- Home

- The Long-Term Fiscal Outlook Is Bleak

The Long-Term Fiscal Outlook Is Bleak

Restoring Fiscal Sustainability Will Require Major Changes to Programs, Revenues, and the Nation’s Health Care System

Richard Kogan, Matt Fiedler, Aviva Aron-Dine, and James R. Horney

Summary

In 2006, the federal government ran a deficit of $248 billion, or about 2 percent of the economy. Deficits are projected to average about 2 percent of GDP over the next ten years, assuming the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are extended. After that, the fiscal situation is expected to deteriorate markedly.

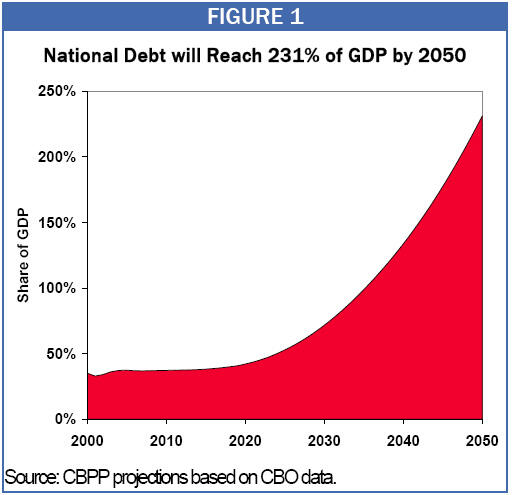

In this analysis, we present new projections for the federal budget through 2050. These projections, based on data and estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, are deeply disquieting. They show that the nation’s budget policies are unsustainable, with deficits and debt growing to unprecedented and dangerous levels if policy changes are not made.

The new projections also shed light on the sources of these problems and on the types of changes that would be needed to address them responsibly. Our principal findings are the following:

-

The main sources of rising expenditures are rising health care costs (throughout the U.S. health care system) and demographic changes, which together will drive up spending for the “big three” domestic programs — Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security.

-

A solution to the long-term fiscal problem will require not only difficult choices to reduce programs and increase revenues, but also fundamental changes tothe entire U.S. health care system.

-

Tax policy decisions Congress will face in coming years will have a substantial impact on the magnitude of the long-term problem. If Congress lets recent tax cuts expire by 2010 as scheduled or extends them (in whole or in part) but offsets the costs, the size of the problem through 2050 will shrink by 60 percent. This is because the resulting deficit reduction, begun in the next few years, would have an increasing impact on federal interest payments with each passing year and would thereby reduce long-term deficits even more over time. Even so, the budget would remain on an unsustainable fiscal path.

Federal programs other than Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security — including entitlement programs other than the “big three” — are not expected to grow rapidly; in fact, these programs will shrink as a share of the economy and thus will consume a smaller share of the nation’s resources in 2050 than they do today.

Current Budget Policies are Unsustainable

The nation’s budget policies are unsustainable. Our projections show that if current budget policies are continued (e.g., if current laws governing Medicare, Social Security, and other programs remain unchanged, the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are made permanent, and relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax is continued), deficits will reach about 20 percent of the Gross Domestic Product by 2050, and the national debt will climb to 231 percent of GDP by that year, or more than twice the size of the U.S. economy. Debt-to-GDP ratios in this range are unprecedented in the United States, even during major wars.

Debt at this level would seriously damage the economy. It also would place severe strains on the federal budget. For example, by 2050, simply paying interest on the national debt would consume more than half of annual projected federal revenues.

Another way of measuring the size of the problem is to examine the magnitude of the long-term fiscal gap. The fiscal gap represents the amount of program reductions or revenue increases needed over the next four decades to ensure that the debt, measured as a share of the economy, is no larger in 2050 than it is today. Under our projections, the fiscal gap equals 3.2 percent of projected GDP through 2050. Hence, stabilizing the nation’s finances through 2050 would require annual tax increases or budget cuts equal to 3.2 percent of GDP, starting with tax increases and budget cuts totaling $461 billion in 2008 alone. ($461 billion equals 3.2 percent of projected GDP for 2008.)

As these figures suggest, eliminating a fiscal gap equal to 3.2 percent of GDP would be very difficult. Even so, some readers may wonder how it is that the nation could reduce the debt in 2050 from 231 percent of GDP to its current level of 37 percent of GDP simply by making annual changes equal to 3.2 percent of GDP. This is possible if the changes startimmediately. If we began to institute these revenue increases or program reductions this year, we would begin running surpluses rather than deficits, which would decrease rather than increase the national debt. The reductions in the debt, in turn, would reduce interest costs in every year through 2050, bringing the “miracle of compound interest” to bear on the budget problem. Compound interest also can work against us, however: if little or no deficit reduction is enacted in the near future, substantially larger deficit reduction will be required later.

Health Care Costs and Demographic Changes — Not Entitlements Generally — Account for Rising Expenditures

The main sources of rising expenditures are rising costs throughout the U.S. health care system and demographic changes, with health care costs playing the larger role. Together, these two forces will cause the “big three” domestic programs — Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid — to grow considerably faster than the economy. Collectively, these three programs are projected to grow by slightly more than 13 percent of GDP between now and 2050.

All other programs, including all domestic programs other than the “big three,” are projected to grow more slowly than the economy in coming decades and consequently do not contribute to the projected rise in deficits and debt. Of particular note, entitlement programs outside of the “big three” are projected to grow more slowly than the economy. Common pronouncements that the nation’s fiscal problems result from a general “entitlement crisis” are thus mistaken.

Tax Policy Choices Will Have a Major Impact on the Long-Term Problem

Tax policy decisions Congress will make over the next few years have significant implications for the size of the long-term problem. As explained above, our projections show a fiscal gap of 3.2 percent of GDP. This means that enacting annual revenue increases or program reductions equal to 3.2 percent of GDP would ensure that debt in 2050 was no higher than it is today as a share of the economy. Since allowing recent tax cuts to expire as scheduled would increase revenues by about 2 percent of GDP each year, it would reduce the fiscal gap by three-fifths, shrinking it from 3.2 percent of GDP through 2050 to 1.3 percent. Stated differently, making the recent tax cuts permanent without paying for them would more than double the fiscal gap through 2050, relative to what it would otherwise be.

These tax policy decisions will have such a profound effect on the long-term fiscal outlook because they will be made soon. Declining to extend the tax cuts, or offsetting the cost of doing so, would quickly begin to reduce deficits and debt, and these changes would compound over time.

Still, allowing the tax cuts to expire falls far short of what is needed to place the nation on a sustainable fiscal path. Even if the tax cuts expired or were fully offset, debt in 2050 would stand at more than 100 percent of GDP. Moreover, after 2050, debt would continue to rise. Measured over a period that extended beyond 2050, allowing the tax cuts to expire would reduce the size of the problem by a smaller, but still substantial, percentage.

Tough Changes, Including Health Care Reform, Will be Required

In light of this budget outlook, very tough choices will have to be made. As explained above, eliminating the fiscal gap through 2050 would require tax increases or program cuts totaling 3.2 percent of GDP annually through 2050, if the process started immediately. It would be politically implausible (as well as inadvisable on policy grounds) to try to eliminate the fiscal gap solely by raising taxes or solely by cutting programs. Doing so would require the equivalent of an immediate and permanent 18 percent increase in tax revenues or an immediate and permanent 15 percent reduction in all programs, including Social Security, Medicare, defense and anti-terrorism activities, education, veterans’ benefits, law enforcement, border security, environmental protection, and assistance to the poor. Thus, it is crucial that both sides of the budget — revenues and expenditures — be on the table when serious conversations about deficit reduction begin.

An important finding of our projections, however, is that responsibly addressing the nation’s budget problems will require more than making changes to both sides of the budget. Addressing the nation’s fiscal problem also will require fundamental reforms to the U.S. health care system as a whole. As discussed below, health care costs are the single largest contributor to the long-run budget problem, and cost growth in Medicare and Medicaid tends to mirror — and is driven to a very large extent by — cost growth in the health care system as a whole, including private-sector health care. Indeed, for the past 30 years, the average annual rate of increase in Medicare costs per beneficiary has been very close to the average rate of increase in health care costs per beneficiary system-wide.

Consequently, trying to slow public-sector health care cost growth appreciably without addressing private-sector health care cost growth would require draconian cuts in Medicare and Medicaid that would have severe effects on the poor, the elderly, and those with serious disabilities. Moreover, such cuts would, to some extent, simply shift public-sector health care costs onto the private sector, for instance by forcing health care providers to give greater amounts of uncompensated care, the costs of which would be passed on to private-sector employers and patients. For these reasons, any reforms aimed at reducing the rate of growth of Medicare and Medicaid must be part of a package of reforms designed to slow cost growth throughout the health care system, a point that Comptroller General David Walker has repeatedly made.

It also should be understood that even with major reforms, it is likely to prove virtually impossible to hold health care expenditures in either the public or the private sector to their current levels as a share of the economy. While the U.S. health care system contains significant inefficiencies that raise its costs, the rate of growth in health care costs is driven largely by medical advances that tend to improve health and lengthen lifespans but that also increase costs. It is inconceivable that Americans will not want to avail themselves of the medical breakthroughs that will occur in the years and decades ahead, even if they entail significant costs. Furthermore, ongoing economic growth will raise incomes in coming decades, and it would not be unreasonable for Americans to elect to invest a substantial share of that increase in securing better health and longer lives. The challenge therefore is to pursue major reforms that eliminate inefficiencies in the health care system and restrain costs in the system to the greatest extent possible without unduly constraining medical progress. Of course, if, as seems likely, Americans conclude that better health and longer lives merit a somewhat larger share of their income in the future, it will be necessary to pay for these added costs, rather than simply pile up ever-mounting levels of debt.

In sum, solving the nation’s long-term budget problems will require that political leaders enact both program reductions and revenue increases and, perhaps most difficult of all, substantial, system-wide health-care reforms.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise