- Home

- States Should React Cautiously To Recent...

States Should React Cautiously to Recent Income Tax Growth

April Surge Provides Opportunity to Invest in Infrastructure, Boost Reserves

Recent tax collections are considerably higher than last year in most states and, in many cases, exceed states’ projections when they adopted their current budgets in the spring of 2012. In 31 states for which data were available in June 2013[1] , state tax collections in the first ten months of fiscal year 2013 were 5.7 percent higher than in the same period last year, on average.

A closer look into the tax collection reports available in June 2013 reveals that:

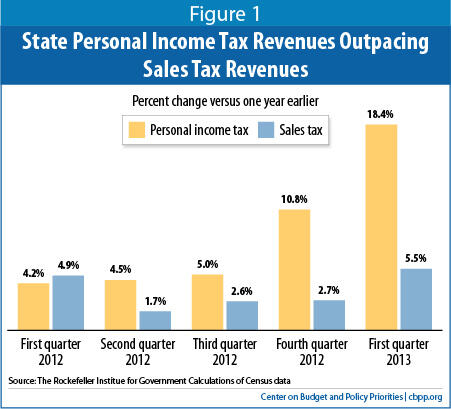

- Much of the recent growth is in the income tax. With two months left in the fiscal year, the typical state has collected 8.3 percent more personal income taxes than it did in the same period last year. Sales taxes have grown more slowly. This is, in part, the latest demonstration of the fact than income taxes rise more rapidly than sales taxes during periods of economic growth.

- The revenue growth and particularly income tax growth is nationwide. Some 26 of the 30 states for which data are available experienced double-digit growth in income taxes between April 2012 and April 2013.

- While a portion of the income tax growth reflects the economic recovery, an additional portion reflects wealthy taxpayers shifting income into 2012 that they would have received in 2013 in anticipation of federal tax rate increases in 2013.

- Even with this recent growth, state tax revenues have not recovered from the Great Recession. Revenues likely still remain more than 3 percent below pre-recession levels, after adjusting for inflation. And because of the one-time nature of much of the recent revenue growth, revenue growth is likely to slow again.

These findings have three important policy implications for states.

First, states without income taxes are missing out on revenue. Part of the recent revenue boost reflects the fact that income taxes are better at growing with the economy than sales or other taxes. States that are considering repealing or shrinking their income tax would lose out on this advantage now that the economy appears to be in a sustained recovery.[2]

Second, national factors, not state actions, are driving this revenue growth. Income tax revenues are up across much of the country, regardless of whether a state has cut tax rates or not. So, claims that these revenue gains reflect positive “supply-side” impacts of tax cuts appear unfounded. (Not surprisingly, California’s voter-approved tax rate increase has produced a lot of new revenue.)

Third, states should proceed with caution in using these funds. While both the improving economy and the temporary tax shift clearly have contributed to revenue growth, it remains unclear how much of the increased growth comes from each of those causes. A sound strategy — applicable this year as in other years — is that states should use the higher-than-anticipated year-end balances that often result from revenue surges like these to address one-time spending needs such as paying down debt, boosting reserves, or addressing neglected infrastructure needs, rather than permanent tax cuts or new programs.

Here’s some more detail on this revenue surge, what it means, and what it doesn’t mean.

Revenue Growth Shows That It Pays to Have an Income Tax

Much of the recent gains in personal income taxes reflect rapid increases in the incomes of wealthy individuals over the last year. The Great Recession appears to be following the pattern of recent recessions, in which the incomes of the wealthy recover well before those of low- and middle-income individuals and families. For example, a recent study of IRS data found that the lion’s share of the gains in family income since the recession have gone to the top: the incomes of the top 1 percent of families grew by 11.2 percent between 2009 and 2011, on average, but incomes of the remaining 99 percent shrank by an average of 0.4 percent.[4] States typically tax higher incomes at higher rates, so faster income growth for the wealthy boosts income tax collections.

Retail sales tax receipts are recovering more slowly than income taxes. Thus, states that rely more on income taxes (especially progressive income taxes, which set higher rates for higher incomes) than on sales taxes are seeing a more rapid revenue recovery. See Table 1, which compares total tax collections for the first three months of 2012 and 2013.

Preliminary data for April show that this pattern is continuing. Among the 32 states that have published tax collection data for April, the median increase in income tax collections was 27 percent, while sales tax collections grew by only 2.5 percent in the typical state (see Table 2).

Revenue Growth Largely Reflects National Factors, Not State Actions

Income tax collections are growing across the country. Of the 30 states with an income tax that we surveyed, 26 states saw double-digit increases in income tax collections in April, compared to last April.

These robust gains boosted overall tax collections for the fiscal year in most states, as Table 3 shows.

Some of this growth reflects the recovering economy. The stock market has boomed (the Dow Jones Index rose 25 percent in the past year), and the job market is slowly recovering. Employment has risen by 1.9 million jobs since July of 2012.

But a significant share of the recent surge in state personal income tax revenues — which include taxpayers’ final income tax payments for 2012, due April 15 — is likely a one-time bump, as the Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government explained in a recent report.[5] Many wealthy taxpayers sold stocks or collected other income such as bonuses in late 2012 rather than in 2013 in order to avoid the higher federal tax rates (especially on capital gains) scheduled to take effect in 2013. (In the end, the “fiscal cliff” deal averted most of those increases.) These actions boosted state revenue collections around the country, but it was a one-time event.

| Table 1 Tax Collections Have Risen in Most States (Percent Change Jan-Mar 2012 to Jan-Mar 2013) | |

| Alabama | 3.4% |

| Alaska | -42.0% |

| Arizona | 3.4% |

| Arkansas | 4.3% |

| California | 28.9% |

| Colorado | 8.8% |

| Connecticut | 0.8% |

| Delaware | -7.6% |

| Florida | 4.1% |

| Georgia | 5.5% |

| Hawaii | 3.6% |

| Idaho | 0.6% |

| Illinois | 8.1% |

| Indiana | -0.3% |

| Iowa | 4.7% |

| Kansas | 0.6% |

| Kentucky | 0.1% |

| Louisiana | 7.2% |

| Maine | 1.5% |

| Maryland | 9.1% |

| Massachusetts | 7.3% |

| Michigan | 7.1% |

| Minnesota | 39.0 |

| Mississippi | 5.9% |

| Missouri | 5.5% |

| Montana | 11.7% |

| Nebraska | -4.8% |

| Nevada | 20.8% |

| New Hampshire | 1.8% |

| New Jersey | 9.6% |

| New Mexico | 3.7 |

| New York | 7.7% |

| North Carolina | 2.3% |

| North Dakota | -12.8% |

| Ohio | 3.7% |

| Oklahoma | -1.2% |

| Oregon | 12.6% |

| Pennsylvania | 1.6% |

| Rhode Island | -4.1% |

| South Carolina | 8.9% |

| South Dakota | 0.1% |

| Tennessee | 2.1% |

| Texas | 6.1% |

| Utah | -0.3% |

| Vermont | 2.2% |

| Virginia | 3.9% |

| Washington | 5.1% |

| West Virginia | -3.1% |

| Wisconsin | 4.3% |

| Wyoming | -11.9 |

| Total | 8.6% |

| Source: The Rockefeller Institute of Government | |

Officials in some states have attributed their growing tax collections to policy actions taken by the state. Some such claims are stronger than others. California’s voter-approved tax rate increase has clearly produced significant new revenue. But other assertions — such as the Kansas revenue secretary’s claim that April’s improved income tax collections prove that the state’s 2012 tax cuts are paying off in economic growth[6] — appear unfounded, since revenues are up in both tax-cutting and non-tax-cutting states.

More generally, there is little evidence that cutting state income taxes promotes economic growth. Eight major studies published in academic journals since 2000 have examined whether differences in state personal income tax levels affect states’ relative rates of economic growth. Six found no significant effects, and one of the others produced internally inconsistent results.[7]

Revenues Still Haven’t Fully Recovered From the Recession

The Great Recession, the most severe recession in seven decades, blasted holes in state budgets from which they have yet to recover, sharply reducing revenues and causing budget shortfalls totaling well over half a trillion dollars. The most recent Census data, for December 2012, show that revenues remained about 5 percent below where they were five years earlier, after adjusting for inflation.

The revenue surge since the beginning of 2013 will help revenues recover further. If preliminary estimates for January through March are correct, revenues are now just over 3 percent below pre-recession levels, after inflation. But they have still not fully recovered. Meanwhile, the number of students, elderly, and low-income families in need of services has grown.

States Should Focus Year-End Surpluses on Debt Reduction and Overdue Investments

Almost every state is required by law to balance its budget — in other words, in the budget plan that policymakers adopt, projected revenues must meet or exceed projected spending. But estimating future tax collections is inexact in the best of times; it’s even more difficult when the economy is recovering from a crisis that led to record revenue declines. Understandably, therefore, many states’ revenue estimates for the current fiscal year were conservative. So it’s no surprise that a number of states are collecting more revenues than projected.

States should proceed with caution as they consider how to use these surplus revenues. Only time will tell how much of the revenue growth reflects the improving economy (and thus may continue) and how much reflects the late-2012 income shifting described above (and thus is a one-time event). It’s prudent, however, to assume that revenue growth will slow in coming months. Goldman Sachs recently attempted a rough estimate and concluded that “it is likely that as much as half the growth in receipts in Q1 [January through March of 2013] was due to income shifting.”[8]

Permanent tax cuts or major new programs, therefore, may not be sustainable. States can best use the new funds to address one-time spending needs such as paying down debt, addressing neglected infrastructure needs, building up rainy day funds, or making deposits to pension trust funds.

| Table 2 Personal Income Taxes Driving State Tax Growth in April (Percent Change April 2012 to April 2013) | |||

| State | Income | Sales | All Taxes |

| Arkansas | 21.9% | -2.5% | 15.0% |

| Arizona | 37.9% | 5.4% | 20.6% |

| California | 72.0% | 10.4% | 51.1% |

| Colorado | 36.1% | 14.9% | 31.2% |

| Connecticut | 22.5% | 4.5% | 24.0% |

| Florida | N/A | 6.8% | 3.2% |

| Georgia | 26.1% | -13.6% | 13.0% |

| Idaho | 20.4% | 9.2% | 20.3% |

| Iowa | 30.2% | -3.5% | 17.0% |

| Illinois | 31.6% | -1.3% | 26.9% |

| Indiana | 11.0% | 0.3% | 4.4% |

| Kansas | 8.8% | 15.6% | 6.2% |

| Kentucky | 5.5% | -3.3% | -1.7% |

| Louisiana | 39.8% | -4.4% | 3.8% |

| Massachusetts | 19.6% | 2.5% | 14.2% |

| Michigan | 59.0% | 3.3% | 18.3% |

| Mississippi | -26.9% | 2.9% | -7.9% |

| Missouri | 30.7% | 15.4% | 20.5% |

| Nebraska | 75.4% | 1.1% | 46.4% |

| New Hampshire | 12.5% | N/A | 18.2% |

| New Jersey | 29.1% | 3.8% | 20.3% |

| New York | 29.7% | 3.9% | 25.0% |

| Ohio | 27.4% | 0.8% | 19.9% |

| Oklahoma | 14.4% | -3.4% | 14.7% |

| Pennsylvania | 13.7% | -3.2% | 5.0% |

| Rhode Island | 17.2% | 2.3% | 8.9% |

| Tennessee | 48.9% | -0.7% | 9.3% |

| Texas | N/A | 7.2% | 6.3% |

| Vermont | 28.0% | 4.3% | 20.7% |

| Virginia | 5.5% | 0.0% | 2.3% |

| West Virginia | 31.5% | -4.5% | 15.0% |

| Wisconsin | 12.4% | 3.0% | 7.6% |

| Median Change | 26.7% | 2.5% | 15.0% |

| Notes: New Hampshire and Tennessee tax only interest and dividends. Source: CBPP survey of state websites | |||

| Table 3 Personal Income Taxes Driving State Tax Growth This Fiscal Year (Percent Change June 2011-April 2012 to June 2012-April 2013*) | |||

| State | Income | Sales | All Taxes |

| Arkansas | 9.1% | 0.3% | 6.1% |

| Arizona | 12.3% | 4.4% | 6.2% |

| California | 36.6% | 1.6% | 20.9% |

| Colorado | 16.5% | 5.4% | 14.5% |

| Connecticut | 6.3% | 0.6% | 5.7% |

| Florida | N/A | 5.6% | 6.3% |

| Georgia | 8.3% | 0.9% | 5.7% |

| Idaho | 5.9% | 7.3% | 6.7% |

| Iowa | 10.4% | 4.4% | 7.9% |

| Illinois | 8.9% | 0.9% | 8.1% |

| Indiana | 4.8% | 2.3% | 2.7% |

| Kansas | 3.6% | 3.7% | 2.5% |

| Kentucky | 5.6% | -0.9% | 1.9% |

| Louisiana | -17.6% | -3.4% | 6.1% |

| Massachusetts | 8.2% | 1.6% | 5.3% |

| Michigan | 38.0% | 1.1% | 8.9% |

| Mississippi | 2.2% | 2.5% | 1.4% |

| Missouri | 9.9% | 2.0% | 5.7% |

| Nebraska | 17.5% | 2.6% | 10.8% |

| New Hampshire | 17.3% | N/A | 4.7% |

| New Jersey | 12.8% | 3.1% | 6.9% |

| Ohio | 13.5% | 3.8% | 11.1% |

| Oklahoma | 4.0% | 4.5% | 0.9% |

| Pennsylvania | 5.8% | 0.8% | 3.8% |

| Rhode Island | 2.2% | 3.2% | 2.3% |

| Tennessee | 47.0% | 1.7% | 3.9% |

| Texas | N/A | 7.7% | 8.3% |

| Vermont | 10.7% | 1.4% | 5.9% |

| Virginia | 5.0% | 3.6% | 4.2% |

| West Virginia | 6.6% | -3.0% | 0.9% |

| Wisconsin | 7.0% | 1.9% | 4.5% |

| Median Change | 8.3% | 2.2% | 5.7% |

| Notes: New Hampshire and Tennessee tax only interest and dividends. Net Sales and Use Tax reported for Georgia. 2012 figures were estimated based on the percent change reported for 2013 for Arizona, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Michigan. For all states, amounts shown are year-to-date through April of the state’s fiscal year. The Michigan fiscal year starts on October 1 and the Texas fiscal year starts on September 1. Source: CBPP Survey of state websites | |||

End Notes

[1] This analysis was conducted in June 2013 when this paper was originally released.

[2] See for example, Erica Williams, “North Carolina Lawmakers Chart the Wrong Course,” Off the Charts blog, May 23, 2013, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/north-carolina-lawmakers-chart-the-wrong-course/.

[3] For a more detailed discussion, see Elizabeth McNichol, “Strategies to Address the State Tax Volatility Problem,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 18, 2013.

[4] Emmanuel Saez, “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” University of California, Berkeley, January 23, 2013.

[5] Don Boyd and Lucy Dadayan, “Time Bandits? State Income Taxes Surge in April,” The Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, May 8, 2013.

[6] “Revenue Secretary Says Tax Cuts are Working,” LJWorld, May 5, 2013.

[7] Michael Leachman et al., “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: A Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 21, 2013.

[8] “US Daily: State Revenues Growing Strongly, For Now (Phillips),” Goldman Sachs Global Economics, Commodities and Strategy Research, May 20, 2013.