Researchers and policymakers have begun to examine the role that private disability insurance (PDI) might play in helping workers with chronic conditions and severe impairments remain at or return to work. This examination, which focuses on private long-term disability insurance (PLTDI), has arisen in large part as a result of the projected depletion of the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund in late 2016.[1] This paper focuses on a proposal to allow employers to enroll workers automatically into PLTDI policies, at the worker’s own expense, unless the worker opts out.[2]

The automatic enrollment proposal, advanced primarily by the insurance carrier Unum, has two main components. First, it would allow any employer covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act to automatically enroll its employees into PDI coverage, provided the employee receives notice and an opportunity to opt out. Federal law would supersede state payroll withholding laws prohibiting this type of auto-enrollment arrangement for PDI. The proposal includes no minimum benefit requirements — for example, income replacement amounts or length of coverage — for the PDI plans into which employees would be enrolled, or any specific requirements for what the notices regarding auto-enrollment must include. Second, the proposal would establish a national clearinghouse to provide information regarding the risks of acquiring a work-limiting disability, help individuals make the decision about whether to purchase PDI coverage, and assist employers in making the decision about whether to purchase or sponsor PDI coverage and if so how to design the PDI plan.[3]

Although on its face the proposal seems modest, it raises significant questions regarding the value of these policies to the workers who would be auto-enrolled. In addition, the failure to include benefit requirements and consumer protections regarding auto-enrollment notices is a serious omission, as these should accompany any authority given to employers to auto-enroll workers in PDI or to expand PDI coverage more generally.

Providing income replacement and services and supports to help individuals stay at or return to work when they acquire a disability due to an accident or illness, or when an existing condition worsens, is a laudable goal. But allowing automatic enrollment to expand coverage to workers who have not traditionally been covered by PDI merits careful examination to ensure that the workers being auto-enrolled are receiving added value for the additional premiums they will pay. Nearly all workers already pay Social Security payroll taxes for income replacement insurance through the SSDI program. Any expansion of PDI should ensure that the individual’s economic security is increased through additional coverage beyond what SSDI provides and that the coverage provides access to effective return-to-work services appropriate to the employee’s skills and the industry in which he or she works.

Significant questions exist as to whether PDI will be able to assist newly covered workers to the same extent it assists workers currently covered due to differences in the characteristics of both the workers and the types of jobs they have. It is unclear whether the return-to-work services currently provided through PDI policies will be appropriate and effective for individuals in different types of jobs or employment situations (for example, part-time workers) as coverage is expanded. Significant uncertainty also exists as to whether and to what extent PDI coverage makes sense for workers who lack comprehensive benefit packages and whether auto-enrollment might reach those workers. As a result of these uncertainties, any legislation that gives an employer explicit auto-enrollment authority that overrides state laws forbidding wage withholding without express written consent should contain minimum benefit requirements and consumer protections to ensure that the coverage enhances the economic security of workers and increases the likelihood of continued attachment to the workforce.

PDI provides a partial replacement of income when an insured individual can no longer do his or her job due to a disabling condition. Although individuals can purchase PDI, this paper examines only employer-sponsored group policies, as those are the focus of the auto-enrollment proposal. There are two primary types of PDI: short term (PSTDI) and long term (PLTDI). However, because PLTDI has a greater potential to impact SSDI enrollment and spending, only PLTDI is usually referenced when discussing auto-enrollment, and this paper will focus on that.

Long-term disability insurance provides income replacement to insured workers whose illness or injury precludes work for an extended period, usually six months or more. A typical PLTDI plan provides income replacement of 60 percent of pre-injury or illness earnings, though approximately one in four policies currently in place provide less than that amount for workers who become disabled.[4]

PLTDI companies also provide beneficiaries with return-to-work or stay-at-work services. For an individual who appears likely to be able to resume working, the insurance company will provide services such as coordination of health care and vocational services (note though that companies do not generally cover the services themselves), negotiations of job accommodations (such as ergonomic work stations, part-time schedules, or transfers to different positions), job placement services, resume development, and job skills training.[5]

Definition of disability: In order to receive benefits, an individual must meet the definition of disability contained in the insurance policy. Policies have different requirements to determine whether an insured individual is eligible for benefits. Some require only that the individual not be able to do his or her own job (own/regular occupation), whereas some require that the individual be unable to perform any job (any gainful occupation). Many policies will pay benefits for being unable to do one’s own job for a certain period of time (two years is common) and then require the beneficiary to be unable to do any job to continue to receive benefits. Some pay partial benefits when an individual can work only part time and the person’s income has been reduced by a certain percentage as a result of the disability.

Waiting (elimination) period: A person must wait after an illness or injury and be unable to work for a certain period before benefits are payable. The typical waiting period is six months (180 days), but it can range from a few months to up to 365 days.

Benefit period: PLTDI policies may limit the amount of time for which an individual can receive benefits. Policies can vary significantly in this regard, with some offering lifetime benefits and some offering them for a set number of years (sometimes as few as two or five). Many policies pay benefits up to age 65 or the individual’s retirement age. It is not uncommon for benefit periods arising from mental health conditions to be significantly shorter (typically limited to 24 months) than those arising from physical conditions.[7]

Preexisting condition coverage limitations: PLTDI can have restrictions on coverage for preexisting conditions. For employer-sponsored group plans, coverage cannot be denied to someone who enrolls in the group plan during the initial enrollment period. However, the policy can include an exclusionary period, usually one to two years, in which there is no coverage for a preexisting condition.

Benefit offsets: All PLTDI policies include provisions that reduce the amount of the benefit if the beneficiary receives income support based on his or her disability from another source, and some reduce benefits from any income, disability related or not. Almost all PLTDI plans include a required offset for SSDI benefits, and require a beneficiary to apply if the company believes the PLTDI beneficiary is eligible for SSDI benefits. Other income benefits that can offset PLTDI benefits include workers’ compensation payments, pension payments, SSDI dependent benefits, rollovers of lump-sum payments from defined-benefit or defined-contribution plans, and veterans’ benefits.

Inflation protection: For a higher premium, PLTDI policies may include protections against inflation in the form of cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs.

Rehabilitation: Some PLTDI policies contain clauses that specify the amount, if any, the insurance company will pay for physical or vocational rehabilitation to assist the individual to stay at work or return to work.

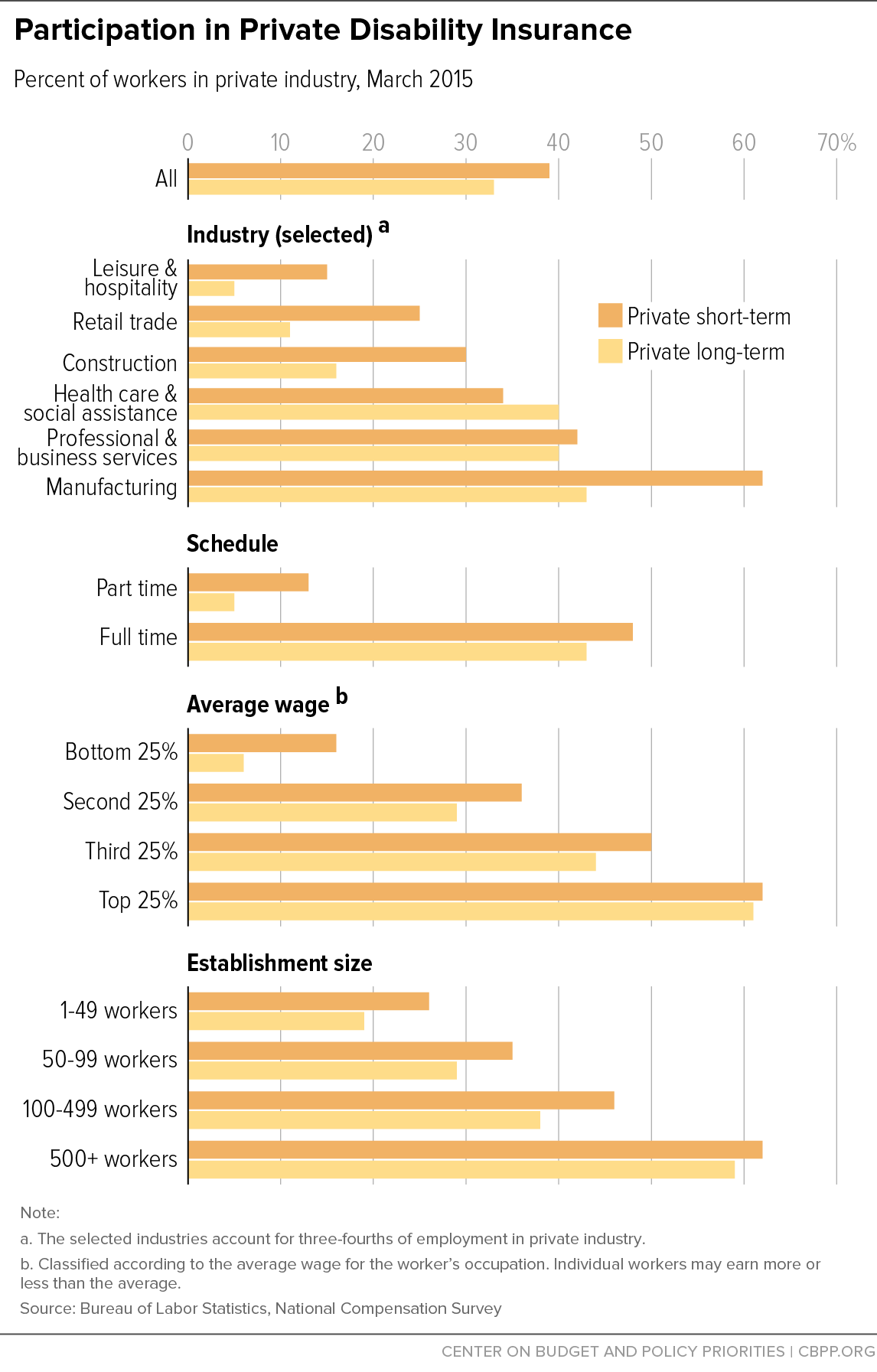

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), approximately 33 percent of workers in private industry had PTLDI coverage in 2015.[8] The percentage of workers covered, however, varies significantly depending on the type of work, earnings, and full-time or part-time status. (See Figure 1.) Coverage is much higher, for example, in skilled, white-collar occupations. The top quartile of earners have coverage at rates ten times higher than the bottom quartile, and the top 10 percent of earners (not shown in figure) have coverage at rates more than 30 times higher than the bottom 10 percent. Only one in 20 part-time workers has coverage, compared to over four in ten full-time workers. Only about one in 20 workers in the leisure and hospitality sector currently has PLTDI coverage, while more than four in ten workers in the manufacturing and professional and business services sectors do.

A PSTDI policy is designed to provide income replacement when a disabling impairment precludes work for a limited time. Short-term policies have many of the same features as PLTDI policies. Benefit payments generally begin after an individual has used his or her paid sick leave, if any,[9] and consist of a percentage of pre-disability income (most commonly 60 percent but amounts can vary significantly by policy)[10] when the individual can no longer work, or can work only part time under some policies, due to a work-disabling condition.[11] PSTDI pays benefits for between nine and 52 weeks, with the standard benefit length being 26 weeks.[12] Elimination periods generally range from zero to 30 days; the industry standard is seven.[13]

Thirty-nine percent of all workers employed in private industry were covered by employer-sponsored PSTDI in 2015.[14] As with PLTDI (see Figure 1), coverage levels vary based on the worker and industry characteristics and are higher for full-time workers, higher earners, and workers employed with larger employers or in skilled occupations. In addition to PSTDI, five states and Puerto Rico have public social insurance programs that provide temporary partial wage replacement for workers unable to perform their normal work due to disability.[15]

It is not possible to tell from the publicly available BLS data whether the same individuals have PSTDI and PLTDI. Because the percentage of workers who have PSTDI is generally similar to or greater than those who have PLTDI, and because insurers typically integrate the two types of coverage, it is reasonable to assume that most workers who have PLTDI also receive employer-paid PSTDI as part of a comprehensive benefits package.

The model used by PDI has evolved based on the types of workers covered, the relationship between covered employees and their employers, and the nature of the industry and the workplace. The types of services provided to workers to get them back to work have also evolved to meet the specific demands of the industries and work environments of plan participants. Many questions arise regarding whether the existing model will provide value and be effective with different types of workers, in different industries, and different work environments.

As detailed in Figure 1 and discussed in the previous section, most of the workers currently covered by PLTDI are in higher-paid, skilled jobs that tend to require higher levels of educational attainment. The BLS data do not break down coverage levels by educational attainment or age, but data are available regarding both of these and other characteristics of SSDI beneficiaries. SSDI beneficiaries have lower educational attainment than the general public, with somewhere between 50 and 64 percent of beneficiaries having a high school diploma or less and fewer than one in five having completed a post-secondary degree.[16] In contrast, about 40 percent of all adults have a high school education or less. People receiving SSDI are also more likely than the average worker to have been in unskilled or low-skilled jobs prior to becoming eligible for benefits (nearly 70 percent reported working in manual-labor, retail, or service jobs);[17] nearly half work in service industries.[18] The majority of SSDI beneficiaries are also older: 70 percent are over age 50, 50 percent are over age 55, and 30 percent are over 60.[19]

Virtually all PLTDI policies require an individual to apply for SSDI benefits as soon as the insurance company is fairly certain that the individual will be determined eligible.[20] According to a report commissioned by America’s Health Insurance Plans, approximately 72 percent of workers who receive PLTDI benefits also end up receiving SSDI benefits.[21] Because of the requirement in plans for people receiving PLTDI benefits to apply for SSDI benefits and the less stringent definition of disability in most PLTDI plans, at least initially (the inability to do one’s own occupation versus the SSDI requirement than an individual be unable to do any job that exists in the national economy in sufficient numbers), it is unclear whether, or to what extent, PLTDI deters or delays any workers from applying for or receiving SSDI. The only way to be certain that a particular worker’s impairment meets the SSDI definition of disability is for the individual to apply for SSDI and be found eligible by the Social Security Administration for benefits. Due to nearly universal SSDI offsets, PDI carriers have strong financial incentives to assist anyone who might be eligible for SSDI to apply. Although the insurance industry argues that PDI coverage results in substantial reductions in SSDI expenditures, it is difficult to identify how any worker receiving PDI benefits who might be found eligible for SSDI would delay or avoid SSDI application given these plan requirements and financial incentives.[22] In addition, if the application is delayed but the person eventually applies for SSDI benefits and is approved, there may be no or limited savings to SSDI because SSDI benefits are retroactive for up to 12 months after the date of the completion of the SSDI five-month waiting period.

In fact, expanding private disability insurance coverage might actually increase the cost of SSDI. Higher long-term benefit levels would potentially induce more disabled workers to apply for benefits. And the provision of short-term disability benefits might make it easier for disabled workers to get through SSDI’s five-month waiting period.

PLTDI policies provide two basic benefits to plan participants who file a claim and meet the eligibility requirements. The first is income replacement, and the second is services to assist the individual in staying at or getting back to work. Significant questions exist as to whether the stay-at-work and return-to-work services provided by PLTDI to educated, skilled, highly paid salaried workers will be effective for the low-skilled, lower-wage (often hourly) workers in blue-collar, retail, and service occupations who are more likely to apply for and eventually receive SSDI benefits. Available data do not disaggregate the professions or characteristics of workers or the types of industries or work environments for which particular services are effective. Also, it is unclear whether and to what extent medical improvement plays a role in returning individuals to work rather than the provision of services by PLTDI carriers.

As detailed above, the primary services that PLTDI insurance providers offer to help individuals remain at their jobs or go back to their own or another job include things like purchasing ergonomic desks, coordinating with and supplementing commercial health care insurance, negotiating with employers for flexible or alternative schedules, working with the employer to move the employee to a part-time schedule, eliminating duties requiring lifting, or placing the employee in another job in the same company. The flexibility an employer has to offer these types of equipment and job accommodations is in no small part determined by the nature of the employer’s business, the size of the employer, and the types of jobs and schedules available.

Given the differences in characteristics of SSDI beneficiaries and workers currently covered by PLTDI, it is likely that these services will not be appropriate or effective for many newly covered individuals. For example, reducing hours might not be possible for someone already working part time. It is also not clear how the services offered by PLTDI companies could assist a worker who can no longer stand for long periods or lift objects over a certain weight if that individual works at a company where all jobs require physical labor. Many jobs in the service and retail sectors lack any flexibility in terms of scheduling and tasks. Employer size might also limit the effectiveness of services. Large employers are likely to be able to accommodate workers more easily than small and medium-sized firms, both in terms of possible alternate jobs and alternate schedules. Questions regarding the effectiveness of services are amplified for older workers with a high school diploma or less.

The services provided by PLTDI may also not be as effective in helping individuals with significant mental health conditions return to or stay at work. Many of the services commonly provided, such as rehabilitation, ergonomic furniture, reduced hours, and elimination of physical duties, appear to be most effective in assisting individuals dealing with physical impairments or fatigue and lack of strength. Additional information beyond what is publicly available would be needed to understand how the services typically provided by PLTDI companies would assist individuals with mental impairments in staying at or returning to work. As noted, many policies contain benefit period limitations on coverage for mental health conditions, and therefore insurers might have less incentive to provide expensive or difficult return-to-work or stay-at-work services to individuals with mental impairments. In fact, the most successful approaches for assisting people with a mental illness that meets the SSDI definition of disability involve the provision of ongoing supports with no time limits, not a model PDI carriers are likely to be willing to follow due to the ongoing commitment and cost.[23]

These questions regarding both the appropriateness and effectiveness of the return-to-work services offered by PDI carriers to individuals who might be auto-enrolled into PDI policies need further evaluation. If these services will not help the newly covered workers remain in or return to their jobs due to the nature of their disability or their industry or work environment, then federal action to override state laws to allow auto-enrollment might not be warranted, especially if there are questions about the adequacy of the income replacement benefits (discussed later in this paper).

PLTDI offered to employees and paid for by employers has traditionally been a component of a comprehensive benefit package designed to attract skilled workers. Those packages usually include other benefits such as health insurance, life insurance, short-term disability insurance, paid leave including sick and vacation leave, and access to retirement plans. Expanding coverage to workers who do not have employer-sponsored comprehensive benefit packages might not make sense unless accompanied by benefit and policy requirements.

For example, it is not clear how PLTDI services might assist individuals who do not have health insurance coverage. PLTDI does not provide basic health coverage, and, despite the enactment of the Affordable Care Act, fewer than one in four part-time workers have access to health insurance through their employer, and only about one in seven participate.[24] Workers in the bottom 10 percent of earners have access and participation at approximately the same rates as part-time workers.[25] According to the most recent National Health Interview Survey, one in seven employed adults lacked any health insurance coverage in 2014.[26] It seems unlikely that health care coordination or the other stay-at-work or return-to-work services could be effective for those workers who lack health insurance or the ability to pay for their needed health care.

Furthermore, PLTDI insurance coverage requires an individual to be unable to work for a certain period of time before he or she becomes eligible for benefits, usually a minimum of six months but sometimes more. This elimination period is likely to pose a hardship for workers who do not have access to paid leave. Thirty-nine percent of all workers have no paid sick leave, and nearly one in four workers have no paid vacation. For part-time workers the shares are higher: three-quarters have no paid sick leave and just under two-thirds have no paid vacation. Among the lowest 25 percent of earners, more than two-thirds lack paid sick leave and more than half lack paid vacation.[27] An eligible worker who works for a covered employer is entitled to up to 12 weeks of job-protected unpaid leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), but that leaves the individual without income during that time.[28] Additionally, approximately 40 percent of workers are not even entitled to take unpaid FMLA leave because they don’t work for covered employers (that is, the employer has fewer than 50 employees) or they are not eligible employees (that is, they worked for their employer less than a year or worked less than an average of 24 hours per week).[29]

It is unclear whether, and if so for how long, an individual who is lower income and without paid sick or vacation leave would be able to keep paying his or her disability insurance premiums after becoming ill or being injured. Often ill or injured individuals reduce their hours prior to leaving work. Some individuals who work more than one part-time job might quit one job and continue to work another but have significantly reduced income. If an individual reduced hours and was struggling to make ends meet, he or she might be unable to continue to pay the PLTDI premium, even if still working. Combined with the fact that most low- to moderate-income households lack any savings,[30] let alone enough to pay for necessities for six months, this raises a significant question of how many currently uninsured workers would be able to maintain their insured status after an illness or injury when they have reduced their hours or separated from their employer during the elimination period.

PSTDI might be helpful in such a scenario (and is what most currently insured workers would rely on after exhausting paid leave), but that is also unclear. Although the proposal to allow auto-enrollment could authorize enrollment in both short- and long-term policies, it is probable that many workers would drop one or the other due to cost. Thus, serious consideration needs to be given to how newly covered workers who lack paid leave and health care coverage would maintain insured status.

Most PLTDI plans replace 60 percent of the insured’s pre-disability income, with one in four plans replacing less than 60 percent. For high earners, 60 percent generally exceeds what they would receive if they met the SSDI definition of disability and applied for and received benefits (SSDI benefits replace about 45 percent of lifetime pre-disability earnings for the average earner and as little as 29 percent for workers who consistently earned the taxable maximum, which is $118,500 for 2015. Workers with earnings above the taxable maximum have lower replacement rates).[31] However, low and medium earners often get more than 60 percent of their pre-disability income replaced by SSDI, especially when dependent benefits are included.[32] A full-time worker earning the minimum wage, for example, would receive about 67 percent of his or her pre-disability earnings if eligible for SSDI, even higher if the worker had dependents and received the maximum family benefit (approximately 85 percent).[33]

These facts regarding replacement rates suggest that, from a purely economic security perspective, for low and moderate earners PLTDI does not necessarily provide any income support above what they are already eligible to receive and pay for through SSDI. In light of almost universal SSDI offsets, low- and moderate-income individuals might be paying twice for no increase in economic security, especially when SSDI dependent benefits are included in offsets.

III. Benefit Requirements and Consumer Protections Needed

for Automatic Enrollment

Most states have laws that prohibit employers from withholding any money from an employee’s earnings without express written consent from the employee.[34] This is an important protection for employees, and federal law rarely overrides state laws prohibiting this practice. Such an arrangement was allowed for 401(k) retirement plans, but those plans must meet very specific requirements, including an employer contribution in certain amounts under certain circumstances.[35] Ensuring that the PLTDI policies into which employees could be auto-enrolled meet basic requirements similar to those applied to 401(k)s would be particularly important given the fact that the money invested in a 401(k) continues to belong to the individual should he or she choose to discontinue contributions or move to another job. The same cannot be said for premiums paid to a PDI company: there is no residual value nor portability of the insurance policy. If an auto-enrollment arrangement for PDI is pursued, policymakers should enact (or require to be specified in regulation, with specific guidance as to the nature of the regulations) corresponding consumer protections that include minimum plan and notice requirements.

PLTDI, like most insurance products, is primarily regulated at the state level.[36] Employer-sponsored PLTDI, which is currently paid for entirely by the employer for 94 percent of plan participants, is governed by ERISA, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. ERISA and its implementing regulations set out basic requirements for plan documents and disclosures[37] as well as basic requirements for notices and appeal procedures.[38] However, there is significant concern that the current ERISA consumer protections in the areas of plan disclosures, claims procedures, and remedies as they relate to disability insurance are inadequate and should be addressed if coverage is expanded. This is especially true if ERISA preempted state payroll withholding laws prohibiting automatic enrollment in employee-paid PDI plans.

ERISA provides basic federal protections that govern all employer-sponsored retirement and employee welfare benefit plans. It has specific requirements regarding what has to be included in plan summaries related to benefits offered, for example, but provides only that “a general description of such benefits is required if reference is made to detailed schedules of benefits which are available without cost to any participant or beneficiary who so requests.”[39] The regulations also require the plan summaries to include “a statement clearly identifying circumstances which may result in disqualification, ineligibility, or denial, loss, forfeiture, suspension, offset, reduction, or recovery.…”[40]

The ERISA Advisory Council, an appointed body of employee organization representatives, employers, insurance industry representatives, and other experts in the field of employee benefits and ERISA, recently examined the sufficiency of ERISA disclosure requirements in the context of PDI policies.[41] Despite the requirements outlined above, the council found that “[t]he complex nature of many disability coverage contracts and the administration of these contracts have often resulted in the insured, and sometimes the sponsoring employer, misunderstanding the details of the coverage and the true nature of the benefits that are due when a disability occurs.”[42] This especially appears to be the case regarding potential benefit offsets and the impact that these offsets have on the benefit the individual receives.[43]

Potential Plan and Benefit Requirements

Because of the serious questions raised here regarding the value of PLTDI to many workers who might be auto-enrolled, any federal statute that allows employers to institute automatic enrollment arrangements for PDI superseding state withholding laws should include requirements that the policies provide value to the insured worker. In addition, any legislation should specifically mandate that any PDI plan offered through an automatic enrollment arrangement is an ERISA-covered benefit plan irrespective of whether there is any financial contribution by the employer for the coverage. If this expansion is voluntary (meaning employers may but are not obligated to offer it to their employees) but designed to delay or avoid SSDI eligibility, it is important that the specific features of the insurance policy contribute to that goal. Among the features that policymakers ought to consider requiring in order to maximize the early intervention potential of PLTDI are:

- Own-occupation coverage: As noted above, some PLTDI policies specify that an individual be unable to do his or her own job to receive benefit payments, while some require that the individual be unable to do any job based on his or her education and experience (similar to the SSDI definition of disability). If delaying or avoiding SSDI benefit receipt is a justification for allowing auto-enrollment, then policies offered through auto-enrollment should provide broader coverage than SSDI to maximize the chances that PLTDI will assist the individual in staying attached to the labor force. It might be wise to require own-occupation coverage for at least 24 months, the standard period in many policies and the period during which most recoveries happen.

- Short elimination period: If one goal of auto-enrollment is to assist workers in maintaining their workforce attachment after onset of disability, ensuring that insured individuals get access to income replacement benefits as quickly as possible would seem to be an important consideration. As mentioned, elimination periods are typically six months but can be longer. SSDI has a five-month waiting period from the onset of the disability. If PLTDI’s elimination period were longer, that might decrease the chances that PLTDI will function as an effective early intervention program. Requiring a short elimination period could contribute to making PLTDI more effective in delaying or preventing a plan participant from applying for SSDI.

- Return-to-work services: If one goal of allowing auto-enrollment in PDI is to help more individuals stay at or return to work, it makes sense to require those policies to provide a robust array of services. Requiring PDI carriers to pay for all needed rehabilitation — physical, occupational, and vocational — without placing a monetary cap on the amount of services, equipment, or training the policy will provide would be one way to accomplish that.

- Minimum income replacement percentage: Policymakers should consider requiring a minimum percentage of wage replacement in policies offered though auto-enrollment arrangements, especially because this coverage expansion will likely include low- and moderate-income workers who receive higher replacement rates from SSDI. Another possible approach would be to limit auto-enrollment to those classes or types of employees for which PLTDI provides income replacement rates above what an individual would receive if eligible for SSDI. Such a limitation would likely exclude any worker earning below the median wage.

- Restrictions on offsetting PLTDI payments when SSDI eligible: Almost all PLTDI policies require an individual to apply for SSDI benefits as soon as the insurance company is fairly certain that the individual would be determined eligible. PLTDI benefits are then offset dollar for dollar by the amount of the SSDI benefit, and in many cases so are dependent and spousal benefits.[44] The SSDI offset is thought to be important for keeping premiums and costs down.[45] However, the existence of the offset might also discourage companies from providing a full array of return-to-work services because it might be cheaper to pay benefits with the offset than to pay for expensive accommodations, rehabilitation, or training. This potential incentive created by the SSDI offset for PLTDI companies could significantly limit the effectiveness of PLTDI as an early intervention program for SSDI. A number of approaches could be taken to limit the impact this offset has on PLTDI effectiveness as an early intervention program; these include prohibiting the offset for a certain time period of benefit receipt, limiting the percentage of the PLTDI payment that can be offset by an SSDI benefit, and/or prohibiting an offset for Social Security dependent benefits.

- Mental health parity: If auto-enrollment is contemplated as an early intervention strategy to provide workers with support that would delay or avoid SSDI application, the current limitation on benefit terms for people with mental illness should be examined. A significant portion of SSDI beneficiaries receive benefits on the basis of having a mental health impairment,[46] especially newly awarded SSDI beneficiaries who begin receiving benefits under age 50.[47] Federal law generally prohibits commercial health insurance policies from imposing less-favorable benefit limitations for mental health services than for medical or surgical benefits.[48] A similar requirement for parity in coverage for mental and physical impairments in PDI should be considered if auto-enrollment is allowed.

- Preexisting condition limitations: Preexisting condition limitations (complete exclusions and time-limited ones) run counter to the purpose of maximizing PDI’s value as an early intervention program. This problem could be addressed by a number of different requirements, such as prohibiting any exclusion of coverage for a preexisting condition when an employee purchases coverage during the employee’s initial enrollment period, and limiting the amount of time for which a company could exclude coverage for a preexisting condition.

- Continuation of insured status: Low or moderate earners might find it difficult to continue paying a premium as their disability worsens. Some individuals might have to reduce hours due to an accident or illness and might not be able to continue to pay premiums due to the reduced income. If coverage is expanded to workers who might lack either paid leave or the savings to cover expenses during a time of reduced hours or unemployment, it would make sense to include requirements on insurance companies related to continuation of insured status for individuals unable to pay premiums due to reduced income brought on by their disabling condition. Otherwise, workers who lack comprehensive benefit packages might pay for coverage of which they would never be able to take advantage, as it is highly unlikely they would be able to continue to pay premiums if they reduced their hours or quit a part-time job and earned substantially less.

As with all insurance products, premium costs for PDI are directly related to the generosity of the policy. The larger the percentage of income replaced, the shorter the elimination period, the fewer offsets, or the more generous the rehabilitation benefit, the higher the premium will be. Determining which of these plan requirements ought to be included and the impact they have on the premium cost requires actuarial and other calculations that are beyond the scope of this paper. Policymakers will have to consider carefully the proper balance of policy requirements and premium cost before proceeding to authorize auto-enrollment, especially because the employee will be paying the premium in an auto-enrollment arrangement. The premium cost must be kept low to encourage low- and moderate-wage workers not to opt out of coverage, but the benefits must be robust, both in terms of income replacement and services provided, in order for the policy to provide value. Low- and moderate-income workers must receive robust benefits, not only because SSDI replacement rates for such workers are generally more than 50 percent, but also because these workers may be less likely to be able to benefit from stay-at-work and return-to-work services.

The issues and shortcomings identified at the ERISA Advisory Council hearings regarding the current ERISA statutory and regulatory protections for individuals as they relate to disability insurance provided through employment relationships should be addressed before any federal action to expand PLTDI is taken. Any legislation that would allow auto-enrollment should strengthen the notice and disclosure requirements under ERISA as they relate to disability insurance.

Plan documents and benefit summaries for plans in which employers can auto-enroll their employees should be required to provide detailed information in plain language regarding plan designs, features, offsets, and excluded conditions. At the very least, rules should require plan summaries to clearly state all income sources that would result in an offset to the benefit and the extent of that offset, the percentage of pre-disability income the benefits replace, the degree to which plan income supplements the individual’s SSDI benefit or is offset entirely by it, any preexisting condition limitations, mental health coverage benefit term limitations, and the duration of those exclusions or limitations.

Assisting individuals with disabilities to maintain or regain workforce attachment and improving their economic security by providing additional wage replacement are laudable goals. All workers and their employers already pay for wage replacement insurance through payroll tax contributions to the Social Security Disability Insurance program. PLTDI can provide additional income support and services to assist individuals to stay at work or return to work. The PLTDI insurance model works well with salaried, skilled, well-paid workers, but serious questions exist whether and to what extent the same advantages will accrue to the types of additional workers who might be enrolled into PDI policies as a result of an auto-enrollment process.

Allowing employers to withhold wages from employees without express written consent from the employee is an extraordinary measure that is prohibited in most states. When Congress has overridden state withholding laws in the past, as with 401(k) plans, it has done so only with specific plan requirements, as well as consumer protections, for the products into which employees may be auto-enrolled. Unlike with 401(k)s, where the money invested is retained by employees even if they choose to end the arrangement, significant questions exist regarding the value of PDI to many workers. It would therefore be prudent to complete additional study before moving forward with expansion of PLTDI (possibly in the form of pilots or demonstrations) through an auto-enrollment arrangement. Any authority given to employers to auto-enroll workers in PDI should be accompanied by plan requirements and consumer protections to ensure that the coverage is of value to the employee. The requirements should ensure that the PDI policies remain affordable but also provide value to the worker, both in terms of enhanced economic security and services to assist the individual to remain at work.