|

February 14, 2007

THE ADMINISTRATION AGAIN PROPOSES TO SHIFT

FEDERAL MEDICAID COSTS TO STATES

By Leighton Ku, Andy Schneider, and Judy Solomon

In its new budget, the Administration proposes cuts in federal Medicaid funding that total $24.7 billion over the next five years and $60.9 billion over ten years through a combination of legislative changes and regulatory action.[1] These reductions are more than five times as large over the next five years as the federal Medicaid cuts enacted by the Congress last year in the Deficit Reduction Act and would deepen the cuts in health assistance for low-income people.[2]

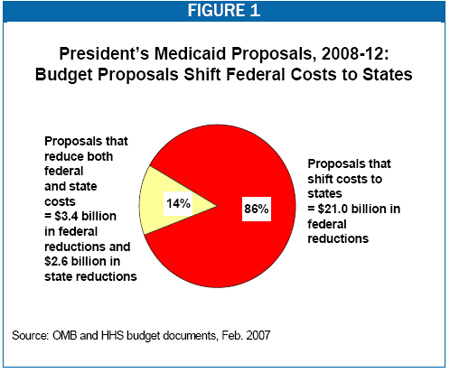

About six out of every seven dollars’ worth of savings proposed in the Administration’s new budget would reduce federal Medicaid spending by shifting costs directly from the federal government to the states, as seen in Figure 1. (The Administration also proposed a large Medicaid cost shift to states in its FY 2007 budget.[3]) For example, the new budget proposes to reduce the federal matching rate for the costs of certain administrative activities, such as inspecting nursing homes for quality and safety. The costs of inspecting nursing homes would not disappear, but the state’s share of the cost would increase. These Medicaid cost shifts are in addition to other proposals in the President’s budget that would reduce other grants in aid to states.[4] The Administration’s budget also contains a number of federal tax proposals that could result in the loss of significant amounts of state revenue, further compounding the fiscal squeeze on the states.[5]

If enacted, the Administration’s Medicaid proposals would substantially reduce the federal funds that states use to purchase covered services and administer their programs. States — many of which have already taken aggressive measures to reduce Medicaid cost growth[6] — would have three options for making up the loss of federal Medicaid funds: cutting back on their Medicaid programs by reducing eligibility, benefits, or payments to providers; cutting back on other state programs and using those funds to replace federal Medicaid dollars lost; or increasing taxes. In states that opt to cut back on their Medicaid programs, low-income families, individuals with disabilities, and seniors would be at risk for disenrollment, increased out-of-pocket costs, or restricted access to providers. In states that opt not to cut back on their Medicaid programs but choose instead to replace the lost federal dollars with state funds, fewer state funds will be available to pay for coverage expansions among uninsured children and adults, such as that underway in Massachusetts.

How Would the Administration’s Proposals Reduce Federal Medicaid Spending by $24.7 Billion Over Five Years?

Medicaid is administered and financed jointly by the federal government and the states, with the federal government matching from 50 percent to 76 percent (depending on the state) of the costs that states incur in purchasing health and long-term care services for eligible low-income people. Under this federal-state matching arrangement, there are two ways that the federal government can reduce its Medicaid spending. It can achieve efficiencies in the purchasing of needed services for Medicaid beneficiaries. An example of this approach— which reduces both federal and state costs— would be to increase the rebates that drug manufacturers are required to pay Medicaid for the prescriptions that Medicaid covers. This would lower the net price of these prescriptions to the program, resulting in savings for both the federal and state governments. In the alternative, the federal government could also reduce its spending by limiting the state Medicaid expenditures that it is willing to match, thereby shifting costs to state budgets, rather than reducing those costs. More than four-fifths of the Administration’s new Medicaid budget-reduction proposals would achieve federal savings by shifting costs directly from the federal government to the states.

The Administration’s budget contains both legislative and regulatory proposals affecting Medicaid. The budget proposes legislative changes that would reduce federal spending by $12 billion over five years, offset somewhat by proposals that would increase federal spending by $1.2 billion over five years. These proposals would require congressional approval. The Administration is also proposing $12.7 billion in regulatory reductions over the next five years. The Administration’s gross legislative and regulatory savings total $24.7 billion over the next five years and $60.9 billion over the next ten years. (A more detailed listing of all the budget proposals and the Administration’s estimates of their budget effects is presented in Table 1 on the last page.)

What Legislative Reductions Does the Administration’s Medicaid Budget Propose?

The new budget proposes ten legislative changes that would reduce federal Medicaid spending. (This analysis discusses only those legislative proposals that have a budgetary impact.) Three of the proposed changes, which account for $8.2 billion in reduced federal spending (or more than two-thirds of the total legislative savings), represent cost shifts to states. Versions of all three proposals have been unsuccessfully advanced in previous budgets.

- The Administration’s budget would reduce the federal matching rate for all administrative costs to 50 percent. This proposal would produce estimated federal savings of $5.3 billion over five years, making it the single largest Medicaid reduction in the Administration’s budget.[7]

Currently, most state administrative costs are matched at 50 percent; the costs of some high-priority administrative activities, however, are matched at higher rates. States receive federal funds at a 75 percent matching rate for operating a Medicaid management information system. for inspecting nursing homes to ensure quality of care and the safety of nursing home residents, for contracting with independent review organizations to monitor the quality and need for services received by beneficiaries. and for investigating and prosecuting fraud and abuse in Medicaid.[8]

Under the Administration’s proposal, all of these enhanced matching rates would drop to 50 percent. The resulting $5.3 billion in federal savings represents a pure cost shift to the states. Not only are these administrative activities mandated by the federal government, they all are essential to the fiscal integrity of state Medicaid programs and to the protection of vulnerable patients served by providers or managed care plans paid by the programs. States will have little choice but to replace the lost federal funds with state funds.

|

Budget Would Reduce Funding for States’ Administrative Costs

Even as States’ Administrative Responsibilities Are Growing |

| Legislative savings proposed in the new budget would reduce federal funding for state administration of Medicaid by a total of $7.1 billion over five years. These cuts would occur during a period when recent federal mandates have increased states’ workloads. These include the requirement that states help administer the low-income subsidies for the Medicare drug benefit, that they document citizenship of most Medicaid applicants and beneficiaries, and that they implement new program integrity initiatives, like the Payment Error Rate Measurement System (PERM). While Medicaid administrative costs are low (5 percent of total costs in 2007) and have been rising modestly (4 percent annual growth since 2004), reductions in federal matching payments will make it more difficult for states to adequately staff and manage their programs. Note: For illustrations of the administrative costs associated with some of the recent federal administrative mandates, see Donna Cohen Ross, “New Medicaid Citizenship Documentation Requirement Is Taking A Toll: States Report Enrollment Is Down And Administrative Costs Are Up,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Feb. 2, 2007, and the American Public Human Services Administration, “PERM Survey: Initial Implementation Information Experiences,” Feb. 2007. |

- The Administration proposes to reduce the federal matching rate for the cost of targeted case management services to a flat 50 percent for every state. (In 38 states and the District of Columbia, the federal Medicaid matching rate exceeds 50 percent in FY 2007.) Targeted case management services help specific groups of Medicaid beneficiaries, such as low-income pregnant women, access health care and other needed services. This proposal would affect all states with federal matching rates above 50 percent that have opted to cover targeted case management services. The federal savings are estimated at $1.2 billion over five years.

- The Administration also would reduce federal Medicaid matching payments to 46 states that have historically pooled the administrative costs of making eligibility determinations for families and children receiving Medicaid, TANF, and food stamps. This proposal, technically known as “cost allocation,” effectively reduces the federal matching rate for state administrative costs related to Medicaid eligibility determinations. The federal savings from this proposal are estimated at $1.8 billion over five years.

The budget contains another legislative proposal that would also reduce federal payments to states, but there is insufficient detail to determine whether this proposal would shift costs to the states. The proposal would require states to report on Medicaid performance measures and “link performance to Federal Medicaid grant awards.” The Administration estimates that the proposal would result in federal savings of $330 million over five years.

The proposal does not specify the purpose or content of the performance measures, and it does not explain how performance would be linked to federal Medicaid matching payments. It is possible that the proposal would pay bonuses to states that are able to reduce their rates of Medicaid spending growth, and that the estimated federal savings of $330 million are net of such bonus payments. It is also possible that the estimated federal savings represent penalties imposed upon poorly performing states in the form of reduced matching payments. In either case, the Administration’s budget does not contemplate that federal Medicaid spending will increase if state performance, however measured, were to improve.

Almost all of the remaining legislative savings proposed by the Administration, $3.4 billion over five years, derive from proposals that would reduce Medicaid spending in such a way that savings would accrue to both the federal and state governments. Based on these estimates of federal savings, we calculate that states may save $2.6 billion from these policies.

- The Administration proposes a number of changes to Medicaid pharmacy policy. It would limit Medicaid payments to pharmacists for multiple source drugs (those with three or more manufacturers) to 150 percent of the “average manufacturer price” of the drug. Under the Deficit Reduction Act, the reimbursement limit for such drugs was set at 250 percent of the average manufacturer price.

The Administration would also allow states “to use private sector management techniques to leverage greater discounts through negotiations with drug manufacturers” in order to create prescription drug formularies. Currently, states may designate certain medications as “preferred” and pay for these medications without further review; for medications not listed as preferred, states pay only if the medication is authorized in advance as being medically necessary. Although details are not available, it is possible that under this Administration proposal, states would be allowed to exclude coverage of non-preferred drugs altogether, so these medications would not available to Medicaid beneficiaries regardless of medical need.

Finally, in order to prevent prescribing fraud, the Administration would require all states in which physicians write prescriptions by hand to use “tamper-resistant” prescription pads. Total federal savings from these three proposals are estimated at $2.3 billion over five years. Corresponding state savings would be about $1.7 billion.

- The new budget includes two proposals relating to Medicaid assets policy. The first has to do with the amount of home equity an individual without a spouse living in the home may have and qualify for Medicaid long-term care services. Under the Deficit Reduction Act, permissible home equity was limited to $500,000; states were allowed to raise this amount to $750,000. The budget proposes to take away this state option, setting a nationwide ceiling at $500,000.

The second proposal concerns assets verification. Currently, the Social Security Administration is operating pilot projects in various locations that use electronic financial records to verify the assets of elderly or disabled applicants for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). The Administration would require states to establish pilots in the same locations to verify the assets of Medicaid applicants. As a result, some elderly or disabled individuals would presumably be denied Medicaid coverage. Total federal savings from these two proposals are estimated at $1.1 billion over five years. Corresponding state savings would be about $830 million.

What Regulatory Reductions Does the Administration’s Medicaid Budget Propose?

- The Administration’s budget proposes to reduce federal Medicaid spending by $12.7 billion over the next five years and $31.4 billion over the next ten years through four regulatory changes, each of which represents a shift of costs from the federal government to the states. Although in the past, the Administration has advanced some of these proposals as legislative initiatives without success, it now appears to believe that it has sufficient statutory authority to take these actions administratively, without Congressional approval.

|

Some Budget Proposals Could Undercut

State Efforts to Cover the Uninsured |

| A growing number of states are considering plans to achieve universal health coverage. Others, such as Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont, are already implementing plans to expand health coverage. Medicaid is an essential part of financing these efforts, through direct coverage of state residents and through federal funds that help subsidize health care for other low-income residents without insurance. The Administration’s budget does not include any new federal Medicaid funds to assist states in expanding coverage. To the contrary, by shifting certain costs from the federal government to the states, the budget would reduce the federal funds available to the states for their current programs, making it harder for states to expand health coverage to reduce the number of low-income residents who are uninsured.

Massachusetts is a case in point. The state’s health reform plan includes an expansion of Medicaid and SCHIP coverage for children, as well as an increase in Medicaid coverage for parents, pregnant women, people with disabilities, and some unemployed adults. Other low-income adults in Massachusetts who are not eligible for Medicaid and do not have access to employer-sponsored coverage will receive subsidized coverage through a new health plan. Massachusetts is relying on federal Medicaid funds to help in paying for these subsidies.

The regulatory and legislative proposals in the Administration’s budget would shift new costs to the states and thereby lower the federal funds available to Massachusetts. Massachusetts would have less money available to finance its health reform plan, making it harder for the state to achieve its goal of universal coverage. |

- The Administration’s budget proposes to limit the amount of Medicaid payments to hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions that are operated by state or local governments to the cost of furnishing services to Medicaid beneficiaries. Under this policy, governmental providers would no longer receive Medicaid reimbursement for the costs of serving uninsured low-income patients. Because public hospitals and nursing homes will continue to serve uninsured patients, they will continue to incur costs in furnishing services to these patients; the federal government, however, would no longer participate in those costs through regular federal Medicaid payments. The Administration had proposed to limit payments to public providers as part of its fiscal year 2005 and 2006 legislative proposals, but Congress did not act on these proposals. Last month, the Administration issued a notice of proposed rulemaking to implement this policy.[9] Savings to the federal government are estimated at $5 billion over five years.

- Currently, Medicaid pays for the cost of covered services for eligible children with disabilities that are part of a child’s special education plan under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). State and local school districts also can be reimbursed by Medicaid for transportation costs. The Administration’s budget proposes to phase out federal reimbursements for some of these administrative and transportation costs. That would reduce federal Medicaid payments to state and local school districts by an estimated $3.6 billion over five years and $9 billion over ten years.

- The Administration’s budget proposes to limit the types of services that states can cover with federal matching funds under the current state Medicaid option to cover rehabilitation services. Under this proposal, states would lose federal matching funds for the costs of certain services for which matching funds are currently allowed, such as special instruction and therapy for Medicaid beneficiaries with mental illness or developmental disabilities. Here, also, there would be no state savings. The federal government would reduce its Medicaid spending by an estimated $2.3 billion over five years and $4.3 billion over ten years by shifting these costs to the states.

- The Administration’s budget proposes to eliminate federal Medicaid payments for the costs of graduate medical education (GME). Teaching hospitals with residency programs employ young physicians to provide inpatient and outpatient services to their patients; GME payments help these facilities recover the costs of these salaries. The residents in these programs are often the direct care providers for Medicaid patients. Under current law, states have the flexibility to include the costs of GME in their Medicaid reimbursement to teaching hospitals.

The Administration budget would end federal matching payments for these costs to produce savings for the federal government of $1.8 billion over five years and $6.2 billion over ten. If the states make up the shortfall, the costs will be shifted to them. If the states do not make up the shortfall, these costs will be shifted to the teaching hospitals, their residents, or their patients.

What Legislative Initiatives Does the Administration’s Medicaid Budget Propose?

The Administration’s Medicaid budget does not contain any regulatory initiatives that would increase federal Medicaid outlays. It does propose three legislative initiatives that would increase federal Medicaid spending by $1.1 billion over five years. The proposals for transitional medical assistance (TMA) and coverage for “Qualified Individuals” would extend coverage through 2008, while the SSI refugee provision would be through 2010.[10] The new budget does not include any new federal Medicaid resources to assist states that seek in expand health care coverage for their low-income populations. The Administration’s “Affordable Choices” initiative for the uninsured involves a diversion of federal funds that currently support public and private safety net hospitals (see box below).

- Under current law, families leaving welfare for work retain Medicaid eligibility for up to 12 months. TMA, which was enacted under President Reagan and provides an essential work support as families leave welfare for employment, is slated to expire on

June 30, 2007. The Administration proposes to extend TMA through September 30, 2008 at a cost to the federal government of $665 million.

- Under current law, states pay the Medicare Part B premiums ($93.50 per month in 2007) for low-income elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below 135 percent of the federal poverty level and low resources. But for beneficiaries with incomes between 120 and 135 percent of the poverty level ($1,021 - $1,123 per month for an individual in 2007), a group known as “Qualified Individuals” or QIs, the federal government matches 100 percent of the cost of these Medicare premium subsidies up to a fixed amount for each state.

This federal funding expires September 30, 2007. At that point, either states would continue the premium subsidies with their own funds, or the beneficiaries would have to pay the premiums themselves (through a deduction from their monthly Social Security checks). The Administration proposes to extend this funding through September 30, 2008, at a cost of $425 million to the federal government.

- Under current law, refugees and asylees who are elderly or disabled are permitted to receive SSI benefits and the Medicaid benefits that flow from SSI eligibility during their first seven years in the United States. After this point, they lose SSI and Medicaid benefits unless they become citizens; the loss of benefits after that time harms thousands of elderly and frail individuals.[11] The Administration is proposing to allow these individuals to remain eligible for SSI for eight years, a change that would be in effect through fiscal year 2010. This proposal would increase federal Medicaid expenditures by an estimated $99 million.

|

The Administration’s “Affordable Choices Initiative”

Would Limit State Flexibility in Expanding Health Coverage |

| The Bush Administration announced a two-part health initiative just before the State of the Union address. The first part is a proposal to change the tax treatment of employer-sponsored health insurance and create a standard deduction for health insurance costs. The second part is an initiative called “Affordable Choices,” which encourages states to take federal funds used to support hospitals and other health care providers that provide care to the uninsured and instead use the funds to pay for “basic private health insurance” for uninsured residents. Even though few details have been released, some shortcomings of “Affordable Choices” are apparent:

- No new funds are provided to expand coverage, even as the Administration’s budget proposals would shift substantial costs to the states. Rather than re-invest these federal savings by providing support for state efforts to expand coverage, the Administration is urging states to expand coverage by taking funds away from health care providers that provide care to the uninsured.

- The funding that currently goes to support uncompensated care delivered by a state’s safety net providers is not sufficient to provide comprehensive coverage to all low-income state residents who cannot afford to purchase health coverage. As a result, health providers would still be called upon to provide uncompensated care to people who are uninsured or underinsured.

- The proposal appears to rest on the assumption that low-income people would be able to use subsidies to purchase affordable coverage in the individual health insurance market. Such an assumption, however, is untested and likely unfounded. Many individuals with chronic conditions would likely be unable to purchase coverage in the individual market.1 The Administration would allow states to use their diverted uncompensated care funds for high risk pools “for very sick individuals who are deemed uninsurable in the non-group market,” but in most states, coverage provided through high risk pools is very costly, provides limited benefits, and entails long waiting periods for coverage of pre-existing conditions.2

1 Karen Pollitz and Richard Sorian, “Ensuring Health Security: Is the Individual Market Ready for Prime Time” Health Affairs, web exclusive, October 2002.

2 Deborah Chollet, “Expanding Individual Health Insurance Coverage: Are High-Risk Pools the Answer?” Health Affairs, web exclusive, October 2002. |

What Do the Administration’s Medicaid Budget Proposals Mean for Beneficiaries?

Federal cost-shifts of the magnitude proposed by the Administration in Medicaid and other federal grant-in-aid programs cannot be addressed by states through greater program efficiencies such as reducing fraud and abuse; the amounts involved are much too large. To make up for the loss of federal Medicaid funds, states would face three basic choices: cutting back on their Medicaid programs, cutting back on other state programs and using those funds to replace federal Medicaid dollars lost, or increasing taxes.

In states that opt to cut back on their Medicaid programs, low-income families, individuals with disabilities, and seniors would be at risk for disenrollment, increased out-of-pocket costs, or restricted access to providers. In states that choose instead to replace the lost federal dollars with state funds, fewer state funds will be available to pay for coverage expansions among uninsured children and adults, such as that underway in Massachusetts.

|

TABLE 1:

President's Fiscal Year 2008 Medicaid Budget Proposals: Federal Outlay Effects |

|

A. Proposals That Lower Medicaid Costs and Reduce Both Federal and State Expenditures |

FY 2008-12 FY 2008-17

(in millions of $) |

Legislative

Reduce payments to pharmacists

Permit more restrictive drug formularies

Require tamper resistant prescription pads

Increase third party liability collections

Restrict home equity asset levels to $500,000

Require Medicaid adoption of SSA asset verification projects

Subtotal A, legislative (no regulatory) |

-$1,200

-870

-210

-85

-430

-640

-3,435

|

$3,250

-2,170

-545

-300

-1,130

-1,755

-9,150 |

|

B. Proposals That Lower Federal Funding to States Without Reducing Medical Costs and Thereby Shift Costs to States* |

|

Legislative

Lower all administrative match rates to 50%

Reduce Funds for administrative expenses (cost allocation)

Lower targeted case management match rate to 50%

Subtotal, legislative |

-$5,315

-1,770

-1,160

-8,245 |

-12,325

3,720

2,910

18,955 |

Regulatory

Limit payments to government providers to cost

Reduce payments for school-based services

Limit payments for rehabilitation services

Eliminate Medicaid graduate medical education payments

Subtotal, regulatory

Subtotal B, legislative & regulatory |

-5,000

-3,645

-2,290

-1,780

-12,715

-20,960 |

-11,960

-9,050

-4,260

-6,170

-31,440

-50,395 |

|

C. Other Budget Proposals |

|

Link payments to state performance results

Subtotal C, legislative (no regulatory) |

-330

-330 |

-1,380

-1,380 |

Total, legislative savings

Total, regulatory savings

Total,

regulatory and

legislative savings |

-12,010

-12,715

-24,725 |

-29,485

-31,440

-60,925 |

|

D. Medicaid Extensions** |

Legislative

Extend transitional Medicaid (TMA) through FY 2008

Extend qualified individuals (QIs) through FY 2008

Medicaid impact of extending SSI for refugees through FY 2010

Subtotal D, legislative (no regulatory)** |

665

425

99

1,189 |

665

425

99

1,189 |

|

Total, all legislative and regulatory changes** |

-23,536 |

-59,736 |

*These policies reduce federal payments to states or local governments. State or local governments may respond by reducing Medicaid or state/local expenditures or increasing taxes to compensate.

** This table does not include the Administration's SCHIP proposal or the effect of that proposal on Medicaid. These will be discussed in a forthcoming paper by Park and Broaddus.

Source: OMB, HHS and CMS budget documents, February 2007. This table does not include several proposals which were shown as having no budget impact. |

End Notes:

[1] In general, this paper discusses the effects of the budget proposals over the next five years because that is how the Administration has presented its budget proposals. Table 1on the last page includes information about both five- and ten-year effects. The Administration’s budget also proposes changes to the SCHIP program, which are discussed in Edwin Park and Matt Broaddus, “SCHIP Reauthorization: President’s Budget Would Provide Less than Half the Funds That States Need to Maintain SCHIP Enrollment,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, forthcoming February 2007.

[2] The Deficit Reduction Act reduced net federal Medicaid spending by $4.9 billion over five years and $26.5 billion over ten years.

[3] Andy Schneider, Leighton Ku, and Judith Solomon, “The Administration’s Medicaid Proposals Would Shift Federal Costs to States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 14, 2006.

[4] Iris Lav, “Federal Grants to States and Localities Cut Deeply in Fiscal Year 2008 Federal Budget,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 6, 2007.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Vernon Smith, et al. “Low Medicaid Spending Growth Amid Rebounding State Revenues,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2006.

[7] Federal Funds Information for States, “Impact of a Ceiling on Medicaid Administrative Cost Matching,” Feb. 13, 2007 provides further analysis of this proposal, including state-specific estimates of the impact.

[8] States also receive federal funds at a 90 percent matching rate for the development of claims processing and information systems and for administering the provision of family planning services.

9] 72 Fed. Reg. 2236 et seq., January 18, 2007.

10] The cost of extending these provisions for a full five years is considerably higher than the amounts proposed by the Administration. The Administration’s proposals are temporary solutions that leave the costs of future extensions to future year’s budgets.

11] Zoë Neuberger, “Loss of SSI Aid Is Impoverishing Thousands of Refugees: Congress Could Prevent Further Hardship,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Feb. 8, 2007. |

|

|

|

|

|

KEY FINDINGS:

The Administration’s budget would cut federal Medicaid funding by $25 billion over the next five years ($61 billion over the next ten years). The Administration’s budget would cut federal Medicaid funding by $25 billion over the next five years ($61 billion over the next ten years).

$21 billion of the $25 billion in federal savings would be accomplished by shifting costs from the federal government to the states. $21 billion of the $25 billion in federal savings would be accomplished by shifting costs from the federal government to the states.

To compensate for the loss of federal Medicaid funds, states would have to choose between cutting back on their Medicaid programs by reducing eligibility, benefits, or payments to providers; cutting back on other state programs and using those funds to replace federal Medicaid dollars lost; or increasing taxes. To compensate for the loss of federal Medicaid funds, states would have to choose between cutting back on their Medicaid programs by reducing eligibility, benefits, or payments to providers; cutting back on other state programs and using those funds to replace federal Medicaid dollars lost; or increasing taxes.

|

|

|

|