Congress must act soon to avert a nearly 20 percent benefit cut in Disability Insurance (DI), a critical part of Social Security that serves as a lifeline for workers who can no longer support themselves because of a life-changing illness or injury. Some congressional Republicans want to force the DI trust fund to borrow money from Social Security’s much larger retirement and survivors fund.[1] This is misguided. Congress shortchanged DI in rebalancing money between the disability and retirement funds in the past, helping to create a shortfall that borrowing will not fix. Instead, borrowing would set the stage for potentially draconian cuts in DI when the loans come due.

Advocates of so-called “interfund borrowing” sometimes invoke as a precedent the one time it was used, in the early 1980s. The circumstances, however, were very different then. Policymakers allowed Social Security’s retirement fund to borrow from the DI fund at the same time that they began addressing overall Social Security solvency; ultimately, they enacted legislation giving the retirement fund a clear way to repay its debt and strengthening the program as a whole. This time, supporters of borrowing offer no proposals that would increase DI’s resources (or cut benefits) enough to enable it to repay a loan.

Instead of interfund borrowing, Congress would be wise to rebalance, or “reallocate,” Social Security’s revenues between the program’s two trust funds, as Congress has done many times in the past in both directions, with large bipartisan majorities. Shifting a small portion of payroll tax receipts to the DI trust fund would avert a sudden cut in DI benefits, have only a tiny effect on the solvency of the much larger retirement fund, and give the President and Congress time to focus on strengthening and restoring long-term solvency to Social Security as a whole.

Two trust funds pay for Social Security benefits: the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) fund, which pays benefits for retirees and survivors of deceased workers, and the Disability Insurance (DI) fund, which pays benefits for disabled workers. While the two funds operate separately, all of Social Security’s programs are closely linked.[2] The retirement, survivors, and disability programs have many similar rules, such as those related to the tax base, the work history required to become insured for benefits, the benefit formula, and cost-of-living adjustments. Workers and their families may receive benefits from either trust fund at different points in their lives. Workers’ paychecks simply show a deduction for “Social Security tax” (currently 6.2 percent of earnings up to $118,500, matched by the employer), and few know — or have reason to care — how that amount is apportioned between the two trust funds.

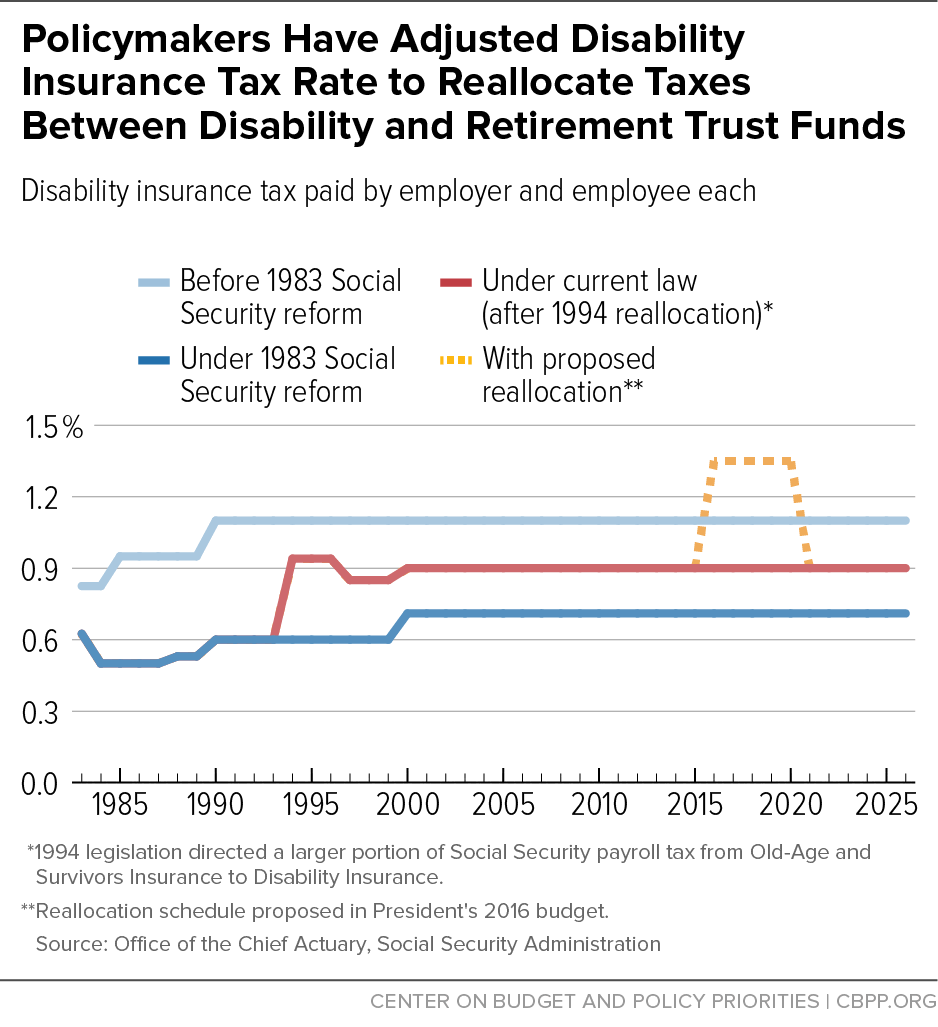

A separate disability fund isn’t fiscally necessary — merging the funds is a sensible and longstanding idea — but Congress has instead simply rebalanced taxes between the funds as needed, with strong bipartisan majorities and without controversy.[3] Lawmakers have done so many times, and reallocations have gone in both directions.[4]

The last two reallocations shortchanged DI. In 1983, with DI in relatively strong financial shape but OASI close to insolvency, Congress cut DI’s share of the payroll tax significantly while boosting OASI’s share. Congress only partly reversed that shift in 1994. At that time, the trustees projected that the DI trust fund would be exhausted in 2016 and the OASI fund in 2031. Current estimates confirm these projections: policymakers will need to replenish the DI fund by late 2016, while the OASI fund is solvent through 2035.[5] If DI’s tax rate had remained at its pre-1983 level, we would not need to rebalance again today. (See Figure 1.)

Some have argued that Congress premised the 1994 legislation on the future adoption of unspecified DI reforms, but that is not correct. Although Social Security’s two public trustees called for changes to DI, the Board of Trustees as a whole did not, and the 1994 law itself required only that the Social Security Administration conduct a study of the reasons for rising DI costs.[6] The results of this effort were published in 1995.[7]

The one time policymakers adopted interfund borrowing, over 30 years ago, they did so only as a short-term stopgap. In the early 1980s, Social Security’s retirement fund faced imminent insolvency, and policymakers took the opportunity to enact reforms to address the program’s overall solvency.

First, Congress temporarily rebalanced funds between the programs. In 1980, by unanimous votes in both chambers, it temporarily reallocated tax revenue from DI to OASI.[8] Still, further action was needed to enable OASI to pay full benefits in 1982. To avoid an abrupt cut, Congress permitted the OASI fund to borrow from the DI and Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust funds.[9] The Secretary of the Treasury transferred money to the OASI fund in several installments in 1982.

Next, policymakers took steps to put Social Security on a stronger financial footing for the long term. On the same day that Congress approved the initial law allowing Social Security to borrow between funds, President Reagan issued an executive order establishing a Social Security reform commission.[10] Speaker Tip O’Neill, President Reagan, and pragmatists from both parties crafted a bipartisan deal that improved Social Security’s solvency through tax increases, benefit reductions, and other changes.[11] As noted above, that package also reallocated a significant share of the payroll tax from DI to OASI — which, in retrospect, contributed greatly to DI’s subsequent shortfall. President Reagan signed the package into law in 1983, and the OASI fund — now with enhanced tax revenues and savings from a delay in the annual cost-of-living adjustment — was able to repay all borrowing, with interest, by 1986.

In sum, policymakers in the 1980s clearly linked interfund borrowing to development of a concrete, bipartisan plan to repay the debt and strengthen Social Security for the long term. No such connection exists now.

DI’s shortfall — and Social Security’s more generally — can only be addressed in two ways: higher revenues or lower spending. Advocates of interfund borrowing have proposed nothing that would raise revenues or cut benefits enough to repay a loan or fix DI’s shortfall for the long term.[12] And they have implicitly ruled out any solutions in which revenues would play a part — even rebalancing, which would not affect anyone’s paycheck.

Some proponents of interfund borrowing assert that in a few years, when the loan would come due, policymakers can make significant changes in DI to repay the loan. But it’s far from clear what such changes would be. Policymakers shouldn’t count on demonstration projects yielding useful results that point the way to measures to shrink DI enough to repay the loan and restore solvency without harming very vulnerable people. Designing, conducting, and securing reliable results from demonstration projects takes time and can’t be done quickly. Moreover, the Social Security Administration has undertaken a number of demonstration projects over the years to test new ways to encourage DI beneficiaries to return to work, and they have either produced only limited results or not proved cost-effective, rather than pointing the way to measures that yield large savings without harming vulnerable individuals with serious disabilities.[13] It’s worth testing promising changes to DI through carefully designed demonstration projects. But policymakers shouldn’t expect those to yield quick answers or large savings.

Requiring the DI trust fund to borrow may also set the stage for deep cuts in DI later. Extending a loan with no repayment mechanism simply digs a deeper hole and invites harsh changes in DI a few years down the road when headlines trumpet DI’s “massive debt.” Moreover, this would risk encouraging policymakers to tackle DI in isolation — which likely would necessitate focusing on unduly harsh options and ignoring the strong interactions between the eligibility and benefit structures of Social Security’s disability and retirement components — rather than addressing the insolvency of Social Security as a whole.

Shifting a small portion of the payroll tax to DI would avert a sudden benefit cut of nearly 20 percent and have only a tiny effect on OASI’s solvency (shifting its insolvency date from 2035 to 2034), giving policymakers time to focus on strengthening Social Security as a whole without creating an artificial deadline or setting DI up for potentially damaging changes. Social Security’s disability, retirement, and survivor programs are closely linked, and Congress should consider substantive changes to DI only as part of a comprehensive package that puts all of Social Security on a stable financial footing.