|

April 21, 2006

A Taxpayer Bill of Rights by Any Other Name:

Montana's "Stop OverSpending" Proposal is a TABOR

by

Karen Lyons and Iris J. Lav

Summary

A proposed ballot initiative in Montana to limit

state spending — “Stop OverSpending” or SOS — is similar in its basic structure

and effect to Colorado’s TABOR. Montana’s SOS proposal includes all three

factors that make Colorado’s TABOR (Taxpayer Bill of Rights) the most severe

state budget limit in the country:

- it is a constitutional amendment,

- it restricts growth to a

population-change-plus-inflation formula, and

- it requires voter approval to spend above

the limit.[1]

SOS can therefore be expected to cause a

deterioration in public services in Montana similar to that produced by TABOR in

Colorado.

During the twelve years since TABOR was adopted

in Colorado, K-12 funding declined to 49th in the nation, and higher education

funding dropped by 31 percent. In addition, the share of low-income children

lacking health insurance doubled at a time that it was dropping nationally, and

Colorado fell to near last in the nation in providing on-time full vaccinations

to the state’s children.

These problems led Coloradoans to approve in

November 2005 a statewide measure to suspend TABOR’s

population-growth-plus-inflation formula for five years in order to allow the

state to restore a portion of its fundamental public services. To date,

Colorado is the only state to have adopted a TABOR, as well as the only state to

have voted to suspend it.

Proponents of SOS claim that their proposal has

been designed to avoid the problems TABOR brought to Colorado. However, the

differences between the two proposals are minor and at best, will only slightly

mitigate the deleterious effects of such a strict limit. SOS would negatively

affect the public services upon which Montanans depend, such as health care,

education, and public safety, just as TABOR did in Colorado.

What Makes TABOR So Unique

TABOR is a very specific type of tax and

expenditure limit; in fact, Colorado is the only state in the nation with a

TABOR. While 28 other states have tax and expenditure limits, none of their

limits have the combination of the three core elements that set TABOR apart and

render it the most rigid limit in the country.

- Colorado’s TABOR is in the state constitution.

If a limit in the constitution is found to be flawed or harmful to the state,

it can be changed only by waging a costly statewide campaign on the ballot.

- Colorado’s TABOR limits the growth of public

services to a population- growth- plus- inflation formula. This formula

virtually guarantees that state services will have to be cut every year

because inflation and general population growth do not adequately measure the

increase in the cost of what the state buys, including health care, education,

and services to the growing elderly population and populations with special

needs.

- Colorado’s TABOR requires a vote of the people

to override its limit temporarily in response to unusual circumstance.

This cumbersome process greatly limits the flexibility of the governor and

legislature to adapt to changing fiscal circumstances and priorities of the

citizens of the state. It too can prove very costly. For example, over $10

million was spent by the proponents and opponents of the successful effort to

temporarily override TABOR in Colorado.

Any proposed spending limit that includes these

three elements is a TABOR because it will impair the ability of a state to

provide an adequate level of services to its residents. Other

characteristics, such as how excess revenue is handled, what happens to the

limit during a downturn and the portion of the budget covered by the limit are

of lesser importance than the three key dimensions described above.

The Consequences of TABOR

A growing body of evidence shows that TABOR

contributed to a deterioration in the availability and quality of nearly all

major public services in Colorado. Colorado voters recently chose to suspend

TABOR for five years, in part to restore some of the service cuts it induced.

The Colorado experience has serious implications for the residents of Montana

because SOS would likely lead to similar outcomes in Montana.[2]

- Since its

enactment in 1992, TABOR has contributed to declines in Colorado K-12 education

funding. Under TABOR, Colorado declined from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12

spending as a percentage of personal income. Colorado’s average per-pupil

funding fell by more than $400 relative to the national average.

- TABOR has played a major role in the

significant cuts made in higher education funding. Under TABOR,

higher education funding per resident student dropped by 31 percent after

adjusting for inflation. As a result, tuitions have risen. In the

last four years, system-wide resident tuition increased by 21 percent after

adjustment for inflation.

- TABOR has led to drops in funding for public

health programs. Under TABOR, Colorado declined from 23rd to 48th in the

nation in the percentage of pregnant women receiving adequate access to

prenatal care. Colorado also plummeted from 24th to 50th in the nation in the

share of children receiving their full vaccinations. Only by investing

additional funds in immunization programs was Colorado able to improve its

ranking to 43rd in 2004.

- TABOR has hindered Colorado’s ability to

address the lack of medical insurance coverage for many children and adults in

the state. Under TABOR, the share of low-income children lacking health

insurance doubled in Colorado, even as it fell in the nation as a whole.

Colorado now ranks last among the 50 states on this measure. TABOR has

also affected healthcare for adults: Colorado dropped from 20th to 48th for

the percentage of low-income non-elderly adults covered under health

insurance.

SOS and TABOR Share the Same Heart: the Flawed

Population-Growth-Plus-Inflation Formula

TABOR’s central flaw is its

population-growth-plus-inflation formula. This formula is not a “soft cap,” nor

does it allow state services to grow at a “reasonable rate” as SOS proponents

claim.[3]

A population-growth-plus-inflation formula would not allow the state to

maintain year after year the same level of programs and services it now

provides. Instead it would shrink public services over time and hinder the

state’s ability to provide its citizens with the quality of life and services

they need and demand.[4]

Population

The first part of the

population-growth-plus-inflation formula is the change in overall population

growth. Overall population growth, however, is not a good proxy for the change

in the populations served by public services. The segments of the population

that states serve tend to grow more rapidly than the overall population used in

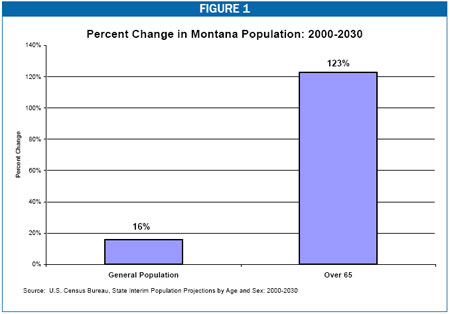

the formula. An example is senior citizens. According to the U.S. Census

Bureau, Montana’s total population is projected to increase by 16 percent from

2000 to 2030, while Montana’s population aged 65 and older is projected to more

than double from 2000 to 2030.[5]

As Montana’s elderly population begins to increase, so will the cost of

providing them the current level of health care and other types of services. The

allowable state spending limit, however, would prevent health care and other

services from growing with need because it would be calculated using the much

slower growing total population. Services to the elderly could be maintained

only if Montana residents were willing to make sharp cuts in other areas of the

state budget, such as education or public safety.

Inflation

The second part of the formula — inflation — also

does not accurately measure the change in the cost of providing public

services. The measure of inflation in the Montana TABOR initiative is the

nationwide “Consumer Price Index-All Urban Consumers (CPI-U),” which is

calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPI-U measures the

change in the total cost of a “market basket” of goods and services purchased by

a typical urban consumer. Since a typical urban consumer spends a majority of

his or her income on housing, transportation, and food and beverages, those

items are the primary drivers of the CPI-U. By contrast, the state of Montana

spends its revenue primarily on education, health care, and corrections. In

short, the market baskets of spending are entirely different.

Moreover, the “goods”— or public services— in the

state of Montana’s basket (and in every other state’s) are in economic sectors

that are less likely to reap the efficiency and productivity gains achieved by

other sectors of the economy. For example, teachers can only teach so many

students, and nurses can only care for so many patients. As a result, the costs

of these public services are rising faster than the costs in other sectors.

Indeed, the items in the “basket of goods” most heavily purchased by states —

such as health care, education, and prescription drugs — have seen significantly

greater cost increases in the past decade than the items in the basket of goods

purchased by consumers, and those faster-growing costs are expected to continue.

Limiting the growth in public expenditures to a formula that uses the rate of

growth in general inflation will not affect the level or growth of these costs

in the economy; instead, it will affect the quantity and/or quality of public

services the state is able to provide to its citizens.

On the Cutting Block

It is also important to note that all programs in

the Montana General Fund — not just those with cost pressures exceeding the

population-growth-plus-inflation level — are threatened by a rigid

population-growth-plus-inflation limit. This is because SOS applies to Montana’s

entire General Fund budget. And while the General Fund only makes up 37 percent

of total state expenditures, it provides the majority of funding for K-12

education, higher education, health care and corrections. Under SOS, if one

spending area were to grow faster than population growth plus inflation (for

instance due to cost pressure, court order, or popular demand), then another

spending area would have to grow at a slower pace — which would mean a reduced

level of services in this second area.[6]

This type of formula-driven budgeting hamstrings meaningful discussions about

the priorities of the citizens and the ability of the state to respond to them.

Despite Minor Differences, SOS is Still a TABOR

Proponents of the Montana initiative seek to

distance themselves from the problems TABOR has caused in Colorado. They have

changed the name of their TABOR to SOS and have made some slight improvements

over Colorado’s TABOR. However, these improvements, which include freezing the

limit during a downturn and a reserve fund to be used as a safeguard against

revenue shortfalls, do not fully fix Colorado’s most talked about problem: the

“ratchet.”

During a recession, states typically reduce the

quantity of public services they provide. A ratchet prevents public services

from ever recovering from these reductions because the recession-depressed

service level becomes the base to which the population-growth-plus-inflation

formula is applied. For example, revenues in Colorado fell during the

recession, and that reduced level became the base for calculating allowable

revenue growth in all subsequent years. As revenue growth returned to normal,

spending could not because the TABOR limit was stuck at the low recession level.

This prevented Colorado from restoring cuts made in public services during the

downturn.

If Colorado had not suspended TABOR for five

years in November 2005, it would have had to continue making deep reductions in

public services each year for a number of years to come. To avoid facing this

problem again, Coloradoans also voted to change the way the formula is applied.

At the end of TABOR’s five-year suspension, the population-growth-plus inflation

formula will be calculated from the TABOR limit in the previous year, rather

than from actual revenues.

Limit Freeze During Downturn

In the SOS proposal, the dollar amount of the

limit would be frozen during an economic downturn. While the limit would not

ratchet backward during a downturn, as it did in Colorado, it would remain

fixed; it could not continue to rise by the change in population and inflation.[7]

Thus, the SOS

proposal would only mitigate and not eliminate the ratchet. If the limit

were frozen in response to a downturn, public services would fall substantially

behind even the standard of need recognized in the TABOR formula; the population

would continue to grow and inflation would continue to push up the cost of

services over those years, but the limit would not be adjusted to reflect this

growth. So while expenditures wouldn’t be ratcheted back to recession levels,

they would stagnate. And as revenue growth fully recovered, expenditures could

not because they would be based on this frozen level.

Reserve Fund

The SOS proposal briefly mentions a reserve fund

that is “to be used as a safeguard against shortfalls in state revenue below the

spending limit.” However, it does not offer any information on how large this

reserve fund would be, how much of the revenues above the limit would be

deposited into the fund, whether those deposits would be mandatory, and whether

transfers from the reserve fund would be automatic or would require a vote of

the Legislature. Furthermore, the language concerning whether transfers from the

reserve fund to the general fund would be counted as expenditures in setting the

next biennium’s limit is unclear.

Without knowing these specifics of the

reserve fund, it is impossible to know what role it could play in moderating the

ratchet. In the best of all circumstances, a well designed reserve fund (or

budget stabilization fund) could eliminate a ratchet. But for a reserve fund to

eliminate a ratchet it must be sufficiently large to compensate for all revenue

shortfalls during the downturn, it must not face obstacles to its use when it is

needed, and transfers from the reserve fund to the general fund must count as

expenditures for calculating the subsequent year’s limit. Given the lack of

information surrounding the reserve fund in Montana’s SOS proposal, it is

doubtful that it would solve the ratchet problem[8]

Regardless, it

was not the ratchet that caused the sharp decline in public services in

Colorado, but rather the operation of the population-growth-plus-inflation

formula for more than a decade. Public services in Colorado declined

significantly before the 2001 recession began, and thus before the ratchet could

have had any effect. For example, between 1992 (when TABOR took effect) and

2001, Colorado fell from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12 education spending

as a percentage of personal income and from 23rd to 45th in access to prenatal

care, a sign of funding shortages in local health clinics.

Conclusion

Despite assertions that SOS is an improved

version of Colorado’s TABOR, Montana’s SOS proposal contains the three core

elements of Colorado’s TABOR. It is these three aspects that make TABOR so

unique and so damaging to a state’s public services. Thus, SOS can be expected

to cause declines in public services in Montana similar to those experienced in

Colorado under TABOR.

| |

Constitutional Amendment |

Limits Growth

to Population + Inflation Formula |

Voter Approval

to Override Limits |

| Colorado's TABOR |

|

|

|

| Montana's SOS |

|

|

|

End Notes:

[1] Voter approval is not required in

cases of declared emergencies, such as natural disasters or enemy attack.

[2] For a more detailed analysis of

the problems experienced in Colorado under TABOR, please see David Bradley

and Karen Lyons, “A Formula for Decline: Lessons from Colorado for States

Considering TABOR,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2005.

Available at:

https://www.cbpp.org/10-19-05sfp.htm.

[3] Sources: “Should

Montana limit government spending?,” Editorial by Sen. Balyeat, The

Billings Outpost, March 23, 2006; Rep. Mendenhall quoted in “Analyst rips

spending cap proposal,” Helena Independent Record, March 7,

2006.

[4] For a more detailed analysis of

the problems with the population-growth-plus-inflation formula, please see

David Bradley, Nick Johnson and Iris Lav, “The Flawed “Population Plus

Inflation” Formula: Why TABOR’s Growth Formula Doesn’t Work,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, January 2005. Available at

https://www.cbpp.org/1-13-05sfp3.htm

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, State Interim

Population Projections by Age and Sex: 2000-2030, Table 4. Available at

http://www.census.gov/population/projections/PressTab4.xls

[6] Sen. Balyeat has acknowledged

that “SOS” would require such cuts: "There's nothing in this initiative as

such that would specifically limit school spending. ... If they prioritize

school spending, other things would have to have slower growth." Quoted in

“Groups raise red flags over proposed cap on spending,” Great Falls Tribune,

March 7, 2006.

[7] Technically, the TABOR limit for

a biennium would be set as the greater of previous biennium’s appropriations

adjusted for inflation plus population growth or the largest limit for any

previous biennium. Using the largest limit for any previous biennium

basically freezes the TABOR spending limit during an economic downturn and

keeps it frozen until revenues recover.

[8] For a more detailed analysis of

the role of a budget stabilization fund can play in moderating the ratchet,

please see David Bradley, Iris Lav and Karen Lyons, “A Faulty Fix:

Repairing the “Ratchet” Will Not Repair TABOR,” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, March 2005. Available at: https://www.cbpp.org/3-21-06sfp.htm.

|