- Home

- Testimony Of Stacy Dean, Vice President ...

Testimony of Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy Before the House Committee on Agriculture's Subcommittee on Department Operations, Oversight, and Nutrition

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, non-profit, nonpartisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s food assistance work focuses on improving the effectiveness of the major federal nutrition programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). I also lead our work on program integration and efforts to facilitate and streamline low-income people’s enrollment into the package of benefits for which they are eligible. This includes directing technical assistance to state officials through the Work Support Strategies Initiative run by the Urban Institute and the Center for Law and Social Policy. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities receives no government funding.

My testimony today focuses on SNAP’s relationship to other federal programs.[1] SNAP is highly responsive to other federal assistance programs in the way that it assesses eligibility and benefit levels. This ensures that its benefits are targeted to those who struggle the most to afford a nutritious diet. And, other programs are keenly aware of SNAP’s ability to scrutinize the financial circumstances of low-income households. As a result, numerous programs rely upon SNAP’s determinations of eligibility and assessment of individual circumstances when setting their own eligibility rules and procedures. Moreover, SNAP is a significant program with a broad reach and high and proscribed standards for how benefits must be processed. As a result, SNAP is a highly influential program as states seek to coordinate the delivery of health and human services across many programs.

My testimony will focus on four areas:

- SNAP is a very effective program that alleviates poverty and hunger as well as improves its participants’ long-term outcomes.

- States and USDA operate SNAP very efficiently and with a high degree of accuracy in addition to the program’s rigorous eligibility assessment of participants.

- SNAP’s benefit calculation is very sensitive to households’ receipt of other assistance programs, ensuring that benefits are targeted to those that struggle the most to afford an adequate diet.

- Other programs benefit from SNAP’s robust and high-quality eligibility determination process. SNAP participation and the verified data used in a SNAP eligibility determination can be and is used by other programs to streamline their own eligibility and enrollment processes.

SNAP Plays a Critical Role in Our Country

Before turning to today’s hearing topic of the role SNAP plays in other federal assistance programs, I think it is important to review some of SNAP’s most critical features. As of April of this year, SNAP was helping more than 46 million low-income Americans to afford a nutritionally adequate diet by providing them with benefits via a debit card that can be used only to purchase food. On average, SNAP recipients receive about $1.40 per person per meal in food benefits. One in seven Americans is participating in SNAP — a figure that speaks both to the extensive need across our country and to SNAP’s important role in addressing it.

Policymakers created SNAP to help low-income families and individuals purchase an adequate diet. It does an admirable job of providing poor households with basic nutritional support and has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States.

When the program was first established, hunger and malnutrition were much more serious problems in this country than they are today. A team of Field Foundation-sponsored doctors who examined hunger and malnutrition among poor children in the South, Appalachia, and other very poor areas in 1967 (before the Food Stamp Program was widespread in these areas) and again in the late 1970s (after the program had been instituted nationwide) found marked reductions over this ten-year period in serious nutrition-related problems among children. The doctors attributed a significant part of this reduction to the Food Stamp Program (as the program was then named). Findings such as this led then-Senator Robert Dole to describe the Food Stamp Program as the most important advance in the nation’s social programs since the creation of Social Security.

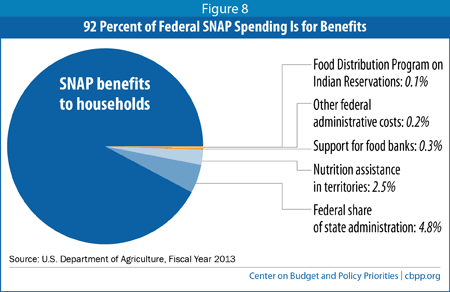

Consistent with its original purpose, SNAP continues to provide a basic nutrition benefit to low-income families, elderly, and people with disabilities who cannot afford an adequate diet. In some ways, particularly in its administration, today’s program is stronger than at any previous point. By taking advantage of modern technology and business practices, SNAP has become substantially more efficient, accurate, and effective. While many low-income Americans continue to struggle, this would be a very different country without SNAP.

SNAP Protects Families From Hardship and Hunger

SNAP benefits are an entitlement, which means that anyone who qualifies under the program’s rules can receive benefits. This is the program’s most powerful feature; it enables SNAP to respond quickly and effectively to support low-income families and communities during times of economic downturn and increased need. Enrollment expands when the economy weakens and contracts when the economy recovers.

As a result, SNAP can respond immediately to help families and to bridge temporary periods of unemployment or a family crisis. If a parent loses her job, SNAP can help her feed her children until she is able to improve her circumstances. A U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) study of SNAP participation over the mid-2000’s found that more than half of all new entrants to SNAP participated for less than one year and then left the program when their immediate need passed.

SNAP’s ability to serve as an automatic responder is also important when natural disasters strike. States can provide emergency SNAP within a matter of days to help disaster victims purchase food. After the 2005 hurricanes, for example, SNAP provided more than 2 million households with almost $1 billion in temporary food assistance. In 2013, SNAP helped households affected by Hurricanes Isaac and Sandy, tornadoes in Oklahoma, and flooding in Colorado, and in 2014 it has helped households in the Southeast affected by severe storms.

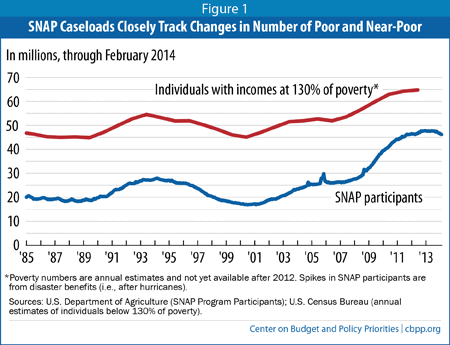

SNAP’s caseloads grew in recent years primarily because more households qualified for SNAP because of the recession, and because more eligible households applied for help. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has confirmed that “the primary reason for the increase in the number of participants was the deep recession . . . and subsequent slow recovery; there were no significant legislative expansions of eligibility.”[2]

While this increase in participation and spending was substantial, SNAP participation and spending have begun to decline as the economic recovery has begun to reach low-income SNAP participants. In 2013, SNAP growth began to stabilize, and by April 2014, the number of SNAP participants had fallen by 1.5 million since the peak of SNAP participation in December 2012. SNAP spending is also falling. In November 2013, a temporary benefit boost that was part of the 2009 Recovery Act ended, and as a result, SNAP spending on benefits will fall by about $5 billion in fiscal year 2014. Over the first nine months of fiscal year 2014 (October 2013 through June 2014), SNAP outlays were 7 percent lower than the same period of fiscal year 2013 on a nominal basis. CBO predicts that this trend will continue, and that SNAP spending as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will fall to its 1995 levels by 2019.

SNAP Lessens the Extent and Severity of Poverty and Unemployment

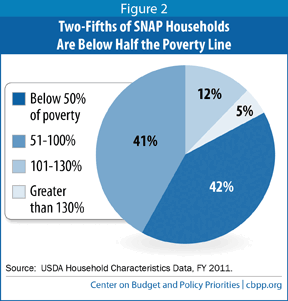

While the targeting of benefits adds some complexity to the program, it helps ensure that SNAP provides the most assistance to the poorest families with the greatest needs.

These features make SNAP a powerful tool in fighting poverty. A CBPP analysis using the government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which counts SNAP as income, found that SNAP kept 4.9 million people out of poverty in 2012, including 2.2 million children. SNAP lifted 1.4 million children above 50 percent of the poverty line in 2012, more than any other benefit program.

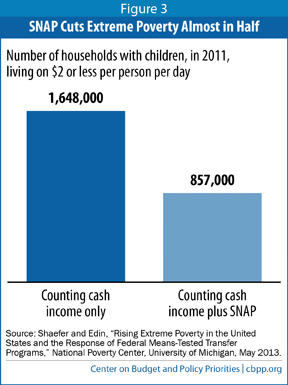

SNAP is also effective in reducing extreme poverty. A recent study by the National Poverty Center estimated the number of U.S. households living on less than $2 per person per day, a classification of poverty that the World Bank uses for developing nations. The study found that counting SNAP benefits as income cut the number of extremely poor households in 2011 by nearly half (from 1.6 million to 857,000) and cut the number of extremely poor children by more than half (from 3.6 million to 1.2 million).

SNAP is able to achieve these results because it is so targeted at very low-income households. Over 91 percent of SNAP benefits go to households with incomes below the poverty line, and 55 percent goes to households with incomes below half of the poverty line (about $9,895 for a family of three in 2014).

During the deep and prolonged recession and weak recovery, SNAP has become increasingly valuable for the long-term unemployed as it is one of the few resources available for jobless workers who have exhausted their unemployment benefits. In 2010, according to the Joint Economic Committee, over 20 percent of those who had been unemployed for more than six months received SNAP benefits. Nearly 25 percent of households in which someone’s unemployment benefits ended were enrolled in SNAP.

SNAP Improves Long-term Health and Self-sufficiency

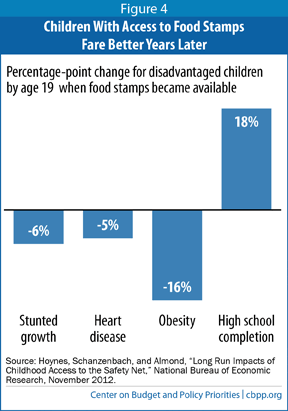

A recent National Bureau of Economic Research study examined what happened when government introduced food stamps in the 1960s and early 1970s and concluded that children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health outcomes as adults years later, compared with children born at the same time in counties that had not yet implemented the program. Along with lower rates of “metabolic syndrome” (obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes), adults who had access to food stamps as young children reported better health, and women who had access to food stamps as young children reported improved economic self-sufficiency (as measured by employment, income, poverty status, high school graduation, and program participation).[3]

Supporting and Encouraging work

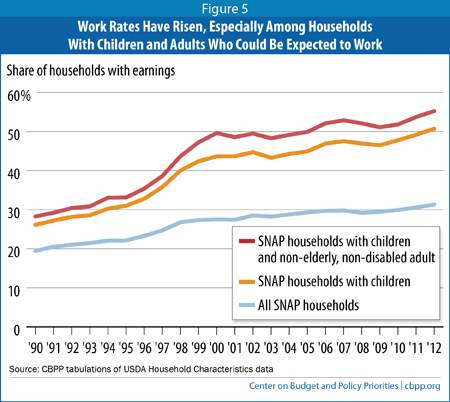

The number of SNAP households that have earnings while participating in SNAP has more than tripled — from about 2 million in 2000 to about 6.9 million in 2012. The share of SNAP families that are working has also been rising — while only about 28 percent of families with an able-bodied adult had earnings in 1990, 55 percent of those families were working in 2012. The increase was especially pronounced during the recent deep recession, suggesting that many people have turned to SNAP because of under-employment — for example, when one wage earner in a two-parent family lost a job, when a worker’s hours were cut, or when a worker turned to a lower-paying job after being laid off.

In addition, the SNAP benefit formula contains an important work incentive. For every additional dollar a SNAP recipient earns, her benefits decline by only 24 to 36 cents — much less than in most other programs. Families that receive SNAP thus have a strong incentive to work longer hours or to search for better-paying employment. States further support work through the SNAP Employment and Training program, which funds training and work activities for unemployed adults who receive SNAP.

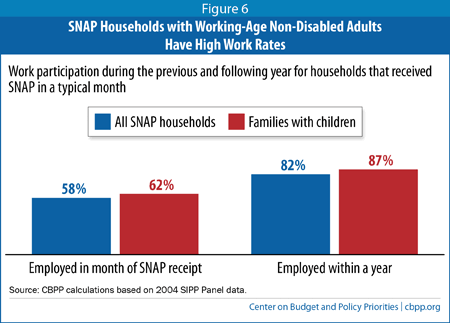

Most SNAP recipients who can work do so. Among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and more than 80 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. The rates are even higher for families with children. (Almost 70 percent of SNAP recipients are not expected to work, primarily because they are children, elderly, or disabled.)

SNAP Supports Healthy Eating

While I’ve focused so far primarily on SNAP’s role in reducing poverty, responding to downturns, and supporting work, we should not forget that SNAP enables low-income households to afford a healthier diet. Because SNAP benefits can be spent only on food, they raise families’ food purchases more than an equivalent amount of cash assistance would. Fruits and vegetables, grain products, meats, and dairy products comprise almost 90 percent of the food that SNAP households buy. In addition, all states operate SNAP nutrition education programs to help participants make healthy food choices.

Strong Program Integrity

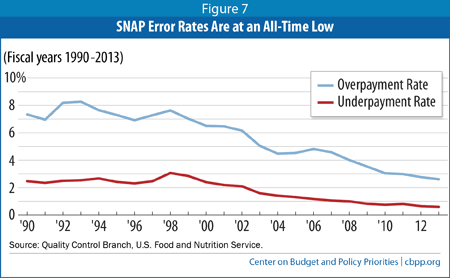

SNAP has one of the most rigorous payment error measurement systems of any public benefit program. Each year states take a representative sample of SNAP cases (totaling about 50,000 cases nationally) and thoroughly review the accuracy of their eligibility and benefit decisions. Federal officials re-review a subsample of the cases to ensure accuracy in the error rates. States are subject to fiscal penalties if their error rates are persistently higher than the national average.

If one subtracts underpayments (which reduce federal costs) from overpayments, the net loss to the government last year from errors was about 2 percent of benefits.

In comparison, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates a tax noncompliance rate of 16.9 percent in 2006 (the most recently studied year). This represents a $450 billion loss to the federal government in one year. Underreporting of business income alone cost the federal government $122 billion in 2006, and small businesses report less than half of their income.[5]

The overwhelming majority of SNAP errors that do occur result from mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers, not dishonesty or fraud by recipients. In addition, states have reported that almost 60 percent of the dollar value of overpayments and almost 90 percent of the dollar value of underpayments were their fault, rather than recipients’ fault. Much of the rest of overpayments resulted from innocent errors by households facing a program with complex rules.

SNAP’s Relationship With Other Programs

Now that I have reviewed some of SNAP’s most critical features, I’ll discuss how SNAP is influenced by and influences other programs. I’ll focus on two aspects of how SNAP relates to other federal assistance programs:

- One, SNAP’s benefit structure is highly responsive to other forms of assistance that households may receive; and

- Two, SNAP is a part of a larger health and human services system, and state administrators work to coordinate its delivery and program rules with other programs where appropriate. Other programs can rely upon SNAP’s rigorous and high-quality assessment of a household’s financial circumstances. These efforts can result in far more efficient application and enrollment systems as well as be the means to connect struggling families and seniors seamlessly to the benefits that can help them. Moreover, because SNAP’s assessment of eligibility is robust, using its eligibility determination or verified information can increase program integrity and accountability in other programs.

SNAP’s Benefit Design Is Highly Responsive to Other Federal Assistance Programs

Of course, people cannot survive solely on SNAP benefits alone. Many individuals and families whose circumstances qualify them for SNAP also meet the eligibility criteria for other programs. SNAP’s low-income senior population typically has income from Social Security or Supplemental Social Security (SSI) benefits. Unemployed individuals may combine SNAP with unemployment insurance benefits to cover their monthly expenses. Working families with children who participate in SNAP may also receive subsidies to cover their child care costs from the limited funding of the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDF). Because SNAP is the program of last resort, it calculates food assistance benefit levels to households after capturing their available income to purchase food (while no other program may count SNAP as income). This approach enables it to wrap around the benefits of other safety net programs and to help fill in many of the gaps. SNAP targets its benefits to the households that have the fewest resources available to afford an adequate diet. Several features set SNAP apart among programs:

Its national benefit structure is responsive to other programs. Unlike many other benefit programs, which are restricted to particular categories of low-income individuals (such as senior citizens, people with disabilities, families with children, veterans, or people who recently became unemployed), SNAP is broadly available to almost all households with low incomes. SNAP eligibility rules and benefit levels are, for the most part, set at the federal level and uniform across the nation. These SNAP features ensure that poor families have adequate nutritional resources regardless of where they live. The amount of a family’s SNAP benefits depend on its income, and as a result, SNAP benefits tend to be higher in states with below-average wages and cash assistance benefits. The program narrows disparities between low-income families and communities in poorer states and those in more affluent states. This aspect of SNAP is especially important to southern states and rural areas, where wages (as well as cash assistance benefits) tend to be lower. For example, cash assistance benefits for families with children that have no other income are about four times higher in states that make the highest cash assistance payments than in the lowest-payment states. When SNAP benefits are added in, this disparity narrows to less than 2-to-1.

It reflects other programs’ income to households. SNAP counts cash income from all sources, including earnings from a job as well as unearned income, such as cash assistance, Social Security, unemployment insurance, and child support. Thus, households that qualify for and receive benefits from other federal or state programs receive lower SNAP benefits than households that have no other cash income available to purchase food. This helps to ensure, for example, that a family with a single parent who loses her job and cannot find a new job before her unemployment insurance ends still has resources available to purchase an adequate diet for her children.

It allows deductions to help ease inequities. SNAP also targets benefits by allowing deductions from income for the cost of certain essential household expenses (such as rent and child care) before determining benefits. For example, although earning a low income makes many workers eligible for child care and housing assistance, only a small number are able to participate in these programs because of capped federal funding.

Consider two families that live next door to each other: if one receives a housing voucher or a subsidy to help afford child care costs but the other does not, the latter family may have to spend more than half of its income on its shelter or child care expenses. As a result, that family will have considerably less money available to buy food. SNAP helps to partially address this inequity by allowing the household without the subsidy to deduct a portion of the housing or child care expense from its income and receive a higher SNAP benefit. While this targeting of benefits adds some complexity to the program, it is critical in focusing assistance more effectively on those in greatest need.

To be sure, there are some exceptions to this framework to eliminate inequities that can arise from counting all sources of income, such as a grant to a third party meant to cover job training tuition. And, in other cases, Congress has explicitly excluded certain sources of income, such as special combat pay for military personnel, for public policy reasons. Nevertheless, the Agriculture Committees have endeavored for over 40 years to establish a SNAP benefit structure and calculation that is highly sensitive to family circumstances, including other forms of assistance.

Efforts to Coordinate SNAP With Other Programs

Part of our work at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is to work with states on improving the delivery of SNAP. We respond to states’ questions and requests for technical assistance on SNAP rules, best practices for business operations and ways to improve access to SNAP by eligible people. Because SNAP has a significant presence within the health and human services delivery system, states’ questions and concerns are not limited to SNAP policy and operations. They also want information and ideas about how to improve their overall operations and service delivery, including other programs such as Medicaid, child care, cash assistance through the Temporary for Needy Families (TANF) block grant and other programs. My colleagues and I have spent a great deal of time studying how SNAP interacts with other programs at the state and local level and the ways that states seek to coordinate SNAP with the array of services that they offer.

Many states have made progress over the last ten years in coordination or seamless service delivery across programs (as opposed to within a single program). Although, some states had coordinated policies on the books, too often the on-the-ground procedures needed to operationalize these policies did not exist. In addition, few if any states had an effective, data-based system for determining whether families were connected to the full range of programs for which they qualify.

Lack of cross-program coordination undermines states’ efforts to operate efficient systems. It also reduces overall support for families. Because they must navigate a complex and inefficient web of systems, families often are unable to secure the full package of benefits for which they are eligible. This undermines the safety net’s ability to support struggling families and seniors. For example, children are much likelier have better outcomes when they have access to health coverage and SNAP’s nutrition benefits for a comprehensive set of health supports.

Consider a family with low earnings that is eligible for children’s health coverage, SNAP, and child care. Despite the fact that these programs often serve the same families and require very similar enrollment information, under the worst case scenario a struggling family would have had to apply and renew benefits via three separate processes that are not very synchronized. Further, busy state workers in these three programs would spend time duplicating each other’s’ efforts. More typical, although still highly problematic, was a model where households would apply for several benefits through a single application process and then be required to keep separate workers representing the different programs appraised of their circumstances. Often, the household would also have to renew their eligibility through separate and redundant processes.

While these approaches to service delivery still exist, they are no longer the norm. States have worked very hard to break down the silos and redundant administrative systems among programs. They have been motivated by several reasons:

- As a result of the recent downturn, millions more families have lost income or are now out of work altogether. And many of these families have turned to their state governments for help through programs like unemployment insurance, SNAP, and health coverage. In addition, more people are eligible for health coverage through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) because of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). But states haven’t had more resources to deal with the increased demand. To the contrary, human services offices’ budgets and staff were cut as millions more people have walked through the doors. Despite these incredibly trying circumstances, states have managed to serve these new families in need, and several states have actually improved their service delivery through the downturn.

- Technology offers new opportunities. In a paper-bound system, it was often hard or administratively burdensome to share information across programs. Now many states have new options to work quickly. For example, today most states use document imaging systems as a means to save and file household verifications. They also offer call centers where clients can call and easily report a change in their situation and need for benefits. This technology can make it easier for participants and for state caseworkers to update multiple programs for new information about household circumstances.[6]

- Finding effective ways to leverage state resources to achieve more is in the states’ interest. When state agencies spend less staff time on processing eligibility, they can redeploy those resources to more important tasks like connecting families to work and supporting families who need more intensive supports.

- Making it easier for eligible low-income families and seniors to access all of the benefits for which they are eligible helps states’ struggling citizens. Making sure that eligible individuals can access the help that they need will help to ensure their financial stability. Many states believe that families can better spend their time looking for work (and staying in work) as well as address other family needs when they are not constantly at the local human services office standing in line and filling out redundant forms. As the body of evidence regarding the long term benefits of key health and human services programs emerge, it becomes even more compelling to connect eligible families and individuals to a package of these supports.

SNAP’s Role in Cross-Program Coordination Efforts

SNAP has played a major role in these efforts. Federal, state, and local policymakers who operate other programs appreciate many of SNAP’s features that I described earlier. They understand SNAP’s significant role in the broader health and human services world. Some of the key contexts that state and local leaders consider as they assess SNAP’s role in their broader systems:

- Individuals eligible for SNAP have relatively low income. As a result, they are often eligible for other federal and state benefits. For example, in virtually all cases, children who participate in SNAP will also be financially eligible for health coverage under Medicaid. And, for programs where states set the income eligibility rules such as child care subsidies and the low-income heating and energy assistance program (LIHEAP), SNAP participants typically have incomes well below the eligibility limits established by states. To be sure, SNAP participants will not necessarily qualify for these benefits. Some programs such as WIC or child care have additional non-financial eligibility criteria. In other cases, the programs do not receive sufficient funding to provide services or benefits to all those who qualify. Nevertheless, given that a large number of very low-income people participate in SNAP, it is a logical program to consider for basic coordination purposes.

- States co-administer SNAP with other major health and human services programs. According to USDA’s most recent State Options Report from 2012, more than 40 states co-administer SNAP and Medicaid.[7] Even more states co-administer SNAP and cash assistance under TANF. In addition, many of the agencies that administer SNAP also administer other human services programs such as child care, LIHEAP, job training programs as well as state and local services targeted at low-income people. This means that SNAP co-exists with other programs in state computer systems, within state policy manuals, in staff trainings, and on forms and notices. Finding efficient ways to coordinate the administration of these programs makes solid operational sense from a state and local perspective.

States seek new approaches to be more efficient and effective in their business operations and administrative costs. As the state human services agencies build computer systems, train staff, and build business operations to screen and enroll eligible low-income people into the array of programs that they offer, they look to solicit information from applicants once to assess their eligibility for the programs and services that the agency provides.

- SNAP rigorously assesses eligibility. As noted above, SNAP does a very thorough review of a household’s eligibility. SNAP state agencies are required to verify household circumstances through paper documentation and third-party data matches. Overall, the assessment required under federal law for SNAP far exceeds the requirements laid out in any other program. SNAP demands that states have relatively sophisticated means to process eligibility and verify a household’s circumstances. The quality and caliber of SNAP eligibility assessments is well understood within the health and human services arena. Not only can other programs rely upon the quality of SNAP’s eligibility findings, in many cases, using information that has been verified by SNAP will increase the integrity of the program importing the information.

Despite its strengths, SNAP isn’t a perfect partner. SNAP is a complex program with exacting federal standards. Because SNAP is a program of last resort and its benefits are fully financed by the federal government, the program rules target benefits to the neediest households with a very detailed current picture of their situation. Federal rules require quite a bit from households and states to ensure that the determination of eligibility is accurate and fair. As a result, SNAP’s complicated rules exceed what other programs require or desire. States do not typically wish to import all of SNAP’s rules into other programs. Instead, they find that they can import individual findings from SNAP, such as an income calculation, to other programs.

Examples of Cross-Program Coordination

One of our current efforts to support states’ efforts to improve program integration is through the Work Support Strategies (WSS) Initiative. The WSS Initiative is a foundation-supported effort led by the Center for Law and Social Policy and the Urban Institute. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities leads the technical assistance effort to states. The project is motivated by the value public benefit programs can provide to working families and the belief that the states and localities administering these programs can improve how eligible families access and retain these benefits. Under the project, core work support programs are defined as SNAP, health coverage, and child care.[8]

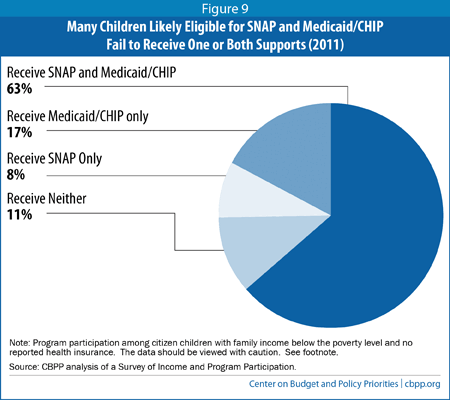

Also, families often miss out on programs that do, in fact, have sufficient funding to enroll all eligible people. For example, USDA estimates that SNAP served only 68 percent of people in eligible working families in 2011. The Urban Institute found that 4 million children who had no health insurance in 2011 were eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.[10] Data from national surveys confirm that children who are likely eligible for SNAP and Medicaid are not always enrolled in both. Virtually all U.S. citizen children in families whose annual income is at or below poverty and who do not report having health coverage should be eligible for both Medicaid/CHIP and SNAP. Figure 9[11] shows that nearly 40 percent of children likely to be eligible for both SNAP and health coverage are not receiving both programs.[12]

Our WSS grantee states (Colorado, Idaho, Illinois, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and South Carolina) have taken on the challenge of creating and implementing a plan to streamline, integrate, and improve the provision of work support benefits through their SNAP, Medicaid, and child care programs. Each state committed to the goal of increasing enrollment by eligible people in these core work support programs. While most states hope their efforts will also reduce the burden on caseworkers and administrative costs in these systems, all are motivated to improve the lives of the families they serve. These states are undertaking this work at an exciting time. The ACA changed the way that states must assess Medicaid eligibility, requiring states to rework their old eligibility rules. In addition, the ACA sets new standards for customer service and the means of doing eligibility determinations, which has required many states to upgrade their technology and offer new services such as online applications and phone service. As states implement these important changes and upgrades in Medicaid, they are actively looking for ways to leverage improvements in their overall systems.

Illinois Health and Human Services Secretary Michele Saddler outlined the state’s transformation of several key programs — like SNAP (food stamps), Medicaid, and child care — to help low-income families keep and maintain jobs in a hearing before the Ways and Means Committee last summer. Illinois is simplifying and aligning policies across programs and investing in new technology to make it easier for families to apply and easier for the state to verify their information. As Saddler explained:

“When I began, our benefit delivery system was broken. Families had to apply multiple times to get the assistance their family desperately needed. They had to take hours or even days off of work to sit in a local office to get help, potentially losing the very work we encourage. Our focus has been on finding and creating efficiencies in this system, seeking a better environment for customers and staff. A more efficient and accessible system leads to greater stability for families and ultimately saves the government future costs of benefits and administration.”[13]

Through both our everyday work with states and the WSS Initiative, we have observed many ways other programs can use SNAP to streamline their own administrative processes as well as improve the client experience.

- States and other program operators have implemented the federally mandated connections between SNAP and other programs. Congress has made the determination that, in some cases, enrollment in SNAP is sufficient evidence of financial eligibility for another program. For example, all children who participate in SNAP are deemed automatically eligible for the free school meals program. Pregnant and post-partum women and young children receiving SNAP are income eligible for the Special Supplemental Nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) although they must still meet the program’s criteria for nutrition risk to qualify. In these cases, Congress deemed that school meals and WIC must rely upon the SNAP income determination because it is so reliable. Moreover, households who apply for SNAP are self-identifying themselves as needing food assistance. Connecting these children and pregnant women to other programs that could help meet their nutrition needs is a sensible approach.

The new Work Opportunity Investment Act will allow individuals who participate in SNAP (among other programs) to be automatically determined to meet the income requirements for services. Other federal programs, such as Federal Financial Student Aid programs, allow applicants to skip certain portions of their needs assessments if the applicant or his or her family participate in SNAP. Program participation is considered a sufficient indication of financial need under the programs’ eligibility rules. - States and local governments use SNAP enrollment and information where they have the flexibility to set the rules. States can set the income eligibility guidelines for certain programs such as child care assistance through the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDF) and energy assistance through LIHEAP. If states establish income eligibility rules equal to or above the SNAP income eligibility limits, they can then use a household’s enrollment in SNAP as sufficient evidence that the family meets the program’s income eligibility limits.

Idaho, for example, recently raised its CCDF income eligibility to 130 percent of the federal poverty line, and indexed it to rise with inflation — thus, aligning the cutoff with SNAP and ensuring that the alignment would stay in force over time.[14] Programs like child care subsidies and LIHEAP are often run by local community action agencies that do not have the resources to invest in sophisticated computer eligibility systems with built-in third-party data checks. By using SNAP’s income determination, states ensure a high-quality, accurate assessment of need. Other entities that target their resources to low-income individuals or households also use SNAP enrollment as evidence of need. For example, school districts may elect to waive school fees for individuals who participate in SNAP.

It’s worth noting again that importing a SNAP income eligibility determination does not necessarily qualify an individual for other programs’ benefits. Often there will be other eligibility criteria and most human services programs do not have funding to meet demand.

States coordinate eligibility and enrollment processes with SNAP to eliminate redundant requests. Where states cannot or do not wish to align other programs’ income eligibility rules with SNAP (e.g., states often set much higher income eligibility guidelines for child care subsidies because they wish to provide child care subsidies to low- and moderate-income households), they may seek to coordinate or to align the processes by which they determine that applicants are eligible. Approximately one-third of states package SNAP online applications with at least four other programs. This means that people seeking more than one form of assistance only need to fill out a single application. Similarly, workers need to process only one application and the supporting verification.

Income verification is another area where the eligibility rules might differ but states could align the process. For example, one program might ask for the four most recent weeks of income while another asks for the last 30 days of income and a third asks for monthly income. Instead, a state might choose to set a different income eligibility limit for SNAP and another program but use the same income verification standards against which they measure eligibility. Because SNAP is often the most significant program in terms of size and paperwork and verification demands as well as quality control reviews, states often align other programs to its standards. New Hampshire and Oklahoma are two states that have standardized the types of verification they seek from families applying for both SNAP and child care.[15]

States can also use verified data in the SNAP record to support eligibility determination and redeterminations in other programs such as Medicaid or child care. This approach, often called an ex-parte review, allows families’ benefits in other programs to be proactively renewed using current information from another program such as SNAP. The agency looks at other systems before seeking any information from the client at renewal. If a child care worker, for example, checked if a family was enrolled in SNAP, they could use SNAP data to renew income eligibility for child care benefits and would need to gather only the additional relevant information on work status or other unique child care eligibility elements.[16]

To be sure, perfect alignment is rarely achieved and often is not desirable. First, SNAP’s rules do differ from other programs’. The SNAP household definition is based on which group of individuals living together purchase and prepare food together. This understandably differs from which group of individuals could be expected to contribute to the health care costs of others. Moreover, SNAP’s eligibility standards are rigorous. Households are required to provide extensive documentation of their circumstances, participate in an eligibility interview, report significant change in their circumstances as they arise, and have their eligibility reassessed on a regular basis. Other programs do not have the necessary administrative funding to pursue such an approach, nor would it be appropriate for them to do so given their structure and design.

As states work to better coordinate their systems, they are discovering that there is often far more flexibility in federal programs to align and coordinate, or cross-leverage, information than they thought. Often disconnects are the result of their own making or a lack of understanding of the flexibility given to them by the federal government. Other times, differences between programs are by design and originate from the programs’ different goals, as described above in the household definition example. And, there are times when states discover differences between programs that raise reasonably questions. For example, several states have asked if they can use employer records to verify household income via states’ unemployment records for households with stable circumstances. Medicaid allows and encourages states to use third party data matches to verify income even if the information is a little dated. SNAP historically has required current information even from households with very stable employment arrangements. In such a case, the federal government will permit waivers from federal SNAP requirements to test whether allowing SNAP to use other programs’ rules is appropriate and cost effective. And USDA and HHS are soliciting additional ideas from states where sensible alignment opportunities exist.

Looking Ahead: SNAP’s Relationship to Other Assistance Programs

I appreciate the subcommittee’s effort to delve into the relationship between SNAP and other federal assistance programs. SNAP plays a major role in the broader arena of health and human services programs. It is both responsive to and has a significant impact on many programs outside of the Committee’s jurisdiction. I hope that my testimony has given you some sense of how your work influences other programs through SNAP. The state agencies and SNAP caseworkers that operate and implement SNAP must think about the program in the context of the health and human services systems they are running. It’s helpful to consider SNAP’s environment and program operators’ perspectives as we strive to improve the program and further its positive impact on struggling individuals and families.

There can be a tension between remaining true to SNAP’s goals of addressing food insecurity and hunger and harmonizing and coordinating SNAP policies with other federal assistance programs. If SNAP aligned perfectly with other programs, it would no longer be SNAP. Many of its unique features are by design and contribute to its success. As you consider options to improve coordination, it is important that those proposals not undermine SNAP’s strengths as a food assistance program targeted to individuals and families with the least ability to purchase food. Proposals to sweep away some of SNAP’s key features or that would shift benefits away from food assistance to other purposes run afoul of the program’s goals and proven success.

Section 4016 of the 2014 Farm Bill is an example of a positive policy change to help harmonize SNAP with other programs. That provision requires that USDA work with other federal agencies to create data exchange standards consistent with other federal assistance programs. This will facilitate the ability of programs (and federal and state governments) to share data across programs. Such standardization is expected to help improve program integrity and to improve our ability to assess program performance.

USDA can do more to assist states’ efforts to administer SNAP as part of the larger health and human services system. First and foremost, USDA’s oversight and policy development would be strengthened if its staff developed more expertise in other federal assistance programs. When SNAP policy is inconsistent with other major programs such as Medicaid, it would be helpful for USDA to be aware of those differences and to flag them for states. (The same holds true for HHS.) State and local governments, even individual caseworkers, ought not to be left on their own to disentangle differing federal rules and regulations. It seems reasonable for the federal agencies to navigate what we ask their state counterparts to manage. That having been said, USDA has taken steps to engage SNAP agencies in a conversation about how the recent changes in Medicaid could be affecting SNAP operations at the local level. They can do more here, and I encourage them to do so.

As states undertake innovative and effective cross-program coordination efforts, we ought to seek to share those best practices across states. The Work Support Strategies Initiative offers such an opportunity and we plan to do more dissemination about the project in the coming year.

I also believe that the federal government could do more to assess how well federal and state agencies are doing with respect to connecting eligible low-income people to the package of key supports for poor children, working families, and seniors and people with disabilities. Low-income people will likely fare better if they can count on the help of SNAP, health coverage, and other work supports — programs that we know work and that improve the long-term outcomes of those who receive them. Policymakers need information about how well states connect eligible individuals to these programs as a whole. We can learn from states that do well and identify barriers in federal rules or local practice that may impede states from comprehensively addressing their residents’ needs.

Finally, I did not spend time in my testimony on the interaction between SNAP and the major federal entitlements for seniors and people with disabilities — Social Security and Medicare. Current SNAP law instructs the Social Security Administration (SSA) to inform Social Security and SSI applicants and participants about SNAP benefits and streamline the SNAP application process for them. USDA reimburses SSA for these activities. As low-income senior citizens have the lowest SNAP participation rates of any demographic group, but very high Social Security and Medicare participation rates. I believe that more could be done to assist poor eligible seniors to enroll in SNAP at SSA offices. A future oversight hearing or more work by USDA to explore how this process could be improved could go a long way to improving the food security of low-income senior citizens and people with disabilities.

Conclusion

SNAP is an efficient and effective program. It alleviates hunger and poverty and has positive impacts on the long-term outcomes of those who receive its benefits.

SNAP is highly targeted, making it very sensitive to the other benefits that families receive. SNAP either counts their income or recognizes households that receive benefits from other programs by generally providing less assistance to those families than families who do not receive other forms of assistance.

And, SNAP has exacting standards with respect to eligibility and administrative requirements. This makes it a good fit for states to looking to use its findings for other programs. Such integration increases efficiency by reducing administrative costs and can help eligible families receive the help that they need with fewer transaction costs.

End Notes

[1] My testimony draws upon the work of my colleagues at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, particularly Dorothy Rosenbaum.

[2] Congressional Budget Office, “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program,” April 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/04-19-SNAP.pdf.

[3] Hilary W. Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18535, 2012, www.nber.org/papers/w18535.

[4] See the fiscal year 2013 error rates: http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/quality-control.

[5] For both SNAP and taxes the figures represent gross estimates (i.e., before SNAP households repay overpayments, taxpayers make voluntary late payments, or consideration of IRS enforcement activities.) The net costs are somewhat lower. See: Internal Revenue Service, “Tax Gap for Tax Year 2006, Overview,” January 6, 2012, http://www.irs.gov/pub/newsroom/overview_tax_gap_2006.pdf.

[6] For more information on how states are leveraging new technology with respect to health and human services programs, including SNAP, see “GAINING GROUND: A Guide to Facilitating Technology Innovation in Human Services,” by Freedman Consulting, http://tfreedmanconsulting.com/documents/GainingGround_FINAL.pdf.

[7] See program integration table on page 23 http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/10-State_Options.pdf.

[8] For more information about WSS, see: http://www.urban.org/worksupport/.

[9]“Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and Receipt for Fiscal Year 2009,” U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, August 2012, http://aspe.hhs.gov/hsp/12/childcareeligibility/ib.cfm.

[10] “Medicaid/CHIP Participation Rates Among Children: An Update,” Urban Institute, September 2013, http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412901-%20Medicaid-CHIP-Participation-Rates-Among-Children-An-Update.pdf.

[11] The data for this analysis are from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for calendar year 2011. We limited the analysis to U.S. citizen children with incomes below the federal poverty level because these individuals are very likely to be eligible for both Medicaid and SNAP. The data should be interpreted with caution, as the SIPP significantly undercounts participation in Medicaid and SNAP. In 2009 the number of children reported in the SIPP as receiving SNAP is only about 75 percent of the number of children thought to have actually received SNAP based on SNAP administrative data. USDA finds that SNAP reaches about 85 percent of eligible children, rather than the 67 percent identified in this SIPP analysis. Similarly, the SIPP does not include about a third to 40 percent of the children who receive health coverage through Medicaid or CHIP.

[12] A recent Urban Institute study based on a different national survey (the American Community Survey) found that in 2008 about 15 percent of children without health insurance coverage but eligible for Medicaid or CHIP were in households that received SNAP. This difference demonstrates that while there appear to be significant numbers of families that do not receive all the benefits for which they qualify, national survey data have significant limitations which may make it difficult to obtain accurate figures. See Genevieve M. Kenney, Victoria Lynch, Allison Cook, and Samantha Phong, “Who And Where Are The Children Yet To Enroll In Medicaid And The Children’s Health Insurance Program?” Health Affairs, October 2010, vol. 29 no. 10, 1920-1929.

[13] Secretary Michelle Saddler’s testimony before the House Committee on Ways and Means Subcommittee on Human Resources, July 31, 2013, see: http://waysandmeans.house.gov/uploadedfiles/michelle_saddler_testimony_hr073113.pdf

[14] “Confronting the Child Care Eligibility Maze: Simplifying and Aligning with Other Work Supports”, by

Gina Adams and Hannah Matthews, December 2013, p. 31, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412971-confronting-the-child-care.pdf.

[15] Ibid, p. 38.

[16] Ibid, p. 40.

More from the Authors