A groundbreaking new study by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) demonstrates that Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) — tax-favored savings accounts attached to high-deductible health insurance plans established under the 2003 Medicare drug law — are heavily skewed toward affluent individuals. The GAO findings also provide strong indications that HSAs are being used extensively as tax shelters. Finally, the GAO data suggest that HSAs can be beneficial to healthy individuals with relatively few health care costs, but not to people who have medical conditions and incur higher costs.

Many health and tax policy analysts have warned in recent years that HSAs are likely to be used extensively as tax shelters by high-income individuals. The Administration and other HSA proponents have rejected such concerns and argued that HSAs are not disproportionately used by high-income households. ;

Until recently, though, little or no solid data have been available to assess whether HSAs are — or are not — being used disproportionately by affluent individuals. The primary data available have been on enrollment in HSA-eligible high-deductible plans in the small, individual health insurance market, which is skewed toward people at low and moderate income levels who cannot get employer-based coverage. Such data shed little light on HSA use in employer-based insurance, where the vast bulk of Americans obtain their coverage.[1] Moreover, such data do not appropriately distinguish between individuals enrolled in a HSA-eligible plan who are merely qualified to establish a HSA and the more limited number of individuals who have actually opened and are using HSAs.[2] ;

Now, this has changed. An important GAO study issued earlier this month breaks new ground, by providing data from the Internal Revenue Service on who actually is using HSAs.[3] The IRS data cover all Americans who made HSA contributions in 2004, regardless of whether they had individual or employer-based coverage.[4] The GAO study also contains data, from three large employers who offer both HSA-eligible plans and traditional coverage, on how their employees have sorted themselves between HSA-eligible coverage and traditional insurance.

The GAO supplemented these data by conducting focus groups of individuals at these three firms who selected HSA-eligible plans, as well as individuals at these firms who opted for traditional coverage. The GAO also reviewed data on enrollment in HSA-eligible plans from several national surveys of employers. ;

The GAO data represent the first solid, broad-based data on actual HSA use by income. Accordingly, they are now the premier data in the field to determine whether HSAs are being disproportionately used by high-income households. ;

The principal findings in the GAO report include the following.

- 51 percent of tax filers making HSA contributions in tax year 2004 (the first year HSAs were available) had adjusted gross income of $75,000 or more. This represents a decisive skewing toward higher-income individuals, since only 18 percent of all tax filers under age 65 had incomes of $75,000 or more in 2004.

- The average adjusted gross income of tax filers reporting HSA contributions in 2004 was $133,000, as compared to $51,000 for all tax filers under age 65 in 2004.

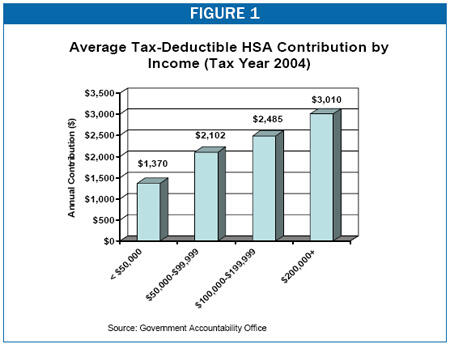

- In addition to making much greater use of HSAs, higher-income individuals also make larger tax-deductible contributions to HSAs. HSA participants who had incomes over $200,000 contributed an average of $3,010 in 2004. This was more than double the average contribution of $1,370 for HSA participants who had incomes below $50,000. This difference in average contribution levels further skews the tax benefits of HSAs to households that are high on the income scale.

- About 55 percent of tax filers reporting HSA contributions in 2004 did not withdraw any funds from their accounts and “appeared to use their HSA as a savings vehicle.”

- HSA participants in the focus groups that the GAO conducted “reported using their HSA as a tax-advantaged savings vehicle, accumulating HSA funds for future use.”

- The GAO reported that when individuals are given a choice between HSA plans and more traditional health insurance plans, HSA plans are attracting “higher-income individuals with the means to pay higher deductibles and the desire to accrue tax-free savings.”

HSAs and High Deductible Plans Reduce Costs for the Healthy, But Raise Them for the Less Healthy

- The GAO analyzed the total out-of-pocket costs — premiums, deductibles, and co-payments combined —- that would be incurred under the traditional coverage and high-deductible plans tied to HSAs offered by three large employers. The GAO found that healthy enrollees who use little health care would tend to incur lower costs under the HSA-eligible plans than under the traditional plans offered by the employers, while people who use more extensive health care services would tend to incur higher costs under the HSA plans.

- This reality was reflected in the focus groups. Most HSA-eligible plan participants in the focus groups were satisfied with their plans and said they would recommend HSA-eligible plans to healthy people. But they would not recommend such plans, the GAO reported, “to those who use maintenance medication, a chronic condition, have children, or may not have the funds to meet the high deductible.

- For these reasons, the GAO essentially included a warning in the report that HSAs may lead to the separation of healthy and less-healthy individuals into separate insurance arrangements. The GAO concluded: “… when individuals are given a choice between HSA-eligible and traditional plans — as in the individual market and with employers offering multiple health plans — HSA-eligible plans may attract healthier individuals who use less health care or, as we found, higher-income individuals with the means to pay higher deductibles and the desire to accrue tax-free savings.” Health policy experts have long counseled that policymakers should seek to avoid the separation of healthier and less-healthy people into separate insurance arrangements; when less-healthy individuals are no longer pooled with healthier people, they can become too costly to insure.

The GAO also found that “contrary to the hopes of CDHP [Consumer-Directed Health Plan] proponents, few of the HSA-eligible plan enrollees who participated in our focus groups researched cost before obtaining health care services.” The GAO noted that accordingly to CDHP proponents, such research activity is central to the cost reductions that proponents assert will be achieved by HSAs and other consumer-driven health care approaches.

We now examine various aspects of the GAO findings in more detail.

The GAO analyzed Internal Revenue Service data on tax filers who reported HSA contributions in 2004. This is the first analysis of IRS data on this matter.[5]

| TABLE 1:

Income of Tax Filers Making HSA Contributions and of All Tax Filers (2004) |

| Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) | Tax Filers Reporting HSA Contributions | All Tax Filers |

| Under $30,000 | 16.2% | 49.8% |

| $30,000-$49,999 | 14.0% | 18.8% |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 18.3% | 13.8% |

| $75,000+ | 51.5% | 17.5% |

| Source: Government Accountability Office. Additional information was provided by GAO staff to CBPP. |

The GAO analysis of the IRS data demonstrates that high-income individuals are benefiting disproportionately from HSAs:

- The GAO found that 51 percent of tax filers reporting HSA contributions in tax year 2004 had an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $75,000 or more. In contrast, only 18 percent of all tax filers under age 65 had incomes this high.[6] (Similarly, although 69 percent of all tax filers under age 65 had incomes below $50,000, only 30 percent of those making a tax-deductible HSA contribution did; see Table 1.

- The average AGI of tax filers reporting HSA contributions in 2004 was $133,000, as compared to $51,000 for all non-elderly tax filers in 2004. (The median AGI of individuals making tax-deductible contributions to their HSAs was $76,000 in 2004, as compared to $30,000 for all tax filers under age 65.)

- The GAO also examined data for three large employers in the public, utility and insurance sectors that offered a choice of health insurance plans, including both a high-deductible plan attached to a HSA and a more traditional, low-deductible Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan.[7] These data are less useful because they cover only three employers, but they are broadly consistent with the IRS data. In two of these employers, the people who enrolled in high-deductible plans attached to HSAs had higher average incomes than the people who enrolled in traditional plans.[8] ; (The third employer reported no differences in income.)

- The IRS data show that high-income individuals not only make disproportionate use of HSAs, but also make much larger tax-deductible contributions to HSA accounts than HSA participants who are less affluent. As a result, high-income households far outpace other Americans in the extent to which they derive substantial tax benefits from HSAs. The IRS data show that HSA participants with adjusted gross income of $200,000 or more made average HSA contributions of $3,010 in 2004. In contrast, HSA participants with incomes below $50,000 made average contributions of $1,370, or less than half as much. The IRS data indicate that tax-deductible HSA contributions rise steadily with income — the higher the income of HSA participants is, the larger the HSA contributions they make (see Figure 1).

- The GAO analysis of IRS data also shows that a large share of the tax filers who make contributions to HSAs appear to be using their HSAs as a tax shelter rather than as a means to pay for ongoing out-of-pocket medical costs. The IRS data indicate that a majority of tax filers who made HSA contributions in 2004 — 55 percent of them — did not withdraw any funds from their HSAs and instead accumulated balances.[9] The GAO noted that such “account holders appeared to use their HSA as a savings vehicle” and that focus group participants reported “using their HSA as a tax-advantaged savings vehicle, accumulating HSA funds for future use.”[10]

The new GAO findings are consistent with other evidence that HSAs are disproportionately attractive to affluent households. In January 2006, the GAO reported that 43 percent of the federal employees in the Federal Employee Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) who are enrolled in a high-deductible insurance plan attached to an HSA had incomes over $75,000. In contrast, only 23 percent of enrollees in other FEHBP plans had incomes this high. The GAO analysis of FEHBP found that the HSA enrollees “had consistently higher incomes across all age groups.”[11] The Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association has presented similar findings with respect to people with incomes over $100,000.[12]

HSAs have a unique tax structure. Not only are contributions to HSAs tax-deductible, but withdrawals from the accounts to pay for out-of-pocket medical costs are tax-free. This tax treatment — under which both contributions to a savings account and withdrawals from that account are tax advantaged — is without precedent in the tax code. (Retirement accounts such as traditional Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and 401(k) plans permit deductible contributions, but withdrawals upon retirement are treated as taxable income. Other plans, such as Roth IRAs, permit tax-free withdrawals but the contributions are not tax-deductible.)

Moreover, because the value of a tax deduction rises with an individual’s tax bracket, HSAs provide the largest tax benefits to high-income individuals. Higher-income people receive a larger tax break for each dollar they put into an HSA than lower-income people do, since they are in a higher tax bracket. For example, an individual in the 35-percent tax bracket saves 35 cents in taxes for each dollar he or she contributes to an HSA, while an individual in the zero, 10-percent, or 15-percent bracket saves no more than 15 cents in taxes for each dollar put into the account. In addition, higher-income people generally can afford to contribute more money into HSAs each year than lower-income people can, which makes HSAs still more valuable to them.

Finally, unlike with traditional IRAs, there are no income limits on participation in HSAs. As a result, affluent healthy individuals who have reached the maximum annual contribution limits on their IRA or 401(k) plans (or who are ineligible to make tax-deductible contributions to IRAs because their incomes exceed the IRA income limits) can use HSAs to shelter a greater share of their income for retirement. HSAs consequently risk being used heavily as a major tax shelter for affluent individuals, causing significant revenue losses to the Treasury and aggravating the nation’s long-term budget problems.

“Adverse selection” occurs when healthy and less-healthy individuals separate into different health insurance arrangements, and the average cost of insurance for the less-healthy group rises significantly because these people are no longer being pooled with healthier individuals who are less expensive to insure. When that occurs, premium costs for the less-healthy group can rise so high that those individuals are put at risk of becoming uninsured or underinsured. ;

Many health policy experts and economists have expressed concern that high-deductible plans attached to HSAs pose a strong risk of fostering adverse selection, because such plans are likely to be disproportionately attractive to healthier individuals who do not need much health care and thus are less concerned about the higher out-of-pocket costs that can result under a high-deductible plan. If healthier individuals move to high-deductible plans attached to HSAs in large numbers over time, while less healthy individuals remain in lower-deductible, comprehensive plans, then significant adverse selection will result and drive up health insurance premiums for the comprehensive plans.[13]

Not surprisingly, when examining national surveys of employers, the GAO found that HSA-eligible plans had higher deductibles and higher limits on in-network, out-of-pocket expenses than more traditional, low-deductible plans did. On the other hand, premiums were lower for the HSA-eligible plans than for the traditional plans (reflecting the less generous insurance coverage the HSA-eligible plans provide).[14] The HSA-eligible plans offered by the three large employers that the GAO studied followed the same pattern: they had higher deductibles and out-of-pocket limits than traditional plans, but lower premiums.[15] ;

The overall result — when deductibles, co-payments, and premiums all were taken into account — was that healthier individuals tended to pay less out-of-pocket under HSA-eligible plans than under traditional plans, while less-healthy individuals tended to pay more. These effects were most pronounced on people with very high health care costs.

For example, the GAO found that in the event of a hospital stay costing $20,000, people enrolled in the HSA-eligible plans offered by the three employers it examined would face total out-of-pocket medical costs 47 to 83 percent higher than the out-of-pocket costs the same people would incur under the traditional plans their employers offered. Total out-of-pocket costs would range from $3,700 to $5,111 under the HSA-eligible plans, as compared to $2,136 to $3,472 under the traditional plans. In contrast, for individuals with low health care needs who required only six physician visits per year, total out-of-pocket costs would be 48 to 58 percent lower under the HSA-eligible plans than under the traditional plans. ;

The GAO also found that one of the three employers provided a sizable contribution to its workers’ HSAs (to help less healthy employees afford higher out-of-pocket costs under a HSA-eligible plan) but another of the three employers provided no contribution and the third employer provided only a modest contribution of $100 for individual coverage and $200 for family coverage. ;The national surveys of employers that the GAO reviewed indicate that about one-third of employers who offer HSA-eligible plans make no contribution to their workers’ HSAs. The amounts contributed by employers who do make contributions are, on average, much lower than the high deductibles.[16]

The GAO concluded that “HSA-eligible plan enrollees would incur higher annual costs than [traditional] plan enrollees for extensive use of health care, but would incur lower annual costs than PPO plan enrollees for low to moderate use of health care.” The GAO expectsthat when individuals decide whether to enroll in HSA-eligible plans or to remain in more traditional, low-deductible plans, “they will likely weigh the savings potential and financial risks associated with these plans in relation to their own health care needs and financial circumstances.” In other words, healthy individuals who need little or no health care are likely to be the people most attracted to high-deductible plans and HSAs, while individuals in poorer health will tend to prefer more traditional, low-deductible plans. ;

The statements of the focus group participants enrolled in HSA-eligible plans buttress this conclusion. The participants generally were satisfied and would recommend HSA-eligible plans to healthy consumers, the GAO reported. But they would not recommend HSA plans “to people who use maintenance medication, have a chronic condition, have children, or may not have the funds to meet the high deductible.” Indeed, some HSA participants said they had enrolled in an HSA-eligible plan because “they did not anticipate getting sick, and many said they considered themselves and their families as being fairly healthy.”[17] ;

While not providing firm evidence, these focus group findings are consistent with other aspects of the GAO report which indicate that high-deductible plans and HSAs are likely to disproportionately attract healthy individuals and thus could provoke “adverse selection” on a significant scale if HSA participation becomes widespread.

HSA proponents believe that widespread adoption of HSAs will have a substantial effect in containing health care costs over time. The theory is that the high deductibles required under HSAs (which are at least $1,050 for individuals and $2,100 for family coverage in 2006) will encourage individuals to be more prudent consumers because they will now be responsible for the cost of health care up to the deductibles and therefore will be more likely to limit use to necessary, cost-effective services.[18]

The GAO found, however, that few focus group participants who were enrolled in HSA-eligible plans researched the cost of care before obtaining health care services. (Many did research the cost of prescription drugs.) In addition, the GAO reported that “limited information was available regarding key quality measures for hospitals and physicians, such as the volume of procedures performed and the outcomes of these procedures.” ;Focus group participants said that in selecting health care providers, they relied on traditional approaches such as referrals from family and friends and the recommendations of other providers. These results cast doubt on the current ability of patients with HSA-eligible plans to “shop around” and obtain lower-cost, high quality care that helps to restrain overall health care spending.

Health and tax policy analysts long have warned that HSAs could be used extensively as tax shelters by high-income individuals. They have also expressed concerns that HSAs would be disproportionately attractive to healthier individuals and risk adverse selection. The GAO’s analysis of the IRS data, as well as its case studies of three large employers, lend strong credence to these concerns.

In its concluding observations, the GAO warns that “when individuals are given a choice between HSA-eligible and traditional plans — as in the individual market and with employers offering multiple health plans — HSA-eligible plans may attract healthier individuals who use less health care or, as we found, higher-income individuals with the means to pay higher deductibles and the desire to accrue tax-free savings.” ;

The GAO has thus effectively added its voice to the voices of health policy experts who have warned that HSAs may result in adverse selection, with healthier and less-healthy people separating into different insurance arrangements. If adverse selection becomes widespread, it is likely to pose serious risks to those Americans who are in poorer-than-average health, since the higher health care costs they must incur will no longer be pooled with the lower costs of individuals who are healthy. An increase in the number of Americans with below-average health who are uninsured or underinsured — or who receive adequate health insurance only by failing to meet other basic needs — would not be a desirable outcome for the nation.