|

January 5, 2007

A $7.25 MINIMUM WAGE WOULD BE A USEFUL STEP IN HELPING WORKING FAMILIES ESCAPE POVERTY

By Jason Furman and Sharon Parrott

In the early 1990s there was basic agreement that parents working full time should not have to raise their children in poverty. While liberals and conservatives sometimes differed on the means to reach this goal, they agreed with the core principle.

The yardstick used to measure achievement of this goal was whether a minimum-wage earner in a family of four earned enough (after subtraction of payroll taxes), together with the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)[1] and food stamps, to have an income at or above the poverty line. (It should be noted that this is a very low floor. In 2006, the federal poverty line for a family of four was about $20,000, well short of what most Americans would consider a decent standard of living.)

As shown in Table 1, this goal was reached in the late 1990s, as a result of an EITC increase enacted in 1993 and a minimum-wage increase enacted in 1996. In 1998, a typical family of four with a full-time, minimum-wage worker had income above the poverty line when food stamps and EITC benefits were considered.

However, ten years of inflation have eroded the minimum wage to its lowest inflation-adjusted level in more than 50 years. As a result, in 2006 a family of four with one minimum-wage earner had a total income (including food stamps and the EITC) of $18,950, some $1,550 below the poverty line.

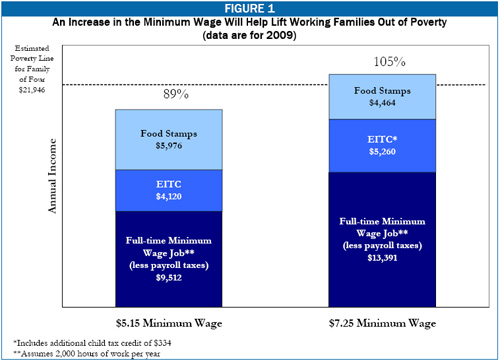

Raising the minimum wage from its current level of $5.15 an hour to $7.25 in 2009, as has been proposed, would ensure once more that a family of four with a parent working full time at the minimum wage does not have to raise its children in poverty (see Figure 1).[2] The increase would mean an additional $4,200 in annual earnings for a full-time, minimum-wage worker. It also would automatically trigger $1,140 in increases in the family’s EITC and refundable Child Tax Credit, enough to roughly offset the decrease in the family’s food stamp benefits resulting from the increase in the family’s cash income.[3] As a result, the family would be lifted 5 percent above the poverty line, instead of being 11 percent below the poverty line in 2009, as it would be under current law.[4]

|

Table 1:

Income for a Family of Four With One Full-Time, Minimum-Wage Earner |

| |

1998 |

2006 |

2009

$5.15 Minimum Wage |

2009

$7.25 Minimum Wage |

| Earnings |

$10,300 |

$10,300 |

$10,300 |

$14,500 |

| - Payroll Taxes |

-$788 |

-$788 |

-$788 |

-$1,109 |

| EITC |

$3,756 |

$4,120 |

$4,120 |

$4,926 |

| Refundable Child Credit |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$334 |

| Food Stamps |

$3,348 |

$5,316 |

$5,976 |

$4,464 |

| Total Income |

$16,616 |

$18,948 |

$19,608 |

$23,115 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| % of Federal Poverty Line |

[[101%] |

[[92%]] |

[[89%]] |

[[105%]] |

|

Note: Estimates for 2009 are based on the Congressional Budget Office’s projections of inflation.

|

It is important to note that if, as is expected, the minimum wage legislation does not index the wage for inflation after 2009, inflation will once again begin to erode the wage’s value. If no other changes are made, the family in this example will fall back below the poverty line by 2015.

Many Minimum-Wage Workers Will Remain Poor

While an increase in the minimum wage would raise the earnings of many workers and lift some families above the poverty line, some minimum-wage workers would remain poor. This includes many workers who experience periods of joblessness during the year. Low-wage workers often are ineligible for unemployment insurance when they lose their jobs; even when they are eligible, they often receive low benefits.

Moreover, some larger families with a full-time, minimum-wage worker would not be lifted above the poverty line by an increase in the minimum wage, even if they receive food stamps and the refundable tax credits for which they are eligible. While families with more children have larger needs — which is why the poverty line is set higher for larger families — wages (including the minimum wage) do not rise with family size. As a result, the poverty rate for families with three or more children is more than double the rate for families with one or two children.[5]

Even with a $7.25-an-hour minimum wage, a family of five with a full-time, minimum-wage earner that receives food stamps and the refundable tax credits would fall $1,139 below the poverty line in 2009. Families of more than five would fall even farther below the poverty line.[6] In part, this reflects the fact that while a larger EITC is provided to families with two or more children than to families with one child, no additional adjustment is provided for families with three or more children. (Various policy analysts have called for such adjustment, and policymakers as diverse as former Rep. Dick Armey and President Clinton have proposed it, but it has not been enacted.)

Food Stamps and the EITC Are Essential to Lifting Working Families Out of Poverty

Even with the increase in the minimum wage, a family of four will remain well below the poverty line unless it receives food stamp benefits, the EITC, and the Child Tax Credit. Without these benefits, the family’s earnings alone would leave it about $7,400 below the poverty line.

Unfortunately, many low-income working families that are eligible for these benefits do not receive them. While working families’ participation in the Food Stamp Program has increased in recent years — in part due to program simplifications made in 2002 to make it easier for eligible working families to receive food stamps — it remains low. Only 46 percent of households with earnings that were eligible for food stamps received them in 2004, the most recent year for which these data are available.

Some families with children that include a full-time, minimum-wage earner are ineligible for food stamps despite meeting the income-eligibility criteria. In most states, families with just $2,000 of savings are ineligible for food stamps, regardless of how low their incomes are. Similarly, many legal immigrant adults are ineligible for food stamps, regardless of their incomes, if they have lived in the United States for less than five years.

Participation rates are higher in the EITC than in the Food Stamp Program, but some families that are eligible for EITC benefits do not file for them.[7]

|

Nearly Half of Minimum-Wage Workers Are the Household’s Chief Breadwinner

Opponents of increasing the minimum wage often portray minimum-wage workers as middle-class teenagers. Some fit that description, but many others do not. Recent Census data show that among those workers likely to get a pay increase as a direct result of a minimum-wage increase:

- nearly half (48 percent) are the household’s chief breadwinner — that is, no higher-paid family members live with them; and

- nearly half (47 percent) were poor or near-poor in the prior year — that is, they lived in families with cash incomes below twice the poverty line.a

One reason many minimum-wage workers have low incomes is that they are not employed full-time throughout the year. Low-wage jobs often have high turnover rates, and low-wage workers sometimes have to leave their jobs to care for an ill family member or when child care arrangements fall through. Low-income working parents typically work close to full-time when they are employed, but have periods of joblessness over the course of the year.

a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculations of the March 2006 Current Population Survey. The 2006 data do not include information on food stamp receipt or refundable tax credits and, thus, only cash income can be analyzed. Data for 2005 does include information on these other forms of income; analysis of the 2005 data produced roughly the same results as are shown here. |

Families with Incomes Just Above the Poverty Line Have Difficulty Making Ends Meet

While the goal of lifting working families to the poverty line is a worthy one, families with incomes just above the poverty line also face real difficulties making ends meet. The poverty line was established in the 1960s and was calculated by multiplying the cost of feeding a family by three, under the assumption that families spend, on average, one-third of their income on food. The poverty line is a useful measure of income adequacy, particularly because it provides a historical look at the extent to which American’s incomes fell above or below a particular standard. But, the standard does not necessarily reflect the cost of raising a family today and families with incomes at the poverty line often struggle to meet their basic needs.

-

Housing. Housing cost burdens for poor families are often severe, and the cost of housing is likely to take far more than 30 percent of most low-income working families’ incomes — the government’s standard for housing affordability[8] — even after the minimum-wage increase takes effect. Nationwide, the average cost of a modest two-bedroom apartment in 2006 was $821 per month, or $9,852 per year, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). At this cost, rent and utilities consume nearly half (48 percent) of the income of a family of four at the poverty line.[9] Even if the proposed minimum-wage increase takes full effect in 2009, the cost of a modest two-bedroom apartment will consume an average of 46 percent of the total income of a family of four with a full-time, minimum-wage worker.[10] (This calculation assumes that the family receives food stamps, the EITC and child tax credit.)

-

Child care. Many working families face significant child care costs, and quality child care programs can be out of reach for low-income working families. According to the National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies, in the median state in the 2004-2005 academic year, full-time infant care in a licensed child care center cost an average of $7,100 per year, while full-time care for preschoolers in a licensed child care center cost an average of $5,800.[11] Without a child care subsidy, a family earning at or near the minimum wage is unlikely to be able to afford such a tuition bill for one child, let alone two or more children.

Unfortunately, due to a lack of funding, child care subsidy programs serve only a minority of those eligible for such assistance. Working families that need child care but cannot afford it and do not receive subsidies have few options — they can try to rely on friends and family for care or find lower-cost paid providers that likely offer lower-quality care.

-

Health care. Most children in families with a full-time, minimum-wage worker are eligible for free or low-cost health insurance through Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. However, most low-income working parents are not eligible for health insurance through these programs, and few have private coverage. In fact, in 25 states, a parent in a three-person family with a full-time, minimum-wage job earns too much to qualify for Medicaid.[12] Because of the lack of either public or private coverage, about 41 percent of all parents with incomes below the poverty line were uninsured in 2005, according to Census data. Adult low-wage workers who are not parents almost never are eligible for Medicaid coverage unless they have a severe disability. Some 45 percent of poor childless adults are uninsured.[13]

Evidence of the difficulties near-poor households have in making ends meet is found in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “food insecurity” data. In 2005, according to USDA, about one in seven households with incomes between 100 percent and 185 percent of the poverty line were uncertain of having, or unable to acquire, enough food because they had insufficient money and other resources for food .[14]

Building on a Higher Minimum Wage

Raising the minimum wage would be an important first step and a useful complement to public policies like the EITC, food stamps, and child care subsidies, which provide additional benefits and supports for low-income working families. A broader agenda is needed, however, to raise the prospects of low-wage workers and their families more significantly. Such an agenda would need to include additional income supports, help in obtaining the health care, child care, and housing that these families need but often cannot afford, and new opportunities to attend college or upgrade their skills so they can secure higher paying, more stable jobs.

End Notes:

[1] When this definition was developed, the federal Child Tax Credit did not exist. This credit is included with the EITC in this analysis.

[2] Under the proposal, the minimum wage increase would be phased in over the next two years, rising to $5.85 sixty days after enactment; $6.55 twelve months after that; and $7.25 in another twelve months.

[3] Food stamp benefits are based on a household’s income — as income rises and families can afford to purchase more food, benefits fall. For every dollar of additional earnings, households lose between 24 and 36 cents in food stamp benefits.

[4] Raising the minimum wage would mean that a full-time, minimum-wage worker would qualify for the refundable Child Tax Credit. In 2007, such workers do not qualify because the credit is only refundable for those with earnings above $11,750.

[5] CBPP calculations based on the March 2006 Current Population Survey.

[6] In part, this reflects the fact that while a larger EITC is provided to families with two or more children than to families with one child, no additional adjustment is provided for families with three or more children. Such an adjustment has been proposed by various policy analysts and by policymakers as diverse as former Rep. Dick Armey and President Clinton.

[7] See "The Earned Income Tax Credit at Age 30: What We Know," Steve Holt, The Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program, Research Brief, February 2006, http://www.brookings.edu/metro/pubs/20060209_Holt.htm.

[8] See Out of Reach, National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2005, http://www.nlihc.org/oor/oor2005/index.cfm. NLIH’s calculation of the national average cost of a two-bedroom apartment is based on HUD’s Fair Market Rent estimates.

[9] Note that under these standards, refundable tax credits and food stamps are not included as income or when determining housing affordability.

[10] CBPP calculated the average fair market rent in 2009 using CBO inflation projections for overall inflation.

[11] See http://www.naccrra.org/randd/data/2004-2005PriceofCare.pdf.

[12] Donna Cohen Ross and Laura Cox, "In a Time of Growing Need: State Choices Influence Health Coverage Access for Children and Families," Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Oct. 2005.

[13] CBPP analyses of March 2006 Current Population Survey data.

[14] Mark Nord, Margaret Andrews, and Steven Carlson, Household Food Security in the United States, 2005, Economic Research Report No. 29, November 2006, http://www.ers.usda.gov/Publications/ERR29/. |