Funding for Florida schools, universities, roads and bridges, health programs for children and the elderly, public transit, and a wide range of other public services will fall significantly if voters enact Amendment 3 on Florida’s November statewide ballot. This constitutional amendment would severely limit the amount of state revenue that the state can spend on services, using a formula that led to drastic cuts in public services in Colorado — the only state to have tried it.

Amendment 3 was designed to defer the cuts for several years, obscuring the severe long-term damage it would do to the state. Once the cuts started, however, they quickly would grow very large and would then continue to expand, as happened in Colorado before voters suspended the harsh formula (known as TABOR or “Taxpayer Bill of Rights”).

- Once fully in place, Amendment 3 would cause severe damage. As an illustration, we calculate that if the measure were to take full effect today, state revenue losses would exceed $11 billion over just ten years.

- Amendment 3 would result in deep reductions in funds for Florida’s schools and universities. Nearly half of the revenues subject to the Amendment 3 cap support public schools and universities. Thus, Amendment 3 would increasingly limit the revenues available to maintain the state’s education system, let alone improve it and respond to emerging needs. The ballot description of Amendment 3 includes highly deceptive language suggesting the measure would increase K-12 funding when just the opposite is true: Amendment 3 would significantly shrink state revenue used to fund schools (and other public services).

-

Health services for children and the elderly also would face cuts. Amendment 3 would limit funding for the medical care of over 250,000 children and place at risk certain health services for the elderly, including Alzheimer’s care. Some Medicaid coverage would be at risk as well, since Amendment 3’s cap applies to part of Florida’s Medicaid spending. In addition, funds that the state sets aside to reimburse hospitals for uncompensated medical care of the indigent would fall under the cap, likely leaving hospitals to either foot more of the bill for that care or pass on the additional costs to other patients.

- Amendment 3 would make it much more difficult to build and maintain schools, roads, clean water systems, and other infrastructure projects. Amendment 3’s revenue cap could immediately raise the cost of borrowing for infrastructure projects, from new schools and roads to systems that sustain Florida’s many natural resources and preserves, by leading credit-rating agencies to downgrade the state’s bond rating. At the same time, the measure would limit state funding for maintenance both of Florida’s roads, bridges, ports, and other transportation systems and of the integrity of the state’s air and water quality and natural resources, leading to their deterioration over time.

Amendment 3 has the same fundamental flaw of Colorado’s TABOR: it would limit revenue growth to the combined rate of population growth and inflation. This arbitrary formula fails to match up to the normal growth in the cost of public services for at least two reasons. First, it is based on overall state population growth, rather than growth among groups to whom many public services are targeted, such as children and seniors. Second, its measure of inflation is changes in the price of the goods that consumers buy rather than changes in the cost of the services state governments provide, like building schools and roads (for more discussion, see the Appendix).

Colorado’s experience with TABOR highlights the damage that Amendment 3 could cause to public services in Florida. Under TABOR, Colorado fell from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12 spending as a share of personal income, for example, and from 24th to 50th in the share of children receiving their full vaccinations. Florida already lags behind most other states on various education and health measures and could fall further under Amendment 3’s revenue restrictions.

Amendment 3 would have other negative impacts, as well. It would reduce legislative accountability, since most of the legislators who voted to put it on the ballot would no longer be in office (because of term limits) when the time came to make the difficult cuts it would eventually require. And, by imposing a supermajority vote of each house to override the limit, it would increase the risk of legislative gridlock and enable a minority of legislators to block the override unless their pet projects get funded.

In short, adoption of this measure would make Florida a much less attractive place to work and live by undermining the state’s ability to fulfill its current responsibilities toward its residents and make long-term investments that are fundamental to future prosperity.

The Florida legislature voted in 2011 to place Amendment 3 on the November 2012 ballot. The following are the key provisions of Amendment 3:

- The proposal bars the state government from collecting and spending state revenues in excess of a prescribed limit. The limit for each year equals the previous year’s limit, adjusted by the average for the preceding five years of the combined rates of annual inflation (defined as the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, U.S. city average) and population growth.

- The base year for the formula — that is, the year that would determine future years’ limits — is fiscal year 2013-14. In each of the first four years of implementation, the limit includes not only the inflation and population-growth adjustments described above but an additional upwards adjustment. This adjustment allows an additional four percentage points of growth to the limit in the first year (i.e. 2014-15), three points in the second year, two points in the third year, and one point in the fourth year (2017-18). There would be no additional adjustment after the fourth year.

- The revenue limit applies broadly to state taxes, fees, assessments, licenses, fines, and charges for services. There is a major exemption: state spending on the parts of Medicaid that are deemed “mandatory” under federal law, as well as the parts that were expanded at state option before 1994, are exempt from the limit. Other exemptions include lottery revenues that are returned as prizes and receipts of the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund and the Citizens Property Insurance Corporation. Interest payments on bonds issued July 1, 2012, or later would not be exempt. Newly created revenue sources would be subject to the limit as well, unless placed in the state’s constitution by amendment.

- Revenues in excess of the formula limit would go into the Budget Stabilization Fund, which is intended to help the state weather a recession or emergency, until the fund reaches its limit under state law (10 percent of the prior fiscal year’s net revenue collections for the general fund). Any additional excess revenues would be used to reduce property taxes for the required local contribution to K-12 education.

- It would take a legislative supermajority to override the revenue limit. The legislature could override the limit for one year at a time with a three-fifths vote of each house, but after that, the limit reverts to where it otherwise would have been. A multi-year or permanent override would be even more difficult, requiring either a two-thirds vote in each house or a three-fifths vote of the legislature plus approval by at least 60 percent of voters.

Amendment 3 would cap the revenues that finance almost everything the state of Florida does: education (both pre-K through 12 and higher education), health care, transportation, natural resource protection and development, economic development and tourism promotion, public safety, administration of the court system, funds for local governments, and so on. (The only major exclusion is for most of Medicaid spending; see the box on p. 3 for a full description of the measure.) Such services are essential for Florida’s long-term prosperity. Numerous surveys of business executives, for instance, find that a well-educated workforce, sound infrastructure, and a good quality of life are the attributes that attract them to a state to invest and create jobs.

Adoption of Amendment 3 would make it increasingly difficult for the state to provide these services. Once it took full effect, the measure would hold state revenues to a rate of growth — the combined rate of overall inflation and population growth — that cannot keep pace with the normal costs of maintaining existing public services. (See the Appendix for a detailed explanation of why the formula is flawed.)

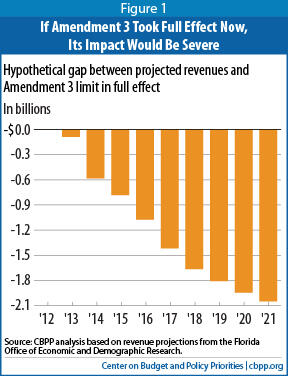

To illustrate, Figure 1 models the hypothetical impact of Amendment 3 on state revenues if it took full effect for the current fiscal year (2012-13) with no phase-in period.

- State revenues for funding services would shrink by about $89 million in fiscal year 2012-13, by $580 million in fiscal year 2013-14, by $780 million in fiscal year 2014-15, and by over $1 billion in fiscal year 2015-16.

- By the 2020-21 fiscal year, the difference between projected revenues and revenues allowed under Amendment 3 would exceed $2 billion each year. That’s roughly equal to half of the state’s entire projected Transportation Trust Fund in 2021 to maintain and improve roads, highways, ports, and public transit.[1]

- The cumulative revenue loss under Amendment 3 would reach $11.4 billion in the first ten years.

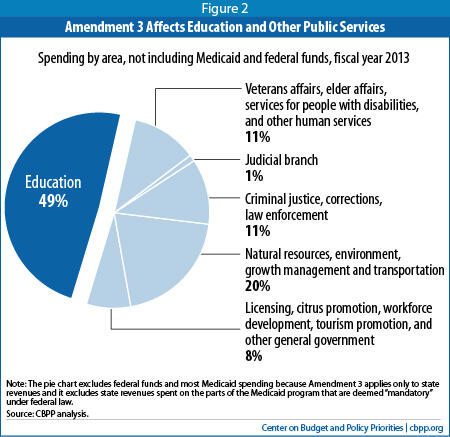

It would be nearly impossible for the state to deal with Amendment 3’s large revenue losses without cutting education funding. Some 49 percent of the state funds restricted under Amendment 3 go to schools and universities.

Florida might try to limit the impact on its education system by cutting other state services first. But it is hard to imagine that a funding area that represents half of revenues under the cap — even one with broad popular appeal and an indisputable importance to the state’s economic future, like education — could escape major cutbacks.

Colorado’s experience is instructive. TABOR forced lawmakers to make deep cuts to nearly every major area of spending, including schools, universities, and health care — all areas that, in Colorado at least as much as in Florida, are recognized as essential to the state’s economy and quality of life. (See pp. 9-11 for a more detailed discussion of the Colorado experience.)

Florida schools rely heavily on state funding to pay for teachers, books, and other necessities. Statewide, 52.4 percent of school district operating funds for pre-kindergarten through grade 12 come from the state.[2] State funds are particularly important for assuring that schools in rural and low-income areas with few options for raising other funds can provide an adequate education. They also help school districts across the state reduce class sizes.

The past four years help illustrate the likely fate of schools and universities under Amendment 3. When the 2007-09 recession hit, revenues plummeted and Florida’s lawmakers chose to make deep cuts to public schools and universities to help balance the budget. As a result, by fiscal year 2011-12 K-12 spending per student had fallen to 18 percent below 2007-08 levels, after adjusting for inflation; despite some improvement it remains well below pre-recession levels.

[3] Likewise, cuts to higher education funding have led Florida’s 11 public universities to raise tuition by more than 50 percent since the 2009-10 school year.

[4] A provision in Amendment 3 may lead some voters to think that the Amendment would improve school funding, but this is not the case. As the box on page 6 explains, Amendment 3 would instead cut state funding for schools.

Language that the legislature submitted to describe Amendment 3 on Florida’s November ballot could lead voters to believe, incorrectly, that Amendment 3 provides extra support for Florida’s schools. The language says:

Under the amendment, state revenues … collected in excess of the revenue limitation must be deposited into the budget stabilization fund until the fund reaches its maximum balance, and thereafter shall be used for the support and maintenance of public schools by reducing the minimum financial effort required from school districts for participation in a state-funded education finance program.

This reference to support and maintenance of public schools is highly misleading. Schools would receive zero extra dollars for education under Amendment 3; to the contrary, school funding would almost certainly be cut. Here’s how it would work in a year when the Amendment 3 limit is capping state revenues and the budget stabilization fund is already full:

- Revenues in excess of the limit would go to reduce the amount of revenue that school districts are required to raise in property taxes. In other words, state funds would replace local property tax funds; they would not increase overall money for the school district.

- Meanwhile, overall funding for school districts would most likely be cut because Amendment 3 would cap the total funds available for services like education.

- At best, the net effect on school funding would be no new funding. More likely, funding would shrink.

Because of Amendment 3’s effect on state funding for education, groups like the Florida PTA, the Florida Education Association, the United Faculty of Florida, and the Florida Association of School Administrators all oppose the measure.

Health services for the elderly and children also would face cuts under Amendment 3. The measure’s population-plus-inflation formula is calculated from a general rate of inflation that is consistently well below the rate of health care inflation. The state could limit health expenditures to a general inflation rate only by reducing the services available or the number of people who can receive care; otherwise, health services would use up an ever-growing share of Florida’s increasingly restricted revenues, requiring even deeper cuts in other services than would already occur.

Major health impacts would occur even though Amendment 3’s revenue limit would not apply to the bulk of state dollars that help fund Medicaid. The measure exempts the coverage of Medicaid services and populations that the federal government lists as “mandatory,” as well as the coverage of non-mandatory services and populations initiated prior to July 1, 1994. Despite this large carve-out, the Amendment 3 cap would apply to non-mandatory Medicaid expansions made on or after July 1, 1994, as well as to other health services not covered by Medicaid.

For example:

- Some so-called “optional” Medicaid coverage would face cuts. While the bulk of Medicaid coverage is exempt from the limit, some so-called “optional” coverage that provides essential health care could end up on the chopping block. Such services include assisted living for low-income seniors and home and community-based care services, including physical therapy and specialized mental health support, for seniors and people with disabilities.[5]

- Health coverage for more than a quarter-million children would be at risk. Part of Florida KidCare, Florida’s umbrella health program for children, provides health coverage to 277,000 children who are ineligible for Medicaid, so this coverage is subject to the Amendment 3 cap. Under Amendment 3, downward pressure on state revenues would mean that the children who rely on these health services[6] could face higher copayments or lose part or all of their coverage.

- Amendment 3 puts at risk health services for elderly residents not covered by Medicaid. Seniors who are ineligible for Medicaid receive state-funded services like home health care, counseling, medical care for those with Alzheimer’s or other memory disorders, and certain medical supplies. [7] Those services would fall under Amendment 3’s revenue cap.

- Amendment 3 puts at risk reimbursements to Florida’s hospitals. Florida’s hospitals estimate that they spent $3 billion in 2009 on uncompensated medical care, including care for uninsured individuals who are medically needy but ineligible for Medicaid based on their income.[8] The state partially reimburses hospitals (and some physicians) for those costs with funds raised through a hospital tax and deposited into a designated trust fund. The revenue raised for this trust fund would fall under the Amendment 3 cap, so hospital reimbursements would be a potential target for cuts.

Florida’s roads, highways, bridges, and public transportation systems are an essential element of the state’s economy, supporting tourism, helping farmers and manufacturers move goods to market, and getting people to work. Likewise, the construction and maintenance of public schools and university facilities support children’s learning and the development of the state’s future workforce. Amendment 3 would make such projects increasingly unaffordable.

Like other states, Florida issues bonds to finance infrastructure investments that can strengthen the state’s economy in the long run. For example, the state issues bonds to finance school or university construction and renovation, the building of roads, bridges, and public transportation systems, and the acquisition of lands for preservation and restoration of water sources and nature preserves (such as the Everglades).

Enactment of Amendment 3 would place the state’s bond rating at risk of a downgrade, which would raise the state’s cost of borrowing for these important infrastructure projects. That’s because state revenues used to make interest payments would be subject to the Amendment 3 limit and would have to compete with other state funding obligations for increasingly limited funds. From the perspective of potential investors and credit-rating agencies, this creates the specter that the state could default on its debt.

The cost to the state of this perceived risk could be large. A substantial body of research finds that limits on state revenues, particularly those that are highly restrictive, have a negative impact on credit ratings and raise the cost of financing infrastructure investments.[9] One extensive study found that “revenue limits . . . tend to increase borrowing costs because they hamper the state’s perceived ability to pay its long-term debt. . . . States with binding revenue limits pay, on average, 17.5 basis points more on their general obligation debt than states without such limits.”[10] If that finding held for Florida, it would mean an additional $1.75 million in annual debt service for every $1 billion in new bond sales. Outstanding Florida bonded debt in 2011 was almost $22 billion, for school and university construction, roads, bridges, transportation projects, water pollution control, and conservation.[11] This suggests annual costs resulting from Amendment 3 could reach $38 million or more, reducing the state’s ability to finance infrastructure and other services.[12]

The impact on bond ratings and interest costs could be immediate upon passage of Amendment 3, beginning with the state’s very next bond issuance. This is because bond repayment periods are typically 15 to 30 years, so bondholders and rating agencies take a long-term view of state finances; Amendment 3’s future effects on the likelihood of default would show up much sooner in the interest rate that investors demand.

Florida levies fuel taxes and motor vehicle fees to pay for the maintenance of highways, airways, ports, and public transit systems. Once the Amendment 3 cap kicked in, these revenues would be restricted and it would become increasingly difficult to keep up with the state’s growing needs.

Already Florida’s Department of Transportation estimates that the state’s unfunded needs between 2010 and 2040 amount to $131.2 billion;[13] over time, the Amendment 3 cap would put Florida further and further behind its goals. The same would be true for revenues collected to maintain the state’s water quality and many natural resources.

Colorado, the only state that has ever placed a population-plus-inflation limit on revenues in its constitution, offers a real-life example of how Amendment 3 would likely affect Florida’s school, health care, and road funding. In the 12 years following TABOR’s 1992 adoption, it contributed to deterioration in the availability and quality of nearly all major public services. Disturbed by the harm TABOR was causing, Colorado business and civic leaders led a successful campaign to suspend the limit beginning in 2006.[14]

- Under TABOR, Colorado cut K-12 education funding. Between 1992 and 2001, Colorado fell from 35th to 49th in the nation in K-12 spending as a percentage of personal income.[15] During that same period, Colorado’s average per-pupil funding fell from $379 to $809 below the national average; by 2006, per-pupil funding was $988 below the national average.[16]

- Under TABOR, Colorado cut higher education funding. Under TABOR, higher education funding per resident student dropped by 31 percent, after adjusting for inflation. Between 1992 and 2001, Colorado’s college and university funding as a share of personal income fell from 35th to 48th in the nation, a ranking it retained at least through fiscal year 2008.[17]

- Under TABOR, Colorado cut funding for public health programs. Between 1992 and 2002, Colorado declined from 23rd to 48th in the nation in the percentage of pregnant women receiving adequate access to prenatal care. Colorado also plummeted from 24th to 50th in the nation in the share of children receiving their full vaccinations. After investing additional funds in immunization programs, Colorado improved its ranking to 23rd in 2008. [18]

Colorado’s economy is stronger than Florida’s, but the reasons have nothing to do with TABOR. The strength of Colorado’s economy is largely a legacy of a post-World War II public investment boom by the federal government, including the military.

The federal investment left Colorado with a strong infrastructure of high-tech firms and researchers, a young, highly educated workforce, and public universities with well respected science and technology programs. By 1991, a year before TABOR’s adoption, more adults in Colorado had completed at least four years of college than in any other state.

Other advantages, such as energy resources, natural beauty, a location in the center of the country, and massive public investment in a new Denver airport, have also helped create a strong economy.a

TABOR did not contribute to Colorado’s success. A study by two prominent economists in the area of state and local public finance found that Colorado’s growth during the first decade under TABOR was roughly the same as it would have been without TABOR. The study used statistical analysis to control for factors other than TABOR that could affect economic growth.b

a “Education and Investment, Not TABOR, Fueled Colorado's Economic Growth in 1990s,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 23, 2006, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2497. b Kim Rueben and Therese J. McGuire, “The Colorado Revenue Limit,” Tax Policy Center, April 6, 2006, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/url.cfm?ID=1000940.

- Under TABOR, Colorado cut funding for roads, highways, and transportation. According to the Colorado Transportation Finance and Implementation Panel, TABOR kept lawmakers from increasing the gas tax, which was needed to keep pace with the rising costs of construction, and from making reliable transfers from the state’s general funds.[19] As a result, the panel projected that the share of the state’s highways in good or fair condition will fall to just 40 percent by 2016.

- TABOR failed to help the Colorado economy and may have made it harder for the state to recover from the 2001 recession. Under TABOR, Colorado saw slower job growth than other Rocky Mountain states.[20] Colorado also fared worse than its neighbors in the wake of the 2001 recession: between March 2001 and January 2006 (when TABOR was suspended), job growth in Colorado was 0.2 percent, just a fraction of the 9.3 percent average for the eight Rocky Mountain states.

Colorado Business and Community Leaders View TABOR as Deeply Flawed

A wide range of Coloradoans — business leaders, higher education officials, children’s advocates, and legislators of both parties, among others — recognize that TABOR has limited the state’s ability to fund critical services.

- “Coloradoans were told in 1992 . . . that [TABOR] guaranteed them a right to vote on any and all tax increases. . . . What the public didn’t realize was that it would contain the strictest tax and spending limitation of any state in the country, and long-term would hobble us economically.” — Tom Clark, Executive Vice President, Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation

- “The [TABOR] formula . . . has an insidious effect where it shrinks government every year, year after year after year after year; it’s never small enough. . . . That is not the best way to form public policy.” — Brad Young, former Colorado state representative (R) and Chair of the Joint Budget Committee

- “[Business leaders] have figured out that no business would survive if it were run like the TABOR faithful say Colorado should be run — with withering tax support for college and universities, underfunded public schools and a future of crumbling roads and bridges.” — Neil Westergaard, Editor of the Denver Business Journal

Colorado business leaders successfully campaigned to suspend the TABOR formula for five years beginning in 2006 and permanently change some of its most damaging features. Although the suspension now has technically expired, Colorado revenues and services remain well below the TABOR limit.

The failure to regain services during the suspension reflects the difficulty of generating enough annual revenue to improve services in the aftermath of so many years of revenue starvation. Colorado would need robust and sustained revenue growth to go beyond maintaining its current, low level of services and begin to recoup lost ground.[21]

Colorado’s experience provides Florida and other states with an important cautionary tale. Thus far, lawmakers and voters have heeded that caution. TABOR has been rejected by legislators in the more than 30 states that have considered it and by voters in the four states where it made it to the ballot.

When Colorado adopted TABOR, it ranked in the middle of the pack among states on a number of measures of key public services; under TABOR, it fell to the bottom on many of those rankings. Florida already ranks among the lowest-performing states on a range of measures:

- 50th in spending on K-12 education as a share of personal income and 38th in spending per pupil, which is more than $1,700 below the national average;[22]

- 36th in student-to-teacher ratio;[23]

- 44th in high school graduation rates;[24]

- 43rd in higher education funding per $1,000 of personal income;[25]

- 49th in its percentage of low-income, nonelderly adults with health insurance;[26] and

- 50th in its share of low-income children with health insurance.[27]

Amendment 3 would make it extremely difficult for Florida to improve these rankings, and over time it would likely push the state even further behind. Since Florida’s future prosperity depends in part on having an educated and healthy workforce, losing further ground in these areas would weaken the state’s long-term economic prospects.

Amendment 3 reduces legislative accountability. Most of the current Florida legislators who placed Amendment 3 on the November ballot would not have to implement the budget cuts that it would require, because they will no longer be in office when it would take full effect several years from now. (Florida has eight-year legislative term limits, and the first budget vote under Amendment 3 when it is in full effect would not occur until 2018.) Rather, that painful task would fall to their successors.

Those successors would find it difficult to muster the supermajority vote of each house that would be required to override the limit when it takes full effect.

Supermajority requirements can be a recipe for gridlock. Until very recently, California required a supermajority vote in each house of the legislature to enact its annual budget — the only major industrial state (and one of only three nationwide) to have such a requirement. This requirement was widely blamed for California’s perennial difficulty in passing a budget. As the Los Angeles Times noted, “Supermajority budgeting rules … have all but brought state government to a standstill.”

Supermajority budget rules also increase the power of individual legislators to demand state funding for pet projects in return for providing the necessary votes so that revenue-raising legislation can obtain supermajority support. To be sure, such vote-swapping can occur under simple-majority rules as well. But as a blue-ribbon bipartisan body in California (the California Citizens Budget Commission) noted, the degree of vote-swapping tends to intensify with the level of difficulty of obtaining the necessary votes to pass a budget. The Commission also found evidence that California’s supermajority rule led to enactment of “pork-barrel” legislation.

Responding to the problems that California’s supermajority requirement created, voters removed it from the constitution in November 2010. In both 2011 and 2012, California enacted on-time budgets — the first time in over a decade (and only the second time in 25 years) that California enacted back-to-back, on-time budgets.[28] Amendment 3 could bring to Florida the legislative dysfunction that California historically has been known for.

Like Colorado’s TABOR, Amendment 3 would limit state revenues to a formula based on growth in overall population and inflation. This formula does not allow a state to maintain, even in prosperous times, the same level of programs and services it now provides. Both parts of the formula have serious shortcomings when applied to state revenues:

- Population. The specific population groups most likely to need public services tend to grow more rapidly than the overall population.[29] An example is senior citizens. According to Florida’s Office of Economic and Demographic Research, Florida’s total population is projected to increase by 27 percent from 2010 to 2030, while its 65-and-older population is projected to increase three times as fast, increasing by 87 percent.[30] As Florida’s elderly population — which will be a quarter of its total population in 2030 — grows, so will the cost of maintaining the current services the state provides many of them, such as Meals on Wheels, care for those with Alzheimer’s or other memory disorders, vouchers to address home heating or cooling emergencies, and in-home care subsidies to help cover the expenses of food, clothing, or medical incidentals not covered by Medicaid.

Under Amendment 3, Florida could maintain services to the elderly (or expand them to meet growing need) only if residents were willing to cut other areas of the budget, such as education. These are the types of choices that a TABOR limit would impose on lawmakers. - Inflation. The inflation measure that Amendment 3 uses is the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), a nationwide statistic calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The CPI-U measures the change in the total cost of a “market basket” of goods and services purchased by an average consumer in a U.S. city. Since most urban households spend a majority of their income on housing, transportation, and food and beverages, those items are the primary drivers of the CPI-U. By contrast, the state of Florida spends its revenue primarily on education, health care, corrections, and roads. In short, the market baskets of spending are entirely different.

Indeed, the items in the “basket of goods” most heavily purchased by states — such as health care, K-12 and higher education, child care, and early education — have seen significantly greater cost increases in the past decade than the items in the basket of goods purchased by urban households. That trend is expected to continue.[31]