- Home

- Tax Reconciliation Agreement Distorted B...

Tax Reconciliation Agreement Distorted by Obsession with Capital Gains and Dividend Tax Cuts

Middle-Income Households To Receive Tax Cuts Averaging Only $20

Summary

House and Senate negotiators announced an agreement yesterday on a tax-cut reconciliation bill that would reduce revenues by $70 billion between 2006 and 2010, according to Joint Committee on Taxation estimates. Although nearly half of this cost reflects a one-year extension of relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax, it is the two-year extension of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts that fundamentally shaped the final agreement. Even though the capital gains and dividend tax cuts are not slated to expire until the end of 2008, the Administration and Congressional leaders went to great lengths to ensure that a two-year extension through 2010 is part of the final package.

The end result is a conference agreement that:

- circumvents the reconciliation cost limits by leaving out popular tax-cut provisions with the full intention of enacting them in a subsequent bill, thereby increasing the total budgetary cost and the amount by which the deficit will be increased;

- relies in large part on budget gimmicks and timing shifts to create the appearance that it is complying with a key Senate budget rule that bars the reconciliation bill from increasing the deficit in any year after 2010; and

- provides an overwhelming share of its tax-cut benefits to those at very high income levels.

Tax Cuts Left Out. The conference agreement omits more than a dozen other tax-cut provisions that were in both the House- and Senate-passed reconciliation bills, such as the extension of the research and experimentation tax credit and the higher-education tuition deduction. (See Table 2 on page 5 for a complete list of these omitted provisions.) A one-year extension of these provisions costs about $20 billion.

Unlike the capital gains and dividend tax cuts, these provisions all have already expired or will expire at the end of 2006, meaning that failure to extend them this year would have immediate consequences. Congressional leaders could not include these expiring “extenders,” however, and also pack a two-year extension of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts within the $70 billion cost limit for the tax reconciliation bill. They concluded that they needed the protections against a filibuster that a reconciliation bill provides in order to pass the capital gains and dividend tax cut extension, but do not need these protections to pass the continuation of the other expiring tax provisions. Accordingly, their plan is to move these other tax cuts in coming weeks or months in one or more other tax bills outside of the reconciliation process, thereby adding still more to budget deficits.

Gimmicks to Evade Senate Rules. The reconciliation bill employs budget gimmicks and timing shifts to help offset the $30 billion cost that the Joint Committee on Taxation says will result in years after 2010 from extending the capital gains and dividend tax cuts through2010. Senate rules bar a reconciliation bill that increases deficits in any year after the end of the budget period that the reconciliation bill covers; for this bill, that period is 2006-2010. It takes 60 votes to waive this rule.

| Table 1: |

| The Agreement Relies on Provisions that Shift Corporate Tax Payments: |

| From FY 2007 to FY 2006 |

| From FY 2010 to FY 2011 |

| From FY 2011 to FY 2012 |

| From FY 2013 to FY 2012 |

| From FY 2014 to FY 2013 |

The agreement relies heavily on timing shifts. For instance, the measure includes multiple provisions to shift corporate tax payments between years, particularly to mask revenue losses that occur after 2010 (see Table 1). Another timing shift involves a temporary extension of a tax break for small businesses; the provision loses revenue while it is in effect, but raises revenue after it has expired. The bill slates this provision to expire at the end of 2009. There is every reason to believe, however, that this popular tax break will not be allowed to expire and will become one of the group of business tax cuts, known as “extenders,” that always are extended when they are scheduled to expire. As a consequence, the revenues that the official cost estimate assumes will be raised in 2011-2015 as a result of the expiration of the provision likely will never materialize. (See the box below for a longer discussion.)

Most troubling, the bill includes a substantial tax cut for affluent households disguised as an offset — that is, it attempts to use one tax cut to pay for another tax cut. This provision, which will allow high-income individuals to convert regular IRAs to Roth IRAs, will raise revenue initially but lose significantly larger amounts of revenue in later years, according to analyses by the Joint Tax Committee, the Congressional Research Service, and the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center. The conferees have used this temporary increase in revenue to help “offset” the cost of the capital gains and dividend tax cut in 2011-2013, but the eventual revenue losses, which will start in 2014, will continue to grow in the years after 2015, when the official cost estimate ends. After a few years, these revenue losses will begin to outstrip the revenue gains from the other offsets contained in the conference agreement (which are modest). As a result, the agreement will increase long-term deficits, violating the Senate rule designed to prevent such an outcome.

In pursuing this gimmick, the conferees are exploiting the fact that the official Joint Tax Committee cost estimate on the conference agreement does not cover years after 2015, and thus does not show years in which the bill will increasethe deficit. This enables Congressional leaders — including Senate Budget Committee Chairman Judd Gregg — to claim there is no evidence that the agreement violates the Senate rule. Since the Parliamentarian traditionally defers to the Senate Budget Committee Chairman on matters involving cost estimates, the gimmick is expected to succeed.

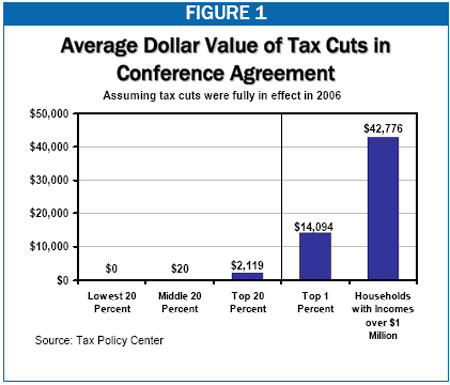

Benefits Skewed to the Well-Off. The final package offers virtually no benefits to low- and moderate-income households while showering high-income households with munificent tax cuts. Preliminary estimates by the Tax Policy Center of the major provisions in the conference agreement show that middle-income households will receive an average tax cut of just $20 (about enough to purchase six gallons of gasoline), while households with incomes over $1 million will see tax cuts averaging $43,000. [1] For the top 0.1 percent of households, whose incomes exceed $1.6 million, the tax cuts will average $84,000.

Overall, 55 percent of the tax-cut benefits will flow to the 3 percent of households with incomes above $200,000, and 22 percent of the benefits will go to the 0.2 percent of households with income over $1 million. In contrast, the 20 percent of households with incomes in the middle of the income spectrum will receive less than one percent of the benefits.

That the benefits are so skewed to those at the top of the income spectrum reflects, in large part, the impact of the capital gains and dividend tax cuts that Congressional leaders went to such lengths to protect. Nearly half (45 percent) of the benefits of extending these two tax cuts will go to households with incomes over $1 million.

End Notes

[1] The various provisions in the final reconciliation bill will be in effect during different years. To estimate the distributional effects of the bill as a whole, the Tax Policy Center employed the simplifying assumption that all of the provisions would be in effect in 2006. Our distributional estimates have been updated to reflect the Tax Policy Center's most recent distributional estimates.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise