The Importance Of Social Security To The Hispanic Community

End Notes

[1] Fernando Torres-Gil is Director of the UCLA Center for Policy Research on Aging and Acting Dean of the UCLA School of Public Affairs. Robert Greenstein is Executive Director, and David Kamin is a Research Assistant, at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[2] Recent CBPP analyses describe how rate-of-return comparisons are often used improperly by advocates of private accounts who claim that the rate of return on private accounts is higher than under the traditional Social Security system. These claims rest on “apples-to-oranges” comparisons that do not take into account all of the benefits provided by Social Security and also the additional costs entailed in replacing part of Social Security with private accounts. (For additional details, see pp. 8-11.)

Rate-of-return comparisons can be informative, when done on an “apples-to-apples” basis. Here, we are comparing Hispanics’ rate of return on contributions to the Social Security system to the rate of return that other populations receive on contributions to Social Security. This is a valid comparison, done on a consistent basis, that helps to illustrate who benefits more from the Social Security system.

[3] Jeffrey Liebman, “Redistribution in the Current U.S. Social Security System,” in The Distributional Effects of Social Security and Social Security Reform, Martin Feldstein and Jeffrey Liebman, eds., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 31.

[4] In Congressional testimony several years ago, the National Council of La Raza (NCLR) reached many of the same conclusions as this analysis. NCLR found that Hispanics receive higher rates of return on their contributions to Social Security than other workers, and NCLR criticized proposals that would replace Social Security with private accounts as being detrimental to the Hispanic community. National Council of La Raza, “Social Security Reform: Issues for Hispanic Americans,” Submitted to the Committee on Ways and Means, Subcommittee on Social Security, Presented by Eric Rodriguez, Senior Policy Analyst, on behalf of Sonia M. Perez, Senior Vice President, February 10, 1999, available at http://www.nclr.org/content/publications/download/29396.

[5] Fernando Torres-Gil, Robert Greenstein, and David Kamin, “Hispanics and Social Security Reform: The Implications of Reform Proposals,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 28, 2005.

[6] Social Security Administration (SSA), “Social Security is Important to Hispanics,” September 2004, available at http://www.ssa.gov/pressoffice/factsheets/hispanics.htm.

[7] Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Social Security and Minorities: Earnings, Disability Incidence, and Mortality are Key Factors that Influence Taxes Paid and Benefits Received,” April 2003, p. 11, available at https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/d03387.pdf

[8] GAO, “Social Security and Minorities,” p. 12.

[9] SSA, Annual Statistical Supplement, 2004, Table 5.A1.4, available at http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ statcomps/supplement/.

[10] Brady E. Hamilton, Joyce A. Martin, and Paul D. Sutton, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Births: Preliminary Data for 2003,” National Vital Statistics Reports, November 23, 2004, p. 2, available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr53/nvsr53_09.pdf. In recent years, the Hispanic fertility rate has declined. From 1990 to 2003, the Hispanic fertility rate fell from 3.0 children per woman to 2.8 children per woman, even while the national fertility rate held steady. Nonetheless, it is likely that Hispanics will continue to have higher fertility rates than the rest of the population for many decades to come. In fact the Census Bureau, in its long-term population projections, assumes that fertility rates for the Hispanic population, while falling, will remain above the fertility rate for the rest of the population through 2100. Thus, for the foreseeable future, Hispanics are likely to continue to gain disproportionately from Social Security’s benefits for children.

[11] SSA, “Social Security is Important to Hispanics.”

[12] Several researchers have raised questions as to whether Hispanics’ longer-than-average life expectancies are real or are a product of measurement error. For instance, see Alberto Palloni and Elizabeth Arias, “Paradox Lost: Explaining the Hispanic Adult Mortality Advantage,” Demography, vol. 41, no. 3, August 2003, pp. 385-415. Even if Hispanics did not have longer-than-average life expectancies, they would receive well-above-average rates of return on their contributions to the Social Security system because they exhibit all of the other characteristics described here. This is confirmed by the studies described in the next section of this paper, which do not assume that Hispanics have longer-than-average life expectancies and still find that Hispanics receive a higher rate of return on the taxes they pay into the Social Security system than does the rest of the population.

[13] The results of these studies, which use Social Security records combined with other data sources, exclude those undocumented workers who, because of their illegal work status, do not receive benefits based on their contributions to Social Security. Despite their illegal work status, undocumented immigrants frequently do pay taxes into the Social Security system under false or non-work status Social Security numbers, and many of these undocumented immigrants will never collect Social Security benefits based on these taxes paid while working illegally. (Only those who eventually become legal workers may collect benefits.) The studies cited here do not consider the negative rates of return for these undocumented immigrants on their payments to Social Security.

[14] One paper was written by Liebman alone; Liebman co-authored the other paper with Feldstein. In both papers, the authors used a sample of Social Security records and other data sources to determine the economic and demographic characteristics of Social Security participants. To better capture the rate of return on Social Security over the long term, they assumed that covered workers would face a payroll tax rate six percentage points higher than under current law. This would be sufficient to cover the cost of Social Security benefits modeled in the paper on a cash basis in 2075.

Under these assumptions, Liebman, in one paper, found that the annual rate of return on Hispanics’ contributions to the Social Security system is 2.46 percent above inflation, whereas the rate of return for the population as a whole is 1.53 percent above inflation. In a second paper, Liebman and Feldstein reported that the annual rate of return on Hispanics’ contributions to the Social Security system is 1.81 percent above inflation, whereas the rate of return for the population as a whole is 1.35 percent above inflation. By the first estimate, Hispanics’ rate of return on Social Security is about 60 percent above the rate of return for the rest of the population. By the second estimate, Hispanics’ rate of return is about 35 percent above the rate of return for the rest of the population.

See Jeffrey B. Liebman, “Redistribution in the Current U.S. Social Security System,” in The Distributional Effects of Social Security and Social Security Reform, Martin Feldstein and Jeffrey B. Liebman, eds., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002. Also, Martin Felstein and Jeffrey B. Liebman, “The Distributional Effects of an Investment-Based Social Security System,” in The Distributional Effects of Social Security and Social Security Reform, Martin Feldstein and Jeffrey B. Liebman, eds., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

[15] Lee Cohen, C. Eugene Steurele, and Adam Carasso, “The Effect of Disability Insurance on Redistribution Within Social Security By Gender, Education, Race, and Income,” June 2002, available at http://www.bc.edu/centers/crr/papers/Fourth/cp_02_3_steuercohencaras.pdf .

[16] GAO, “Social Security and Minorities.”

[17] GAO, Testimony before the Social Security Subcommittee, House Committee on Ways and Means, February 10, 1999, available at http://www.gao.gov/archive/1999/he99060t.pdf.

[18] Memorandum from Stephen C. Goss, Deputy Chief Actuary, to Harry C. Ballantyne, Chief Actuary, “Comments on Heritage Rates of Return for Hispanic Americans,” Social Security Administration, April 2, 1998.

[19] SSA, “Social Security and Hispanic Americans: Some Basic Facts,” July 1998.

[20] For additional analysis of the “rate of return myth,” see Jason Furman, “https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-2-05socsec.pdf” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2, 2005.

[21] Felstein and Liebman, “The Distributional Effects of an Investment-Based Social Security System.”

[22] For a detailed critique of the Feldstein and Liebman analysis, see Peter Orszag and John Orszag, “https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/4-26-00socsec.pdf,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 26, 2000. For additional analysis of the problems with comparing the rate of return on private accounts to the rate of return on Social Security, see Jason Furman, “

” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2, 2005.[23] Advisory Council on Social Security, Report of the 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security: Findings and Recommendations, January 1997.

[24] William W. Beach and Gareth G. Davis, “Social Security’s Rate of Return for Hispanic Americans,” Heritage Foundation, March 27, 1998, available at http://www.heritage.org/Research/SocialSecurity/CDA98-02.cfm.

[25] See Goss, “Comments on Heritage Rates of Return for Hispanic Americans.” Also, Memorandum from Steve Goss, Deputy Chief Actuary, “Problems with ‘Social Security’s Rate of Return’: A Report of the Heritage Center for Data Analysis,” February 4, 1998.

[26] Robert J. Myers, “A Glaring Error: Why One Study of Social Security Misstates Returns,” The Actuary, September 1998, p. 5, available at http://library.soa.org/library/actuary/1990-99/ACT9809.pdf.

[27] For a more detailed critique of the Heritage Foundation’s findings, see Kilolo Kijakazi, “https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/10-5-98socsec.pdf,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 8, 1998. This report draws from that analysis.

[28] Goss, “Problems with ‘Social Security’s Rate of Return.’”

[29] Goss, “Comments on Heritage Rates of Return for Hispanic Americans.”

[30] Richard Fry, Rakesh Kochhar, Jeffrey Passel, and Roberto Suro, “Hispanics and the Social Security Debate,” Pew Hispanic Center, March 16, 2005, p. 10, available at http://pewhispanic.org/files/reports/43.pdf.

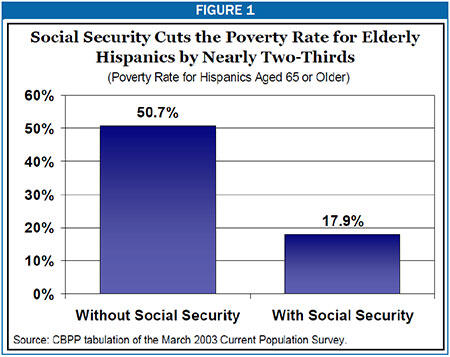

[31] In determining poverty status, these calculations use family disposable income (that is, after-tax cash income plus food, housing, and energy assistance). This approach results in lower estimates of poverty than the official Census Bureau poverty data, which rely on pre-tax income and do not include non-cash benefits. (Under the Census Bureau’s official poverty measure, Social Security has nearly the same anti-poverty effect as reported here. Based on the official poverty measure, Social Security reduced the poverty rate among elderly Hispanics by 31 percentage points in 2002, from 52.1 percent to 21.4 percent.) For more details on the methodology, see the “Technical Note” in Arloc Sherman and Isaac Shapiro, “https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-24-05socsec.pdf,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 24, 2005.

[32] It should be noted that a smaller percentage of elderly Hispanics receive Social Security than of other retirees. The lower participation rates are a result of a number of factors. Undocumented workers, many of whom are Hispanic, also are ineligible for benefits. In addition, as noted, Social Security’s eligibility threshold, which requires ten years of covered work, can adversely affect Hispanic workers. Undocumented workers — many of whom are Hispanic — also are ineligible for benefits.

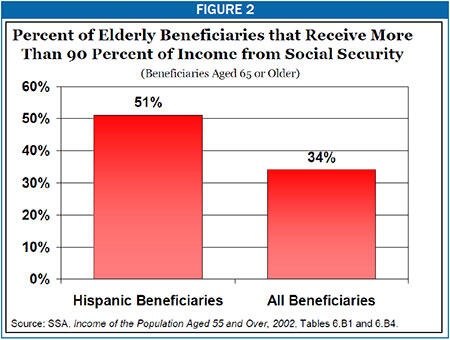

Despite these lower participation rates, the elderly Hispanic population — including non-beneficiaries — receives a greater share of its income, on average, from Social Security than the population as a whole (see table 2). This is because those Hispanic retirees who do receive Social Security checks rely especially heavily on that income to support their retirement.

[33] Social Security Administration, “Income of the Population Aged 55 or Older, 2002,” March 2005, Tables 7.1 and 7.4, available at http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/income_pop55/2002/.

[34] Ibid., Tables 6.B1 and 6.B4.

[35] Fry, et. al., “Hispanics and the Social Security Debate,” p. 12.

[36] Wealth figures expressed in 2003 dollars. Ibid., p. 17.

[37] Craig Copeland, “Employment-Based Retirement Plan Participation: Geographic Differences and Trends,” Employee Benefit Research Institute Issue Brief, October 2004, available at http://www.ebri.org/ibpdfs/1004ib.pdf.

[38] “Hispanics and Social Security: The Implications of Reform Proposals,” June 28, 2005.