COST OF TAX CUT WOULD MORE THAN DOUBLE TO $5

TRILLION

IN SECOND TEN YEARS

Tax Cut Would Worsen Deteriorating Long-Term

Budget Forecast

by Richard Kogan, Joel Friedman, and Robert Greenstein

| View PDF full report View PDF short version View HTML short version If you cannot access the file through the link, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

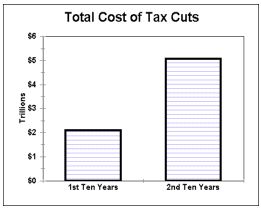

The Administration's tax cuts, in the form the House of Representatives is passing them, would more than double in cost in the second ten years they are in effect, totaling approximately $5 trillion for the 2012-2021 period. Because the House Ways and Means Committee has "backloaded" the cost of some key tax-cut provisions, deferring their cost until near or after the end of the initial ten-year period, the cost in the second ten years provides a better picture of the dimensions of the tax cuts when they are fully in effect. (The $5 trillion figure could be reduced by several hundred billion dollars if measures can be designed, enacted, and enforced to rein in the substantial income tax avoidance the Joint Tax Committee has concluded will occur as a result of repeal of the estate and gift tax.)

The high cost for the

second ten-year period is of particular concern because that is when the costs associated

with the retirement of the baby boom generation are increasingly felt. Furthermore, the

Comptroller General of the United States (who heads the General Accounting Office)

testified last month that "although the 10-year horizon looks better in CBO's January

31 projections than it did in July 2000, the long-term fiscal outlook looks worse"

(emphasis added). The Comptroller General reported the GAO now projects that if the Social

Security surplus is saved in its entirety, with the rest of the surplus used for tax cuts

or spending increases, the total budget will slide back into deficit in 2019. Deficits

will rise rapidly in years after that and eventually reach levels dangerous for the

economy.(1) The Bush tax cuts could exacerbate the already

deteriorating prospect of long-term deficits.

The high cost for the

second ten-year period is of particular concern because that is when the costs associated

with the retirement of the baby boom generation are increasingly felt. Furthermore, the

Comptroller General of the United States (who heads the General Accounting Office)

testified last month that "although the 10-year horizon looks better in CBO's January

31 projections than it did in July 2000, the long-term fiscal outlook looks worse"

(emphasis added). The Comptroller General reported the GAO now projects that if the Social

Security surplus is saved in its entirety, with the rest of the surplus used for tax cuts

or spending increases, the total budget will slide back into deficit in 2019. Deficits

will rise rapidly in years after that and eventually reach levels dangerous for the

economy.(1) The Bush tax cuts could exacerbate the already

deteriorating prospect of long-term deficits.

Despite action by the House to accelerate modestly the implementation of a few portions of the Bush plan, the tax cuts as a whole would phase in slowly. Under the two tax bills the full House has passed and a third bill the Ways and Means Committee approved March 29, few of the tax cut provisions would be fully in effect before 2006. The principal provision that is focused on married couples — a provision that accounts for 80 percent of the cost of all of the marriage provisions when they are fully in effect — would not start to phase in until 2004 and not take full effect until 2009. Furthermore, the estate tax repeal bill is so backloaded that its full cost would not show up until after the ten-year budget period is over. Under the estate tax bill that the House Ways and Means Committee recently approved, the estate tax would not be repealed until 2011; since the tax on an estate usually is not paid until a year or two after the decedent has died, the full revenue loss from estate tax repeal would not be felt until years after 2011.

Congressional Action to Date

Congressional action to date has increased the cost of certain tax cuts beyond what the President's budget shows. For example, the House of Representatives has taken a different and considerably more costly approach to tax relief for married couples than the President's proposal does. In addition, the Joint Tax Committee has estimated that other tax cuts will cost more than the Administration's budget assumes for identical proposals. For example, the Joint Tax Committee estimates the tax rate reductions in H.R. 3 will cost nearly $60 billion more over ten years than the President's budget indicates. To accommodate these two sources of higher costs, the House has phased in some of the provisions very slowly.

Indeed, with each bill the House has taken up, lawmakers have found it more difficult to squeeze the overall tax package into the supposed constraint of $1.6 trillion in revenue losses over the next ten years. The bill to repeal the estate tax is a prime example. The Joint Tax Committee has estimated that if a measure broadly similar to the estate tax legislation the Ways and Means Committee recently approved were made fully effective immediately, the cost would be $662 billion over the next ten years. Yet the Ways and Means Committee bill is estimated to cost $186 billion over this period. The Ways and Means Committee lowered the initial ten-year cost by more than 70 percent by phasing in the bill's provisions extremely slowly. The bill's cost would jump from zero in 2002 and $13 billion in 2006 to $34 billion in 2010 and $49 billion in 2011, which is still well below the full cost. In other words, the cost would nearly triple between the fifth and ninth years, jump another 50 percent between the ninth and tenth years, and continue growing after the tenth year. The cost in the second ten years, from 2012 to 2021, would be approximately $1.3 trillion, dwarfing its cost in the first ten years. (The cost for the second ten years might be reduced, and fall in the $800 billion to $1.3 trillion range, if it proves possible to fashion, enact, and enforce effective strategies to curb the extensive income tax avoidance that estate and gift tax repeal will facilitate; see the box below.)

The cost of the Bush plan, as modified by the two tax bills the House has passed (H.R. 3 and H.R. 6) and the estate tax repeal proposal the Ways and Means Committee has approved (H.R. 8), is $1.8 trillion between 2002 and 2011 (not counting more than $400 billion in increased interest payments on the debt that would have to be made as a result of these tax cuts). This $1.8 trillion figure reflects the cost of the three House bills, as estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation, plus the cost shown in the Administration's budget for the remaining components of its tax package. Adding the Joint Tax Committee's estimate of the cost of modifying the Alternative Minimum Tax to prevent 15 million additional taxpayers from becoming subject to the AMT because of the Bush plan — a cost most observers agree will eventually be incurred — brings the ten-year cost to $2.1 trillion, not counting interest payments.

Over the following ten years, 2012 to 2021, the cost of the Bush plan would be $5 trillion — more than twice its $2.1 trillion cost in the first ten years — again before counting interest costs. All of the tax cuts would be fully in effect in the second ten years. This estimate for the second ten years generally assumes that once a tax cut is fully in effect, its cost will remain constant as a share of the economy. This is a standard assumption in projecting long-term revenue costs. (See the box below for a further discussion of the derivation of the cost estimate for the second ten years.)

If the effects of inflation are removed and all costs are expressed in constant 2001 dollars, the cost in the first ten years would be $1.8 trillion, including the AMT costs. The constant-dollar cost for the second ten years is $3.7 trillion. The cost doubles in the second ten years even after the effects of inflation are removed. Again, these figures do not include interest costs.

The mushrooming cost of the tax cuts in the second ten years is particularly significant in light of the deteriorating long-term budget forecast. The tax-cut debate has focused on projected surpluses, which in recent years have grown larger with each new set of projections. Yet the debate has essentially ignored the long-term forecast (i.e., the forecast for the years outside the 10-year budget window), which has worsened in recent projections due to adoption of a higher estimate of the rate of growth in health care costs over the long term. The estimates that the Medicare Trustees released March 19 on the long-term financial status of Medicare are the latest in a series of recent projections that show long-term health care costs growing faster than had previously been assumed. This change for the worse in the long-term projections suggests that the room available for permanent tax cuts or spending increases has gotten smaller, not larger, as compared with previous budget projections. The combination of these two developments — the worsening of the long-term budget forecasts and the emergence of the Bush tax cuts in a form in which their costs mushroom in the second ten years — is deeply troubling for the nation's long-term fiscal outlook.

Methodology for the 2012 through 2021 Projections Once a tax cut goes fully into effect, the revenue loss it causes generally remains constant as a share of the economy (i.e., as a share of the gross domestic product or GDP). The official Joint Tax Committee cost estimates cover years through 2011. To project the revenue loss from tax cuts in the period from 2012 to 2021, we assumed the revenue losses the Joint Tax Committee estimates in 2011 will hold steady in succeeding years as a share of the economy. The one exception to this rule is the methodology used here for the estate tax. Unlike the income tax code, the parameters of which are indexed for inflation, the current exemption for the estate tax is not indexed for inflation. Under current law, the exemption is scheduled to rise from $675,000 in 2001 to $1 million in 2006 and remain at that level thereafter. As a result, the Joint Tax Committee projects that under current law, estate tax revenues will grow modestly as a share of GDP after 2007. Our estimates assume continuation of this trend (i.e., our estimates assume that under current law, estate tax revenues will continue to grow after 2011 at the same rate as the Joint Tax Committee projects they will grow from 2007 to 2011; the estate tax revenues that would be lost as a result of estate tax repeal thus are assumed to grow at this same rate in the decade after 2011). Joint Tax Committee estimates show that in addition to lost estate tax revenues, repeal of the estate tax also would result in lower income tax revenues. The Joint Tax Committee has estimated that immediate repeal of the estate and gift tax, coupled with use of "carry-over" basis for the valuation of inherited assets for capital gains purposes (a change that saves money), would cost $662 billion between 2002 and 2011 and $97 billion in 2011 alone. The Joint Committee also projects that under current law, estate and gift tax revenue collections will total $410 billion over the same period. The $252 billion difference essentially reflects income tax revenues that would be lost as a result of tax avoidance strategies made possible by estate and gift tax repeal. The Joint Tax Committee estimate shows these lost income tax revenues would rise as a share of GDP throughout the 2002 - 2011 period. To be conservative in making estimates for the second ten years, we assume these lost income tax revenues would stop rising and remain constant as a share of GDP after 2011. Thus, the lost income tax receipts associated with estate tax repeal are treated similarly to other revenue losses in the Bush plan, by being assumed to remain constant as a share of GDP between 2012 and 2021. Only the lost estate tax revenues are assumed to increase modestly during the second decade as a share of GDP. The Joint Tax Committee has indicated that the large income tax losses associated with estate tax repeal might be reduced if provisions could be designed and enacted to deter tax avoidance. Expert testimony before the Ways and Means Committee has raised questions, however, about whether sufficiently stringent measures could be fashioned that would be politically feasible. The estate tax repeal legislation that the House Ways and Means Committee approved March 29 contains only modest measures to address this problem. It directs the Treasury Department to study this matter and develop further recommendations to curb the tax avoidance. The $1.3 trillion figure cited here as the cost of the House estate tax repeal bill in the second ten years reflects the modest anti-tax-avoidance provisions the Ways and Means bill contains and is consistent with the Joint Tax Committee’s estimate of the cost over the first ten years of repealing the estate tax immediately and coupling it with carry-over basis for inherited assets. If additional measures to curb tax avoidance can be designed, enacted, and enforced and prove so effective that they eliminate most of the income tax avoidance that otherwise would occur, the cost could be reduced down toward $800 billion. Whether this can be accomplished is far from clear. |

The Long-Term Picture Is Gloomier Because Projected Health Costs Grow Faster

One argument advanced on behalf of very large tax cuts — or of large spending increases, for that matter — is that budget projections by CBO and OMB now show greater ten-year surpluses than they did as recently as last summer. Implicit here is the notion that those projected surpluses are available indefinitely and therefore can support permanent, large tax cuts or spending increases.

But the projected surpluses do not continue in perpetuity. CBO, GAO, OMB, and outside analysts unanimously agree that, even without a tax cut, those surpluses will turn to deficits once the baby boomers have retired, and that unless Congress ultimately takes action to raise taxes or cut spending, those deficits will eventually become too large for the budget or economy to handle.

In addition, and perhaps most unsettling, while budget projections for the next decade are now more optimistic than they were last year, projections for the long term are now gloomier. The reason is the emergence of a new consensus that the long-term costs of health care will grow far more rapidly than previously assumed.

Reflecting the Cost of Addressing Problems in the AMT As is well known, flaws in the design of the Alternative Minimum Tax will result in a very large increase under current law in the number of taxpayers who will become subject to the AMT in the years ahead. The Bush tax plan, as modified by the House, compounds these problems. According to the Joint Tax Committee, the plan would cause 15 million additional taxpayers to be subject to the AMT. The Joint Tax Committee estimates that the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT will grow from 1.5 million in 2001 to 20.7 million in 2011 under current law. The Bush tax proposals, particularly the rate reductions that apply to the upper brackets, would raise the number of taxpayers who would be subject to the AMT to 35.7 million by 2011. The Joint Tax Committee also estimates that it will cost $292 billion over ten years to modify the AMT so the Bush tax cut does not cause the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT to rise beyond the number that would be affected under current law. Most observers concur this step is virtually certain to be taken (and, in fact, that Congress will likely go further, at additional cost, and also take steps to prevent the large growth in the AMT that otherwise would occur under current law). Whether Congress acts this year to address the AMT problem or defers action for a year or two will not alter the fact that the Bush plan adds about $300 billion over ten years to the cost of fixing the AMT problem or the reality that the cost of AMT adjustments will almost certainly be borne over the next ten years. (The tax bill the House passed March 29 includes certain small adjustments to the AMT, but these provisions will not have a significant effect on the cost of addressing the AMT’s rather daunting problems.) |

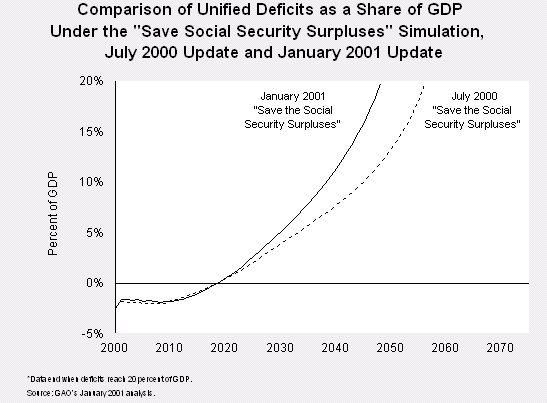

Why Does the Long-Term Picture Look Worse? The graph below, taken from recent testimony by the Comptroller General (the head of the General Accounting Office), illustrates the dimensions of our long term fiscal problems by showing how quickly the baby boomers’ retirement is projected to drive the federal deficit to unsustainable heights. Note that the latest estimates show a more rapid explosion of deficits — and therefore a greater fiscal gap — than the estimates made just six months earlier. In his recent testimony, the Comptroller General explained the problem: "Although the 10-year horizon looks better in CBO’s January 31 projections than it did in July 2000, the long-term fiscal outlook looks worse. ... This worsening is largely due to a change in the assumptions about health care costs over the long term. In recent months there has been an emerging consensus that the long-term cost growth assumption traditionally used in projecting Medicare and Medicaid costs in the out-years is too low. A technical panel advising the Medicare Trustees stated this conclusion in its final report ... the panel recommended that in the last 50 years of the 75-year projection period, per-beneficiary program costs should be assumed to grow at a rate one-percentage point above per-capita GDP growth. CBO made a similar change to its Medicare and Medicaid long-term cost growth assumptions [in] its October 2000 report..."

|

- CBO updated its various measures of the long-term deficit last fall. Since numbers expressed over 75 years are often hard to comprehend, CBO expresses the size of future deficits by showing how large they are in today's terms. In its recent update of the long-term budget situation, CBO reported that as a result of the new estimates of health care cost growth, it now projects future deficits to be between $31 billion and $114 billion per year greater in today's dollars than it had previously thought. In a similar vein, estimates by economists William Gale of the Brookings Institution and Alan Auerbach of the University of California atBerkeley find that the long-term fiscal gap has grown by more than $100 billion a year in today's dollars.(2)

Similarly, in their new report on Medicare's financial status, issued March 19, the Medicare Trustees substantially increased their estimate of the size of the long-term financing deficit in the Medicare Hospital Insurance program. The Trustees now project a long-term financing hole that is more than 60 percent bigger than the shortfall they projected a year ago. The Trustees explained that "the most significant change ... is that health care costs per capita are assumed to increase at a faster rate than had been assumed in previous reports. ... [This] has the effect of substantially raising the long-term cost estimates for both the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) and Supplemental Medical insurance (SMI) programs and in our judgment represents a more realistic assessment of likely long-term cost growth."(3)

Conclusion

Long-term projections of the budget show a return of deficits that eventually climb to levels that will not be sustainable for the economy. Very large tax cuts or spending increases enacted now will aggravate these problems and make it still harder to maintain sound budgets in the future. The long-term picture is now acknowledged to be worse, rather than better, than previously thought; estimates of the size of long-term deficits have grown substantially over the past year. One can reasonably conclude that the room available for permanent tax cuts or spending increases has shrunk, not expanded, as compared with previous projections.

The Worsening Medicare Financing Picture The Social Security and Medicare Hospital Insurance actuaries use a concept very similar to the "fiscal gap" to measure the long-term solvency of those trust funds. They calculate the amount of the immediate, permanent increase in the payroll tax that would be needed to keep each trust fund solvent for 75 years. The new Trustees’ report places the size of the long-term "fiscal gap" for Medicare Hospital Insurance at 1.97 percent of taxable payroll over 75 years. This represents a 62 percent increase over the 1.21 percent-of-payroll gap the Trustees estimated in last year’s report. All of this deterioration is due to the more somber view of the long-term growth of per-person health care costs. |

This deterioration in the long-term picture raises the question of how the nation can ultimately afford a tax cut whose cost would likely reach $5 trillion over the second ten-year period, when the tax cut is phased in fully. A tax cut of this dimension is likely to result in a significant degree of future budgetary distress.

End notes

1. Long-Term Budget Issues: Moving from Balancing the Budget to Balancing Fiscal Risk, Testimony of Comptroller General David M. Walker before the Senate Budget Committee, February 6, 2001.

2. CBO, The Long-Term Budget Outlook, October 2000, and The Long-Term Budget Outlook: An Update, December 1999. CBO and other analysts who look at budget issues over very long periods of time use a concept called the "fiscal gap" to express the size of future deficits. The fiscal gap is the size of the permanent spending cut or tax increase that would need to be enacted this year to limit future deficits to a manageable size. Fiscal gaps are expressed as a share of the economy, i.e. as a percentage of GDP. For instance, if CBO shows a fiscal gap of 2.0 percent of GDP, CBO is saying that an immediate and permanent tax increase (or spending cut) of $206 billion for 2001, and growing with the economy each year thereafter, will suffice to keep future deficits under control for the next 75 years. ("Keeping future deficits under control" means that, at the end of 75 years, the federal debt will be the same share of the economy it is now, about 31 percent). Between the fall of 1999 and the fall of 2000, CBO increased one measure of the fiscal gap by 0.3 percent of GDP, a second measure by 1.0 percent of GDP, and a third by 1.1 percent of GDP. Alan Auerbach (University of California at Berkeley) and William Gale (Brookings Institution) found that their estimates of the 70-year fiscal gap increased by between 1.2 percent of GDP and 1.3 percent of GDP. Tax Cuts and the Budget, Tax Notes, March 26, 2001.

3. Status of the Social Security and Medicare Programs, A Summary of the 2001 Annual Reports. Mar. 19, 2001.