Shift In Costs From Medicare To Medicaid Is A Principal Reason

For Rising State Medicaid Expenditures

by

Leighton Ku

| PDF of this report |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

State budget crises have drawn attention to double-digit increases in state Medicaid expenditures. A key reason for rising Medicaid expenditures is that gaps in federal Medicare coverage for seniors and people with disabilities have resulted in a substantial shift in costs in recent years from Medicare to Medicaid. This cost shift has forced state Medicaid programs to bear a larger share of the health care costs of the millions of low-income elderly and disabled people enrolled in both programs. In short, structural deficiencies in Medicare are a chief force driving Medicaid expenditures upward.

Medicare — the federal insurance program for seniors and people with disabilities — and Medicaid — the joint federal-state insurance program for low-income people — share the health insurance costs of low-income seniors and people with disabilities. Almost all elderly Medicaid beneficiaries and about two-fifths of disabled Medicaid beneficiaries are enrolled in Medicare. Individuals who participate in both Medicaid and Medicare are referred to as “dual eligibles.”

For low-income individuals fully enrolled in both programs, Medicaid pays for services that Medicare does not cover — like prescription drugs and long-term care — and also covers the deductibles, coinsurance and premiums that Medicare assesses beneficiaries. In addition, state Medicaid programs provide partial coverage for Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below 120 percent of the poverty line ($10,780 in annual income for a single person and $14,540 for a couple).

Some key facts:

- Some 35 percent of all Medicaid expenditures are on behalf of “dual eligibles,” i.e., on behalf of beneficiaries also enrolled in Medicare.

- About three-quarters of the total projected growth in Medicaid expenditures is attributable to rising costs of care for the aged and disabled, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

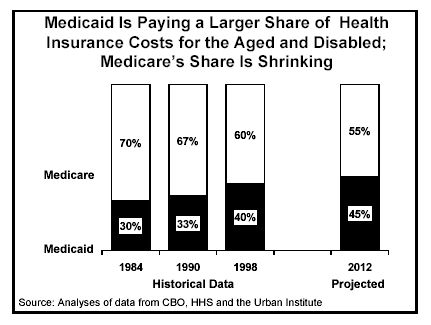

- Medicaid has been financing a growing share of health insurance costs for the aged and disabled. In 1984, Medicaid paid for 30 percent of the total public expenditures for health insurance for the aged and disabled and Medicare paid for 70 percent. By 1998, Medicaid was covering 40 percent of the public health insurance costs of the aged and disabled, with Medicare’s share having fallen to 60 percent. By 2012, Medicaid’s share is projected to rise to 45 percent, while Medicare’s share will drop to 55 percent.

- If Medicaid expenditure growth for seniors could be brought down to the levels projected for Medicare, cumulative state expenditures for Medicaid would be $47 billion lower over the period 2003 to 2012. If Medicaid growth rates for people with disabilities could be brought down to Medicare levels, states’ savings would be even larger.

The shift in costs from Medicare to Medicaid has primarily been caused by structural deficiencies in Medicare coverage, which has failed to keep pace with the medical and demographic needs of seniors and people with disabilities:

- Medicare does not cover outpatient prescription drugs, so Medicaid must cover all prescription drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries fully enrolled in both programs. The cost of prescription drugs is the fastest growing segment of health care spending. More than half of all Medicaid expenditures for prescription drugs are incurred for dual eligibles.

- Changing medical practices have lowered the length of time that people are hospitalized and increased the use of prescription drugs and ambulatory care. While these medical advances can reduce overall health care costs and improve quality of care, they have the paradoxical effect of increasing Medicaid expenditures while lowering Medicare costs. Reducing hospital expenditures for dual eligibles saves substantial sums for Medicare — which is the “primary payer” for hospital expenses — but not for Medicaid. And additional expenses for prescription drugs are borne entirely by Medicaid. (See box on next page)

- Furthermore, Medicaid covers long-term care, while Medicare does not. A majority of the Medicaid expenditures for seniors and people with disabilities are for long-term care services, such as nursing home or home health care services. As the baby boomers age and retire, Medicaid’s long-term care costs will grow heavier.

Legislative changes in Medicare that Congress may consider this year could have a large effect on the long-term sustainability of state Medicaid programs. Federal policies could help restore the balance in federal-state responsibilities by providing federal financing for prescription drugs provided to dual eligibles or by having the federal government assume a larger share of the costs for dual eligibles. Conversely, legislative changes that increase cost-sharing in Medicare could make state Medicaid costs rise even higher, since Medicaid pays the cost-sharing obligations of most dual eligibles.

|

An Example of How New

Medical Practices that Lower Medicare Costs Consider a simplified example for a person dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare. Imagine that a new approach to treating this patient’s illness reduces the costs of treatment from $22,000 ($15,900 in hospital costs, $4,100 in physician payments and $2,000 in outpatient drug costs) to $17,000 ($5,900 hospital costs, $6,100 in physician payments and $5,000 in drugs). From an overall perspective, the new treatment approach saves $5,000. Under the old way of treating the disease, Medicaid’s share would be $3,740 ($2,000 for the prescription drugs, $840 for the hospital deductible, $100 for the physician deductible and $800 for the 20 percent coinsurance for physician services). Medicare would pay the rest, $18,260. With the new approach, Medicaid would pay about $7,140 ($5,000 for prescription drugs, $840 for the hospital deductible, $100 for the physician deductible and $1,200 for the physician coinsurance). The Medicare expenditure would be about $9,860. Using the new approach instead of the older one lowers Medicare expenditures by $8,400, but increases Medicaid expenditures by $3,400. Even though the new approach reduces overall health care expenses, Medicaid spends more. Because Medicare has a fixed deductible for all inpatient care (during the first 60 days) and Medicaid pays the deductible for dual eligibles, the Medicaid portion of the bill is not lowered by reductions in inpatient costs, and Medicaid must cover the full increased costs of prescription drugs and also pay for a portion of the increased physician costs. Even if the increase in prescription drug costs is set aside, it is clear that Medicaid does not share in the savings that Medicare obtains through lower inpatient hospital costs. |

Legislative changes that cap the federal Medicaid payments that are made to states on behalf of some or all Medicaid beneficiaries also could adversely affect states. Such proposals would force states to bear 100 percent of Medicaid costs above the cap for those beneficiaries whose health care coverage costs are subject to the cap. With the retirement of the baby-boom generation fast approaching and Medicaid expenditures for the elderly and disabled poised to grow substantially as a result, a cap on the federal share of such expenditures could eventually result in further cost shifts to states.

Finally, even if Congress adopts helpful Medicare policies this year that ease Medicaid costs in areas such as prescription drugs, such policies will probably require at least several years to phase in. Such changes consequently would fail to address the immediate budget crises that states confront. Proposals to provide federal fiscal relief to states on a temporary basis would serve as an effective short-term complement to longer-term reforms that help restore the traditional state-federal balance in financing health care for low-income seniors and people with disabilities.