SENATE FINANCE PROPOSAL MASKS FULL

COST:

Chairman's Mark is Nearly as Large as Bush Tax Cut in Second Ten Years

by Richard Kogan, Joel Friedman, and Robert Greenstein

Summary

| View PDF version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The "Chairman's Mark" released on May 11 by Senators Charles Grassley and Max Baucus officially meets the Congressional budget resolution target of $1.35 trillion over 11 years. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the mark will cost $1.348 trillion over this period, including $98 billion in the first two years. This may lead some to assume the package is significantly smaller than the Bush Administration's $1.6 trillion basic tax package. (1)

The proposal does scale back several provisions the President proposed, such as the reduction in the top income-tax rate. But it enlarges other provisions the Administration proposed and adds a number of new tax cuts not contained in the Bush plan. The principal mechanism the proposal uses to comply with the budget resolution target is not a significant overall shrinkage of the Administration's package, but rather an array of devices that artificially hold down costs in the ten years the resolution covers but yield little or no savings over the long term. For example:

- The proposal delays until 2009, 2010, or 2011 the date on which many of the major tax cuts it includes would become fully effective.

- Certain provisions in the mark would "sunset" — or expire — in the middle of the ten-year budget period, thereby excluding a portion of their costs from the estimate. Such provisions almost surely will be extended rather than die; not to extend them would constitute a tax increase in the year after their expiration.

- The proposal fails to include other tax-cut measures virtually certain to be enacted in the near future, such as the extension of various popular expiring tax credits and legislation to address the problems in the Alternative Minimum Tax.

If the proposal were not designed in such a way as to artificially lower its cost by leaving out various tax-cut measures whose enactment is inevitable and sunsetting others measures before 2011, it would cost $1.7 trillion over the ten years from 2002 to 2011, more than the amount the Congressional budget plan allows. This is likely to be a more accurate estimate of its cost over this period.

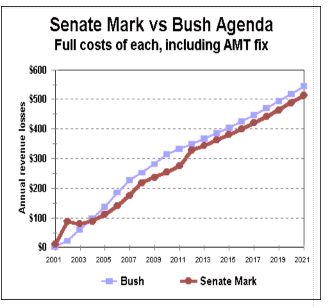

Moreover, because many provisions of the Chairman's Mark are heavily backloaded, the full cost of the policies reflected in the proposal can be seen only by examining the proposal's cost in the second ten years, from 2012 to 2021. This is the first period in which all of the measures in the bill would be fully effective. The bill would cost approximately $4.1 trillion during the second ten years, far more than its cost during the first ten years and close to what the Bush plan would cost in the second ten years. (The Bush plan is estimated to cost $4.4 trillion in the second ten years.)

The Chairman's Mark is more backloaded than the basic Bush tax plan and omits more costs that ultimately will be incurred. As a result, while official cost estimates show that the Chairman's Mark costs 18 percent less than the basic Bush tax package over the first decade, our calculations suggest that, during the second decade, the cost of the Chairman's Mark will be only 6 percent less than the full costs of the basic Bush tax plan.

The Chairman's Mark Backloads Most of its Major Tax Cuts

Under the Chairman's Mark, the estate tax would not be repealed until 2011, the same year it would be repealed under the House-passed bill (H.R. 8) and two years later than it would be repealed under the President's budget. Because it takes a year or two to settle an estate, the full costs of estate-tax repeal would not appear until after 2011 — that is, until after the ten-year budget window had ended. In addition, the bill's major marriage-penalty relief provisions would not be fully effective until 2010 and would not even start phasing in until 2006. Other backloaded provisions include: the expansion of the child credit, which would be fully effective only in 2011; the increase in the amount that taxpayers can contribute to Individual Retirement Accounts, which also would not become fully effective until 2011; the increase in the starting point for the phase-out of itemized deductions for higher-income taxpayers and full repeal of the personal exemption phase-out for higher-income taxpayers, which would not be implemented until 2009; and the upper-bracket rate reductions, which would not take full effect until 2007. (See box.)

The Chairman's Mark Uses the AMT to Hold Down Costs Artificially

The proposal makes the growing problems surrounding the Alternative Minimum Tax more severe. It also understates the cost of a number of its tax-cut provisions by unrealistically assuming that the AMT will cancel out several hundred billion dollars of tax relief the bill is designed to provide.

Provision |

Year Fully Effective |

Comments |

Repeal estate tax |

2011 |

Full costs show up only after 2011 |

Increase IRA contribution limits |

2011 |

$5,000 limit reached in 2011 |

Additional IRA catch-up contributions |

2011 |

$2,000 add-on reached in 2011 |

Expand child credit |

2011 |

$1,000 credit reached in 2011 |

Marriage penalty relief: |

||

Expand 15% bracket |

2010 |

Starts to phase in only in 2006 |

Increase standard deduction |

2010 |

Starts to phase in only in 2006 |

Increase employee contribution limit for 401(k) and similar retirement plans |

2010 |

$15,000 limit reached in 2010 |

Repeal personal exemption phase-out |

2009 |

No phase in, repeal in 2009 |

Raise starting point of itemized deduction phase-out |

2009 |

No phase in, takes effect in 2009 |

Reduce upper-bracket income tax rates |

2007 |

Rates reduced in 2002, 2005, and 2007 |

- The proposal provides limited — and largely temporary — AMT relief; it increases the AMT exemption amount but ends that provision after 2006. As a result, much of the limited AMT relief the bill provides would terminate after 2006.

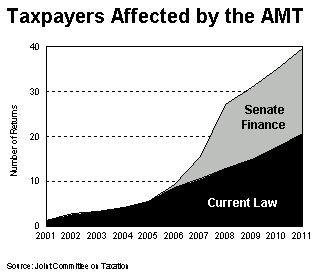

- The Joint Tax Committee projects that under the bill, the number of taxpayers affected by the AMT would explode over the coming decade, climbing to nearly 40 million taxpayers by 2011. This is more than 25 times the number of taxpayers the AMT will affect in the current year. The Joint Committee projects that a swollen AMT would cancel significant amounts of the tax relief that the bill is commonly thought to provide, thereby lowering the bill's stated cost.

Congress will not allow the AMT to explode in this manner, however. It ultimately will act to prevent these tax cuts from pushing millions more taxpayers under the AMT. Such action will cost tens of billions of dollars on an annual basis. By leaving permanent AMT reform out of the Chairman's Mark except for a few modest measures, the framers of the proposal were able to shrink the official cost estimate of the proposed tax cuts. But since the problems in the AMT eventually will be addressed, the actual cost of the pending legislation ultimately will be considerably greater than the figure reflected in the current cost estimate.

The Chairman's Mark Fails to Extend Several Expiring Tax Credits That Are Virtually Certain to Be Extended

Although President Bush proposed to make permanent the Research and Experimentation tax credit — and there is near-universal agreement that this popular tax credit, scheduled to expire in 2004, will be renewed — the Chairman's Mark lacks a measure to extend it. That enables the $47 billion cost of extending this credit throughout the decade — a cost that is included in the Bush plan and ultimately will be incurred — to be left out of the bill's cost estimate. The Chairman's Mark also omits measures to extend most of the other popular tax credits that are scheduled to expire in the next few years. These credits virtually always are extended; most of them are certain to be renewed in the years ahead. Extending these credits through 2011 will add another $36 billion in cost. This cost, too, is not reflected in the cost estimate for the current legislation.

The Chairman's Mark Adds to the List of "Tax Extenders" by Sunsetting Some of its Tax-cut Provisions Before 2011

The proposal sunsets certain provisions. These include: an

"above-the-line" deduction for qualified higher education expenses, which

sunsets after 2005; a non-refundable credit for moderate-income workers to encourage

retirement savings, which sunsets after 2006; and the increase in the AMT exemption

discussed above, which also sunsets after 2006. It is highly unlikely these tax provisions

will be allowed to expire in 2005 or 2006. They almost certainly will be extended. Not

counting the increase in the AMT exemption (which is considered as part of the AMT

discussion here), extending these new Senate provisions throughout the decade would add

$32 billion in costs. Stated another way, sunsetting these provisions artificially lowers

the bill's cost by another $32 billion.

The proposal sunsets certain provisions. These include: an

"above-the-line" deduction for qualified higher education expenses, which

sunsets after 2005; a non-refundable credit for moderate-income workers to encourage

retirement savings, which sunsets after 2006; and the increase in the AMT exemption

discussed above, which also sunsets after 2006. It is highly unlikely these tax provisions

will be allowed to expire in 2005 or 2006. They almost certainly will be extended. Not

counting the increase in the AMT exemption (which is considered as part of the AMT

discussion here), extending these new Senate provisions throughout the decade would add

$32 billion in costs. Stated another way, sunsetting these provisions artificially lowers

the bill's cost by another $32 billion.

The Chairman's Mark Ultimately Costs Almost as Much as the Basic Bush Tax Plan

The tax cut proposed by President Bush is backloaded in that most provisions are phased in slowly over five years, and the repeal of the estate tax is phased in over eight years. But, as previously explained, the Chairman's Mark is somewhat more backloaded than the Bush tax cuts: while we estimate the Bush tax cuts to cost 2.3 times as much in the second decade as in the first decade, we estimate the Chairman's Mark to cost 2.4 times as much. (The method for calculating these costs is discussed in the box on page 6.)

Because the Senate bill is even more backloaded than the Bush budget, the costs in the second ten years come close to the costs of the Bush plan in these years. Those who hoped the lower target for tax cuts in the congressional budget would lead to a substantially less costly tax cut may find themselves disappointed.

Bush "Agenda" proposal |

Senate Bill |

Reduction below Bush Plan |

|

Official estimate of costs in the first decade |

1,638 |

1,338 |

-18% |

Full cost in first decade (including AMT relief) |

1,902 |

1,692 |

-11% |

Full cost in second decade (including AMT relief) |

4,401 |

4,139 |

-6% |

Ratio of costs in second decade to costs in first decade, as a measure of backloading |

2.3 |

2.4 |

Accounting for Interest In discussing the full effect of any tax or spending proposal on the projected surplus, it is necessary to reflect the fact that increased costs will directly reduce the projected surplus, and by doing so, will lead to higher debt – and therefore higher interest costs – than projected by CBO. The table below shows the full cost over the first decade of the basic Bush tax package and the Chairman’s Mark, with and without these resulting interest costs.

|

Republican Leadership Seems Prepared to Breach Budget Resolution Targets

By relying on these various devices to hold down the cost of the tax-cut package, the proposal's framers were able to circumvent much of the fiscal discipline the Congressional budget resolution targets are supposed to impose. Furthermore, Republican Congressional leaders have made clear they intend to pass additional tax cuts, well beyond the tax-cut measures in the Chairman's Mark, and do not consider the budget resolution's tax-cut limit a binding constraint. House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Thomas was quoted last week in the Daily Tax Report as saying he is "operating under no limit whatsoever" when it comes to passing tax-cut bills this year.

Method of Projecting the Cost of Tax Cuts We project the cost of the proposed tax cuts for the second decade by generally assuming that their costs in the second ten years, measured as a share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), are the same as their costs in 2011. That is, we assume that tax cuts will grow at the same pace as the economy after 2011. This is the standard approach for projecting revenues over longer periods of time. CBO uses it when making long-term budget projections. Our methodology includes an exception to this general approach for repeal of the estate tax and for two other more minor provisions. Because these three provisions are not fully effective until 2011, the full revenue loss caused by these provisions does not occur until 2012, outside the scope of the official ten-year cost estimates. To project the cost of these three highly delayed provisions beyond 2011, we estimate their full revenue loss, based on Joint Tax Committee cost estimates for other tax proposals that included similar provisions but with earlier effective dates. In addition, in calculating the total cost of the tax cuts, we take into account the estimated cost of fixing the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) so it does not affect more taxpayers than under current law (i.e., so that the tax cuts under consideration do not cause more taxpayers to become subject to the AMT). We also take into account the cost of permanently extending the Research and Experimentation tax credit, as proposed by the President, and of making permanent two new tax cuts in the Senate Mark that the Mark sunsets after 2005 or 2006. (For additional details, see Calculating and Projecting the Full Cost of Tax Cuts, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, forthcoming.) |

Chairman Thomas' comments have been echoed by other Republican members, including House Chief Deputy Majority Whip Roy Blunt and Senate Majority Whip Don Nickles. The approach appears to be to write tax cuts into minimum-wage legislation, Patients' Bill of Rights legislation, and possibly other popular legislation that is likely to secure the 60 votes needed in the Senate to breach the budget resolution targets. If Congress can ignore the budget resolution targets in this manner, the targets will essentially have become meaningless.

Estate Tax Repeal

The repeal of the estate tax is one of the most costly components of the President's plan, representing over one-quarter of the cost of the Administration's package when all provisions are fully in effect. The Joint Tax Committee estimates that the estate-tax repeal provision in the Grassley-Baucus plan costs only $145 billion over ten years, less than half the $306 billion cost the Joint Committee has assigned to the President's proposal. Although the Chairman's Mark increases the amount of an individual's estate that is exempt from taxation from the current level of $675,000 to $4 million by 2010, the measure relies on three tactics to hold down the costs of its estate-tax provision over the ten years the budget covers.

- The Chairman's Mark reduces estate and gift tax rates far more slowly than the President proposed, with the top rate falling gradually from 55 percent today to 40 percent by 2010.

- The Mark delays repeal of the estate tax until 2011, two years later than the President proposed. Because it takes a year or two to settle an estate, the full costs of repeal would not occur until after 2011, outside the ten-year period the budget resolution covers.

- The Mark repeals the state "death tax credit" in 2005. Under current law, estate taxpayers receive a dollar-for-dollar credit against their federal estate tax liability for state estate and inheritance tax payments, up to a maximum amount. This credit allows states to raise revenue — about $6 billion in 1999 — without increasing the estate-tax payments that heirs must make. Because state estate taxes are generally crafted in ways that specifically tie them to this credit, repeal of the credit will result in states losing most of these revenues. (If these states chose to reenact a separate estate tax in the absence of the federal credit, the overall estate-tax burden on heirs will increase, a factor that will make it very difficult politically for states to avoid these revenue losses.) In other words, one way the Chairman's Mark holds down the cost of its estate-tax reductions over the next ten years is by effectively transferring billions of dollars in estate-tax collections from state treasuries to the Federal Treasury and using these receipts to offset some of the federal revenue losses that would result from the proposed estate-tax cuts.

While these mechanisms hold down the costs of the estate-tax provisions in the period before repeal would occur, they have no impact on costs after repeal take place — that is, in the period after 2011. The Joint Tax Committee issued a report earlier this year showing that repeal of the estate and gift tax would result in massive income tax avoidance and attendant large revenue losses. According to the Joint Tax Committee, an additional 80 cents of income tax revenue would be lost for every dollar of estate and gift tax revenue foregone when repeal is fully in effect. As a result, the Joint Committee has estimated that the full cost of repeal would be nearly $100 billion a year by 2011. This income tax avoidance would occur because, in the absence of the estate and gift tax, people will have complete freedom to transfer assets to their children or other family members in lower tax brackets so that income generated by these assets is subject to lower income-tax rates.

The Chairman's Mark proposes to address this problem by repealing the estate tax but retaining the gift tax. Because the estate tax would not be repealed until 2011, the Joint Tax Committee estimate provides no indication of the degree to which the Joint Tax Committee believes this approach will be effective in reducing or eliminating income tax avoidance associated with estate and gift tax repeal. Even if this proposal would reduce income-tax avoidance substantially, there are serious questions as to whether retaining the gift tax in the absence of an estate tax can be sustained politically.

Under current law, the two taxes are coordinated. The $675,000 unified estate-and-gift-tax exemption is applicable to large gifts (over $10,000) made during a person's lifetime. Gift taxes paid during a person's lifetime reduce the amount of estate tax that ultimately must be paid. There thus are few tax consequences if a person chooses to give a gift during his or her lifetime rather than making a bequest after he or she dies. This parity would change if the estate tax were repealed but the gift tax were retained. This situation is likely to engender complaints that the policy makes no sense; some significant number of wealthy people will want to give gifts during their lifetime to their children and will view the gift tax as discriminatory with respect to their desire to give these gifts.

For example, the owner of a family business may have a reason to transfer control of the business to his children before he or she dies. Parents with a disabled child may want transfer assets to the child to assure that the child is provided for as the parents grew older. As a result, there are likely to be strong calls to repeal the gift tax as well, once the estate tax is fully repealed. (Note that the estimates in this paper of the costs in the 2012-2021 period assume the gift tax will be effective in eliminating income tax avoidance related to repeal of the estate tax and that the gift tax can be sustained politically in the absence of the estate tax. If neither of these conservative assumptions is borne out, the cost of the tax cuts in the Chairman's Mark in the second ten years would be higher than the estimates discussed here.)

The Chairman's Mark also would change the treatment of capital gains for inherited assets. This provision would not take effect until the estate tax is repealed, so its impact is not captured in the ten-year cost estimate. It is unclear how much revenue this provision would generate. Earlier Joint Tax Committee estimates implied that a carry-over basis provision would replace less than 13 percent of all estate tax revenues. But that estimate assumed no exemptions from the carry-over basis provision, while the Chairman's Mark provides substantial exemptions that would reduce the revenue the provision would produce. (2) Furthermore, experience from the 1976 tax reform, when carry-over basis was enacted and later repealed, indicates that the complexities of implementing carry-over basis may prove to be insurmountable, leading once again to its repeal before it ever takes effect. Overall, the effectiveness of the carry-over basis provision as a means of offsetting some of the revenue losses associated with estate tax repeal is highly questionable.

Alternative Minimum Tax

The AMT plays a substantial role in lowering the overall cost of the Chairman's Mark by cancelling out some of the tax cuts that otherwise would be provided. The apparent reduction in cost is an illusion, however, as Congress will be compelled to enact AMT reforms in the near future to prevent millions of middle-class taxpayers from paying higher taxes and being subject to much greater tax complexity.

The AMT requires a set of calculations that are separate and distinct from

regular income tax calculations. Taxpayers are required to pay the higher of their regular

income tax or their AMT liability. The reductions in income tax rates in the Chairman's

Mark would lower regular income taxes substantially and thereby greatly increase the

number of taxpayers whose AMT liability (in the absence of reductions in the alternative

tax) will be higher than their regular income tax liability. To address this problem, the

mark raises the AMT exemption by $2,000 for individuals and $4,000 for married couples.

But these increases in the AMT exemption are only temporary; this provision would end

after 2006, and then the AMT exemption would return to the increasingly inadequate

current-law levels. As a result, under the Chairman's Mark, the number of taxpayers

subject to the AMT would skyrocket to 39.6 million by 2011, according to the Joint Tax

Committee.

The AMT requires a set of calculations that are separate and distinct from

regular income tax calculations. Taxpayers are required to pay the higher of their regular

income tax or their AMT liability. The reductions in income tax rates in the Chairman's

Mark would lower regular income taxes substantially and thereby greatly increase the

number of taxpayers whose AMT liability (in the absence of reductions in the alternative

tax) will be higher than their regular income tax liability. To address this problem, the

mark raises the AMT exemption by $2,000 for individuals and $4,000 for married couples.

But these increases in the AMT exemption are only temporary; this provision would end

after 2006, and then the AMT exemption would return to the increasingly inadequate

current-law levels. As a result, under the Chairman's Mark, the number of taxpayers

subject to the AMT would skyrocket to 39.6 million by 2011, according to the Joint Tax

Committee.

This significantly reduces the cost of the tax cuts in the Chairman's Mark, because the AMT would cancel some or all of the tax cuts for the nearly 40 million taxpayers who would be subject to the AMT in 2011. For example, the Joint Tax Committee has estimated that the reductions in income tax rates included in H.R. 3 would cost $292 billion less over ten years because of the impact of the AMT, with 85 percent of these lower costs occurring after 2006. H.R. 3 would result in a total of 35.7 million taxpayers being affected by the AMT in 2011 — 3.9 million fewer than would ultimately be affected under the Chairman's Mark. (In the early years, fewer people would be affected by the AMT under the Chairman's Mark than under H.R. 3.) The cost of the mark is likely to be understated by a substantial amount because of the impact of the AMT, although the Joint Tax Committee has not yet provided a estimate of this cost.

The Treasury Department estimates that under current law, more than half of all taxpayers who are affected by the AMT by the end of the decade will have incomes below $100,000, with more than two million of them having incomes below $50,000. (3) These problems would be aggravated by the proposals in the Chairman's Mark; according to the Joint Tax Committee, these proposals would nearly double the number of taxpayers hit by the AMT by 2011, as compared to current law. This growth in the AMT is neither in keeping with its original policy intent nor politically sustainable. As a result, virtually all knowledgeable observers believe Congress will take action to reform the AMT in the next few years. When that action is taken, the cost of the tax cuts in the Chairman's Mark will rise significantly.

End notes

1. In this analysis, references to the "basic Bush tax cut" cover the package proposed by President Bush during the campaign and referred to by the Administration as the "Agenda for Tax Relief" (costing $1.6 trillion over ten years according to the Joint Committee on Taxation). The "Agenda for Tax Relief" does not include the additional $137 billion in health tax credits and other miscellaneous revenue proposals that the President's budget lists separately.

2. The Chairman's Mark would allow the basis of inherited assets to be increased by $1.3 million. Assets bequeathed to a surviving spouse would receive an additional $3 million increase in basis, for a total of $4.3 million. Married couples could combine these exemptions to avoid capital gains taxation on $5.6 million of asset appreciation. For more details on carry-over basis, see Iris Lav and Joel Friedman, "Can Capital Gains Carry-Over Basis Replace the Estate Tax?," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 15, 2001.

3. Robert Rebelein and Jerry Tempalski, "Who Pays the AMT?," Office of Tax Analysis, U.S. Treasury Department, OTA Paper 87, June 2000. The key design flaw is that the AMT exemptions and thresholds are not indexed for inflation. The parameters for the regular income tax, on the other hand, are indexed for inflation. Thus, inflation has the effect of increasing AMT liability over time relative to regular income tax liability.