up effective (if often misleading) public relations campaigns most quickly or on what public opinion polls indicate about the near-term appeal of certain proposals, especially when the longer-term costs and consequences of such proposals are largely hidden from view.

Congress and the President should carefully weigh, and foster debate on, the relative long-term benefits of various uses of the available surpluses. There should be a national debate on what the nation's most critical priorities are. In our view, the leading contenders include the following (not all of which could be funded adequately from the surpluses that realistically are available):

- Greatly reducing the number of people without health insurance, which now stands at 44 million — or more than 16 percent of the U.S. population — a level unheard of among other western industrialized nations.

- Assisting those who have not enjoyed the fruits of the economic boom of the 1990s — particularly working-poor families and poor elderly and disabled individuals — and mounting significant efforts to reduce child poverty, which remains far higher here than in Canada or western Europe. In addition, modest increases in U.S. economic aid targeted on poor nations could result in substantial benefits for the 1.2 billion people who, according to the World Bank, survive on less than $1 a day, and whose living conditions often include severe health risks.

- Bringing the Medicare benefit package into the 21st century, including providing prescription drug coverage, protection against catastrophic costs, and some long-term care insurance. (These benefit expansions may be partially paid for by premiums.)

- Providing increased funds (in the case of discretionary spending, above current levels adjusted for inflation and population) for activities that represent investments in the future, such as selected education, job training, environmental clean-up and protection, and infrastructure improvements. (It may be possible to offset a portion of these costs through reductions in funding for programs that no longer provide significant benefits, but additional resources still would be needed.)

Tax cuts also have a place on this list. The scope of tax reductions needs to be restrained, however, to avert revenue losses that are overly costly either now or in years outside the 10-year budget window. In addition, tax cuts that primarily benefit high-income individuals, the group that has gained the most income and wealth during the economic boom, should not qualify as pressing national priorities. Preference should be accorded to tax reductions that assist lower- and moderate-income working families, as well as tax changes that make the tax system simpler, fairer, and more supportive of economic growth by lowering rates for most workers and broadening the tax base, rather than by piling more special tax breaks into the tax code.

When critical national needs are carefully weighed, it is difficult to believe there would be a national consensus that policies such as repealing the estate tax — which would ultimately cost $50 billion a year and provide extremely large tax reductions to the nation's wealthiest individuals while doing little or nothing to promote economic growth — should be accorded higher priority than reducing the ranks of the uninsured, ameliorating child poverty, strengthening the Medicare benefit package, addressing environmental dangers, or reducing taxes in ways that distribute the tax cut benefits more broadly and equitably and have the potential to increase growth.