Debate over Causes of Deterioration of

Surplus Marred

by Failure to Distinguish Between Short-Term and Long-Term Impacts

by Joel

Friedman and Robert Greenstein

| Recent Comments on the

Deteriorating Budget Outlook Do Some in Washington Want to Raise Your Taxes? PDF of this report If you cannot access the files through the links, right-click on the underlined text, click "Save Link As," download to your directory, and open the document in Adobe Acrobat Reader. |

The deterioration in the budget outlook is now widely acknowledged. Yet efforts to identify the cause of the disappearance of projected surpluses have been marked by confusion between what is happening to the budget this year and what is happening over the coming decade.

- In a January 4 speech, Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle asserted that the tax cuts enacted last year are the "biggest reason" for the erosion of the budget surpluses that were projected at the beginning of 2001. Citing Budget Committee estimates that the 10-year budget surplus had shrunk by $3.7 billion, Daschle maintained the tax cut was the "largest factor."

- In contrast, Congressional Republicans and Administration officials have pointed to the role of the recession and said that it, rather than the tax cut, is the principal reason for the drop in the surplus. According to Senator Don Nickles, the Assistant Republican Leader in the Senate, more than two-thirds of the reduction in the surplus this year is the result of the recession. Similarly, Treasury Secretary O'Neill recently stated that only one-quarter of this year's drop in the surplus is due to the tax cut.

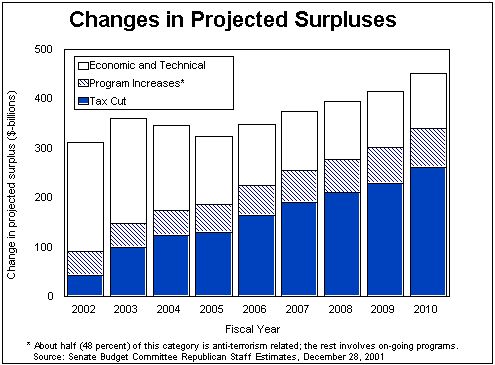

Despite reaching what may sound like sharply discordant conclusions, these statements all are largely accurate, based on the best available evidence. In the short term, the recession is unquestionably the biggest cause of the return to budget deficits. But in the latter part of the decade — when the economy is assumed to have recovered from the current slowdown — and over the course of the decade as well, the tax-cut package enacted last year is the single largest factor responsible for the deteriorating budget outlook. Recent estimates prepared by the Republican staff of the Senate Budget Committee show that:

- The tax-cut package enacted last year accounts for about one-eighth of the deterioration in the surplus in 2002.

- But in each of the years after 2006, the tax cut accounts for more than half of the reduction in the surplus. By 2010, nearly three-fifths of the reduction is due to the tax cut.

- For the period between 2002 and 2011, the tax cut accounts for 44 percent of the reduction in the surplus —and is the single largest factor behind the shrinkage of the surplus.(1)

That the recession, rather than the tax cut, is the largest cause of the return to deficits in the next year or two is not surprising. It is reasonable policy for the federal government to run a deficit when the economy falls into recession. The federal government acts as an "automatic stabilizer" for the economy, helping to soften the impact of recessions by allowing revenues to fall as personal and corporate incomes decline and allowing expenditures to increase as demand for certain programs, such as unemployment insurance, rises. Indeed, running higher deficits or smaller surpluses during a downturn helps to stimulate the economy.

Fortunately, the effects of the automatic stabilizers are temporary, coinciding with the economic downturn. As the economy recovers, incomes rise and revenues rebound, while expenditures for programs like unemployment insurance contract. What is so troubling about the recent dramatic deterioration in the nation's fiscal outlook is not the return to deficits while the economy is down but the very large decline in the surplus in years after the economy is projected to have recovered, when the effects of the recession on the budget will have faded. It is the much smaller surpluses in those years that represent a permanent deterioration in the nation's fiscal health. To take corrective steps, it is crucial to understand the factors behind the worsening budget outlook in the years after the downturn is over.

Recent Comments on the Deteriorating Budget Outlook Democratic Comments

Republican Comments

|

Importance of Ten-year Estimates

In attempting to highlight the role of the recession in eating up the surplus, Administration officials appear to be going beyond focusing attention on the budget in the current year. They also appear to be endeavoring to undermine the credibility of ten-year budget projections. Secretary O'Neill stated on Meet the Press on January 6, for instance, that "people who believe as a religion in 10-year numbers haven't lived in the real economy....And so to make a big deal out of 10 years seems to be to be a false idea." Commerce Secretary Donald Evans echoed these comments, arguing that any attempt to project the budget even over the next three to five years "is pure speculation at this point."

To be so dismissive of the budget projections for the next decade, however, ignores an important point that has been raised by both former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, as well as by Senator Daschle in his recent speech.(2) Because the bond market responds to changes in projected government borrowing, the high cost of the tax cut when it is in full effect — which will slow efforts to reduce the debt and thereby increase the government's need to borrow funds in the bond market — has helped to keep long-term interest rates higher than they otherwise would be. These higher long-term interest rates have an immediate impact; they raise the cost of borrowing for mortgages and various other investments and thus dampen current economic activity. As a result, the long-term cost of the tax cut lessens the effectiveness of efforts by the Federal Reserve and Congress to inject stimulus into the economy now to promote a more rapid recovery.

Furthermore, efforts by the Administration to denigrate ten-year budget projections stand in stark contrast to the Administration's own position a year ago. At that time, when President Bush was presenting his new budget, the Administration pointed to the large surpluses projected over the next ten years as justification for its policies. In fact, the Administration expressed strong concern that by the end of the decade, the large surpluses would cause the government to retire all of the available debt, thereby forcing it to purchase private assets with its excess cash, an option the Administration vigorously opposed. The Administration's first budget document, "A Blueprint for New Beginnings," stated that the Administration was proposing its large tax cut as part of "an agenda for gradually reducing the on-budget surplus in order to minimize the risks of a build-up of excess cash and Government purchase of private assets in the future." Moreover, in his first major address to Congress and the nation on February 27, 2001, President Bush stated that the nation had ample funds to establish a Medicare prescription drug benefit, increase funding for education and various other initiatives, pay down most of the debt, and still finance his tax cut. The basis for this claim was the Administration's ten-year budget estimates.

Do Some in Washington Want to Raise Your Taxes? In a speech in California on January 5, President Bush asserted that "[t]here's going to be people who say, we can't have the tax cut go through anymore. That's a tax raise." He added: "Not over my dead body will they raise your taxes." While President Bush made a strong political statement, he did little to help clear away the confusion stemming from the failure to distinguish short-term stimulus proposals from longer-term policy changes or to distinguish the impact of various policy proposals on the budget and the economy today from the impact in years after the economy has recovered. All of the budget proposals currently under discussion to stimulate the sagging economy call for cutting taxes, not raising them. The Administration's plan, the House-passed bill, and the Senate Finance Committee proposal all include tax cuts. In his January 4 speech, Senate Majority Leader Daschle reiterated his support for temporary tax cuts to help revive the economy and proposed a new tax cut aimed at lowering the cost of labor for businesses. There are no proposals on the table to raise taxes to eliminate near-term deficits; a tax increase of this kind runs counter to a broad consensus of economic advice concerning the appropriate fiscal policy to undertake when the economy is in recession. To be sure, some in Washington have called for deferring or cancelling some portions of last year's tax-cut legislation that have not yet gone into effect. The most widely discussed proposal is to defer or cancel implementation of scheduled future reductions in some of the upper-bracket tax rates. Those rate reductions are not scheduled to take effect until 2004 and 2006, long after the recession is expected to be over. As a result, deferring or cancelling those rate reductions would not affect tax collections during the current downturn. Nor would such proposals raise tax rates above their current levels. The top tax rate was reduced from 39.6 percent to 38.6 percent in 2002. Under the tax cut enacted in June, this rate would be reduced further in future years, falling to 35 percent in 2006. Cancelling these future reductions — which would affect only the top one percent of tax filers — would maintain the top rate at its current level of 38.6 percent. Such an action, which would save about $90 billion through 2011, would not increase tax rates above today's levels. Finally, even if one labels the cancellation of a future rate reduction a "tax increase," it cannot be equated with an immediate increase in taxes. The impact on the economy of cancelling a future rate reduction is very different from the impact of instituting a tax increase today. An immediate increase in taxes, such as an increase in tax rates in 2002, would likely worsen the recession by siphoning money out of the economy now and thereby further depressing consumer demand and business investment. By contrast, deferring or cancelling rate reductions not scheduled to take place for two to four years would take no money out of the hands of consumers and businesses during the current downturn. Moreover, it would improve the long-term budget outlook, which, in turn, could have the positive effect of putting downward pressure on long-term interest rates now. For this reason, some experts such as former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin have advised that the reduction in long-term interest rates likely to result from the cancellation of future tax rate reductions would help to stimulate the economy today, since the resulting reduction in long-term interest rates would lower the cost of financing business investments and consumer purchases. |

If ten-year projections are so uncertain as not to be worthwhile, there was little basis last spring for the magnitude of the Administration's ten-year tax cut. Last year, however, the Administration seemed to have few doubts about the validity of ten-year forecasts. Many budget watchdog organizations, such as the Concord Coalition and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, warned at that time that considerable uncertainty surrounded these ten-year estimates and that it would be far more prudent to enact a smaller tax cut until it was clear the projected surpluses would actually materialize. At the time, the Administration brushed aside these concerns, claiming that "there are convincing reasons to assume that higher revenues are more likely than lower revenues and a larger, not smaller, surplus lies ahead." It is only now that the ten-year projections are not so rosy — and that the projections suggest the tax cut was excessive — that the Administration seems to have lost faith in them.

It is fair for the Administration to point to the outsized role of the recession in causing deficits over the next couple of years. But neither the Administration nor other policymakers should ignore the role of the tax cut in reducing projected surpluses over the decade as a whole. It is primarily the cost of the tax cut — rather than the impact of the recession or the cost of the war or increased homeland security — that is responsible for the deterioration in the budget picture in the later years of the decade.

End Notes:

1. This conclusion may not be readily apparent from the table released by the Republican staff of the Senate Budget Committee, because the higher interest costs that can be attributed to the economic and technical reestimates and to the tax cut were displayed differently on the table. In the table, the SBC Republican staff combined the cost of the economic and technical reestimates and the higher debt service costs associated with these reestimates. For the tax cut, however, the table showed the revenue loss from the tax cut and the resulting higher debt service costs separately. When the debt service costs associated with the tax cut are combined with the revenue losses — and thus presented on the same basis as the economic and technical reestimates — the tax cut becomes the largest factor in the decline of the surplus over the decade. To assess the full impact on the surplus or deficit of a particular policy (such as the tax cut), it is necessary to include in the total the change in interest costs that flow automatically from that policy. (A forthcoming Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis by Richard Kogan will address these issues is more detail.)

2. Chairman Greenspan has noted the link between budget surpluses and long-term interest rates on numerous occasions. For instance, see his comments before the House Budget Committee on March 2, 2001; the Senate Banking Committee on July 24, 2001; and the Senate Finance Committee on September 20, 2001; and in a speech at the Bay Area Council Conference on January 11, 2002.