Revised August 14, 2002

Revised August 14, 2002WHAT OMB’S MID-SESSION REVIEW TELLS US

— AND WHAT IT OBSCURES

by Richard Kogan and

Robert Greenstein

| PDF

of full report

Related Reports |

| If

you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined

text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the

document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

In February

2001, the Administration, through the Office of Management and Budget,

projected that:

- federal budget surpluses would total $5.6

trillion over the ten-year period from 2002 through 2011;

-

there would be surpluses both in the Social

Security trust fund ($2.5 trillion over ten years) and in the rest of the federal budget ($3.1 trillion over ten

years);

-

those projected surpluses would grow larger with

every passing year; and

Like OMB, the Congressional Budget

Office also projected a $5.6 trillion surplus over the period 2002-2011. While CBO expressed great uncertainty about

its projections, however, and emphasized the wide range of possible outcomes, the

Administration seemed more certain. OMB

director Mitchell Daniels stated at the time: “There is vastly more than enough

room [for the tax cut]…the budget is built on very conservative and cautious

assumptions.” Daniels and OMB dismissed

concerns that due to the inherent uncertainty of budget projections, surpluses

of the magnitude they were projecting might not materialize. They said that the greatest risk to the

accuracy of their forecasts was that they might be understating government revenues, not overstating them. Their views were reflected in a ringing

declaration in the President's February 2001 budget: “There is ample room in

the Administration’s budget to pay off debt as far as possible, to reduce taxes

for American families, to fund program priorities, and still have roughly $1.0

trillion [outside of the Social Security Trust Fund] for Medicare modernization

and to meet other programmatic and contingency needs as they arise.”

President Bush similarly stated at

the time, “We’re going to prove to the American people that we can pay down

debt, fund priorities, protect Social Security, and there will be money left

over, which we strongly believe ought to be passed back to taxpayers. … We can

proceed with tax relief without fear of budget deficits, even if the economy

softens. …”

Now, 17 months later, the OMB

“mid-session review” released on July 15 shows that $3.9 trillion of the $5.6

trillion ten-year surplus has already disappeared. Moreover, in the budget it issued this February,

the Administration proposed tax cuts and spending increases totaling an

additional $1.3 trillion over the ten-year period (and far more in the decade

after 2011); as the mid-session review indicates, the Administration continues

to support these proposals. According to

OMB’s own projections, this would leave the budget outside Social Security in

deficit through 2012 (and probably for decades thereafter).

In short, OMB’s

new budget projections are dramatically different from its projections of 17

months ago. Some of the change in the

budget picture reflects increases in security spending. Most of the change, however, is due to other

factors — the large tax cut enacted last year (which the new OMB data show to

have caused 38 percent of the reduction in the projected surplus over ten

years), a less buoyant economy than had been forecast, and downward revisions

in the forecasts of how much tax revenue the economy generates for any given

level of economic performance. It is

evident that the Administration’s forecast of 17 months ago was too optimistic

about the state of the economy and revenue collections, too dismissive of the

impact that emergencies and unforeseen factors could have on the budget, and,

as a consequence, too sanguine about the nation’s ability to address various

priorities and still have enough left over for the Administration’s tax cut.

Analysis of the

Administration’s new mid-session budget indicates that it suffers from some of

the same types of shortcomings:

-

OMB’s new

estimates themselves are likely to prove much too rosy. While other analysts — including the Senate

Budget Committee Republican staff — project a further increase in the deficit

in fiscal year 2003, OMB now projects a substantial reduction in the deficit in 2003.

This rosy forecast apparently is based partly on an assumption that the

stock market will be higher in 2002 than in 2001 and produce an increase in the

capital gains revenues that are paid with 2002 tax returns filed next

spring. In light of recent developments

in the stock market, such an assumption does not seem likely. In addition, the Administration’s new budget

projects an economy larger in size every year through 2012 than the

Administration itself projected earlier this year, before the stock market declined.

(This has the effect of boosting projected revenues.) The new budget also omits or understates the

costs of various policies that the Administration itself is advancing, such as

the President's foreign aid initiative and the prescription drug proposal that

the House of Representatives passed with the White House’s endorsement and

support. In addition, the budget omits

the cost of several virtually inevitable tax reduction measures, such as the

cost of extending an array of popular tax credits that expire every few years

and are always extended on a bipartisan basis and the cost of addressing the

looming problems in the individual Alternative Minimum Tax.

As a result, the new budget substantially overstates

expected government revenues, while substantially understating expected

government costs.

-

OMB’s

press office issued figures substantially understating the cost of last year’s

tax cut. The press release that OMB

disseminated with the mid-session review asserted, in a widely reported statement,

that last year’s tax cut accounts “for less than 15 percent of the change” in

the ten-year surplus projections since February 2001. Data in the mid-session review show, however,

that the tax cut actually accounts for 38

percent of the deterioration, which makes it the single largest factor in the

shrinkage of the surplus. These data

show that the 15 percent figure applies only to the shrinkage of the surplus

over the two-year period 2002-2003, not to the deterioration over ten years. OMB failed to correct this error for two

weeks (until the day after the original version of this CBPP analysis was

issued on July 25), when OMB quietly excised the erroneous sentence without acknowledging

that the previous, widely reported version of its press release was inaccurate. (After being stung by media criticism, OMB

modified the press release again on August 7 to include a statement that the

initial press release contained errors, but without explaining what the errors

were.) Both the Administration’s rosy

scenario and its understatement of the effect of the tax cut on the budget made

it appear as though room remains for substantial additional tax cuts.

-

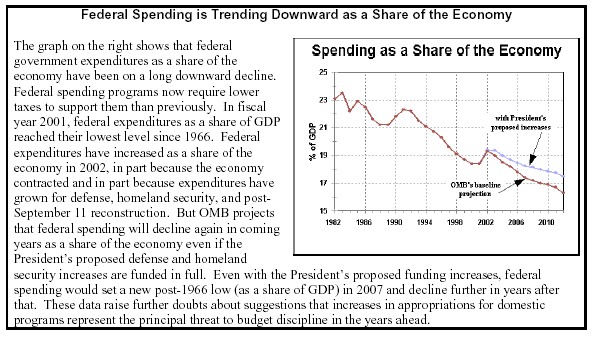

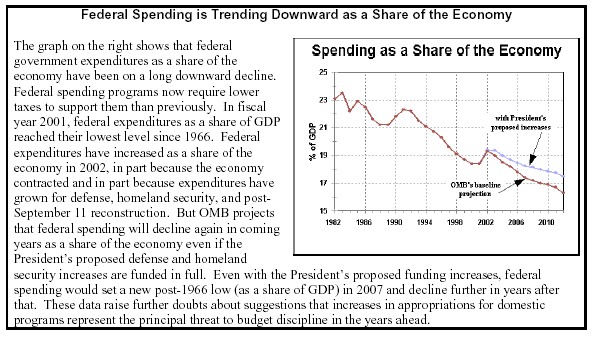

OMB

focuses on domestic appropriations as a threat to fiscal discipline even though

defense and homeland security will grow significantly while domestic

appropriations are likely to shrink in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. In discussing the long-term need to

control federal spending, OMB has implied that appropriations for domestic

programs are, or will be, the cause of any long-term budget problems. Yet the bulk of the appropriations increases

enacted since the issuance of the $5.6 trillion surplus estimates in early 2001

— and the overwhelming share of appropriations increases under consideration

for 2003 — are for defense and homeland security, not for domestic programs. In fact, both the overall funding level that the

Administration has requested for domestic appropriated programs (other than

homeland security) for 2003 and the somewhat higher level approved by the

Senate Budget Committee would constitute reductions

for these programs (in “real” or inflation-adjusted terms) below the 2002 level.

The recent disclosures of

misleading corporate accounting practices and rosy corporate financial

projections are now taking a serious toll on the stock market and beginning

to affect consumer confidence. At this

juncture, it is important for government to avoid the temptation to engage in

accounting maneuvers that overstate likely revenues, understate likely

expenditures, and advance proposals whose full costs are concealed by slow

phase-ins or other delays in implementation.

Table 1

Shares of the Reduction in the Projected

Ten-Year Surplus, 2002-2011

Changes

from February 2001 baseline to July 2002 baseline

|

What

OMB July 12 Press Release Claimed

|

What

OMB Data Show

|

|

Recession

|

67%

|

All economic reestimates (incl. recession)

|

10%

|

|

Technical reestimates

|

no mention

|

Technical reestimates

|

33%

|

|

“Security and the war”

|

19%

|

All enacted spending increases

|

18%

|

|

Last year’s tax cut

|

15%

|

Last year’s tax cut

|

38%

|

|

Tax cuts in “stimulus” bill

|

no mention

|

Tax cuts in “stimulus” bill

|

2%

|

|

TOTAL

|

100%

|

TOTAL

|

100%

|

|

Source: OMB.

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. |

This analysis examines the

mid-session review and the questions it raises in some detail. It starts with an examination of factors that

make the budget projections too optimistic.

It then examines the causes of the change in the budget picture since

February 2001, based on OMB’s own data.

Finally, it looks at the implication in the mid-session review that

Congressional efforts to increase appropriations for domestic programs

constitute the principal threat to fiscal discipline.

A Rosy Scenario

“Rosy

Scenario” is the name given to projections the Reagan Administration issued in

1981, which showed that the large Reagan tax cuts would generate such strong economic

growth that the budget would turn from deficit to surplus despite the loss of

revenue from the tax cuts and the Administration’s proposed increases in defense

spending. Reality was not kind to Rosy;

as a share of the economy, federal deficits were higher from 1982 through 1986

than in any year since World War II, and the 1983 deficit exceeded the peak

deficits of the Great Depression.

In

retrospect, it now seems clear that President George W. Bush’s first budget also

was built on what turned out to be a rosy scenario. The new projections in the mid-session review

follow such a path, as well.

-

Unrealistically

low deficit forecasts. In the

mid-session review, OMB projects that the deficit will drop substantially between

2002 and 2003, falling from $165 billion to $109 billion even if all of the

President’s proposals for additional defense increases and tax cuts are enacted. In contrast, the Republican staff of the Senate

Budget Committee and most outside experts project an increase in the deficit between 2002 and 2003.

- An

economic forecast that is rosier than the forecast OMB issued earlier this

year. OMB projects that the size of

the economy will be larger in every year

through 2012 than OMB projected in February of this year. This more optimistic economic projection

serves a convenient purpose. In the new

forecast, OMB reduced its February projection of revenues by almost $800

billion through 2012 for “technical” reasons to reflect the recent large

declines in revenue collections and the consensus that previous budget

forecasts had overstated the amount of revenue that will be collected for any

given level of economic activity. But

OMB accompanied this reduction in revenue for technical reasons with new

economic assumptions that are sufficiently rosy that they enable OMB to show an

offsetting increase of $700 billion

in its revenue forecast for “economic” reasons.

In other words, OMB’s economic projections are sufficiently rosy that

they cancel out almost all of the reduction in the revenue forecast that had to

be made for technical reasons.

- Apparent

increases in projected capital gains revenue. In its July 12 press packet on the

mid-session review, OMB noted that tax revenues have declined more than can be

explained by the tax cuts and the recession.

OMB reported that the “2002 receipts drop is notably larger than the

decline in economic growth — an 8 percentage point difference” after adjusting

for the effects of tax legislation. OMB

explained that this revenue shortfall is likely the result of “a dramatic

decline in net capital gains realizations.”

In other words, this revenue shortfall appears to be due primarily to a

sharp drop in capital gains income and thus in the capital gains taxes

collected on such income. Consistent

with this widely accepted view, between February and July of this year, the

Treasury reduced its estimate of fiscal year 2002 revenues by $105 billion for

“technical” reasons — that is, for reasons such as lower capital gains revenues

than had been projected, rather than because of changes in the size of the

economy or the enactment of legislation.

Experts believe that capital gains

tax revenue will drop further in fiscal year 2003. Capital gains tax collections in fiscal year

2003 will largely reflect the capital gains income shown on 2002 tax returns,

which will be filed next winter and spring.

And capital gains income for tax year 2002 is expected to fall because

of the significant declines in the stock market, with the S & P 500 index

now down more than 25 percent this year.

Yet OMB’s mid-session review appears to assume that capital gains

revenue will increase in fiscal year

2003 above the fiscal year 2002 level. For that to occur, the stock market would generally

have to produce a stunning turnaround by December 31, essentially recovering

its losses for the year and then some, so that people who sell stock by then

(and pay capital gains taxes on it next winter and spring) will be selling at a

gain. Given the current state of the

stock market, it seems highly questionable for OMB to be counting on stock

prices taking off this much in the immediate future. This dubious assumption is a key reason that

the mid-session review shows a substantial reduction in the deficit in fiscal

year 2003 when most experts expect the deficit to grow larger.

-

History does

not support OMB. A shrinking deficit

in 2003 is inconsistent with historical experience. After both the 1981 and the 1991 recessions,

the deficit increased in each of the next two fiscal years. History shows that changes in budget outcomes

lag behind changes in the economy.

The

mid-session review also understates likely future deficits by omitting the costs

of a number of expensive policies that the President supports and Congress is virtually

certain to enact.

- Prescription

Drugs. The President has endorsed

the House-passed prescription drug plan, and OMB Director Daniels has stated,

“The President has been very plain in saying he will treat the House budget

resolution, the only one that got passed, as the budget for this year.” The House prescription drug plan costs $350

billion over ten years, which also is the amount the House budget resolution

allots for the plan. But the Administration’s

mid-session budget continues to show only $190 billion over ten years for this

legislation. That is the amount the

President originally proposed but has since apparently abandoned.

- Expiring

Tax Credits. The budget continues to

omit the cost of extending an array of expiring tax credits that enjoy

overwhelming bipartisan support and have always been extended in the past, most

recently in the “stimulus” bill. Except

for the Research and Experimentation tax credit, the President's current budget

does not propose any further extensions of these tax credits. That omission enables OMB to leave out the

costs of these credits in the years following their expiration. Everyone expects the Administration will

support continued extension of the credits, and there is little question that

Congress will continue to extend the credits whenever they are scheduled to

expire, as it has done on a bipartisan basis for many years. The Administration’s omission of most of the

cost of these credits in years after 2003 also is noteworthy in light of the

Administration’s view that allowing a tax credit or other tax-reducing measures

to expire on schedule constitutes a “tax increase.”

- The

Alternative Minimum Tax. The budget

also omits the very large costs of providing relief from the individual

Alternative Minimum Tax. The

Administration’s budget proposes to make permanent the tax cuts that expire in

2010 but fails to include the cost of extending a certain-to-be-renewed provision

of last June's tax cut that is scheduled to expire at the end of 2004. This is the provision that prevents the

individual AMT from exploding into the middle class.

Because the Administration's budget omits extension of this

provision, the revenue numbers in the budget are based on the assumption that

the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT will swell from 1.4 million in 2001

to 39 million by 2012. (Buried in one of

the budget books is an acknowledgment that the revenue numbers assume that 39

million taxpayers — one of every three in the nation — will be subject to the

AMT by 2012.) There is no possibility

the Administration or Congress will allow this to happen. The Administration clearly intends to propose

addressing this problem before the current AMT relief provision expires in 2004,

and there is no question that AMT relief will pass. OMB Director Daniels recently acknowledged in

congressional testimony that the AMT problem will need to be addressed. Joint Tax Committee estimates indicate that

the cost of resolving this problem will amount to several hundred billion

dollars over the next ten years.

Moreover, assuming that a swollen AMT will be in effect in

2011 and 2012, as the OMB projections do, helps the Administration in a second

way — it substantially reduces the amounts that OMB shows as being the costs in

2011 and 2012 of extending the tax cuts scheduled to expire in 2010. Since the AMT is assumed to affect 39 million

taxpayers by 2012, it is assumed to cancel out a significant share of the tax

cuts in those years, sharply lowering the amounts that OMB prints in the budget

for the cost of extending the tax cut.

- Foreign

Aid. The budget also omits the costs

of the Millennium Challenge Account, which the President announced in March as

a proposal to increase assistance to developing nations. The President has proposed spending another

$5 billion per year on foreign aid by 2006

How the Budget Has Changed Since February 2001

When OMB

projected a $5.6 trillion, ten-year surplus in February 2001, the surplus

seemed almost too big to squander. In this

section of the analysis, we use the detailed budget data that OMB released in

conjunction with the mid-session review to examine how, according to OMB’s

numbers, the budget outlook for the next ten years has changed since early 2001.

What OMB said. The material that OMB distributed to the

press on July 12 made striking claims about the causes of the deterioration of

the surplus. The OMB press release asserted:

“…the recession erased two-thirds of

the projected ten-year surplus (FY2002-11).

The costs of security and war lowered the projections 19%. The tax cut, which economists credit for

helping the economy recover, generated less than 15% of the change.”

OMB’s own

numbers, however, show that these assertions are incorrect. The percentages cited in the OMB press release

are the figures for the two-year period

2002-2003 or for 2002 only, not for the

ten-year period 2002-2011. The

figures for the ten-year period are very different. The tax cut phases in over time, and its

costs mount markedly as the decade progresses.

It accounts for a much larger share of the deterioration of the surplus

over the next ten years as a whole than of the deterioration just in 2002 and

2003. (This error apparently originated with an

overzealous public relations person in OMB or the White House. The error was so flagrant, however, that OMB was

clearly aware of it, and as described below, senior Administration officials were

questioned about it within a few days. Nevertheless,

OMB did not drop the erroneous paragraph from its July 12 press release until

July 26, after the initial release of this Center analysis calling attention to

the error, and did not amend the press release to note that the original version

contained errors until August 7.)

In the short run, the recession is

indeed an important factor in the shrinkage of the surplus. But over the long run, this cannot possibly be

the case — OMB is not predicting a ten-year recession. (CBO previously concluded that a mild

recession would decrease projected ten-year surpluses by less than $150 billion,

which suggests that 90 percent or more of the $3.9 trillion shrinkage of the

surplus since January 2001 is not attributable

to the recession.)

What the OMB data actually

show. As noted, the projected $5.6

trillion, ten-year surplus projected by OMB in February 2001 has shrunk by $3.9

trillion. The following tables present

what the OMB data reveal to be the reasons for this deterioration.

As Table 2 shows, the tax cut

accounts for 16 percent of the deterioration of the surplus in 2002 and 2003,

but will account for nearly half of the shrinkage of the surplus in 2010 — or

nearly as much as all other factors combined.

Over the ten-year period as a whole, the tax cut accounts for 38 percent

of the shrinkage of the surplus, which is more than spending increases for defense,

homeland security, and domestic programs and changes in the economy combined. The tax cut is the single largest factor

responsible for the deterioration of the surplus over the ten-year period. (Moreover, the tax cut appears to be at least

2½ times as costly over the next ten years as the war on terrorism.)

Under tough questioning in a

Congressional hearing on July 17, Glenn Hubbard, Chairman of the President's Council

of Economic Advisers, admitted that the tax cut accounts for about 40 percent

of the deterioration in the surplus over the next ten years and that the 15-percent

figure applies only to the first year or two.

Table 2

The Surplus Has Shrunk by $3.9 Trillion since February 2001

Difference between

February 2001 baseline and July 2002 baseline, in billions of dollars

|

|

|

2002-2003 avg.

|

2010

|

2002-2011 total

|

|

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

|

Changes in the economic

forecast

|

51

|

12%

|

31

|

7%

|

386

|

10%

|

|

Changes due to “technical”

reestimates

|

185

|

45%

|

144

|

31%

|

1,282

|

33%

|

|

Legislation enacted to

date:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last year’s tax cut

|

68

|

16%

|

218

|

47%

|

1,491

|

38%

|

|

|

Tax cuts in stimulus bill

|

44

|

11%

|

1

|

0%

|

71

|

2%

|

|

|

Program increases

|

67

|

16%

|

73

|

16%

|

689

|

18%

|

|

Total reduction in the

surplus

|

414

|

100%

|

467

|

100%

|

3,920

|

100%

|

|

Source: CBPP calculations

from OMB data. Figures may not add due

to rounding. |

A second way to analyze the OMB

data is to distinguish those matters over which policymakers have little

control — the economy and changes in “technical factors” that affect revenue

collections and the costs of certain programs such as Medicare — from changes

in the surplus caused by legislation that Congress passed and the President

signed. Congress and the President

should not be held responsible for changes in the budget that result from

unanticipated changes in the performance of the economy or from technical

reestimates of taxes or expenditures, although they can be charged with

adopting too rosy a scenario to begin with.

Congress and the President are

responsible for the legislation they enact.

According to OMB, legislation has

reduced the projected 2002-2011 surplus by $2.3 trillion since February 2001

and accounts for the majority of the $3.9 trillion surplus shrinkage. Examination of the OMB data shows that this

$2.3 trillion deterioration was due predominately to the tax cut, as shown in

Table 3, below.

-

The OMB data show that last year’s tax cut

accounts for 38 percent of the deterioration of the surplus in 2002 and 2003 that

has been caused by legislation. This is the same size as the proportion of

the deterioration caused by increases in spending for defense, homeland

security, and domestic programs combined.

Moreover, when the tax cuts in the stimulus package are added in, tax

cuts are found to account for a total of 63 percent of the deterioration in

2002 and 2003 that has been caused by legislation.

-

Concerns over the nation’s fiscal health primarily

revolve not around the deficits projected in 2002 and 2003, but around the

fiscal picture for subsequent years. The

OMB figures show that last year’s tax cut accounts for 66 percent, or about

two-thirds, of the deterioration in the surplus over the next ten years that is

due to legislation. By 2010 the tax cut

will account for 75 percent of the deterioration in the surplus due to legislation,

and if last year’s tax cut is made permanent as the President has requested, by

2011 it will account for about 80 percent of the deterioration in the surplus due

to legislation.

Table 3

Legislation Has

Shrunk the Surplus by $2.3 Trillion since February 2001

In billions of dollars

|

|

2002-2003 avg.

|

2010

|

2002-2011 total

|

|

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

|

Last year’s tax cut

|

68

|

38%

|

218

|

75%

|

1,491

|

66%

|

|

Tax cuts in stimulus bill

|

44

|

25%

|

1

|

0%

|

71

|

3%

|

|

Program increases

enacted to date

|

67

|

38%

|

73

|

25%

|

689

|

31%

|

|

Total cost of legislation

to date

|

179

|

100%

|

292

|

100%

|

2,251

|

100%

|

|

Source: CBPP calculations

from OMB data. Figures may not add due

to rounding. |

Still another way to analyze the

OMB data is to assess what portion of the surplus deterioration is due to the

shrinkage in revenues (including both the shrinkage due to tax cuts and the

shrinkage due to economic and technical factors), what proportion is due to

increased spending on defense and homeland security, and what portion is due to

domestic spending increases.

-

Over the ten-year period, reductions in revenues

account for 87 percent of the overall shrinkage of the surplus.

-

By contrast, increased expenditures for defense

and homeland security account for 8 percent of the deterioration of the

surplus.

-

Increased expenditures for domestic and

international programs (other than homeland security programs) account for 5

percent of the shrinkage.

These figures, shown in Table 4, include the increase in

interest payments caused by reduced revenues and higher spending (see footnote 6). Over the ten-year period from 2002 through 2011,

OMB now projects that interest payments on the debt will be about $950 billion higher than it projected in

February 2001.

Table 4

Combined Effect of Legislation and Reestimates on Projected Surpluses:

Change in OMB Baseline Projections from February 2001 to July 2002

In billions of

dollars

|

|

2002-2003 avg.

|

2010

|

2002-2011 total

|

|

Reduced revenues

|

77%

|

95%

|

87%

|

|

Increased costs of defense

and homeland security

|

9%

|

6%

|

8%

|

|

Increased costs of

domestic and international programs

|

14%

|

-2%

|

5%

|

|

Total reduction in the surplus

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

Source: CBPP calculations from OMB data.

Figures include the extra interest payments due to each of the causes listed. Figures may not add due to rounding. |

These figures cast doubt on the statements made in early

2001 that the federal government had so much excess revenue that it could

nearly eliminate the national debt, increase spending on defense, education and

other needs, provide a prescription drug benefit, enact the Administration’s

entire tax cut, and still have a cushion of close to $1 trillion left over for

contingencies.

Misleading Analysis of Appropriations

Some OMB material

accompanying or contained in the mid-session review appears designed to exert pressure

on Congress to limit the level of annual appropriations. According to OMB, the programs whose funding

is determined through annual appropriations (known as “discretionary” programs)

are the main threat to future surpluses.

On page 9 of the mid-session review, OMB purports to show that the

President has requested a hefty 10 percent funding increase for these programs

for 2003 (primarily for defense and homeland security) but that the budget plan

the Democratic majority of the Senate Budget Committee approved in April contains

a 12.3 percent funding increase even while it scales back the President’s

defense request. According to the OMB

presentation, the Senate Budget Committee plan includes large increases in

domestic programs.

OMB’s

portrayal of the Administration’s proposed discretionary funding increases is

misleading, and its portrayal of the spending reflected in the Senate Budget

Committee plan is incorrect. Table 5

shows the levels of discretionary funding (or appropriations) requested by the

President for fiscal year 2003, as well as the comparable levels included in

the congressional budget resolution approved by the Senate Budget Committee in

April. This table clarifies a number of

issues and shows that the mid-session review overstates the size of both the funding

increases that the Administration is proposing for discretionary programs and

the increases contained in the Senate Budget Committee plan.

The

overstatements reflect a curious maneuver on OMB’s part. In calculating the percentage increases in

discretionary funding both in its budget and in the Senate plan, OMB has

omitted from the 2002 levels the funding that was enacted last fall in response

to the terrorist attacks. But in calculating

the discretionary funding levels that would be provided for fiscal year 2003

under both the Administration’s budget and the Senate Budget Committee plan,

OMB has counted the continuation of

this anti-terrorism funding. By

comparing 2002 funding levels that omit anti-terrorism funding with proposed

2003 levels that include such funding, OMB has artificially inflated the

increases between 2002 and 2003.

In addition,

OMB claims in the mid-session review and accompanying press materials that the Senate

Budget Committee plan would reduce the President’s 2003 defense request. In fact, the Senate plan includes the full

amount the President requested for 2003 for defense (and for homeland

security).

Finally,

while the overall discretionary funding level in the Senate plan does exceed

that in the Administration’s budget — with virtually all of the difference

being due to the higher levels the Senate plan contains for domestic

discretionary programs such as education, veterans’ medical care, and natural

resources — the Senate’s so-called “increase” in discretionary funding turns

out simply to be a smaller reduction

in domestic discretionary programs than the Administration has proposed. The mid-session review gives the impression

that the Administration has proposed adequate but restrained increases for

domestic discretionary programs while the Senate Budget Committee plan calls

for unsustainably large jumps in such funding. As Table 5

shows, the Administration has, in fact, proposed to reduce overall fiscal year 2003

funding for domestic discretionary programs outside of homeland security by $15

billion below the CBO baseline (i.e., $15 billion below the 2002 level adjusted

for inflation).

Table 5

Funding For Discretionary

Appropriations, 2002 and 2003

In billions of dollars

|

|

|

Defense, homeland

security, and international

|

Domestic (except

homeland security)

|

Total

|

|

FY 2002 funding level enacted last year

|

$389

|

$321

|

$710

|

|

FY 2003 funding levels:

|

|

|

|

|

|

CBO baseline (2002 adj. for inflation)

|

400

|

333

|

732

|

|

|

President’s request (CBO est.)

|

442

|

318

|

759

|

|

|

Senate Budget Committee

|

442

|

326

|

768

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Increase or decrease, 2002 to 2003:

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

$

|

%

|

|

|

President’s request (CBO est.)

|

+52

|

+13.4%

|

-3

|

-1.1%

|

+49

|

+6.9%

|

|

|

Senate Budget Committee

|

+53

|

+13.5%

|

+5

|

+1.6%

|

+58

|

+8.1%

|

|

Increase or decrease from CBO’s baseline:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

President’s request (CBO est.)

|

+42

|

+10.5%

|

-15

|

-4.6%

|

+27

|

+3.7%

|

|

|

Senate Budget Committee

|

+43

|

+10.6%

|

-7

|

-2.0%

|

+36

|

+4.9%

|

|

|

Source: CBO. Figures may not add due to rounding. |

The Senate Budget Committee plan would set overall funding

for domestic discretionary programs other than homeland security some $7

billion below the CBO baseline level. The

current dispute between the Administration and the Senate thus essentially

concerns not domestic funding increases but rather the depth of domestic funding

cuts. It is not valid to imply that

smaller cuts (which the Administration portrays as larger increases) pose a serious

threat to future budget discipline. That

threat lies elsewhere.

To be sure,

total funding for discretionary

programs — including the defense budget and the homeland security initiatives —

would rise significantly under both the Administration’s budget and the Senate

Budget Committee plan. But this is

entirely because of the large defense and homeland security increases that both

budget plans contain.

End Notes:

Two elements of the mid-session review

suggest that OMB expects a noticeable bounce-back in capital gains revenues in

2003. The first is that OMB forecasts individual

income tax revenues to grow by 10.4 percent from 2002 to 2003 even while it

forecasts the economy to grow by 5.5 percent.

(These figures include both inflation and real growth). Revenue growth exceeds economic growth by

such large margins only when the vast bulk of income growth is concentrated at

the top of the income scale, as occurs when the stock market booms.

The

second element is buried in OMB backup material that shows how the revenue

forecast has changed since February 2002.

In that material, OMB shows a permanent “technical” decrease in the

amount of revenues it now projects, compared with its projection of February

2002. “Technical” changes in budget

estimates are changes that are not caused by legislation and not directly

related to the level of growth in the overall economy. A lower projection of capital gains revenues

is a prime example of such a technical change, and OMB has expended

considerable ink explaining (correctly) that capital gains income cannot grow

as it did in the past if the stock market is flat or falling. Given the stock market’s performance so far

this year, one would expect to see large “technical” reductions in the revenue

forecast for 2002 and even larger reductions for 2003 (since capital gains revenues

in any fiscal year are paid on capital gains realized in the prior calendar

year), relative to the projection OMB issued in February 2002. But OMB shows a smaller downward technical reestimate for 2003 than it does for

2002, implying a big bounce-back in the stock market by the end of this year.

See also “President's

Budget Uses Accounting Devices And Implausible Assumptions to Hide Hundreds of

Billions of Dollars in Costs,” Center on Budget, February 5, 2002, available at https://www.cbpp.org/2-4-02bud.htm.

“Daniels Repeats Bush Veto Threat on

Approps,” Roll Call, July 18, 2002, p 3.

The statement that the tax cut is responsible for only 15 percent of the

deterioration in the surplus is also misleading in two other ways. First, the 15-percent figure excludes the

costs of the corporate tax cuts enacted in the stimulus bill. Second, OMB calculated the 15-percent figure

as a share of the total change from

the February 2001 baseline through the (assumed) enactment of the President's

2003 budget. Under this approach, the

additional tax cuts proposed by the President and his requested 2002

supplemental appropriations bill and 2003 defense increases are used to make

the deterioration attributable to last

year’s tax cut appear smaller. Under

this method, the bigger the new tax cuts and defense increases that the

President requests, the smaller last year’s tax cut appears as a share of the

total deterioration.

The statement in the OMB press release that the recession caused two-thirds of

the deterioration of the surplus is problematic for a second reason as well:

not only does it apply only to 2002, but it also mixes together temporary

revenue shortfalls caused by the recession with temporary and permanent revenue

shortfalls stemming from such reasons as the overvalued stock market, which

cannot be attributed simply to the effects of a temporary recession.

Projections of the surplus or deficit can deteriorate for a specific reason

(e.g., a revenue shortfall, a tax cut, or program increases). Each such change also produces a change in

the amount of interest projected to be paid on the federal debt. For instance, OMB estimates that last year’s

tax cut directly cost $1.2 trillion over the ten-year period 2002-2011; this

means that the surplus will be $1.2 trillion smaller than projected in February

2001 for that reason alone. The smaller

surplus means that federal debt will be higher in each year than was projected

in February 2001, and the Treasury consequently must pay more interest on the

debt than was projected. OMB estimates

that last year’s tax cut will cause the Treasury to pay $305 billion more

interest on the debt over the ten-year period, bringing the total ten-year cost

of the tax cut to $1.5 trillion. OMB’s

approach of attributing interest costs to legislation that directly costs money

is sound and is followed in the tables in this analysis.

An analysis issued by the Senate Budget

Committee majority staff similarly finds that 38 percent of the reduction in

the ten-year surplus is attributable to last year’s tax cut, using the same

comparison of OMB data as we provide in this analysis. The House Budget Committee minority staff makes

a different comparison. Rather than

comparing OMB’s February 2001 baseline with OMB’s new baseline, the HBC

minority compares OMB’s February 2001 baseline with the President’s current budget proposal. Because that budget calls for an additional $1.3 trillion in costs over

the ten-year period 2002-2011, last year’s tax cut is a smaller percentage of

the total possible deterioration in the surplus. Specifically, the $1.5 trillion cost of the

tax cut over 2002-2011 is 29 percent of a $5.2 trillion deterioration. But, as the House Budget Committee minority

staff points out, the President’s budget proposes significant additional tax

cuts (and also reflects the tax cuts enacted this spring in the “stimulus”

bill), and these tax cuts should be taken into account as well. In total, OMB numbers show that enacted and

proposed tax cuts constitute 37 percent of the total $5.2 trillion

deterioration that will occur if the President’s budget is enacted by

Congress.

“Tax Cut ‘Bit Player’ in Revised Deficit Forecast, CEA Chairman Says,” Daily Tax Report, Bureau of National

Affairs, July 18, 2002, p.

G-8. The Daily Tax Report article quotes Hubbard as saying, “In the first

year, 15 percent sounds about right. … Over the longer period of time, a 40

percent number sounds about right.”

The figures shown in this table are CBO’s

March estimates of the President’s February budget request. CBO has not undertaken an estimate of the

President’s mid-session review, but the mid-session review includes only tiny

changes to the President’s budget request for discretionary 2003 funding, so

CBO’s March figures continue to apply.

The

President’s February budget omitted any request for supplemental appropriations

for 2002 even though OMB was at work preparing such a request at that time. While the President’s budget now reflects his

request for a 2002 supplemental appropriations bill, we do not include it in

CBO’s 2002 figures in Table 5 because this table is intended to compare the

President’s 2003 request with the 2002 amount enacted last year. If we had

included the pending 2002 supplemental funding in the base 2002 level, the

increase from 2002 to 2003 — which Table 5 shows is smaller than OMB asserts — would

appear smaller still.