ACCELERATING TOP RATE REDUCTIONS IS INEFFECTIVE

STIMULUS

AND REDUCES FLEXIBILITY TO ADDRESS FUTURE BUDGET CHALLENGES

By Joel Friedman

| PDF of this report HTM of fact sheet PDF of fact sheet |

| If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The Bush Administration’s “growth package” includes a proposal to accelerate the scheduled rate reductions for the top four brackets of the individual income tax. This proposal represents a poorly targeted and inefficient means of stimulating the economy, because most of its cost occurs in years after the economy is expected to have recovered and because it would predominately benefit high-income tax filers who are more likely to save a portion of these funds than inject them into the economy now by immediately increasing their spending.

- Over half of the benefits of this tax cut would flow to the top one percent of tax filers in 2003, and over 35 percent would go to those with incomes exceeding $1 million, who would receive an average tax cut from this provision alone of $63,400 in 2003.

- Overall, the distribution of accelerating the top rate reduction is even more skewed than the Administration’s proposal to exempt corporate dividends from individual taxes.

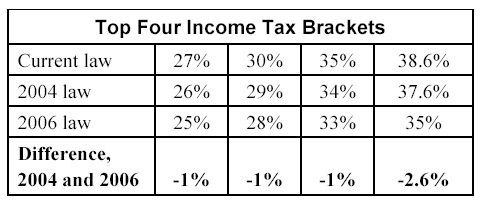

Although it has received less attention in the media than the proposed dividend tax cut, accelerating the reduction in the upper-bracket rates — and particularly the top rate, which is scheduled to be reduced much more than the other rates in 2006 (see table) — is a key component of the Administration’s new package. As Reagan Administration economic adviser Martin Anderson has noted with regard to the Administration’s new proposal, “Even if [President Bush] does not get all he wants on eliminating the tax on stock dividends, if he gets the income tax cuts, it’s a total victory. He wins big.”[1]

Once these rate cuts are locked in place, any calls to roll them back will be labeled a tax increase, rather than viewed as simply postponing or canceling tax cuts not yet in effect. Indeed, locking in these lower rates now may essentially remove them from future debates on how to address deficits that threaten to mount to unmanageable levels as a result of a combination of tax cuts, the impending retirement of the baby boom generation, pressure for a prescription drug benefit for seniors, growing homeland security needs, and a possible war and subsequent nation-building in Iraq. Accelerating the rate cuts so they take effect in 2003 would exempt the rate cuts from scrutiny during the 2004 election cycle, where one would otherwise expect an active debate on the affordability of these rate cuts in a budget environment that has deteriorated sharply.

The long-term implications for the budget of this proposal go well beyond its official cost of $74 billion as estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation. Rather, making the 2006 rates effective immediately increases the likelihood that the lower rates will be made permanent; that would cost, for example, over $200 billion more through 2013 than if the 2004 rates were made permanent instead.

Most Costs Occur After 2003

The current top four marginal rate brackets for the individual income tax are 27 percent, 30 percent, 35 percent, and 38.6 percent — or 1 percentage point lower than prior to enactment of the 2001 tax cuts. In 2004, each of these upper-bracket rates is scheduled to be reduced by another 1 percentage point. In 2006, the top rate is set to fall by another 2.6 percentage points — from 37.6 percent to 35 percent — while the remaining three rates would be reduced by one additional percentage point (to 25 percent, 28 percent, and 33 percent, respectively).

The Administration’s proposal to accelerate these rate reductions, so the lower 2006 rates would take effect in 2003, would be ineffective stimulus for two basic reasons. First, the proposal is poorly designed to provide stimulus to the economy now, when it is most in need of a boost. Only 13 percent of its official $74 billion cost would occur in fiscal 2003, when the economy is most in need of stimulus.[2] The remainder would occur in fiscal years 2004, 2005, and 2006 — all years when the recovery is expected to be underway.

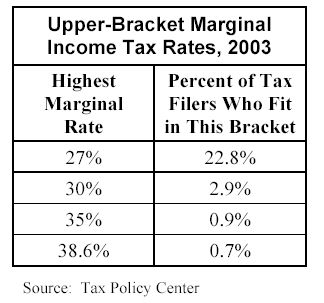

Second, the effectiveness of this proposal as

economic stimulus is further diminished because it disproportionately

benefits the highest-income tax filers. As the Congressional

Benefits Are Concentrated at the Very Top of the Income Spectrum

According to the

As a result, the

- Nearly 54 percent of the benefits of accelerating the four upper-bracket rate reductions would flow to the top one percent of tax filers, a group whose incomes exceed $330,000 and whose average income is about $1 million.

- Nearly 82 percent of the benefits would flow to the top ten percent of filers, who have incomes over $100,000.

- Over 35 percent of the tax-cut benefits would flow to the 0.2 percent of tax filers whose income exceeds $1 million. Each of these high-income filers would receive an average tax cut of more than $63,400 in 2003, just from the proposal to accelerate the rate reductions.

Of all of the proposals in the President’s “growth package,” accelerating implementation of the upper-bracket rates showers the most benefits on those with the highest incomes. Its benefits are even more concentrated at the top that the proposal to eliminate individual taxes on corporate dividends.

Reduces Flexibility of Policymakers

Implementing the 2006 rate reductions in 2003 significantly reduces the flexibility of policymakers over the next few years to address fiscal issues. If the rate cuts are not accelerated, there is little doubt that the 2004 rate reductions will go into effect as scheduled. Any effort to delay their implementation would be unlikely to pass Congress. Even if it did, it would meet a certain veto from President Bush. But the 2006 rate reductions are not scheduled to go into effect until after the 2004 elections and thus will almost certainly be part of the policy debate over budget priorities that inform those elections. Implementing the 2006 rate reductions now would forestall this debate.

Accelerating implementation of the 2006 rate reductions negates one of the advantages of the gradual phasing in of the tax-cut provisions enacted in 2001, which allows policymakers to take into account new developments that affect the budget when determining whether scheduled tax cuts are still affordable. Since the 2001 package was enacted, the budget outlook has deteriorated sharply, with sizeable surpluses being replaced by deficits. Recent estimates prepared by the Congressional Budget Office for Senator Voinovich show that once this year’s appropriations levels are taken into account and expiring tax provisions are extended, the ten-year surplus is essentially eliminated.[7] Moreover, pressures on the budget — from the ongoing fight against terrorism at home and a possible war against Iraq and its aftermath, to the generally agreed-upon need for a prescription drug benefit for seniors — continue to mount. Plus, the baby boom generation begins to retire and draw Social Security benefits in 2008, only five years from now.

The Administration’s proposal to accelerate the 2006 upper-bracket rates reductions and implement them now poses long-term fiscal dangers, as it increases the likelihood that these lower rates will take effect and then be made permanent. The cost of setting the rates at the 2006 level rather than at the 2004 levels, for example, would be more than $200 billion through 2013, in terms of lost revenues and increased debt service costs.[8] Once the 2006 rates take effect, they will be very difficult to change regardless of fiscal conditions.

In summary, the Administration’s proposal to accelerate the reductions in the upper-bracket rates would be ineffective at stimulating the economy in the short run. Worse, it would sharply limit the flexibility of policymakers as they seek ways to address the increasingly worrisome long-term budget conditions the nation faces.

End Notes:

[1]

Donald Lambro, “

[2]

Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue

Provisions Contained In The President’s Fiscal Year 2004 Budget

Proposal,”

[3]

Congressional

[4]

In addition, the

[5]

Under the President’s proposal, a married couple with two children would

not begin to benefit from the upper-bracket rate reductions until its

income exceeds $78,500. This is higher than under current law because

of the effects of the Administration’s plan to accelerate provisions

enacted in 2001 related to the child tax credit, the 10 percent bracket,

and marriage penalty relief.

[6]

The

[7]

Congressional Budget Office, “Letter to Senator George V. Voinovich,”

[8]

These estimates rely on Joint Committee on Taxation cost estimates.

The estimates assume that the cost of both the 2004 rate reductions and

the 2006 rate reductions remain constant as a share of the economy

through 2012. Implicit in this assumption is that these permanent

rate reductions will be accompanied by the type of adjustment to the

Alternative Minimum Tax that the Administration included in its economic

package, but only through 2005. Reducing these upper-bracket

rates has the effect of pushing more tax filers on to the AMT; only by

increasing the AMT exemption or making other adjustments to the AMT can

this be avoided.