Some Republican leaders have proposed block-granting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) or capping its funding and merging it with other programs.[1] Converting SNAP to a block grant would rob it of its most important structural feature: the guarantee it provides across the country to help low-income households afford an adequate diet. Any changes to SNAP that would end this guarantee of food assistance to the individuals and families that meet its strict eligibility standards would risk serious harm to millions of low-income families, senior citizens, and people with disabilities who use SNAP’s benefits to put food on the table each month.

SNAP is one of the few federal guarantees for the poor. Despite its modest benefits — only about $1.40 per person per meal, on average — SNAP is a critical foundation for low-income households’ health and well-being. Key problems with a SNAP block grant include:

-

SNAP would no longer respond to changes in need. SNAP is the most responsive means-tested program to changes in poverty and unemployment during economic downturns. It expands to meet need and then shrinks when need recedes, most recently during and after the Great Recession of 2007-09. This automatic response not only eases hardship for people directly hit by a downturn but also boosts economic activity in communities across the country, thereby acting as an “automatic stabilizer” for the weak economy.

In contrast, a block grant that gave states a fixed amount of money each year would not respond when more households needed food assistance due to a downturn or natural disaster. States would have to bear the entire cost of added food assistance themselves or make cuts to stay within the block grant amount.

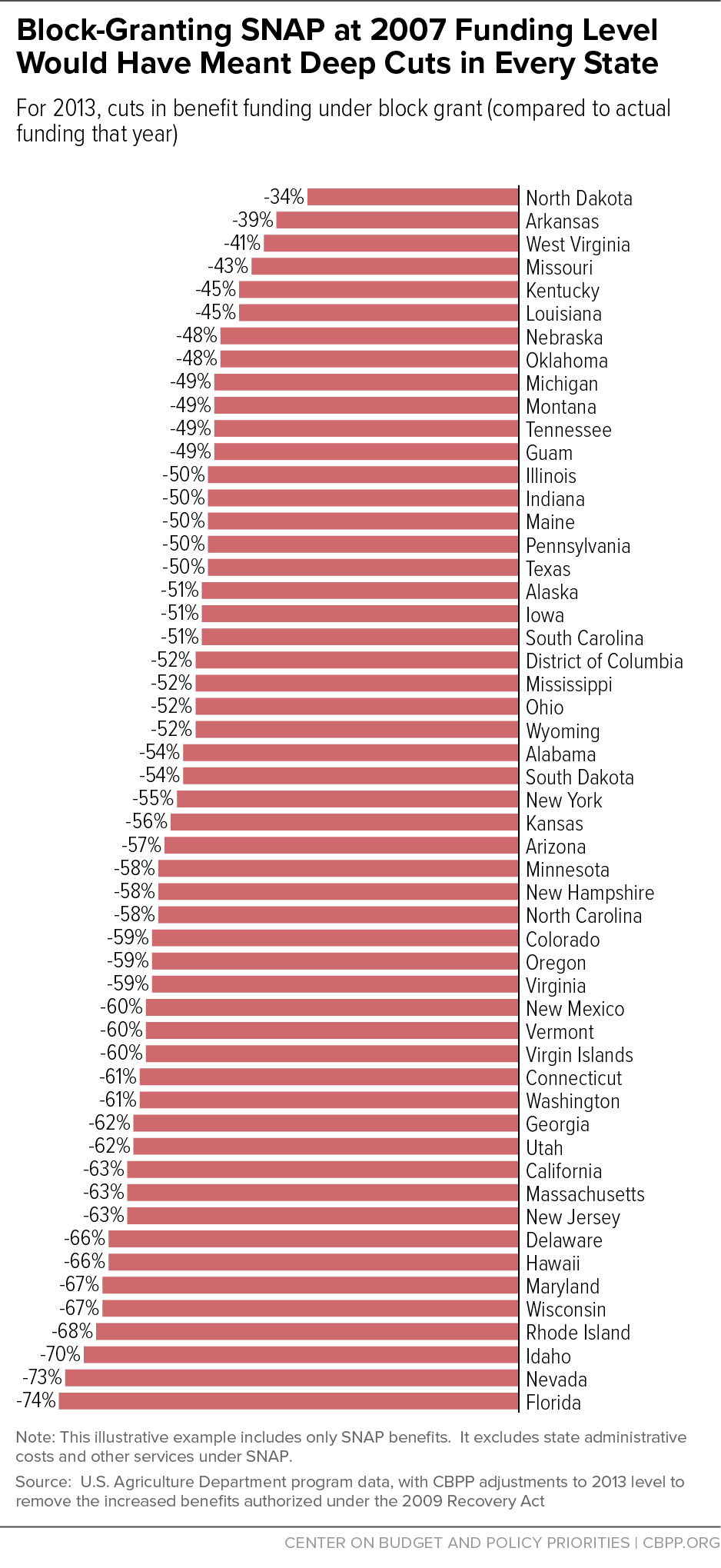

Had a block grant been in effect in 2013 at funding levels set in 2007, before the recession, federal SNAP funding in 2013 would have been about half its actual level that year. Some states would have received less than half of the funding they actually received. (See the Appendix for state-by-state figures.)[2]

Also under a block grant, people experiencing a crisis like a job loss, divorce, or health emergency could no longer count on getting help with groceries for their families regardless of where they live.

-

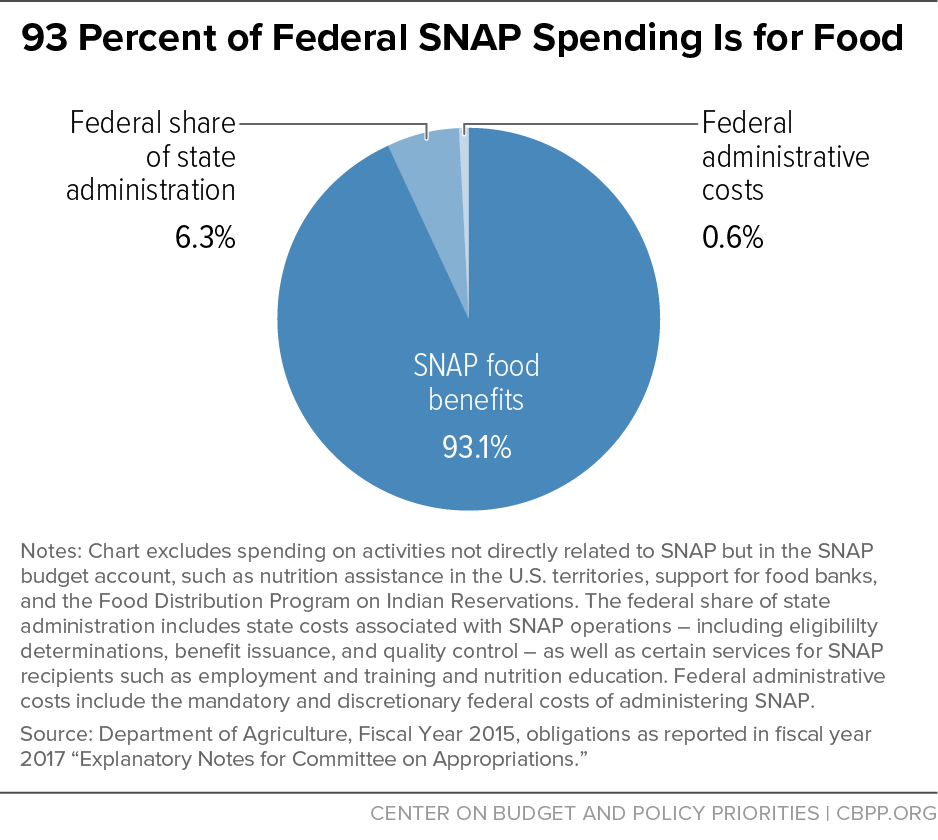

States would likely make deep cuts in eligibility or benefits. A SNAP block grant accompanied by large cuts, as in recent House Republican budgets, would necessitate deep cuts in eligibility or benefits. More than 90 percent of SNAP goes to benefits for purchasing food, so states would have few other places to achieve the required cuts.

For example, the most recent House Republican budget resolution assumed a SNAP block grant beginning in 2021 with $125 billion in cuts over the 2021-2026 period. If the states offset these cuts solely by tightening SNAP eligibility, they would have to cut an average of 10 million people from the program (relative to enrollment under current law) each year between 2021 and 2026. If the cuts came solely from across-the-board benefit cuts, states would have to cut an average of more than $40 per person per month.

It is worth noting that SNAP is not projected to increase even without cuts. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the number of SNAP participants to continue falling over the next decade by about 2 to 4 percent a year and projects that SNAP benefits, which are adjusted for food prices, will rise modestly, by about 2 percent a year without adjusting for inflation.[3]

- States would likely shift food assistance funds to other uses. Block-granting SNAP would significantly reduce accountability over states’ use of federal dollars. States could shift SNAP funds to other purposes — just as they have with funds under the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant — and they would likely do so when faced with budget shortfalls. As a result, the cuts to food assistance to low-income households under a block grant likely would be even deeper than the cut in federal SNAP funding.

- Program integrity would likely be compromised. SNAP includes one of the most rigorous payment accuracy systems of any public benefit program. States have achieved the highest payment accuracy rates in the program’s history in recent years, with less than 4 percent of SNAP benefits issued to ineligible households or to eligible households in improper amounts, according to the most recent U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data. The federal government also devotes substantial resources to combatting SNAP fraud. If SNAP were a block grant, much of this activity to reduce errors and combat fraud could shift to states, but few states could match the capacity and resources of the federal government to retain this rigorous oversight of federal dollars.

SNAP works; there is no evidence that a block grant would produce better results. SNAP lifts millions of households out of poverty and helps tens of millions come closer to affording an adequate diet. Research finds that it improves children’s health and helps them do better in school. Moreover, access to SNAP when children are very young has been found to improve their long-term health and economic outcomes. Supporters of a SNAP block grant contend that giving states new flexibility would allow them to innovate, but without cutting food assistance even deeper, states would have no resources to improve the program by, for example, enhancing benefits or services, investing in employment and training, or improving participation among seniors or working families, two groups with historically low participation rates. As a result, poverty and hardship would go up, not down under a block grant.

Under current SNAP rules, the federal government commits to make food assistance through SNAP available to every household that qualifies under program rules and applies for help. This is one of the few federal guarantees on meeting low-income households’ most basic needs. A block grant would end that commitment, instead providing states with a fixed amount of funding. Some argue that a block grant could be adjusted in response to changes in states’ eligible population, food prices, or other factors, but such ad hoc adjustments could not be anticipated or enacted quickly enough. The best mechanism is the structural guarantee that SNAP already has in place.

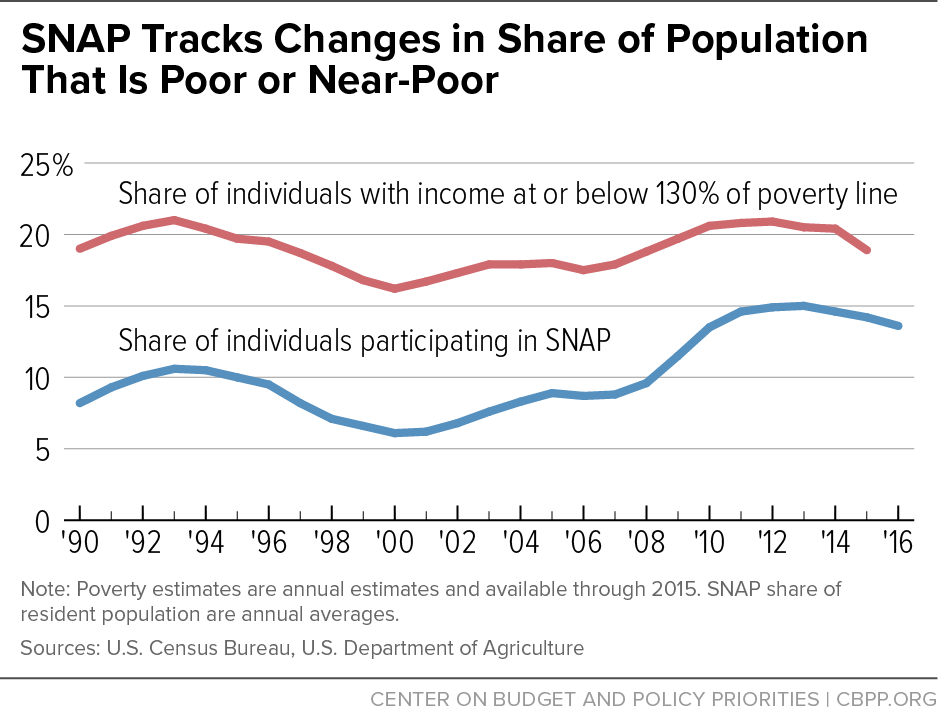

SNAP is the most responsive means-tested program to changes in poverty and unemployment during economic downturns. It expands to meet need and then shrinks when need recedes. The recent Great Recession followed this pattern, as SNAP responded quickly to increases in poverty after the recession hit. SNAP enrollment tracked poverty levels, reaching all-time highs in late 2012, and has since begun receding (see Figure 1).[4]

SNAP’s automatic response to economic downturns not only eases hardship for people directly hit by the downturn but also boosts economic activity in communities across the country, thereby acting as an “automatic stabilizer” for the weak economy. SNAP benefits are available quickly (within a month of application, and typically even faster) and recipients spend them quickly. Economists at CBO and Moody’s Analytics consider SNAP one of the most effective forms of stimulus in a weak economy.[5]

Block granting SNAP would eliminate its ability to respond immediately to fluctuations in the economy. States would receive a fixed amount of funding at the beginning of the year; if unemployment rose and more people qualified and applied for food assistance, federal funding would not respond. As a result, states would have to bear the entire cost of added food assistance themselves (even as state revenues were declining), cut food benefits, eliminate eligibility altogether for some households, or place new applicants on waiting lists despite the downturn. By contrast, under SNAP’s current structure, the federal government bears 100 percent of the added food assistance costs resulting from a weak economy.

Had a block grant been in effect in 2013 at funding levels set in 2007, before the recession, federal SNAP funding in 2013 would have been about half the level available under regular SNAP rules that year.[6] Arizona, for example, would have received $650 million in SNAP benefits in 2013, less than half the roughly $1.5 billion it received. In states hit even harder by the recession, such as Florida and Nevada, the difference would have been greater. (See Figure 2 and the Appendix for state-by-state figures.) Even in less severe recessions, a block grant’s inability to respond to increased need would result in significantly less food assistance.

States can provide emergency SNAP within a matter of days or weeks to help disaster victims buy food. States use this authority after widespread disasters, such as major hurricanes or floods, as well as localized tornadoes or severe winter storms that cause power outages in specific communities.

SNAP often is one of the first government relief efforts in place after a disaster. If SNAP were instead a block grant and the authority for disaster benefits were eliminated, it could take several months for federal disaster benefits to become available. SNAP disaster benefits reached residents within one month of October 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, for example, while Congress did not enact additional disaster relief for the hurricane’s victims until January 2013.

Individuals often qualify for SNAP due to a personal crisis, such as a job loss, divorce, or health emergency. SNAP’s current structure enables it to provide almost immediate help in bridging temporary periods of unemployment or crisis. Under a block grant, when funds ran short, states would likely have to restrict eligibility and could resort to waiting lists — as occurs with child care and housing assistance, where need in most communities far outpaces available funding. As a result, food assistance would be less likely to be available to people with a shorter-term need for help, including many working families.

Moreover, a block grant could create a disincentive to work. Currently, SNAP households that leave the program because they found a job or got a raise can count on SNAP being available if they need help again later. Under a block grant, such households might have to wait until funding became available to resume benefits. Thus, a block grant could increase the perceived risks of working, making it harder for low-income families to take a chance on a new job or promotion.

Block-granting could affect work incentives in another way. Currently, SNAP benefits decline by only 24 to 36 cents for each additional dollar in household earnings, so SNAP participants know their total income will rise if their earnings rise. (Put another way, SNAP does not have a significant “benefit cliff,” where people are worse off working than if they receive safety-net benefits.) Under a block grant, states looking to cut food assistance costs might phase out benefits more quickly as earnings rise or cut off SNAP eligibility at a lower income level, which could introduce benefit cliffs and discourage work.[7]

Proposals to block-grant SNAP and turn SNAP policy over to states often aim to cut federal SNAP funding significantly over time without specifying exactly who would lose benefits, or how much. Each of the last six House Republican budget resolutions proposed to convert SNAP to a block grant SNAP or “State Flexibility Fund,” accompanied by cuts of $125 billion or more over ten years, or about 20 to 30 percent.[8]

Cuts of the magnitude contemplated by the House Republicans would force states to substantially scale back eligibility or benefits, with significant effects on low-income people.[9] Consider these illustrative examples of the possible impact of the cuts in the most recent House Republican budget resolution, based on a SNAP block grant beginning in 2021 with $125 billion in cuts over the 2021-2026 period. The cut in a typical year would exceed the total SNAP benefits projected to go under current law to the 36 smallest states and territories over this period.[10]

-

Eligibility cuts. If the cuts came solely from eliminating eligibility for certain categories of households or individuals, states would have to cut an average of 10 million people from the program (relative to enrollment under current law) each year between 2021 and 2026.[11]

States also could tighten SNAP eligibility by lowering the program’s income limit. To achieve a 29 percent cut in overall benefits paid (as the House budget would, beginning in 2021), the SNAP income limit would have to be set at about 68 percent of the poverty level, or about $1,140 a month in 2017 for a family of three. The current federal limit is 130 percent of the poverty level ($2,200 a month). This approach would eliminate eligibility for many working families, senior citizens, and people with disabilities.[12]

-

Benefit cuts. If the cuts came solely from across-the-board benefit cuts, states would have to cut an average of more than $40 per person per month in 2021 to 2026 (in nominal dollars). This would require setting the maximum benefit at about 77 percent of the cost of the Thrifty Food Plan, USDA’s estimate of the cost of a bare-bones, nutritionally adequate diet. (SNAP’s maximum benefit, which goes to households with no disposable income after deductions for certain necessities, is set at 100 percent of the Thrifty Food Plan.)[13]

Such a change would have a pronounced impact. All families of four — including the poorest — would face benefit cuts of about $165 a month in fiscal year 2021, or almost $2,000 per year. All families of three would face cuts of about $130 per month, or almost $1,550 per year. Policymakers could shield some households from cuts, but then other households would need to bear even larger cuts to produce the $125 billion in block-grant savings.

While states might not seek to hit the targets through just one of these approaches, these examples illustrate the magnitude of the reductions needed. States would have few other places to achieve the required cuts. In 2015, 93 percent of federal SNAP spending went for benefits to purchase food.[14] The rest went for administrative costs, including reviews to determine that applicants are eligible, monitoring of retailers that accept SNAP, and anti-fraud activities. (See Figure 3.)

House Republicans’ budget documents claim their proposed block grants would “give power back to the states so they have the flexibility to implement these programs and meet the diverse needs of their populations, improving health and economic outcomes.”[15] But under a block grant, states’ added flexibility would primarily be to decide how to cut food assistance. States would have no new resources available. They would need to cut food assistance deeper or invest their own resources (with no federal contribution) in order to enhance benefits or services, invest in employment and training programs, or improve participation among seniors or working families (two groups with historically low participation rates). As a result, poverty and hardship would go up, not down under a block grant. There is no evidence states would be able to improve outcomes for low-income families and individuals.

Under SNAP’s current structure, each state’s federal SNAP funding is based on the number of eligible households that apply, so the amount each state needs to serve all eligible applicants is automatically available. If funding were instead allocated by a formula, it is highly likely that some states where SNAP caseloads are shrinking due to factors such as a decline in poverty or in SNAP participation rates would face smaller cuts than other states (relative to current law), since their block-grant allocation probably would not be reduced to reflect these declines. Conversely, states where the poverty population is growing or where participation rates have historically been low would face even deeper cuts than other states. (House Republicans have not specified the formula they would use to allocate a national block grant to the states.)

Moreover, history suggests that there is a substantial risk that a SNAP block grant’s value would weaken over time. Since 2000, overall funding for the 13 major housing, health, and social services block grant programs has fallen by 27 percent after adjusting for inflation, and by 37 percent after adjusting for inflation and population growth.[16]

States’ added flexibility under a SNAP block grant would enable them to transfer significant amounts of food assistance spending to fund other priorities. As a result, the cuts in food assistance to low-income households likely would be even deeper than the cut in federal SNAP funding.

The TANF block grant serves as a cautionary tale.[17] When policymakers block-granted programs for cash assistance, employment, child care, and other services for very low-income families as TANF in 1996, proponents argued that states would use their flexibility to improve work programs and work supports. But that is not what happened. Over time, states redirected a large part of their state and federal TANF funds to other purposes: to fill state budget holes, and in some cases to substitute for existing state spending. The bulk of funds withdrawn from the cash assistance safety net have not gone to help connect families to work or support low-income working families. In fact, states use only about half of their TANF funds for the program’s basic purposes of cash assistance for poor families, work or employment preparation programs, or child care so parents can work. And when need rose during the Great Recession, states for the most part did not bring the funds back to these core purposes of TANF; some states cut them more.

Even if a SNAP block grant is more limited than TANF in how the funding can be spent, states would likely face similar pressures to shift funds under a SNAP block grant and would have ample opportunity to do so. For example:

- States could replace state administrative funds with federal benefit funds. Currently, each state pays about half of SNAP’s administrative costs (e.g., eligibility staff, computers, office space, and issuing benefits); states spend roughly $4 billion a year in this area. Under a block grant, states likely would face pressure to replace that state spending with federal block grant funds, freeing up state funds for uses unrelated to food assistance for low-income families. Using federal funds to cover administrative costs, however, would force states to cut food assistance benefits to households even more.

- States could transfer food assistance to employment and training, child care, and related services and withdraw state funds. SNAP includes components for employment and training and related child care and transportation services. A state facing budgetary pressures could divert federal SNAP benefit funds to these employment and training purposes, then scale back state funding for these programs and use the freed-up state funds however it chose.

These funding shifts would help states facing budget problems to plug budget holes or to find resources for new spending or tax-cut initiatives unrelated to food assistance for low-income families.

SNAP includes one of the most rigorous payment accuracy systems of any public benefit program and one of the best records of accuracy in providing benefits only to eligible households. In recent years SNAP payment accuracy has reached all-time highs, with less than 4 percent of SNAP benefits issued to ineligible households or to eligible households in improper amounts, according to the most recent USDA data.[18]

Households applying for SNAP report their income and other relevant information; a state eligibility worker interviews a household member and verifies the accuracy of the information using data matches, paper documentation from the household, or by contacting a knowledgeable party, such as an employer or landlord. Subsequently, each month, states pull a representative sample (annually totaling about 50,000 cases nationally) and thoroughly review the accuracy of the eligibility and benefit decisions. Federal officials re-review a subsample of the cases to ensure accuracy in the error rate they assign each state. States face financial penalties if their error rates are persistently above the national average.

The federal government also devotes substantial resources to combatting SNAP fraud. USDA authorizes the more than 250,000 retail food stores that participate in SNAP and monitors fraud through a sophisticated national system that identifies suspicious benefit redemption patterns. Federal undercover agents visit suspicious stores and gather evidence of illegal activity.

If SNAP were a block grant, much of this activity to reduce errors and combat fraud could shift to states, but few states could match the capacity and resources of the federal government to retain this rigorous oversight of federal dollars.

Numerous other efficiencies stem from federal oversight and would disappear under a block grant. For example, because SNAP now has a consistent set of rules for eligibility and income verification backed up by federal oversight, other programs can streamline their eligibility processes — and achieve administrative savings as a result — by relying on determinations done by SNAP. Both the school meal programs and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) use SNAP determinations to assess program eligibility automatically. A block grant would call the rigor of SNAP’s eligibility determinations into question, potentially raising costs for other programs.

Since the early 1970s, SNAP has served as national nutritional guarantee and has achieved significant, measurable success.[19] While improvements could be made to SNAP to strengthen its benefits, expand its reach to better serve all low-income people in need, enhance its employment and training services, and strengthen program integrity, changing it to a block grant with deep cuts would impede, not promote, progress in these areas.

- SNAP has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States. A team of Field Foundation-sponsored doctors who examined hunger and malnutrition among poor children in the South, Appalachia, and other very poor areas in 1967 (before the Food Stamp Program, as SNAP was then named, was widespread in these areas) and again in the late 1970s — after the program had been instituted nationwide — found marked reductions over this period in serious nutrition-related problems among children. They gave primary credit to food stamps.[20] Findings such as this led Senator Robert Dole to describe the Food Stamp Program as the most important advance in U.S. social programs since Social Security.

-

SNAP is targeted at need and reduces poverty. SNAP reaches more than 80 percent of eligible households, USDA estimates.[21] It delivers the largest benefits to those least able to afford an adequate diet; roughly 92 percent of benefits go to households with monthly incomes below the poverty line, and 57 percent go to households below half of the poverty line, or below $840 a month for a family of three in 2017.

These features help account for SNAP’s large anti-poverty impact. SNAP kept 8.4 million people out of poverty in 2014, including 3.8 million children, and made millions more less poor, according to Census data using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (which counts SNAP and other non-cash benefits as income). SNAP also lifted 2.1 million children above half of the poverty line.[22]

-

SNAP helps low-income households put food on the table and improves long-term health and well-being. SNAP benefits reduce food insecurity (which occurs when households lack consistent access to nutritious food because of limited resources) among high-risk children by 20 percent and improves their overall health by 35 percent, one study found.[23] Another recent study found that participating in SNAP reduced households’ food insecurity by about five to ten percentage points and reduced “very low food security,” which occurs when one or more household members have to skip meals or otherwise eat less because they lack money, by about five to six percentage points.[24]

Moreover, recent research comparing the long-term outcomes of individuals in different areas of the country when SNAP gradually expanded nationwide in the 1960s and early 1970s found that disadvantaged children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health and educational outcomes as adults than children who didn’t have access to food stamps. Among other things, children with access to food stamps were less likely in adulthood to have stunted growth, be diagnosed with heart disease, or be obese. They also were more likely to graduate from high school.[25]

-

SNAP’s national benefit structure is key to these successes. States have a high degree of flexibility in how the operate the program, but SNAP’s benefit levels and eligibility rules largely are uniform across the states. The national benefit structure was established under President Nixon after an initial effort to operate the program without such standards resulted in enormous disparities across states, with some states setting income limits as low as half the poverty line.

The national benefit structure ensures that poor families can obtain adequate nutrition, regardless of where they live. It also substantially reduces differences across the states in their overall financial support for poor children — a fact of special importance to southern states and rural areas, which have lower cash assistance benefits, higher poverty, and lower fiscal capacity. A block grant would eliminate SNAP’s national guarantee. Not only would it halt progress at improving SNAP’s reach in areas with low participation historically, but the deep cuts in federal funding would very likely increase hunger and hardship in many parts of the country.

There is no evidence that state flexibility under a block grant could improve upon these documented results.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Total SNAP Benefits, 2007 |

Total SNAP Benefits, 2013 |

Difference |

Percentage Difference |

|---|

| Alabama |

601 |

1,305 |

-703 |

-54% |

| Alaska |

86 |

175 |

-89 |

-51% |

| Arizona |

647 |

1,520 |

-873 |

-57% |

| Arkansas |

412 |

675 |

-262 |

-39% |

| California |

2,570 |

6,969 |

-4,399 |

-63% |

| Colorado |

311 |

759 |

-449 |

-59% |

| Connecticut |

253 |

652 |

-399 |

-61% |

| Delaware |

75 |

217 |

-142 |

-66% |

| District of Columbia |

104 |

217 |

-113 |

-52% |

| Florida |

1,400 |

5,446 |

-4,045 |

-74% |

| Georgia |

1,126 |

2,940 |

-1,814 |

-62% |

| Hawaii |

157 |

456 |

-299 |

-66% |

| Idaho |

96 |

320 |

-224 |

-70% |

| Illinois |

1,565 |

3,115 |

-1,549 |

-50% |

| Indiana |

677 |

1,347 |

-670 |

-50% |

| Iowa |

265 |

541 |

-275 |

-51% |

| Kansas |

193 |

437 |

-244 |

-56% |

| Kentucky |

674 |

1,229 |

-555 |

-45% |

| Louisiana |

746 |

1,364 |

-618 |

-45% |

| Maine |

171 |

338 |

-168 |

-50% |

| Maryland |

357 |

1,087 |

-729 |

-67% |

| Massachusetts |

472 |

1,286 |

-814 |

-63% |

| Michigan |

1,368 |

2,685 |

-1,317 |

-49% |

| Minnesota |

296 |

711 |

-415 |

-58% |

| Mississippi |

444 |

916 |

-472 |

-52% |

| Missouri |

745 |

1,317 |

-572 |

-43% |

| Montana |

90 |

177 |

-88 |

-49% |

| Nebraska |

126 |

244 |

-118 |

-48% |

| Nevada |

134 |

493 |

-360 |

-73% |

| New Hampshire |

62 |

150 |

-88 |

-58% |

| New Jersey |

483 |

1,309 |

-825 |

-63% |

| New Mexico |

249 |

626 |

-378 |

-60% |

| New York |

2,324 |

5,183 |

-2,859 |

-55% |

| North Carolina |

972 |

2,297 |

-1,325 |

-58% |

| North Dakota |

52 |

79 |

-27 |

-34% |

| Ohio |

1,293 |

2,695 |

-1,402 |

-52% |

| Oklahoma |

459 |

884 |

-425 |

-48% |

| Oregon |

477 |

1,153 |

-675 |

-59% |

| Pennsylvania |

1,259 |

2,534 |

-1,275 |

-50% |

| Rhode Island |

89 |

279 |

-190 |

-68% |

| South Carolina |

618 |

1,274 |

-656 |

-51% |

| South Dakota |

71 |

152 |

-82 |

-54% |

| Tennessee |

1,004 |

1,962 |

-958 |

-49% |

| Texas |

2,718 |

5,472 |

-2,753 |

-50% |

| Utah |

133 |

348 |

-215 |

-62% |

| Vermont |

56 |

138 |

-83 |

-60% |

| Virginia |

551 |

1,330 |

-778 |

-59% |

| Washington |

601 |

1,548 |

-947 |

-61% |

| West Virginia |

275 |

465 |

-190 |

-41% |

| Wisconsin |

363 |

1,105 |

-741 |

-67% |

| Wyoming |

25 |

53 |

-27 |

-52% |

| Guam |

56 |

109 |

-53 |

-49% |

| Virgin Islands |

21 |

53 |

-32 |

-60% |

| United States |

30,373 |

70,134 |

-39,760 |

-57% |