How Would Various Social Security Reform

Plans

Affect Social Security Benefits?

An Analysis of the Congressional Research Service

Report

by Kilolo

Kijakazi and Robert Greenstein

In June of this year, Rep. Charles Rangel, ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee, released a Congressional Research Service analysis he had requested on the extent to which three Social Security reform proposals would reduce defined Social Security benefits. The three plans include:

- the bill introduced by Senators Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Robert Kerrey (S. 1792);

- a proposal by the National Commission on Retirement Policy, a panel of Members of Congress and private citizens organized by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (legislation recently introduced in the Senate by Senators Judd Gregg, John Breaux and a few other senators — S. 2313 — and in the House by Reps. Jim Kolbe, Charles Stenholm, and others — H.R. 4256 — is based on the NCRP proposal); and

- a May 1998 proposal by Robert Ball, commissioner of the Social Security Administration under Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon and a member of the 1994-1996 Social Security Advisory Council.

The CRS analysis was not designed to be a comprehensive analysis of all components of these three plans, but rather an assessment of an important issue — the degree to which the "defined," or guaranteed, benefits that beneficiaries would be assured of receiving through the Social Security system would change under the three plans. Accordingly, the study does not examine the retirement income that could be generated by individual accounts, which the three plans all contain in differing forms.(1)

The CRS analysis finds that the Social Security benefits guaranteed under the three plans vary greatly.

- Over the next 75 years, average Social Security benefits would be 23

percent lower under the NCRP plan than under the current benefit structure, 16 percent

lower under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan than under the current benefit structure, and six

percent lower under the Ball plan.(2)

- In other words, the CRS analysis finds that the reduction in guaranteed Social Security benefits would be approximately four times larger under the NCRP plan than under the Ball plan and nearly three times greater under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan than under the Ball plan.

As noted, these figures are 75-year averages. The depth of the reductions in Social Security benefits, as well as the differences among the three plans in the size of the defined benefit reductions, would grow significantly as the years pass. The CRS study reports the results of analyses the Social Security actuaries have conducted of the three plans:

- In 2025, the Social Security benefits received by average wage-earners who retire at age 65 would be 33 percent lower under the NCRP plan than under the current Social Security benefit structure. They would be 11 percent lower under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan than under the current benefit structure and about one percent lower under the Ball plan.

- By 2070, the Social Security benefit reductions would be considerably deeper. The Social Security benefits of average wage-earners retiring that year at age 67 would be 48 percent lower under the NCRP plan than under the current benefit structure, meaning that the guaranteed benefit would be cut about in half. Under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan, the average benefit for an individual retiring in 2070 at age 65 would be reduced by 22 percent, or more than one-fifth.(3) The benefit reduction percentage would remain very small under the Ball plan. (See Table 1 below.)

Source: SSA actuaries estimates, as

reported by CRS |

(Note: Under the NCRP plan, reductions in Social Security benefits would be smaller for low-wage earners than to average-wage earners due to establishment of a new Social Security minimum benefit. According to the CRS study, the reduction in Social Security benefits for a low-wage earner retiring in 2025 at age 65 would be 13 percent under the NCRP plan. The reduction for a low-wage earner retiring at 67 in 2070 would be 31 percent. In conducting this analysis, CRS defined a low-wage earner as one who earned 45 percent of the average wage throughout his work career; currently, 45 percent of the average wage is $12,552.(4))

The CRS study also explains that under the three plans, there would be additional reductions in guaranteed benefits as beneficiaries grow older after retirement, due to changes the plans make in procedures either for computing annual Social Security cost-of-living adjustments or for measuring changes in the Consumer Price Index on which the cost-of-living adjustments depend. The additional reductions are largest in the Moynihan-Kerrey plan, which sets annual cost-of-living adjustments below the Consumer Price Index. The additional reduction is much smaller in the other two plans and smallest in the Ball plan, which would result in the measured CPI being slightly lower but would maintain the cost-of-living adjustment at the CPI level.(5) CRS projects that as a result of these provisions, benefits would decline between age 65 and age 80 by an additional 13 percent under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan, an additional seven percent under the NCRP plan, and an additional four percent under the Ball plan. For those living into their early 90's, the additional benefit reductions would be nearly twice this size.

It should be noted that the figures shown in Table 1 reflect reductions in Social Security retirement benefits. Under the legislation embodying the NCRP and Moynihan-Kerrey proposals, there also would be substantial reductions in Social Security disability and survivors benefits, because the changes in the Social Security benefit formula and cost-of-living provisions would apply to disability and survivors benefits as well as to retirement benefits.(6)

Finally, the study finds that all three plans would fully restore long-term, or 75-year, actuarial balance to the Social Security system. The actuaries of the Social Security system project that the system faces a deficit over the next 75 years equal to 2.19 percent of taxable payroll. The NCRP plan results in a saving of 2.23 percent of taxable payroll over this period. The Moynihan-Kerrey plan saves 2.25 percent of taxable payroll. The Ball plan saves 2.33 percent.

Why Does the Depth of the Benefit Reductions Differ So Much?

These findings raise an important question. What accounts for the CRS finding that the Ball plan would reduce defined Social Security benefits much less than the other two plans while doing as well in closing the 75-year imbalance? There are two principal reasons for this finding.

First, the other two plans reduce the revenue going into the Social Security trust fund and place greater reliance on individual accounts; they essentially divert payroll contributions from the trust fund to individual accounts. The Ball plan, by contrast, does not reduce the revenue going into the trust fund. It adds voluntary individual accounts on top of Social Security but does not divert money from the trust fund for them.

Under current law, the revenue the trust fund is projected to receive over the next 75 years is insufficient to pay the full benefits to which beneficiaries would be entitled during this period. This is what is meant by the statement that Social Security eventually becomes insolvent. Diverting payroll tax revenue from the Social Security trust fund makes the financing shortfall larger and consequently necessitates deeper benefit reductions (or larger payroll tax increases) to put the trust fund back into long-term balance. As the Congressional Research Service explained in an earlier report: "Obviously, if it is projected that the taxes that finance the [Social Security] system are insufficient to pay future promised benefits, earmarking some of them for the buildup of private accounts would make this problem worse. It would mean that to restore the system to solvency future tax increases would have to be larger or benefits cut deeper."(7)

Not surprisingly, CRS found that the NCRP plan, which diverts the most revenue from the Social Security trust fund, contains the deepest Social Security benefit reductions. Among the large benefit reductions in this plan is an across-the-board benefit cut resulting from an increase in the age at which individuals may retire and receive full benefits; the age at which individuals can retire and receive full Social Security benefits would be raised to 70 by 2029 and to approximately 72½ by 2075, a larger increase than any other major plan has proposed.(8) The plan also includes a reduction of one-third in Social Security spousal benefits. (These benefit reductions are described in more detail later in this paper.)

The second reason the Social Security benefit reductions are much more modest under the Ball plan than under the other plans is that the Ball plan invests a portion of the Social Security trust fund reserves in equities. This enables the trust fund to capture the stock market's higher rates of return. The actuaries estimate that the earnings the trust fund would receive from this investment would reduce the 75-year imbalance in the Social Security system by slightly more than half. That, in turn, reduces the benefit reductions or tax increases needed under the Ball plan to restore long-term balance.

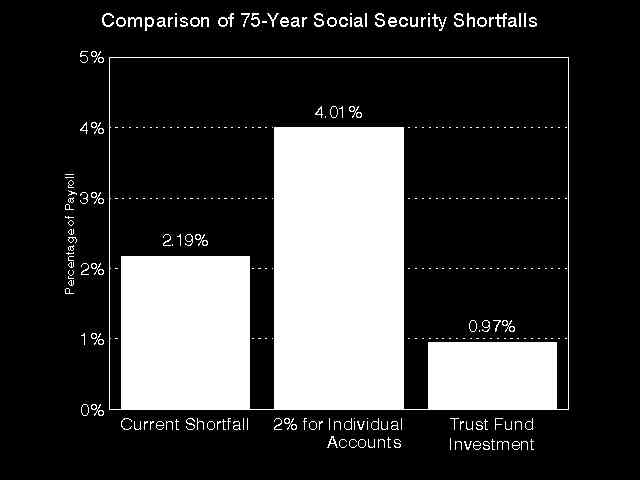

Figure 1 illustrates that redirecting two percent of the payroll tax to individual accounts, as the NCRP plan would do, would enlarge the 75-year shortfall from 2.19 percent of taxable payroll to 4.01 percent, in the absence of other changes. The Figure also shows that investing up to 50 percent of the trust fund in equities, as the Ball plan would do, would reduce the 75-year deficit from 2.19 percent of taxable payroll to 0.97 percent, in the absence of other changes.

For these reasons, Rudolph Penner, a former CBO director now at the Urban Institute who supports the NCRP plan, recently observed that "plans that have the trust fund buying equities generally cut [Social Security] benefits less than plans establishing individual accounts."(9)

The CRS Analysis and Individual Accounts

Proponents of the NCRP plan and the Moynihan/Kerrey bill have criticized the CRS analysis. They fault it for not including the retirement income that would result from the individual accounts the plans contain. They also argue that it is not appropriate to compare benefits under these plans to benefits under the current Social Security system since the current system will not be solvent over the long term. They contend the proposed plans should be compared to a Social Security system revised in a manner that puts it in long-term actuarial balance.

Proposals to divert part of the payroll tax revenue from the Social Security trust fund to individual accounts entail moving partially from a "defined benefit" plan that specifies the payment of particular benefit amounts based on a retiree's earnings history (i.e., from Social Security) to a "defined contribution" plan in which the benefits available to retirees vary greatly. Under a defined contribution plan, benefits depend not only on a beneficiary's earnings history but also on individual investment decisions, the performance of the stock and bond markets (including the state of the markets in the year an individual retires), the real interest rate assumptions used when retirees convert their accounts to annuities, the extent to which funds in individual accounts are consumed by fees that firms charge for managing the accounts (and, where applicable, for converting accounts to annuities at retirement), and other factors.

In weighing options for reforming Social Security, policymakers need to understand the degree to which the defined benefits — that is, the benefits Social Security provides — would be reduced under various approaches, since it is only the defined benefits that retirees are assured of receiving at specified levels. This is the information the CRS study provides.

More comprehensive analyses that factor in the anticipated returns from individual accounts also are needed and should be undertaken. Such analyses are more difficult to conduct, however, than the type of analysis CRS has conducted on the extent to which these three plans would reduce Social Security benefits. Analyses attempting to factor in returns from individual accounts consequently will need to be undertaken with great care. In particular, such studies will need to consider several factors that may have a large impact on the retirement income that individual accounts generate:

Variation in returns from individual accounts: Since individual accounts do not provide defined benefits, the levels of income they generate will differ considerably among beneficiaries and over time. The retirement income from such accounts is likely to offset the reductions in Social Security benefits for some retirees but not others. Retirees who are lucky or wise in their investments should be able to offset the full loss in their guaranteed benefits. Retirees who are unlucky or unwise in their investments — including those who retire and convert their account to a lifetime annuity in a year the market is down — would likely face large reductions in the income they have to live on in their declining years.

A recent GAO report took note of these issues. "There is a much greater potential for significant deterioration of an individual's retirement 'nest egg' under a system of individual accounts," the GAO wrote. "Not only would individuals bear the risk that market returns would fall overall but also that their own investments would perform poorly even if the market, as a whole, did well"(10)

Of particular concern are the returns received by those who lack investment experience. Today, fewer than half of all U.S. households have any investments in the stock market; this lack of experience is likely to make it harder for many to earn solid returns. Moreover, even experienced investors pursuing sound investment strategies can have investments that turn sour and earn below-market returns. The fact that a substantial majority of mutual funds earn rates of return that are below the performance of the S&P 500, a broad measure of the major stocks in the market, is evidence of this fact. These concerns are greatest for plans that allow individuals a wide array of choices in how to invest the funds in their accounts, such as plans that establish accounts similar to IRAs or 401(k) accounts.

Another group likely to face substantial reductions in retirement income under individual accounts are those who must retire early for health reasons but are not sufficiently infirm to meet the stringent Social Security disability criteria, as well as those who have been employed in physically strenuous occupations that are not suitable for someone past their early or mid-60s. Individuals who must retire early would tend to have smaller individual accounts because they would have fewer years of contributing to these accounts. At the same time, they also are likely to have lower Social Security benefits because most of the reform plans that divert revenue from the Social Security trust fund to individual accounts — such as the NCRP plan — raise the normal Social Security retirement age substantially. These plans take this step to shrink Social Security benefit costs enough to help compensate for the large Social Security revenue losses that the diversion of payroll tax revenue to individual accounts entails.

Analyses of the retirement income generated by individual accounts should reflect the range of outcomes these accounts are likely to produce. Simply estimating the average anticipated rate of return for such accounts would obscure the fact that substantial numbers of people would likely receive significantly less income than that from their individual accounts, while others would receive more. Stated another way, such an approach would be problematic because it would fail to reflect the increased risk to beneficiaries that individual accounts carry.

Administrative and Other Costs: Analyses of the retirement income that individual accounts would provide also need to factor in the costs associated with such accounts. Since such costs are paid out of the funds in the accounts, they affect the amount of money available in the accounts to pay retirement benefits.

Private accounts necessarily incur administrative and management fees. Some private account systems also incur costs when account-holders retire and convert the funds in their accounts to lifetime annuities. The individual retirement accounts — or IRAs — and the 401(k) accounts that many Americans possess incur all of these costs. Estimates from two eminent economists, Peter Diamond of M.I.T and Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution, indicate that between 7.5 percent and 30 percent or more of the amounts saved or earned under the individual account systems that would be established under various Social Security privatization proposals would be consumed by administrative, management, and (where applicable) annuitization costs and fees.

Plans that invest Social Security trust fund revenues in equities, rather than diverting trust fund revenue to individual accounts, avoid almost all of these costs. The General Accounting Office recently reported: "Most of the cost of managing an index fund is incurred maintaining thousands of individual accounts. In contrast, the government, as a single investor, would incur negligible costs as a percentage of its assets. Therefore, investing collectively through the government would result in significant administrative savings compared to investing through individual accounts."(11)

This is one of the reasons some Social Security experts, such as Brookings Institution senior fellows Henry Aaron and Robert Reischauer, the former CBO director, favor investing a portion of trust fund reserves in equities as an alternative to individual accounts. Aaron and Reischauer observe that because investing trust fund reserves in equities would avoid such costs, it would generate a higher average net rate of return than individual accounts while exposing beneficiaries to much less individual investment risk.

The Social Security "Baseline"

The other criticism lodged against the CRS analysis by proponents of the NCRP plan and the Moynihan/Kerrey bill is that comparing benefits under reform plans to benefits under the current Social Security benefit structure is inappropriate since the current Social Security system will not be solvent over the long term. They contend that the appropriate standard against which reform proposals should be measured is an altered model of Social Security that includes measures bringing the system into long-term balance.

This criticism of the CRS study is unconvincing. Use of a baseline, or a point of reference where no change has taken place, is common in research. The benefit levels the current benefit structure pays provide an appropriate baseline measure against which to compare the Social Security benefits that various reform plans would provide. To use these benefit levels as a baseline in no way suggests that changes are not needed to restore long-term solvency to the system; it simply provides a readily understandable measure of comparison.

Nor does use of this baseline alter comparisons to each other of the plans CRS examined. The comparative standing of these plans would remain unchanged if CRS had used a different standard. For example, if CRS had used the Moynihan-Kerrey bill as its standard, the NCRP plan would be shown to reduce Social Security benefits relative to the standard while the Ball plan would be shown to raise them.

More important, there is no widely accepted way of altering Social Security to achieve long-term balance that can serve as a baseline. In particular, to compare alternative plans to a policy of restoring balance solely by cutting Social Security benefits may be misleading; that is an option no one is suggesting. Not a single member of the 1994-1996 Social Security Advisory Council recommended such an approach. No proponent of Social Security reform has proposed it.

Furthermore, use of a standard which assumes that balance will be restored solely by cutting benefits could lead to some misunderstanding among the public. Some plans that reduce retirement income below the levels the current benefit structure provides could be shown to increase benefits relative to such a standard; some of the public could mistakenly think this means that such plans would raise benefits relative to the standard-of-living that the current benefit structure provides. If many Americans mistakenly believed such a plan would raise retirement income above the levels the current system provides, they could conclude that no sacrifice would be involved and no increase needed in saving by individuals.

A number of these issues are discussed in more detail below.

Why Do Plans that Reduce or Divert Payroll Tax Revenue Result in Large Reductions in Social Security Benefits?

The principal reason the NCRP and Moynihan-Kerrey plans reduce Social Security benefits much more deeply than the Ball plan does is that they reduce the revenue going into the Social Security trust fund. This deepens the trust fund's financing shortfall and necessitates deeper benefit reductions to eliminate the shortfall. The NCRP plan reduces the revenue going into the trust fund on a permanent basis, while the Moynihan-Kerrey plan reduces trust fund revenue for the next 30 years (and, on average, over the 75-year period used in Social Security projections).

The NCRP plan mandates the permanent diversion of two percentage points of the payroll tax from the Social Security trust fund to individual accounts. The Moynihan-Kerrey bill reduces the payroll tax by two percentage points through 2024 (and by less than two percentage points from 2025 through 2029).(12) The Moynihan-Kerrey plan provides for voluntary individual accounts funded with its one percentage point reduction in the employee share of the payroll tax, along with a mandatory employer matching contribution for any employee establishing such an account, financed by the one percentage point reduction in the employer's share of the payroll tax.

Reducing the revenue going into the Social Security trust fund necessitates deeper reductions in Social Security benefits to restore long-term balance. For example, an analysis by the Social Security actuaries shows that the NCRP plan's diversion of two percentage points of payroll tax revenue to individual accounts increases the deficit in the Social Security trust fund by an amount equal to 1.82 percent of taxable payroll over the next 75 years. The Social Security actuaries project that the current shortfall equals 2.19 percent of taxable payroll over the next 75 years. By deepening the shortfall by 1.82 percent of taxable payroll, the NCRP plan's diversion of two percent of the payroll tax enlarges the size of the Social Security deficit approximately 80 percent. That, in turn, necessitates Social Security benefit reductions about 80 percent larger than otherwise would be needed to restore Social Security to long-term balance.(13)

The NCRP plan achieves these deeper benefit reductions in a number of ways, including the following.

- The NCRP plan raises the age at which individuals can retire and

receive full, rather than reduced, Social Security benefits to a higher age level than any

of the other major plans that have been offered. For example, the plan advanced by the

1994-1996 Social Security Advisory Council that went the farthest in raising the age at

which workers can retire and draw full benefits would raise this age from 65 today (and

eventually 67 under current law) to 70 by 2083. By contrast, the NCRP plan would increase

this age to 70 by 2029 and to approximately 72½ by 2075. The NCRP plan also would raise

the early retirement age, the age at which retired individuals can retire and begin to

draw reduced Social Security benefits, from 62 to 65 by 2029 and to approximately 67½ by

2075.

Raising the age at which individuals can retire and receive full benefits essentially constitutes an across-the-board reduction in Social Security benefits because it reduces benefits not only for those who retire earlier but also for those who remain at work until this age, a point that is not widely understood.(14) Each one-year increase in the age at which full benefits are paid results in a reduction of approximately seven percent in the Social Security benefits that an average worker receives over his or her retirement years.(15)

In addition, increasing from 62 to 65 the age at which individuals can retire and begin to draw reduced Social Security benefits would be particularly burdensome for those who are unable to work until 65 either because they are in poor health during their early 60s (but are not sufficiently infirm to meet the stringent Social Security disability criteria) or because they have been employed in physically strenuous occupations in which they cannot remain employed until 65.

- The NCRP plan also makes major changes in the Social Security benefit computation formula. Under the current, progressive formula, Social Security benefits equal 90 percent of the first $477 of a worker's average monthly wage over his or her work-years, 32 percent of the next $2,875 of a worker's average monthly wage over his or her work years, and 15 percent of the remainder of a former worker's average monthly wage.(16) The NCRP plan would, over time, lower these 32 percent and 15 percent "replacement rates" to 21.36 percent and 10.01 percent, respectively, which would constitute a large benefit reduction. A significantly smaller percentage of the wages and salaries many workers earned would be replaced by Social Security benefits when they retired. This formula change alone reduces benefits for a worker whose average wages are $40,000 in 1998, and whose wages rise in subsequent years at the same rate as average wages in the economy, by 22 percent.

- In addition, the NCRP plan proposes to reduce the benefit Social Security provides to spouses of primary wage-earners; the spousal benefit would be lowered from 50 percent of the primary wage-earner's benefit, as under current law, to 33 percent of that benefit. Many spouses thus would experience a benefit reduction of up to one-third, on top of the NCRP plan's other benefit reductions. (Some members of the 1994-1996 Social Security Advisory Council also proposed to reduce the spousal benefit, but they used the savings from this proposal to help finance an increase in the benefits that Social Security pays to widows and widowers so as to provide more adequately for widows, who face poverty at very high rates.(17) In 1996, some 39 percent of elderly widows — about two in every five — had incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line.(18) Reducing spousal benefits without raising widows' benefits would reduce benefits principally among women.)

Since the Ball plan does not divert trust fund revenue to fund individual accounts, it does not need Social Security benefit reductions of this magnitude. As noted above, the Ball plan further shrinks the size of the benefit reductions or tax increases needed to restore Social Security to long-term balance by investing a portion of Social Security reserves in the equities markets and thereby capturing the higher rates of return these markets provide. This is essentially the same strategy that state and private pension funds use.

Estimating the Effects of Various Plans When Income From Individual Accounts is Added

The CRS analysis does not purport to be a comprehensive analysis of all components of the three plans it examines, but rather an assessment of the changes made in the defined, or guaranteed, benefits that retirees would be assured of receiving through Social Security. Analyses also are needed that include projected returns from individual accounts. Undertaking such analyses is not easy or straightforward.

To factor in benefits from individual accounts one must make assumptions regarding investment behavior, stock market performance, the expectations that firms selling annuities have concerning what inflation and interest rates will be in coming years, and other factors. Since future earnings are unlikely to mirror past earnings exactly, all such projections are subject to a wide range of error. More important, projected rates of return from individual accounts generally are averages; the actual benefits that individuals would derive from such accounts would vary substantially from the estimated average figures, with some beneficiaries garnering higher rates of return and others receiving lower rates of return.

Many low-income earners may receive relatively low rates of returns from their investments. Low-income families tend to have little experience with retirement accounts or with investing in stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. They would be more likely than experienced investors to make poor investment choices. Experience with 401(k) accounts suggests they also would be likely to invest quite conservatively, probably out of fear of losing the limited resources they have. In a June 17, 1998 House Ways and Means Committee hearing on individual accounts, several witnesses testified that much of the public lacks sufficient knowledge about investing to manage such accounts well.(19)

When estimating the retirement income that individual accounts would generate, there is no easy way to factor in the potential for a substantial segment of the public — and in particular, those with below-average earnings — to invest unwisely or too conservatively. One possible approach is to show ranges for the levels of retirement income and rates of return that individual accounts would generate. Estimates that simply show projected average rates of return on individual accounts, rather than ranges, tend to oversimplify this matter. Another possible approach is to attempt to estimate the percentage of individuals likely to secure rates of return lower (or higher) than the average rate of return. Such variations are particularly important in light of the fundamental purpose of social insurance, which is to assure the retired, the disabled, and survivors a certain basic income.

The Year of Retirement Can Greatly Affect a Beneficiary's Level of Retirement Income Under A System of Individual Accounts There also are a number of other ways in which investment risk would affect the retirement income an individual would receive under a system of individual accounts. For example, Gary Burtless, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has shown that under such a system, the amount of the monthly annuity for an individual who converts his or her individual account to an annuity at retirement could vary greatly not only as a result of the investment choices a worker has made but also as a result of the state of the stock market in the year the individual retired. If an individual retires and converts his or her account to an annuity in a year in which the stock market is very high, the individual is likely to receive a more ample annuity check. But if the individual has the misfortune to retire and annuitize when the market is down, the individual can be faced with a meager income for the rest of his or her life. Burtless' research shows that if workers retiring in the 1960s and 1970s had deposited funds in individual accounts throughout their careers, with the money invested in stock index funds, an average male worker who retired and converted an individual account to an annuity in 1976 would have received a monthly benefit for the rest of his life that was only a little more than half as large as the monthly benefit an average male worker who retired and annuitized seven years earlier, in 1969, would have received. |

Even more difficult is the task of estimating how the stock market will perform in coming decades. Given the dizzying increases in the market in recent years, using market performance for a period that includes these years to predict future performance may generate estimates of rates of return for individual accounts that prove to be too high. The ratio of stock prices to corporate earnings has climbed will above its traditional range, which raises questions about how much further the equities markets will rise. No one knows the answer to this question. In recent congressional testimony, Rudolph Penner, who backs the NCRP plan, acknowledged that for this reason, "considerable uncertainty surrounds the assumption regarding what can be earned" through investment in equities.(20) (It may be recalled that only three decades ago, in the 1970s, the market preformed poorly and lost a large share of its value.)

One set of factors that can more readily be taken into account in estimating the retirement income that individual accounts may generate involves the costs associated with these accounts, including administrative and management fees, costs under some plans of converting funds in these accounts to annuities that pay a monthly benefit until death, and costs under some plans of the transition from Social Security to private accounts. All private account plans entail some or all of these costs. Since the costs are generally paid from the accounts, they reduce the retirement income the accounts generate. Estimates that do not reflect such costs are not valid.

The administrative costs that must be paid from the funds in individual accounts are the expenses that investment firms incur in handling the accounts, conducting marketing efforts to attract investors, communicating with their investors, record-keeping, and corporate overhead. The fees these firms charge to account-holders also include a profit margin; no one can expect private firms to handle such accounts for free or at a loss. The administrative costs for IRAs currently range from $35 to $45 per account per year.(21) For private defined contribution pension plans, administrative costs vary by the number of participants in the plan and have been estimated to range from approximately $50 per year per participant for a plan with 10,000 or more participants to nearly $290 for a plan with 15 or fewer participants.(22) Flat-rate costs of this nature are most disadvantageous to low-wage workers, since these charges consume a larger percentage of the investments in small accounts than of the investments in larger accounts. In addition to these administrative costs are investment management fees that firms charge for investing the funds in these accounts and shifting the funds as account-holders direct.

Two eminent economists, Peter Diamond of MIT and Henry Aaron of the Brookings Institution, have studied administrative and management fees associated with IRAs and 401(k) plans.(23) They estimate that by retirement, costs for individual accounts established on an IRA or a 401(k) model would consume, on average, about 20 percent of the funds otherwise deposited in or earned by the accounts. As Diamond explains, a one percent annual average charge on funds in such an account consumes, over a 40-year work career, 20 percent of the funds in the account.(24) Based on the most recent financial data on mutual funds, a one percent annual charge is a conservative estimate. Lipper Analytical Services reports that in 1997, the average charge on no-load stock funds equaled 1.21 percent of amounts invested in the funds, while the average charge on front-load stock funds equaled 1.25 percent.(25) Moreover, the 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security estimated an annual charge of one percent on assets in privately managed individual accounts.(26)

Financial Securities Analyst Explains That Administrative Costs Can Substantially Reduce Returns From Accounts In testimony July 24 before the Subcommittee on Finance and Hazardous Materials of the House Commerce Committee, Joel M. Dickson, Senior Investment Analyst with the Vanguard Group, explained the large role that administrative costs can play in lowering rates of return that individual accounts can provide, especially for the smaller-than-average accounts of workers with below-average earnings. Dickson stated: "Much of the recent debate on individual accounts has centered around how Social Security participants can earn higher rates of return — like those experienced in the private financial markets. Unfortunately, there is often a large gap between the assumed market return on an investment and the actual return realized by investors. The reason? Cost... What may seem to be a relatively small cost difference over a short period of time can become an enormous difference over a long investment horizon.... "Consider a $1,000 investment in two equity funds; one earns a market return of 10%; the second earns only 8%, which represents the market's return reduced by an all-too-realistic total cost of 2% (arising from charged expenses and portfolio transaction costs). After the first year, the difference in account values between the two options is only $20. Of course, a participant investing over the course of their working lifetime must consider much longer time horizons. Over 40 years, the first fund soars to $45,000. The second fund, earning 2% less per year, grows to $22,000 — less than half what the market earned.... "The key pricing variable for private accounts is the average account size. To the extent that costs of servicing the accounts could not be covered by asset-based management fees, other charges — like account maintenance fees — are likely. One of the criticisms often made about privately-managed, individual accounts is that lower-income workers may not be as financially savvy, resulting in lower average returns. I think a bigger issue is that lower-income and part-time workers will have small account balances, potentially subjecting them to higher fees because asset-based revenue cannot begin to cover the costs of maintaining these accounts. Thus, they are likely to earn lower returns than higher-income workers that make the same investment choices for reasons unrelated to financial market sophistication." |

The amounts consumed would generally be larger than 20 percent for smaller-than-average accounts and smaller than 20 percent for large accounts. This means the retirement income that individual accounts modeled on IRAs or 401(k) plans would generate would be about 20 percent smaller on average than the income would be without these fees and costs. It also means that estimates of the retirement income that IRA-type or 401(k)-type accounts would generate will overstate this income by approximately 20 percent on average if the estimates do not reflect these fees and costs.

Costs of Converting Accounts to Annuities

A sizable additional cost also would be incurred under plans that feature private accounts modeled on IRAs or 401(k) plans — the cost of converting the funds in a worker's account to a lifetime annuity when the worker retires. These costs cover a company's marketing expenses, commissions to agents, investment costs, overhead, and profits.

The leading study on this issue indicates that the fees charged for converting an account to an annuity at retirement consume, on average, approximately five to ten percent of the retirement savings of an individual purchasing a $100,000 annuity.(27) In other words, the insurance company would take five to 10 percent of the amount in the retiree's account to cover its costs and profits, with the amount of the monthly annuity check being based on the remaining 90 percent to 95 percent of the funds in the account. (These annuitization costs can vary by as much as 15 percent across insurance firms. A retiree would need to be fairly astute in selecting the best company from which to purchase an annuity. Many people do not have sufficient investment expertise to make the wisest choices in purchasing annuities.)

In addition, prices for annuities are generally raised to cover the company's risk of incurring added costs due to "adverse selection." Adverse selection refers to the probability that people with longer-than-average life expectancies will be more likely to purchase lifetime annuities than people with shorter-than-average life expectancies. Insurance companies cover themselves for the costs of paying lifetime annuities to people who may live to very old ages. The resulting increase in the price of annuities has been estimated to reduce the value of retirement savings being converted to an annuity by an additional 10 percent.

Totaling all of these costs and charges, Henry Aaron concludes that the administrative and management costs plus the costs of converting funds in these accounts to annuities would consume between 30 percent and 50 percent of the amounts saved in IRA-type or 401(k)-type individual accounts. These are very large amounts and indicate why analyses of plans that include individual accounts need to reflect estimates of these costs in their computations. (Estimates of rates of return from individual accounts issued by privatization proponents such as the Heritage Foundation tend to ignore such costs and are not valid as a result.)

Costs Under the Thrift Savings Plan Model

Diamond also has examined likely administrative costs for individual accounts modeled on the Thrift Savings Plan. The individual accounts the NCRP plan would create are based on this model. The costs for this type of account would be considerably lower but would still be significant. Diamond estimates that the costs of administering this type of account would consume approximately 7.5 percent of the funds in an average worker's account (as distinguished from the 20 percent cost Diamond and Aaron estimate for plans with IRA or 401(k) type accounts), reducing the retirement benefits these accounts would pay by that percentage.(28) Under the NCRP plan, the percentage by which accounts would be reduced to cover administrative costs would be the same for all accounts without regard to their size.

Investment of Trust

Fund Reserves in Equities Likely Both the Ball plan and a separate plan designed by former Congressional Budget Office director (and now Brookings senior fellow) Robert Reischauer and Brookings senior fellow Henry Aaron would invest a portion of Social Security trust fund assets in broadly indexed funds. Such approaches would tend to generate higher rates of return than plans that divert a portion of payroll tax revenue to individual accounts, because investing a portion of the trust funds in the equities markets does not entail the administrative costs, management fees, and (in some cases) annuitization costs involved in systems with nearly 150 million individual accounts. If individual accounts and trust fund reserves invested in index equity funds were both to earn the average market rate of return — but the retirement benefits the individual accounts paid had to reflect the administrative costs, management fees, and, where applicable, annuitization costs these accounts must pay — the investment of trust fund reserves in the market would necessarily generate a higher net rate of return. Investing a portion of trust fund reserves in the market also pools the risk of investing in the market so no single individual has to face the threat of large investment losses. For these reasons, Reischauer, Aaron* and

a number of other economists have concluded that this approach is likely to yield higher

rates of return at lower risk to beneficiaries than a system of individual accounts. |

Annuitization costs under a plan such as the NCRP proposal are less clear. The NCRP plan requires a minority of retirees to annuitize. Others could annuitize but would not have to do so; those who did would have several options regarding how to annuitize. Some individuals who annuitized would likely incur large annuitization costs. Some others likely would not convert their accounts to annuities. Those who did not annuitize would not be able to withdraw all their funds at once; there would be limits on the amounts they could withdraw. The annual amount an individual would be allowed to withdraw would be based on his or her life expectancy. As the individual grows older, the maximum withdrawal allowed would decrease to stretch the savings left in the account over the years expected to remain in the individual's life. If an individual with a modest account lived to a very old age, the withdrawals could eventually become very small. This stands in contrast to Social Security benefits, which do not decline in amount as an individual grows older but rather increase to keep pace with inflation.

(There also is some question as to the feasibility of using the Thrift Savings Plan model for a system of 140 million or 150 million individual accounts held by workers of millions of employers. Francis X. Cavanaugh, the former head of the Thrift Savings Plan and a former Reagan Administration Treasury official, recently testified that managing such a system would require 10,000 highly trained federal employees and stated that in his view, "... it would be impossible to establish cost-effective TSP-type PSAs [personal savings accounts] for the Social Security system."(29))

The CRS study provides a useful analysis of the effects of the three plans on the defined benefits that Social Security provides. The data in the study demonstrate that plans that reduce or divert Social Security payroll tax revenue from the trust fund to individual accounts entail deeper reductions in Social Security benefits than plans that do not reduce trust fund revenue. The data also illustrate the fact that plans that invest a portion of Social Security trust fund assets in equities can restore Social Security to long-term balance with smaller Social Security benefit reductions than other plans because such an approach boosts trust fund revenues.

Subsequent studies should attempt to incorporate the effects of the individual accounts that various plans establish on the income that retired workers would receive. Such analyses will need to take into account the average amounts the individual accounts are projected to earn, the risk that account-holders would face and the wide variation in retirement income that consequently could result, and the costs and fees that would affect the benefit payments these accounts can make.

End Notes

1. The analysis also does not examine changes in payroll taxes or the effects of a few features of the plans, such as proposals in some plans to eliminate the Social Security earnings test.

2. These estimates reflect the effects of provisions in the Ball and Moynihan/Kerrey plans to increase the taxation of Social Security benefits, since such measures are a benefit reduction from the beneficiary's perspective. The figures subsequently cited for the percentage benefit reductions for individuals retiring in 2025 and 2070, however, do not include the taxation-of-benefit provisions; the memorandum prepared by the Social Security actuaries that CRS used in conducting its analysis did not include the effects of those provisions when examining benefit reductions for individuals retiring in given years. This is the principal reason that while the Ball plan would reduce total Social Security benefits an estimated six percent over the next 75 years, the benefit reduction for an individual retiring in 2025 is estimated at one percent. (Ball subsequently presented a proposal to the House Ways and Means Committee in testimony on June 3, 1998 that dropped the taxation-of-benefits provision included in the Ball proposal analyzed here.)

3. The memoranda prepared by the Social Security actuaries that CRS used in conducting its analysis do not provide data on the percentage reduction in benefits for workers retiring at age 67 under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan.

4. Individuals with earnings lower than 45 percent of the average wage would face smaller Social Security benefit reductions in the NCRP plan if they worked a sufficient number of years. The minimum benefit for a very low-wage worker under the NCRP plan could exceed the benefit the worker would receive under current law.

5. Under the Moynihan-Kerrey plan, the annual cost-of-living adjustment would be set one percentage point below inflation as measured by the CPI. The Ball plan would keep the cost-of-living adjustment at the CPI, but directs the Bureau of Labor Statistics to update the market basket on which the CPI is based no less frequently than every five years instead of every 10. CRS estimates that would be equivalent to reducing the cost-of-living adjustment by three-tenths of one percentage point per year. The legislation on which the NCRP plan is based calls for development of a new Social Security CPI that would be lower than the regular CPI to the extent that the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates the regular CPI contains "substitution bias." If BLS concluded that the measures it announced in April 1998 to reduce substitution bias in the CPI have addressed this matter and no such further bias remains or can be estimated, the Social Security CPI that the NCRP plan establishes would be set .33 percentage points below the regular CPI each year. This level of detail on how the cost-of-living adjustments would work under the NCRP plan was not available when the Social Security actuaries prepared the estimates on which the CRS analysis is based; as a result, the CRS analysis may somewhat overstate the degree to which this aspect of the NCRP plan would result in additional benefit reductions as retirees grow older.

6. Some sponsors of the legislation embodying the NCRP plan have stated that it does not change disability benefits. Such statements are not correct and appear to reflect some misunderstanding on the part of these sponsors of the effect of their legislation on disability benefits. The NCRP plan changes the benefit formula for computing a beneficiary's primary insurance amount (or PIA), on which Social Security benefits are based for retirement benefits, disability benefits, and survivors benefits alike. A forthcoming Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis will explain this matter in more detail.

7. "Ideas for Privatizing Social Security," Congressional Research Service, April 6, 1998.

8. The age at which individuals may retire and receive full Social Security benefits is commonly referred to as the "normal retirement age." That term, however, is a misnomer; the majority of Social Security beneficiaries retire and begin drawing benefits before this age. What is commonly called the "normal retirement age" is simply the age at which full, rather than reduced, Social Security benefits are paid.

9. Testimony of Rudolph G. Penner before the Senate Budget Committee, July 23, 1998.

10. General Accounting Office, Social Security: Different Approaches for Addressing Program Solutions, July 1998, p. 6.

11. General Accounting Office, "Social Security Financing: Implications of Stock Investing for the Trust Fund, the Federal Budget, and Economy," statement of Barbara D. Bovbjerg before the Senate Special Committee on Aging, April 22, 1998.

12. The Moynihan-Kerrey plan begins to raise the payroll tax in 2025 and restores the tax rate to its current level by 2030. The plan also would begin to raise the payroll tax rate slightly above the current level in 2045 and continue raising it until 2060. At that time, the combined employee and employer shares of the payroll tax would be one percentage point above the current level.

13. The NCRP plan offsets a modest portion of the revenue loss by shifting from the Medicare trust fund to the Social Security trust fund the share of the revenue from partial taxation of Social Security benefits that currently is deposited in the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust. Shifting this revenue would deepen the long-term fiscal imbalance in the Medicare trust fund, however, which is more serious than the long-term imbalance in the Social Security trust funds. When all of its changes in trust fund revenue are considered, the NCRP plan deepens the trust fund shortfall by 1.39 percentage points of payroll, or 50 percent.

14. Under current law, with the age at which full benefits are paid set at 65 and scheduled to rise to 67 by 2022, workers who retire at 62 (or 63 or 64) receive lower monthly benefits for the rest of their lives in recognition of the fact that their benefits will be spread over more years. Conversely, those who do not retire until age 70 receive higher monthly benefits for the rest of their lives because they will draw benefits for fewer years. Under proposals to raise to 70 the age at which full benefits are paid, however, those who retire at 70 would receive the standard benefit that now goes to those retiring at 65; they would no longer receive an enhanced benefit for workers who do not retire and begin drawing benefits after the age at which full benefits are paid. Raising the age at which full benefits are paid thus essentially constitutes an across-the-board cut; if the age is raised to 70, those retiring at 70 lose benefits along with those who retire in their 60s.

15. "Increasing the Eligibility Age for Social Security Pensions," Testimony of Gary Burtless, senior fellow, The Brookings Institution, before the Senate Special Committee on Aging, July 15, 1998. When the age at which individuals can retire and draw full benefits is raised to 70 under the NCRP plan, individuals would be able to retire at 65 and begin drawing reduced Social Security benefits, just as individuals today can retire and begin receiving reduced benefits at 62. Those electing the early retirement option would receive reduced Social Security benefits for the rest of their lives. Under the NCRP plan, individuals could retire and begin to make withdrawals from their individual accounts before age 65 if there were enough funds in the accounts to provide monthly payments at least equal to the poverty line.

16. In computing these average monthly wage figures, the Social Security Administration indexes wages earned in years before a worker's retirement by changes in average wages in the U.S. economy in the intervening years.

17. Under the recommendation these Advisory Council members made, the widow or widower of a deceased worker would receive 75 percent of what the couple's combined benefit would have been, rather than receiving only the worker's benefit (or only the widow or widower's own benefit, if larger), as under current law. Report of the 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security, Volume I: Findings and Recommendations, January 1997

18. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Survey, 1996, March 1997.

19. Testimony of Teresa Tritch, senior editor of Money magazine, and Ric Edelman, head of Edelman Financial Services, before the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Social Security of the Committee on Ways and Means, June 18, 1998.

20. Testimony of Rudolph G. Penner, senior fellow, the Urban Institute, before the Senate Budget Committee, July 23, 1998.

21. Remarks by Philip Lussier, State Street Global Advisors, before the National Commission on Retirement Policy, Social Security Working Group, February 25, 1998.

22. Edwin C. Hustead, "Trends in Retirement Income Plan Administrative Expenses," Pension Research Council Working Paper, 96-13, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1996.

23. Statement by Peter Diamond, AARP-Concord Coalition Debate on Social Security, Albuquerque, July 27, 1998; Peter Diamond, "The Future of Social Security for this Generation and the Next: Proposals Regarding Personal Accounts," testimony before the Subcommittee on Social Security of the House Committee on Ways and Means, June 18, 1998; testimony of Henry J. Aaron before the Senate Committee on the Budget, July 23, 1998.

24. Diamond explains that with a one-percent annual charge on holdings in accounts, a dollar deposited in an individual account in the first year of a 40-year work career will be subject to the one percent fee 40 times, while a dollar deposited in the final year before retirement will be subject to the fee once. On average, dollars in the account will be subject to the one percent annual charge 20 times, so approximately 20 percent of the amounts deposited or earned by the account will be consumed by these charges. Diamond also notes that in Chile, costs consume approximately 20 percent of the amounts in individual accounts, with the percentage being higher in Great Britain and Argentina.

25. See Robert McGough, "Robust Fund Industry Isn't Lowering Fees," Wall Street Journal, May 14, 1998.

26. The Advisory Council assumed an annual change of one percent on accounts established under the Personal Security Accounts proposal, a proposal that diverted five percentage points of the payroll tax to individual accounts. Since many of the administrative costs involved in managing private accounts are fixed costs that do not vary with the size of the account, this suggests that the average charge could be larger than one percent per year on the smaller individual accounts that would be established under plans using IRA-type or 401(k)-type accounts that divert two or three percentage points of the payroll tax into these accounts rather than five percent.

27. Olivia S. Mitchell, James M Porterba, and Mark J. Washawsky, New Evidence on the Money's Worth of Individual Annuities,"Cambridge, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 1997. Also see Aaron, op. cit.

28. Administrative costs for TSP equaled approximately $20 per participant in 1997, which equaled about 3.75 percent of what would be the average worker's deposit into a private account under the NCRP plan. As Aaron, Diamond, and former Thrift Savings Plan head Francis Cavanaugh have testified, using this model for the accounts of 140 million to 150 million workers employed by millions of employers would entail significantly higher costs in percentage terms than the cost of operating the Thrift Savings Plan for employees of a single employer, the U.S. Government. The TSP's economies-of-scale would not be available due to the existence of millions of separate employers. In addition, many costs associated with operating the Thrift Savings Plan are borne by the federal agencies in their role as employer rather than by TSP itself (e.g., responding to employees' questions); such costs would almost certainly not be imposed upon private employers under an individual accounts plan based on the TSP model. These costs would have to be borne by the entity operating the accounts system and defrayed through charges on the accounts. In addition, federal agencies transmit the relevant data to TSP electronically, while many private employers submit data on paper; that would further increase the costs for the entity administering the accounts (as well as the risk of errors in maintaining accounts records).

29. "Statement of Francis X. Cavanaugh before the Subcommittee on Social Security of the House Ways and Means Committee, June 18, 1998.

| Additional related reports: |

Publication Library | Center Staff | Search this site

Job Opportunities | Internship Information | Top Level