- Home

- Still Risky Business: South Carolina’s R...

Still Risky Business: South Carolina’s Revised Medicaid Waiver Proposal

On November 16, 2005, South Carolina requested federal permission to make radical changes in its Medicaid program. The request, which took the form of a proposed waiver of federal Medicaid rules, would affect more than 700,000 low-income South Carolina children, parents, and people with disabilities.[1] The November proposal revises an earlier waiver request that the state submitted to the federal government in June.[2]

The new proposal addresses some of the problems with the earlier submission. It exempts children from its proposed changes in the Medicaid benefit package and from the increased cost-sharing requirements it contains. Nevertheless, the proposal continues to present significant risks for beneficiaries, the state, and health care providers.

The proposed changes in the way that benefits would be provided would significantly increase administrative costs for the state, while decreasing the amount of funds available to pay for health care benefits. The state would have to hire a multitude of vendors to operate the program, and beneficiaries would have to navigate a complicated new system. Managed care plans would be protected from risk (through reinsurance), while beneficiaries would be subject to the risk that the benefits made available to them would prove insufficient. Moreover, the waiver would limit the amount of federal Medicaid funds that South Carolina can receive over the next five years, which could result in further reductions in coverage, as well as in decreases in payments to health care providers.

South Carolina proposes to replace Medicaid with a system of state-funded “personal health accounts,” which beneficiaries would use either to purchase health care services directly from providers or to enroll in private insurance plans or private health care networks. For adult beneficiaries — the vast majority of whom have incomes below the poverty line — the result would be less health coverage. Private plans would not be required to provide the range of benefits now offered to adults under Medicaid. As a result, beneficiaries — especially those who have significant disabilities and consequently often need multiple prescriptions and doctor visits — would face a significant increase in out-of-pocket costs for health care.

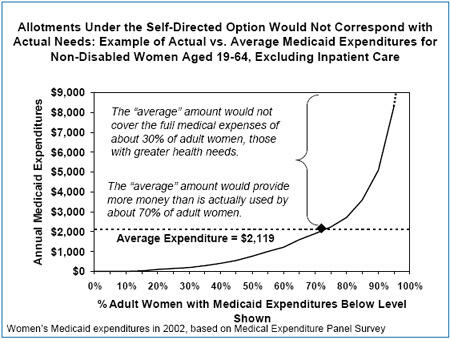

Moreover, flaws in the state’s proposed method for determining the size of each individual’s personal health account would leave many people who are in poorer-than-average health unable to afford the health services they need, even as other people (particularly those in better-than-average health) had money left over in their accounts. Within every category of beneficiaries, eachindividual’s account size would be based on the average cost of health care for people in that category. Individuals with above-average health care costs for their category would consequently have accounts that are too small for them. The accounts would be especially inadequate for individuals with serious disabilities or chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, or HIV, since their health care costs are many times the costs of healthy individuals.

Put simply, the biggest losers from South Carolina’s proposal would be people who have the greatest health care needs and are at the greatest risk of harm if those needs are not met.

The waiver proposal also raises other issues. In particular, it relies on a delivery system of private insurance plans and medical home networks that does not currently exist in South Carolina. The proposal simply assumes that such a system will emerge and be able to provide beneficiaries with access to the health care services they need. The proposal is not accompanied by any evidence to support this critical assumption.

Finally, the proposal is based on a series of assumptions about the Medicaid program itself — that it costs more than private insurance, that it encourages people to use more health services than they need, and that it is administratively inefficient. Research and data demonstrate that all these assumptions are incorrect. Although the state apparently believes it can save money by replacing a public health insurance program with a privatized approach, the evidence suggests that the state’s proposal would increase the costs of providing health care to covered beneficiaries rather than reduce those costs.

Problems in Implementation of Medicare Prescription Drug Program Show Need for Caution in Making Major Changes in South Carolina’s Medicaid Program

On January 1, 2006, low-income Medicaid beneficiaries who are also enrolled in Medicare stopped receiving their prescription drugs through Medicaid. On that date, they were supposed to begin receiving their prescriptions through the new Medicare prescription drug program. In the first two weeks of this change-over, a growing number of states are being forced to step in to provide coverage (at state expense) to low-income seniors and people with disabilities who are unable to get their prescriptions filled because of widespread problems with the implementation of the new program.*

The implementation of the new prescription drug program is a cautionary tale for South Carolina as it considers making major changes to Medicaid:

- Key federal officials responsible for implementation of the Medicare prescription program repeatedly assured beneficiaries, health care providers, and the states that beneficiaries who had been receiving their drugs through Medicaid would receive their drugs without interruption when the Medicare prescription drug program took effect. In South Carolina, state officials are making similar assurances regarding the continued ability of Medicaid beneficiaries to get all the health care they need. The state claims that numerous managed care plans, medical home networks and other choices will be available to Medicaid beneficiaries even though very few managed care plans and medical home networks currently exist in the state. The state also claims it will have effective systems in place to support the program, including an enrollment counseling program and a way of matching the amount of money deposited in individual health accounts to what beneficiaries are likely to need to pay for health care. However, there is no way of accurately predicting how much health care an individual will need.

- The new Medicare prescription drug program and South Carolina’s proposal to change Medicaid have a number of elements in common — both rely to an unprecedented degree on private insurance plans, rather than a government insurance program, to deliver health care benefits. At least for now, this is causing significant problems in the new prescription drug program. The private insurance plans providing the drug benefit have often been difficult to reach by telephone, and they have not uniformly provided temporary supplies of drugs on an emergency basis as promised by Medicare officials.

In a similar way, South Carolina proposes to turn its Medicaid program over to private plans, going so far as to allow the plans to decide what benefits to provide to all beneficiaries over the age of 18. South Carolina could have similar problems holding the plans accountable when it turns the provision of health care over to them. - The new Medicare prescription drug program is extremely complex. Beneficiaries have been confused by the array of choices, and only a small portion of eligible Medicare beneficiaries have signed up. (Medicare beneficiaries who also are enrolled in Medicaid have all been assigned to drug plans.) The South Carolina waiver proposal also would present beneficiaries with a confusing array of choices. Like Medicare beneficiaries who choose or are assigned to the wrong plan, Medicaid beneficiaries who make the wrong choice could lose access to health care services they need.

*Robert Pear, “States Intervene After Drug Plan Hits Early Snags,” New York Times, January 8, 2006.

Outline of the Proposal

Under the South Carolina proposal, each individual Medicaid beneficiary in the beneficiary categories that would be subject to the waiver would receive a capped personal health account to use to purchase health coverage. The waiver would principally apply to children, parents, pregnant women, and people with disabilities who are not also enrolled in Medicare.

The state would periodically deposit funds into a beneficiary’s account.[3] The amount of the deposits would depend on the beneficiary’s age, sex, eligibility category, and (in some cases) health status.

Individuals could use their personal health accounts in one of four ways:

- Self-directed care: For individuals who choose this option, an amount would be deducted from their personal account to cover inpatient hospital care and “related” services and preventive care; these individuals would purchase all other necessary health care services directly from providers, at Medicaid fee-for-service rates, with the funds remaining in their personal accounts. When the funds in an individual’s account were exhausted, the individual would have to purchase any other needed health care services with his or her own money, up to an annual limit of $250. Once that limit was reached, the individual would be enrolled in a managed care plan or medical home network. (Note: this option would be available for adults but not to children.)

- Private insurance: Individuals who choose this option would use the funds in their personal accounts to purchase coverage from private managed care organizations or other insurance companies and from pharmacy or dental plans. Any funds that remained in an individual’s account after the individual paid the premiums for the coverage he or she purchased could be used for co-payments and for health care services that are not covered by the plan the individual had purchased. The benefit package that the private insurers provided would not have to include various important services now covered under the state’s Medicaid program.

Under this option, the minority of people who are in the poorest health and require the most health care services would be at greatest risk. Their accounts would likely prove insufficient to cover both the premiums for the plan and the additional services that such individuals would need. - Medical home networks: Under this option, individuals would use their personal accounts in their entirety to join medical home networks, which are groups of health care providers that would be organized to serve the state’s Medicaid beneficiaries. Each beneficiary would be assigned to a primary care provider, who would be responsible for authorizing any needed services that the primary care provider could not supply. Each medical home network would be managed by an administrative service organization (ASO). The ASO would share any savings with the state if the cost of services was below what was expected and would bear part of the loss if expenses were higher than expected.

- Employer-sponsored insurance. Under this option, individuals could use their personal health accounts as a contribution toward the employee share of the premium for employer-sponsored insurance, including coverage for family members not otherwise eligible for Medicaid. These individuals and their families would be considered to have “opted out” of Medicaid and would be subject to any benefit limits and cost-sharing requirements that the employer-sponsored plan imposed. Children whose families select this option would no longer be guaranteed all health care services that they need for their health and development, as is currently required by Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program.

Waiver Proposal Based on Faulty Assumptions

South Carolina’s waiver proposal is based in significant part on several assumptions: that Medicaid is less efficient than private health plans, largely because it encourages people to use too many health services; that the state can accurately predict each individual’s need for health care services and thereby set aside an appropriate amount of funds in an individual’s personal health account; and that private managed care plans and provider networks will emerge in the state to serve Medicaid beneficiaries.

The success of the state’s proposal hinges on these assumptions. Yet the state has not offered evidence to support the assumptions, and the available evidence suggests that all of these assumptions are dubious at best, and in some cases are demonstrably incorrect.

Medicaid Provides Comparable Services at Less Cost than Private Insurance

A recent 13-state study contradicts the notion that Medicaid beneficiaries use more health care than they need, finding that adult Medicaid beneficiaries use about the same level of health care services as adults with private insurance.[4] A study of mothers in low-income families found similar results.[5] (Among children, Medicaid has been found to provide better access to preventive services than private health insurance does; this is a desirable outcome that likely reflects the success of Medicaid in facilitating preventive services for children.[6])

Moreover, Medicaid is not costlier than private health insurance. A recent study by Urban Institute researchers for the Kaiser Family Foundation found that Medicaid’s cost per beneficiary is lower than that of private insurance.[7] A separate study by Urban Institute researchers finds that Medicaid’s per-beneficiary costs have been rising more slowly in recent years than those of private insurance.[8]

The notion that Medicaid beneficiaries do not bear any of the financial responsibility for their health care also is incorrect. Recent studies show that, on average, adults on Medicaid pay a larger percentage of their income in out-of-pocket medical expenses than do non-low-income individuals with private insurance. (In dollars terms, Medicaid beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs are lower, but as a percentage of income, their costs are higher. This includes out-of-pocket costs for health care services that Medicaid does not cover.) Moreover, studies indicate that in recent years, the share of Medicaid beneficiaries’ income that is consumed by out-of-pocket medical expenses has been rising twice as fast as their incomes. Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities bear especially high out-of-pocket costs.[9]

Risk Adjustment” Cannot Predict an Individual’s Need for Health Care Services

A critical question regarding South Carolina’s proposal is whether the state would be able to determine the right amount of funds to deposit in each beneficiary’s personal health account to enable the beneficiary to purchase necessary health care services. The state says it will determine the amount of funding for each account through a process known as “risk adjustment.”

An individual’s need for health care is, however, inherently unpredictable. Previously healthy individuals may develop serious illnesses or conditions. No system of risk adjustment has ever been developed that can predict with precision what a specific individual will need for health care from one year to the next.

Under the South Carolina proposal, the state would begin by assigning each Medicaid beneficiary a “rate category” based on his or her age, sex, eligibility category, and (in some instances) health status. For each rate category, the state then would determine the average amount that Medicaid spent on the beneficiaries in that category in a base year. That average amount, adjusted upward to reflect the increase in health care costs since the base year, would be deposited in the personal health account of each person in the rate category.

This process is similar to the way in which states set per capita payments for their Medicaid managed care programs. Risk adjustment works relatively well in the managed care context because each plan enrolls a mix of individuals: while some individuals will cost the managed care company more than the amount it receives from the state to cover them, other individuals will cost the company less than that amount. Thus, if the plan receives a flat payment per person that represents average costs over all of its enrollees, the plan will come out behind on some people and ahead on others and be able to cover its costs overall.

Using risk adjustment for personal health accounts as South Carolina proposes, however, is very different. Since each account would cover only a single individual, funds deposited in accounts could not be shifted from people with relatively low health costs to people who turn out to have relatively high health costs. As a result, some people would use up the money in their accounts and be unable to afford health care services they need, while at the same time, other people would have leftover funds in their account that they do not need.

For example, the graph below (which was developed using a process similar to the one South Carolina proposes to use to set the amounts it would deposit in the accounts) shows that average annual Medicaid expenditures for non-disabled adult women exceed the actual Medicaid expenditures for about 70 percent of these women, while being lower than the actual expenditures for the remaining 30 percent of these women. (These data are based on analyses of the 2002 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, a federally sponsored national survey of health care costs and usage.) If South Carolina allocated the average amount to eachwoman’s personal health account, approximately 30 percent of such women — those who have the most serious medical problems and health care needs — would have insufficient funds to purchase the health care services they needed. These women’s health could suffer, in some cases seriously.

Further evidence that some people have much greater health care needs and costs than others also can be found in another analysis of data from the 2002 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which showed that 10 percent of the individuals in the survey accounted for 72 percent of the health care costs.[10] This is why basing the size of each individual’s health account on the average expenditure for an entire category of people does not work: the average amount will always be less than some people need to purchase adequate health care services and much less than the sickest people need.

South Carolina claims it will take individuals’ health status into account when assigning them to rate categories.[11] This often will not be possible, however: many individuals will not have been on Medicaid long enough for the state to obtain a history of their use of health care services.[12] Furthermore, over the course of a year, some people who have used relatively few health care services in the past will become ill with chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, or diabetes. Their past health status will not have provided a good guide to their current health needs, and their health accounts are likely to be too small to pay for the health care they now require. Finally, even when the state can reasonably estimate an individual’s health care needs, the accounts will remain insufficient for those individuals whose costs are above the average for their rate category.

The Self-directed Care Option

The South Carolina proposal implicitly recognizes the danger of leaving individuals with chronic health care conditions on their own to purchase health care; it states that people with a “history of unstable expensive acute care crises” will not be permitted to choose the self-directed care option. (Individuals who lack a primary care physician or who are unable to “demonstrate a reasonable understanding of their health care needs” also will not be permitted to elect this option.) As just noted, however, each year many people who have not previously been ill — and thus do not have a history of expensive health care episodes — will develop an illness or condition or have an accident that requires costly care.

The revised waiver proposal softens the impact of choosing self-directed care for people who exhaust their personal health accounts, by limiting their annual out-of-pocket expenses to $250 for an individual. Once their out-of-pocket expenses reach that amount, these beneficiaries would be required to enroll in a medical home network or managed care plan. But even with this new feature of the plan, it is likely that a substantial number of beneficiaries will be unable to get needed health care services, because they will be unable to come up with the $250 they will have to spend on health care services before this coverage kicks in.

A perverse aspect of the proposal is that while some beneficiaries in poorer health would be driven to forgo care because their accounts would be depleted and they could not afford to pay for health care services themselves, some other beneficiaries with many fewer health care needs would end up with more money in their accounts than they needed and would be allowed to retain some of the unused funds remaining in their accounts. Because such beneficiaries would be able to retain a significant portion of the funds deposited in their accounts that turned out not to be needed for their health care, the self-directed accounts would likely cost the state more money than the state would spend by simply paying for necessary health care for beneficiaries.[13]

The Managed Care Option

While less risky than the self-directed accounts, the option of choosing a managed care plan also would carry risks for beneficiaries. The premiums charged by the managed care plans would vary and be based on the benefits the plans provided. Beneficiaries who suffered a decline in health status could find that the plan they had selected did not provide the benefits they now needed or that the benefits were limited in amount, duration or scope. These beneficiaries would have to pay for the needed health care services their plan did not cover with any funds that remained in their personal health accounts, which could quickly be exhausted. Once they expended the funds remaining in their accounts, they would have to pay out of pocket for necessary services not covered by their health plans.

Moreover, while beneficiaries were bearing the risk of having to pay from their own pockets for various services they needed, the state would be protecting managed care companies from risk. The state proposes to provide “reinsurance” to managed care plans to “mitigate the risk [to those companies] of high-cost beneficiaries.” After a managed care plan spent a certain amount, the state would share further costs with the plan. The fact that the state believes it necessary to expend funds providing reinsurance to managed care plans to induce the plans to participate in the new program is yet another indication of the inherent problems in attempting to match a premium charge with an individual’s (rather than a group’s) need for health care services.

State Lacks Needed Managed Care Plans and Medical Home Networks

Another concern regarding the state’s proposal is that South Carolina lacks sufficient private insurers to handle the many Medicaid beneficiaries who would choose or be directed into the private insurance option or the medical home network option. In 2004, only 6.1 percent of all South Carolina residents were enrolled in health maintenance organizations,[14] and the state’s Medicaid program ranked 47th in the nation in managed care participation.

- Only 8.4 percent of South Carolina’s Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in a Medicaid managed care plan in 2004.[15]

- Only two Medicaid managed care plans exist in the state, and those plans currently cover only 29 of the state’s 46 counties. [16]

- Adults with disabilities and children with special health care needs are not currently enrolled in managed care at all in South Carolina.

- South Carolina has just begun to develop medical home networks. Only 17 counties have medical home networks that include more than one medical practice.

Given the very low rate of managed care participation in South Carolina, it is doubtful that beneficiaries will have a full array of managed care choices. Beneficiaries who reside in counties without a medical home network would essentially be compelled to choose between the risky self-directed option and a managed care plan that may not provide all of the benefits they need. Beneficiaries in areas without either managed care plans or medical home networks would have no alternative to the self-directed option.

The South Carolina waiver proposal asserts that the new program would “unleash the creative and technological forces of the private market by freeing the market from current administratively burdensome rules and restrictions,” and that the “greatest value from this demonstration will be attained through the new creative models yet to come.” This extremely rosy scenario — that a sufficient number of new private health plans will arise to compete for Medicaid customers in an extremely short timeframe in a state that until now has had extremely low managed care participation — is not justified by the current marketplace for health care in the state. If the state’s optimism proves unfounded, as could well be the case, the consequences will be most severe for sicker Medicaid beneficiaries, who are likely to fare badly both under self-directed accounts and under plans that offer significantly fewer benefits than the current Medicaid program does.

Waiver is Likely to Increase Costs for the State Even As Many Beneficiaries Pay More for Fewer Services

South Carolina assumes that the waiver it is proposing would save the state money by curtailing administrative costs and “reducing the rate of increase in utilization and payment rates for Medicaid services subject to the demonstration.” The state has presented no evidence, however, to show how such savings would actually be achieved. A careful examination of the proposal indicates that it would be more likely to increase state costs than to reduce them, even as it scaled back the benefits available to many beneficiaries.

Most of the Beneficiaries Included in the Waiver Proposal are Children and Parents, Who Account for a Minority of the State’s Medicaid Costs

The proposed waiver would encompass only 40 percent of the state’s expenditures on Medicaid. Seniors and people with disabilities who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid — a group known as the “dual eligibles” — would not be covered by the waiver proposal; no changes would be made in how their care is managed or delivered. These beneficiaries constitute only 12 percent of the state’s Medicaid caseload but account for about 40 percent of the state’s Medicaid costs. Long-term care services for other beneficiaries also would be outside the waiver.

Most of the beneficiaries who would be covered under the waiver are children, their parents and pregnant women.[17] In South Carolina, 72 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries are children, parents with incomes below 50 percent of the poverty line, or pregnant women. The cost of providing health care coverage to these beneficiaries, however, constitutes just over one-third of the Medicaid program’s cost.[18]

The most recent data on Medicaid expenditures from 2003 show that Medicaid costs per beneficiary in South Carolina are $1,753 per year for children and $1,907 per year for non-disabled adults under the age of 65.[19] Even considering increases in Medicaid costs since 2003, Medicaid coverage is considerably less costly than care in the private market. In 2005 in the southern states, the average annual premium for employer coverage was $3,950 for an individual and $10,507 for family coverage.[20] Although South Carolina asserts that the waiver will control “the rate of growth of future Medicaid expenditures through widespread use of managed care and consumer-directed enhanced benefits,” the state is unlikely to lower its Medicaid costs substantially by focusing on children and non-disabled adults whose care is already relatively inexpensive.

The Waiver Would Significantly Increase Administrative Costs

Another reason that South Carolina is unlikely to achieve savings through the proposed waiver is that the complicated design of the proposal would require a substantial increase in the amount the state spends to administer its Medicaid program. The two principal reasons why Medicaid costs less than private health insurance for comparable beneficiaries are that Medicaid’s payment rates to providers tend to be lower than the rates that private insurance plans pay and that Medicaid’s administrative costs are about half those of private plans. According to estimates by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the federal agency that oversees these programs, Medicaid’s administrative costs average 6.9 percent of total program costs nationally, while the administrative costs of private health plans average 13.9 percent.

The state’s waiver proposal says that the new program is intended to limit unnecessary administrative costs, noting that nationally, “over twenty cents of each healthcare dollar [covering the private sector as well as the public sector] is spent on administration.” Yet the state recently reported that the administrative costs in the South Carolina Medicaid program are only 4.6 percent of total program costs, well below the national average. [21] (It also may be noted that the state’s total Medicaid expenditures grew considerably more slowly in 2004 than the national average — 5.8 percent versus 9.3 percent.)

According to the waiver proposal, the state would contract with:

- A vendor both to develop electronic cards for the personal health accounts and to track and report on how beneficiaries use their accounts;

- An enrollment broker to maintain and provide information about the various health care choices open to beneficiaries and to help beneficiaries evaluate the options available to them;

- Managed care plans;

- Administrative service organizations to oversee the medical home networks;

- A dental benefits manager; and

- A transportation broker.

Each of these entities would have its own administrative structure and would expect to make a profit on its contract.

Moreover, beneficiaries would have to track their out-of-pocket expenses, and these expenses would have to be verified to determine whether an individual’s out-of-pocket expenses had reached the annual limit on such costs. Once the annual limit was reached, the state would have to operate a system of notifying providers to stop charging co-payments. Beneficiaries in self-directed care who reached the limit would have to be enrolled in a private plan or medical home network. Developing and operating the systems needed to produce such results would entail additional costs.

Another set of costs would be incurred in providing managed care plans with reinsurance for high-cost beneficiaries. In addition, healthier beneficiaries who did not spend all of the funds allotted to their accounts would get to retain a portion of the unspent amounts in their accounts, adding still another cost.

Finally, the state would have to provide funds to start up and administer the new option to allow beneficiaries to use their personal health accounts to contribute to the cost of employer-sponsored insurance. A recent review of similar programs in five states found they achieved savings only if enrollment was high enough for the resulting savings to be sufficient to offset the start-up and administrative costs involved, and that in most states, enrollment was not high. Enrollment in the five state programs examined ranged from 73 in Utah to 10,564 in Oregon.[22] To date, South Carolina has not made available its estimate of the number of Medicaid beneficiaries that have access to employer-sponsored coverage, so it is impossible to determine whether enrollment in employer-based coverage could offset the new costs.

With the various new costs that South Carolina would have to incur to implement its proposal, the historically low administrative costs the South Carolina Medicaid program has borne could increase substantially. That would divert resources needed to provide health care services to beneficiaries and also place further pressure on already low provider payment rates.

For Adults, Some Health Care Services Would Be Eliminated, Others Curtailed

There appear to be no benefit standards for self-directed care, so adults who choose this option would be limited to whatever health care services they could afford to purchase with the funds in their personal health accounts. Beneficiaries who suffer injuries or unexpected illness would likely be left with insufficient resources to purchase the health care they need.

For adults who choose the private insurance option, the minimum benefit package would be limited to services that federal Medicaid law designates as “mandatory,” as well as to prescription drugs and durable medical equipment. The list of “mandatory” Medicaid services, however, is not — and was not intended to be — a comprehensive list of all important health care services. It was always intended that state Medicaid programs would offer a number of other services, as well, and the Medicaid program of every state in the nation does so. For example, prescription drugs are not included in the list of “mandatory” medical services, but they are essential to health. Similarly, services like physical and speech therapy are not “mandatory” but can be critical for people with disabilities and those who have suffered a stroke.

South Carolina’s current Medicaid program covers a number of “optional” services, including emergency dental services, vision care, and hearing aids, as do the Medicaid programs of the vast majority of states. Under South Carolina’s waiver proposal, private insurance plans would not need to cover any “optional” services other than prescription drugs and durable medical equipment.

Even “mandatory” services (as well as prescription drugs and durable medical equipment) could be limited, since the private plans would be allowed to restrict the amount of these benefits.[23] Beneficiaries thus could be at risk of having to pay significant amounts for health care services that are not covered. This could be especially harmful to people with disabilities because the funds remaining in their accounts are likely to be insufficient to cover necessary health care services that are not covered by the plans.

This aspect of the state’s proposal would be especially dangerous for people with severe disabilities or chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, or HIV. Such people generally require a higher level of health care services than the average Medicaid beneficiary. They can end up in the hospital or worse if needed medications are not obtained or they are unable to see a doctor when necessary.

Finally, the health care services that are covered could be cut back significantly for 19- and 20-year olds. Under the waiver, 19- and 20-year olds who are now entitled to comprehensive coverage through Medicaid’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program would lose that coverage. They would be treated as adults and be subject to the limited coverage that could be provided to adults under the waiver.

Adults Would Pay Significantly More for Health Care

Currently, most Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina are charged co-payments, ranging from $1 to $3 per service for most medical services. Federal Medicaid law exempts pregnant women and children from co-payments and other forms of “cost-sharing,” in recognition of the critical importance of preventive and primary health care services to successful birth outcomes and children’s development.

Under the waiver proposal, out-of-pocket costs would increase significantly for beneficiaries other than children and pregnant women, regardless of which the options they chose (self-directed care, private insurance, or medical home networks).

- Those selecting the self-directed care option would have to pay $40 for each hospitalization. In addition, if they exhausted the funds in their personal health accounts, they would have to pay the full cost of any additional health care services they needed, up to $250 per individual per year.

- For those electing the private insurance option, the insurer would set its own co-payment charges within ranges set by the state. There would be an annual limit on co-payment charges of $250 for individuals and $400 for families. It is not clear how beneficiaries’ expenditures would be tracked so providers would know to stop charging co-payments to beneficiaries when they reached the limit.

- For those electing a medical home network, some co-payments could be set well above the levels Medicaid currently allows. Beneficiaries would be charged up to $40 per inpatient hospital visit, $10 per outpatient visit, and $4 or $6 per brand name drug. They also would be charged $1 per generic drug prescription.

The vast majority of Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina have incomes below the poverty line. (The poverty line was $798 per month for an individual and $1,341 per month for a family of three in 2005.)[24] Faced with substantially increased cost-sharing charges, along with the loss of coverage for certain health care services that Medicaid now covers, a large number of low-income families, seniors, and people with disabilities likely would lose access to some health care services they need.

The co-payments in the revised waiver are not as large as those in the original waiver proposal. Nevertheless, the increases in co-payments would be substantial. Numerous studies of the effects of cost-sharing charges have found that for people with low incomes, even modest increases in co-payments can result in significantly reduced access to care, and often in a deterioration of patients’ health.

- The RAND Health Insurance Experiment, considered the landmark study of this issue, found that while co-payments did not adversely affect the health of middle- and high-income people, they did lead to poorer health for those with low incomes. The Rand study found that co-payments led to a marked reduction in “episodes of effective care” among low-income adults and children. As a consequence, health status was considerably poorer among low-income adults and children who were required to make co-payments to obtain care than among comparable low-income adults and children who were not subject to co-payments. As one example, co-payments were found in the RAND experiment to increase the risk of death by about 10 percent for those low-income adults who were at risk of heart disease.[25]

- A recent small survey in Minneapolis’ main public hospital that examined the effects of modest co-payments instituted in that state’s Medicaid program produced similar findings. Slightly more than half of those surveyed reported being unable to obtain their prescriptions at least once in the last six months because of the co-payment charges. Those who failed to obtain their prescriptions at least once experienced a marked increase in subsequent emergency room visits and hospital admissions, including admissions for strokes and asthma attacks.[26]

- Another such piece of research, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, found that after Quebec imposed co-payments for prescription drugs on adults who were receiving welfare, these individuals filled fewer prescriptions for essential medications and emergency room use subsequently climbed 88 percent among these adults. The number of “adverse events” such as death and hospitalization rose by 78 percent.[27]

After paying for food, clothing and shelter, low-income individuals often have little money left to meet the costs of health care services. When the cost of health care services increases, these individuals often respond by doing without some or all of the services they otherwise would use.[28] The impact of facing a higher charge each time that a health care service or medication is used is most severe for beneficiaries with serious health problems, such as diabetes, heart disease, mental health problems, or HIV. These individuals require more health care services and medications and consequently face a larger volume of co-payments.

Federal Funding Limitations Could Further Weaken Coverage

Waivers submitted under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, as South Carolina’s waiver has been, must be “budget neutral.” This means the federal government will not spend more under the waiver than it would spend in the waiver’s absence.

South Carolina is proposing to achieve budget neutrality by accepting a cap on increases in federal funding for its Medicaid program that averages 7.7 percent per year per beneficiary subject to the waiver. This would represent a marked departure from Medicaid’s current financing system, which guarantees beneficiaries all covered services they need and guarantees federal matching funds to each state to cover a specified percentage share of the costs of those services.

Under the proposed cap, federal Medicaid funding per beneficiary would be allowed to increase at a rate that is based on the average rate of growth in prior years of South Carolina’s costs in serving the beneficiary population that the waiver would cover. If the state’s Medicaid enrollment increased, the state would receive additional federal funds to serve the added beneficiaries. The state would not receive additional federal funds, however, to help pay for unanticipated increases in health care costs per covered beneficiary, such as the costs that could result from the development of new drugs, advances in medical technology, or a flu epidemic or natural disaster.[29] In such cases, South Carolina would be forced to choose between covering the added costs entirely with state funds, cutting eligibility or benefits (or provider payments), and reducing health care coverage by shrinking the size of beneficiaries’ personal health accounts.

South Carolina expects to stay within the funding cap and to control costs by limiting increases in the amounts placed in the personal health accounts that are provided to beneficiaries. This would limit the state’s exposure to increased costs. But if the amounts placed in the personal accounts increase by less each year than the rise in health care costs, coverage will be steadily diminished over time, and beneficiaries will be increasingly less likely to obtain the health care services they need. Managed care plans almost certainly will respond to a decrease in available funds (relative to costs) by reducing benefits, and beneficiaries in the self-directed option will be more likely to exhaust their accounts.

Recent experience suggests it is distinctly possible that South Carolina could end up under the waiver with a funding cap that fails to keep pace with increases in the cost of treating the state’s Medicaid beneficiaries. The actual level of the cap on federal Medicaid funding will have to be negotiated in the coming months between South Carolina and the federal government. It is worth noting that in negotiations with the federal government over a previous waiver that covered prescription drugs for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries, South Carolina ended up agreeing to a federal funding cap that was adjusted upward each year at a substantially slower rate than the rate at which the health care costs of the beneficiaries in question had been rising prior to the waiver.

In the three years prior to approval of that waiver, health care costs for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina rose at an average annual rate of 11.1 percent, and federal matching funds for those costs also rose at an 11.1 percent rate. Yet South Carolina accepted, as part of that waiver, a cap of 7.4 percent on annual increases in federal matching funds for the Medicaid costs of these beneficiaries. South Carolina agreed to that limit even though the limit was lower than the comparable limit imposed on the other three states that secured similar waivers.[30]

End Notes

[1] The waiver would not affect those beneficiaries who are eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare or children in foster care.

[2] This paper revises and updates a paper on the June waiver proposal, which was issued in August.

[3] Balances in the account at the end of a period would roll over to the next period within a benefit year. At the end of a year, an “actuarially determined percentage” of any unexpended funds would roll over in the account to the following year.

[4] Teresa Coughlin, Sharon Long and Yu-Chu Shen, “Assessing Access to Care Under Medicaid: Evidence for the Nation and Thirteen States,” Health Affairs, 24(4):1073-1083, July/August 2005.

[5] Sharon K. Long, Teresa Coughlin and Jennifer King, “How Well Does Medicaid Work in Improving Access to Care?” Health Services Research, 40(1): 39-58, February 2005.

[6] Lisa Dubay and Genevieve M. Kenney, "Health Care Access and Use Among Low-income Children:

Who Fares Best?" Health Affairs 20(1): 112-21, January/February 2001.

[7] Jack Hadley and John Holahan, “Is Health Care Spending Higher under Medicaid or Private Insurance?” Inquiry, 40 (2003/2004): 323-42.

[8] John Holahan and Arunabh Ghosh, “Understanding the Recent Growth in Medicaid Spending, 2000-2003,” Health Affairs web exclusive, January 26, 2005

[9] Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, “Out-Of-Pocket Medical Expenses For Medicaid Beneficiaries Are Substantial And Growing, “(Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2005)

[10] Andy Schneider, et. al., “Medicaid Cost Containment: The Reality of High-Cost Cases,” (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2005).

[11] South Carolina plans to use a case-mix system designed by Johns Hopkins University to categorize individuals based on their health status. The “ACG Case-Mix System” has been used for a number of purposes, including managed care rate-setting, but it has not been used to determine individual allocations for health care expenditures. The case mix system is described at www.acg.jhsph.edu.

[12] One large study found that 35 percent of beneficiaries were enrolled for a year or less. Pamela Farley Short and others, “Churn, Churn, Churn: How Instability of Health Insurance Shapes America’s Uninsured Problem,” (New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, 2003)

[13] A proposal to allow ten states to establish Health Opportunity Accounts for some Medicaid beneficiaries was included in the budget reconciliation legislation passed by the U.S. House of Representatives in November 2005. This proposal has some similarities to the personal health accounts proposed by South Carolina. The Congressional Budget Office has found that allowing these accounts would increase both state and federal Medicaid costs. Edwin Park and Judith Solomon, “Health Opportunity Accounts for Low-Income Medicaid Beneficiaries: A Risky Approach,” (Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2005).

[14] Managed Care Penetration by State and Region, 2004 from InterStudy Competitive Edge: Managed Care Industry Report Fall 2004 at http://www.mcareol.com/factshts/factstat.htm.

[15] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicaid Managed Care Penetration Rates as of December 31, 2004,” available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/medicaid/managedcare/mmcpr04.pdf.

[16] According to the waiver proposal, expansion of managed care into two additional counties is awaiting approval.

[17] The only other beneficiaries included in the waiver are people with disabilities who do not receive Medicare.

[18] Presentation of Robert Kerr, Director of South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, August 17, 2005.

[19] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2003 Medicaid Statistical Information System data.

[20] “Employer Health Benefits Survey: 2005 Annual Survey,” Exhibit 1.14 (Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Education Trust).

[21] Medicaid and SCHIP Budget Estimates, Forms CMS-37 and CMS-21B, May 2005 submission.

[22] Joan Alker, “Premium Assistance Programs: How Are they Financed and Do States Save Money?” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, October 2005).

[23] There is some confusion in the waiver proposal on this point. The proposal states that plans would have to provide benefits in accordance with the federal requirement that the benefits be sufficient in amount, duration and scope to serve their purpose, but the proposal also states repeatedly that the plans could restrict the amount and scope of the benefits.

[24] The only major exception are pregnant women and infants, who can be eligible for Medicaid in South Carolina if they have incomes up to 185 percent of the poverty line, and children from age one to 18, who can be eligible if they have incomes up to 150 percent of the poverty line.

[25] Joseph Newhouse, Free for All? Lessons from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment, Harvard University Press, 1996.

[26] Melody Mendiola, Kevin Larsen, et.al. “Consequences of Tiered Medicaid Prescription Drug Copayments Among Patients in Hennepin County, Minnesota,” Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis, MN. Posted October 2005 at http://www.hcmc.org/depts/medicine/documents/Hennepincopaymentstudy.pdf.

[27] Robyn Tamblyn, et al., “Adverse Events Associated with Prescription Drug Cost-Sharing among Poor and Elderly Persons,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(4): 421-429, January 2001. In this study, the low-income people were adults who were on welfare.

[28] Leighton Ku, “The Effect Of Increased Cost-Sharing In Medicaid: A Summary Of Research Findings”, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, revised July 7, 2005, Bill Wright, Matthew Carlson, Tina Edlund, Jennifer DeVoe, Charles Gallia and Jeanene Smith, “The Impact of Increased Cost-sharing on Medicaid Enrollees,” Health Affairs, 24(4):1107-15, July/August 2005.

[29] Cindy Mann and Joan Alker, “Federal Medicaid Waiver Financing: Issues for California,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2004).

[30] Jocelyn Guyer, “The Financing of Pharmacy Plus Waivers: Implications for Seniors on Medicaid of Global Funding Caps,” (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2003)

More from the Authors