Future Tax Cuts and the Economy in

the Short Run

by Peter

Orszag(1) and Robert

Greenstein

| PDF of this report |

| Related Testimony: The Budget and the Economy, Peter Orszag, U.S. Senate Committee on the Budget, 1/29/02 If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The tax cut enacted last year has important effects on the economy in both the short run and the long run. Despite some confusing rhetoric that has marked the debate over the tax cut in recent weeks, its short-run and long-run effects are distinct. This paper focuses on the short-run effects.

The tax cut has two countervailing short-run effects on the economy:

- The tax cuts that have already taken effect exert a positive effect on the economy in the short run. As one example, the rebates sent out in August and September provided timely stimulus to the economy; they helped boost consumer spending in a weak economy. (The early evidence, however, suggests the beneficial impact was likely to have been relatively modest. The evidence suggests that most households saved, rather than spent, the rebates.(2))

- The tax cuts that are scheduled for future years and are

not yet in effect exert a negative effect on the economy in the short run. About half

of the long-term cost of the tax legislation takes effect after 2002, with nearly all of

the provisions not now in effect scheduled to take effect in 2004 or years after that, a

time well after the current recession is expected to have ended. These scheduled future

tax cuts adversely affect the economy today because they immediately raise

long-term interest rates and thereby increase the cost of business investment and home

mortgages.

The increase in long-term interest rates occurs because financial markets recognize that, due to the tax cut, interest rates in the future will increase. There are two ways to see how the tax cut affects future interest rates. First, one effect of the tax cut is that the government will be saving less than it otherwise would (i.e., it will be running much smaller surpluses). As a consequence, the pool of saving available for investment will be reduced. Firms thus will compete for a smaller pool of investment funds. Due to the laws of supply and demand, this competition for a smaller pool of investment pushes up the price of borrowing these funds — that is, it raises future interest rates.

An alternative (but fundamentally equivalent) way of grasping the relationship between the tax cut and interest rates starts with the fact that the amount of debt the government is projected to pay down in the future will be smaller (and the national debt will consequently be larger) as a result of the tax cut. The amount of Treasury bonds held by the public will therefore have to be higher in the future than it would be without the tax cut. To persuade investors to hold more bonds, the government will have to offer a higher interest rate.

For these reasons, the large tax cut will exert upward pressure on future interest rates. Since financial markets determine long-term interest rates today largely on the basis of what they expect shorter-term interest rates to be in the future, the expected increase in shorter-term interest rates in the future drives up long-term interest rates now. In other words, the increase in interest rates that is expected to occur in five years or so raises interest rates on 10-year bonds today. That, in turn, impedes economic activity today.

Bush economic adviser Lawrence Lindsey argues in a recent op-ed article that expected future tax reductions can encourage economic activity today and therefore have a positive rather than a negative effect on the economy in the short run.(3) This argument, however, is inconsistent with economic research on this issue, which strongly suggests that people tend not to spend tax cuts prospectively; instead, they largely wait until the money is in their pockets. For example, one recent paper examined the Reagan tax cuts; those tax cuts took effect in phases, with one set of tax reductions occurring in October 1981, another set occurring in July 1982, and a third set of tax cuts taking effect in July 1983. The paper found that households generally did not increase their spending until the tax cuts actually were in effect.(4) Another paper, by well-known economist James Poterba of MIT, studied the 1975 tax rebate, which was announced before it was paid. This research, too, concluded that "consumers do not adjust consumption in anticipation of tax changes."(5) Still other research by David Wilcox of the Federal Reserve Board suggests that households do not respond to announced changes in Social Security benefits until the cash is actually in their hands.(6) The evidence strongly suggests that households do not respond much to tax cuts or other policy changes until the cash is in their hands.

These findings suggest that any short-run benefit from tax cuts that will not take effect until future years is quite limited, despite Mr. Lindsey's assertions to the contrary. Mr Lindsey also fails to take into account the impact of future tax cuts on long-term interest rates.(7)

In short, the overall net effect on the economy today from tax cuts scheduled for the future is likely to be negative. The adverse impact from higher long-term interest rates is considerably larger than any small, positive impact that may result from increased spending now in response to future tax cuts.

This analysis examines in more detail the connection between future tax cuts and long-term interest rates, which is the mechanism through which future tax cuts impede current economic activity.

What Has Happened to Interest Rates?

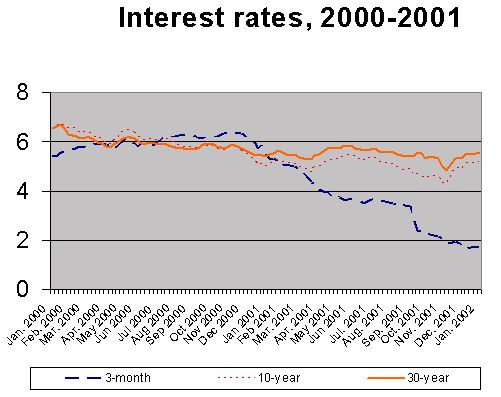

It is instructive to review what has happened to interest rates recently. Over the past year, as the Federal Reserve has moved aggressively to bolster a weakening economy, short-term interest rates have declined sharply. Between the beginning of 2001 and the beginning of 2002, the interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills fell from 5.5 percent to 1.7 percent.(8)

Experts Comment on

the Relationship Between the Budget, Several prominent commentators have noted the relationship between the budget and long-term interest rates: Alan Greenspan (July 2001):

Alan Greenspan (January 2002):

Robert Rubin (January 2002):

Abby Joseph Cohen (January 2002):

_________________________________ |

Normally, when short-term rates decline, long-term interest rates do so as well. Over the past year, however, long-term rates have remained fairly flat despite the steep decline in short-term rates. The interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds actually increased slightly during 2001, from 5.0 percent to 5.2 percent (see figure). In other words, short-term interest rates have declined substantially but long-term rates have not.

Although the precise relationship may depend on many factors and fluctuates over time, long-term rates have tended to move by about half as much as short-term rates, on average, over the past two decades. Based on this historical relationship, the 3.8 percentage point decline in short-term rates should have corresponded to a decline in long-term rates of a bit under 2 percentage points. Instead, long-term rates increased slightly. In other words, according to the average historical relationship between long-term rates and short-term rates over the past two decades, a decline of almost 2 percentage points on long-term interest rates was "missing" during 2001.

An alternative perspective is obtained by examining what happened to interest rates during the 1990-1991 recession relative to what has happened thus far during the current recession. The current recession began in March 2001; in the nine months since March, short-term interest rates have fallen by 280 basis points (2.8 percentage points) while long-term rates have risen slightly. In the nine months following the beginning of the 1990-1991 recession, by contrast, short-term interest rates fell by 200 basis points (2 percentage points) and long-term rates fell by more than 40 basis points (0.4 percentage points). Based on the relationship between short-term rates and long-term rates from the 1990-1991 recession, we would thus have expected long-term rates to fall by about 60 basis points since March 2001. Instead, they rose by about 20 basis points — so roughly 80 basis points are "missing."

The upshot is that given the declines in short-term rates, a decline in long-term rates of somewhere between 80 basis points (based on the relationship between short rate and long rates from the 1990-1991 recession) and 200 basis points (based on the historical average relationship) is "missing." Long-term rates remain relatively low, which has helped to shore up the housing market, but they would have been expected to be lower given the decline in short-term rates.

This failure of long-term rates to decline with short-term interest rates has had an adverse effect on the economy. The substantial decline in long-term rates that would have been expected, given the decline in short-term rates, would boost investment spending and reduce mortgage payments, thereby spurring the economy. A critical question is why long-term rates have failed to decline.

The Tax Cut and Long-Term Interest Rates

Many factors influence interest rates. It is difficult, if not impossible, to parse out precisely the specific impact of the various factors that affect interest rates. Nevertheless, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, Goldman Sachs economist Abby Joseph Cohen, and others have concluded that the tax cut enacted last year appears to have played an important role in keeping long-term rates higher than they would otherwise be. For example, in a speech delivered on January 11, 2002, Chairman Greenspan noted that "over the past year, some of the firmness of long-term interest rates probably is the consequence of the fall of projected budget surpluses and the implied less-rapid paydowns of Treasury debt."(14)

In earlier Congressional testimony, Greenspan indicated there was "no question" that the tax cut enacted last year affected long-term interest rates.(15)

Cost of Tax Cuts Not Yet in Effect Exceeds Entire Social Security Shortfall To gain some perspective on the magnitude of the tax cuts not yet in effect, one can compare their cost to the magnitude of the Social Security shortfall. The Social Security Trustees and actuaries project that the Social Security shortfall over 75 years (the period over which Social Security's financing situation is routinely measured) equals 0.7 percent of GDP over that period.a Based on the Joint Tax Committee's estimates of the cost of the tax cuts not yet in effect, their cost over 75 years (assuming the tax cuts are extended) equals 0.8 percent of GDP. In other words, freezing the tax cuts and transferring the preserved revenue to the Social Security system would fully restore Social Security solvency for the next 75 years.b (We do not mean to suggest this is the best way to address Social Security's long-term financing problems. Nevertheless, this comparison helps to place in perspective the size of the tax cuts not yet in effect.) a Under the Social Security actuaries' intermediate projections, the projected 75-year deficit amounts to 1.86 percent of taxable payroll. Over this 75-year-period, taxable payroll will amount to 37.6 percent of the Gross Domestic Product when both are expressed in present value. As a result, the 75-year imbalance amounts to 0.7 percent of GDP, which is equal to 1.86 percent of taxable payroll multiplied by 37.6 percent. The figure of 0.7 percent of GDP appears in Table VI.E5 on page 150 of the Trustees Report of March 19, 2001.b For more on comparison the tax cut and the long-term deficit in Social Security, see Richard Kogan, Robert Greenstein, and Peter Orszag, "Social Security and the Tax Cut," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised December 13, 2001. |

The reason that one would expect the tax cut to affect long-term interest rates is that the tax cut substantially reduces the amount of debt the government will pay down over the next 10 years. That drives up future interest rates, and since financial markets determine long-term interest rates today largely on the basis of what they expect shorter-term interest rates in the future to be, the expected increase in shorter-term interest rates in the future drives up long-term interest rates immediately. The long-term budget deterioration associated with the tax cut therefore tends to keep long-term interest rates higher than they would otherwise be.

The Bush Administration has sought to deny that the tax cut has played any role in keeping long-term rates high. When asked recently to respond to Greenspan's comments on long-term rates, Lawrence Lindsey responded: "I disagree with the implication here that it was the tax cuts."(16)

Despite the Administration's protestations to the contrary, however, every major macroeconomic model — such as the models the Federal Reserve uses — indicates that the tax cut would raise long-term rates relative to what they would be in the absence of the tax cut.(17)

For example, extrapolating published results from the macroeconomic model used by the Federal Reserve Board would suggest that the tax cut would raise 10-year interest rates by between 56 basis points and 80 basis points after one year (i.e., by between 0.5 and 0.8 percentage points), and by between 77 and 112 basis points after 10 years.(18) (These figures reflect an extrapolation of previously published estimates from the Federal Reserve, adjusted to fit the cost of the tax cut; they do not reflect an official estimate from the Federal Reserve of the effects of the tax cut.)

Similarly, in 1995, the Congressional Budget Office evaluated the impact of an improvement in the five-year budget balance of about 2.2 percent of GDP. CBO concluded that this improvement in the budget balance would lower 10-year interest rates by 170 basis points after five years, with more moderate interest rate reductions in the first four years.(19)

Based on this analysis, the expectation would be that last year's tax cut would cause 10-year rates to be about 90 basis points higher after five years than they otherwise would be.

To support their argument that the tax cuts do not affect long-term interest rates, Administration officials and their surrogates contend that the econometric literature does not demonstrate a robust relationship between budget shifts and interest rates. To be sure, the results from the literature are mixed; one review of the literature noted that "it is easy to cite a large number of studies that support any conceivable position."(20)

But it is assuredly not the case, as some Administration officials have implied, that the literature conclusively demonstrates that fiscal policy does not affect interest rates. The wide array of results found in the literature simply suggests that efforts to quantify any relationship between fiscal policy and interest rates have been flawed. As two leading economists, Douglas Elmendorf of the Federal Reserve and Gregory Mankiw of Harvard, conclude in a summary of the literature: "Our view is that this literature...is not very informative."(21)

While the econometric literature is not helpful here, the considered opinion of most leading institutions and observers in the field is that a relationship between fiscal policy and long-term interest rates does exist. Every major macroeconomic model reflects such a relationship. So does the professional judgment of experienced market observers such as Alan Greenspan and Robert Rubin.

The Reagan and First

Bush Administrations, Martin Feldstein, and John Taylor The Economic Report of the President issued by President Reagan's Council of Economic Advisers in 1984 stated: "Measures to reduce the budget deficit would lower real interest rates and thus allow the investment sector to share more fully in the recovery that is now taking place primarily in the government and consumer sectors."a(22) The same logic would suggest that reducing future surpluses would raise real interest rates and discourage investment. The Economic Report of the President issued by the former President Bush's Council of Economic Advisers in 1991 stated, in discussing the 1990 budget agreement: "The new budget law, for example, reduces the budget deficit from what otherwise would be expected. Economic theory and empirical evidence indicate that expectations of deficit reduction in future years, if the deficit reduction commitment is credible, can lower interest rates as financial market participants observe that the government will be lowering its future demand in the credit market. That can mitigate a potential short-run contractionary effect. In other words, expectations of lower interest rates in the future will lower long-term interest rates today. Lower long-term interest rates will reduce the cost of capital, stimulating investment and economic growth relative to what would be predicted if expectations were ignored."b In the early 1990s, John Taylor, the current Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs, constructed a sophisticated, multi-country model that contained strong linkages between fiscal policy shifts and long-term interest rates. He estimated, for example, that a fiscal policy tightening that amounted to 3 percent of GDP would reduce long-term interest rates by more than 150 basis points in the long run.c Finally, an analysis by Martin Feldstein of Harvard found a strong connection between the federal government's fiscal position and long-term interest rates. Feldstein concluded that "each percentage point increase in the five-year projected ratio of budget deficits to GNP raises the long-term government bond rate by approximately 1.2 percentage points…"(23)d a Council of Economic Advisers, Economic Report of the President, February 1984, page 62.b Council of Economic Advisers, Economic Report of the President, February 1991, page 64. c John Taylor, Macroeconomic Policy in a World Economy (WW Norton: New York, 1993), pages 270-273. It should be noted that Taylor modeled a reduction in government purchases, not a change in taxes. d Martin Feldstein, "Budget Deficits, Tax Rules, and Real Interest Rates," Working Paper No. 1970, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 1986, page 48. |

Furthermore, reports and studies issued by the Reagan Administration, the first Bush Administration, the well-known conservative economist Martin Feldstein, and economist John Taylor, the current Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs, all have emphasized the connection between fiscal policy and long-term interest rates (see box above). In addition, the corporate-led Committee for Economic Development recently issued an analysis emphasizing the link between fiscal policy and interest rates. The CED document states that the robust economic growth of the last half of the 1990s resulted in large part from new investment, which in turn was "catalyzed by pro-investment economic policies — higher national saving from growing budget surpluses and the lower interest rates that those surpluses made possible" [italics added].(24) The CED report also notes that strong economic growth in future years will require significant budget surpluses and that reconsideration of parts of the tax cut not yet in effect may be necessary to secure these surpluses. The bottom line is that unless the major macroeconomic models, as well as the analyses of Alan Greenspan, Robert Rubin, the Committee for Economic Development, the Reagan Administration, the first Bush Administration, Martin Feldstein, and John Taylor, are wrong, the conclusion must be that the tax cut has played some role in the failure of long-term rates to decline over the past year.

The failure of long-term rates to decline impedes economic activity today. It raises the costs of home mortgages and discourages both interest-sensitive consumption and business interest.

Conclusion

The tax cut enacted last year includes some components — such as the rebates sent out last year and some reductions in tax rates — that have already taken effect. Other components, such as the future scheduled reductions in marginal tax brackets and abolition of the estate tax, are not yet in effect. The short-run effect from the tax package as a whole reflects the interplay between these two sets of tax changes.

Analyses of the impact of the tax package on the economy in the short run must carefully distinguish between the tax cuts that have already taken effect and those that are scheduled for the future. The tax cuts that have already taken effect have bolstered the economy, by providing fiscal stimulus in the midst of a recession. The tax cuts scheduled for the future, however, have helped to prevent long-term interest rates from falling, which has restrained economic activity in the short run.

The overall net effect on the economy today of the tax cuts scheduled to take effect in future years is likely to be negative. The adverse impact from higher long-term interest rates is considerably larger than any small, positive impact that may result from increased spending now in response to these future tax cuts. As a result, the tax cuts scheduled to take effect in future years are likely to have made the recession more severe than it would otherwise be.

End Notes:

1. Peter Orszag is the Joseph A. Pechman Senior Fellow in Tax and Fiscal Policy at the Brookings Institution. Robert Greenstein is the Executive Director of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (The views expressed in this piece are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the staff, officers or trustees of the Brookings Institution.) This paper draws upon numerous points and arguments made in William G. Gale and Samara R. Potter, "An Evaluation of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001," forthcoming, National Tax Journal.

2. Matthew Shapiro and Joel Slemrod, "Consumer Response to Tax Rebates," NBER Working Paper 8672, December 2001. It should be noted that the tax cuts already in effect have contributed to higher long-term interest rates, along with the tax cuts not yet in effect, so the net impact on the economy in the short run from the already-implemented cuts is unclear and may not be positive.

3. Lawrence B. Lindsey, "Why We Must Keep the Tax Cut," Washington Post, January 18, 2002, Page A25.

4. Nicholas Souleles, "Consumer Response to the Reagan Tax Cuts," forthcoming, Journal of Public Economics.

5. James Poterba, "Are Consumers Forward Looking? Evidence from Fiscal Experiments?" AEA Papers and Proceedings (1988), pages 413-418.

6. David Wilcox, "Social Security Benefits, Consumption Expenditure, and the Life Cycle Hypothesis," Journal of Political Economy (1989), pages 288-304.

7. Some of the arguments being advanced by opponents of any reconsideration of the tax cut also are internally inconsistent. For example, in arguing that the future tax cuts will not raise interest rates, the Administration and its supporters often invoke an empirically implausible theory under which households offset expected budget shortfalls in future years by saving more today. If households are saving enough today to fully offset the impact of the tax cut on the budget in future years, however, that could not increase their spending today in response to the tax cut. Yet Lindsey and other tax-cut supporters also try to argue that the future tax cuts are spurring more spending now. These two arguments contradict each other.

8. All interest rates are based on constant maturity yields, as calculated by the Federal Reserve, for the week ending on each Friday. The data are available at www.federalreserve.gov.

9. Alan Greenspan, Testimony before House Financial Services Committee, July 18, 2001.

10. Alan Greenspan, Testimony before the Senate Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Committee, July 24, 2001.

11. Alan Greenspan, "The Economy," Remarks at the Bay Area Council Conference, San Francisco, January 11, 2002.

12. Face the Nation, CBS, January 6, 2002.

13. Face the Nation, CBS, January 6, 2002.

14. Alan Greenspan, "The Economy," Remarks at the Bay Area Council Conference, San Francisco, January 11, 2002. It is important to distinguish, as Chairman Greenspan does in his speech, the most recent uptick in long-term interest rates, which are now higher than they were in October 2001, from the fact that long-term rates failed to decline over 2001 as a whole. The more recent increase is likely tied to expectations of faster growth in the future, not the tax cut; the effects of the tax cut were already reflected in long-term rates by October and thus cannot explain the increase in rates since then. But, as Greenspan indicated, the tax cut likely played a significant role in keeping long-term rates as high as they already were in October.

15. Testimony of Alan Greenspan before Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate, July 24, 2001.

16. Novak, Hunt, and Shields, CNN, January 12, 2002.

17. See William G. Gale and Samara R. Potter, "An Evaluation of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001," forthcoming, National Tax Journal.

18. David Reifschneider, Robert Tetlow, and John Williams, "Aggregate Disturbances, Monetary Policy, and the Macroeconomy: The FRB/US Perspective," Federal Reserve Bulletin, January 1999, Table 4. The figures in the text assume the tax cut amounts to between 1.1 and 1.6 percent of GDP. Over the next 10 years, the tax cut costs roughly 1.1 percent of GDP; over the next 75 years, it costs roughly 1.6 percent of GDP (assuming all sunsets are removed). See Richard Kogan, Robert Greenstein, and Peter Orszag, "Social Security and the Tax Cut: The 75-Year Cost of the Tax Cut is More than Twice as Large as the Long-term Deficit in Social Security," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised December 13, 2001.

19. Congressional Budget Office, "Analysis of the President's Budgetary Proposal for Fiscal year 1996," April 1995, pages. 53, 56.

20. B. Douglas Bernheim, "A Neoclassical Perspective on Budget Deficits," Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 1989.

21. Douglas Elmendorf and Gregory Mankiw, "Chapter 25: Government Debt," in Handbook of Macroeconomics (1998), page 1658.

22. Council of Economic Advisers, Economic Report of the President, February 1984, page 62.

23. Martin Feldstein, "Budget Deficits, Tax Rules, and Real Interest Rates," Working Paper No. 1970, National Bureau of Economic Research, July 1986, page 48.

24. Committee for Economic Development, "Economic Policy in a New Environment: Five Principles," September 2001.