- Home

- Federal Tax

- Tax Reform Should Raise Revenues — And C...

Tax Reform Should Raise Revenues — And Certainly Should Not Lose Them

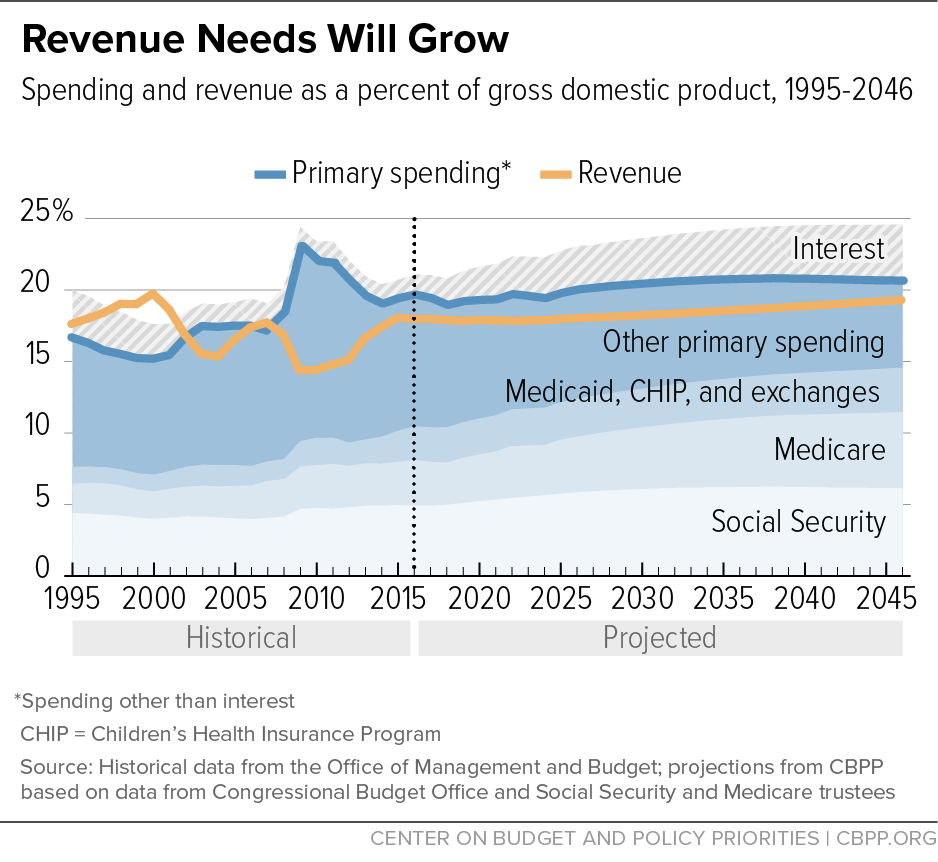

The federal government needs a tax system that provides adequate revenues to finance critical national needs and avoid spiraling debt and interest burdens. The long-term fiscal outlook has improved substantially in recent years, but further steps are needed to reduce projected deficits and debt. Without a change in policies, the ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) — 77 percent at the end of 2016 — will gradually grow to 102 percent by 2036 and 113 percent by 2046.[1]

To address these budgetary pressures, federal tax reform proposals should aim to increase revenues. Otherwise, the entire burden of reducing the deficit to prevent unsustainable debt levels will fall on federal programs, including Social Security and Medicare. Programs for low- and middle-income households shouldn’t be cut to pay for tax cuts favoring those at the top of the income scale. Failure to raise revenue will also preclude new investments in infrastructure, education, and other areas.

At a bare minimum, tax reform should not lose revenues, either in its first decade or beyond. Key Republican congressional leaders have promised that tax reform will be revenue-neutral. They should be held to that promise — measured using standard revenue estimates and without accounting gimmicks.

Several Factors Are Placing Pressure on Spending

Three factors will place upward pressure on federal spending in coming years:

-

Existing commitments for Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid will cost more as the population ages and health care costs continue to rise in both the public and private sectors. The share of the population that is 65 or older will grow from 15 percent to 21 percent over the next 20 years and inch up thereafter. As a result, spending for Social Security and the major health programs is projected to grow from 10.4 percent of GDP in 2016 to 13.9 percent by 2036 and 14.6 percent by 2046, and total federal spending will rise at a similar pace. (See Figure 1.)

- Relief from the 2011 Budget Control Act’s overly austere caps on defense and non-defense discretionary (NDD) spending is required to avoid shortchanging critical activities. Recent deficit-reduction efforts have focused disproportionately on the parts of the budget controlled by the annual appropriations process. This has squeezed spending for NDD activities to levels that are — or will soon become — too low to sustain without risking damage to areas important to long-term economic growth, such as research, education, and job training.

- Resources will be needed to address critical unmet needs, such as infrastructure, and pay for new initiatives that the federal government might undertake. These could include proposals to make college more accessible and affordable, expand employment and training programs, establish a program of paid family leave, increase the earned income and child tax credits, and insure against the cost of long-term health care services and supports.

Tax Reform Should Raise Revenues

Federal tax reform proposals generally aim to cut marginal personal and corporate income tax rates and offset the cost, in whole or in part, by limiting tax deductions, exclusions, and other tax breaks known collectively as “tax expenditures.” However, applying the savings from curbing tax expenditures exclusively to reducing tax rates would exhaust what may be the most promising and politically feasible options for increasing revenues. That would effectively take revenue-raising off the table for deficit reduction for years to come, placing the burden of deficit reduction entirely on federal programs.

Social Security and Medicare will be especially vulnerable because they account for most of the projected growth in federal spending, even though that growth stems primarily from the aging of the population and rising health care costs, not from more generous benefits. Critics’ disingenuous claims that benefits must be cut in order to “protect” or “preserve” these programs will only intensify if insufficient revenues allow the debt to climb faster than GDP. House Republican leaders have used such claims to justify their plan to radically restructure Medicare by converting it to a premium support, or voucher, system and raising its eligibility age.

Programs for low- and moderate-income households will also be a prime target of budget cuts, as they have been in recent congressional Republican budget plans, if revenues are inadequate. To minimize threats to Social Security, Medicare, and low-income programs — and to restore some of the recent cuts in defense and NDD spending while leaving room for needed initiatives — tax reform effort should raise revenue.

At the Very Least, Tax Reform Should be Revenue-Neutral

While raising revenue is the preferred approach for tax reform, it should, at the very least, be revenue-neutral — that is, it shouldn’t lose revenues over the first decade or in subsequent decades. In achieving that goal, policymakers should use honest estimates of the impact of tax reform. Specifically:

- They should resist the temptation to use budget gimmicks, such as timing shifts that increase revenues in the short run but reduce them in the long run.

- They should use traditional budget estimates, from Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation, that do not attempt to quantify the highly uncertain effects of tax changes on the overall size of the economy. That’s the prudent approach. Policymakers are very unlikely to raise taxes to make up for any revenue shortfall if predicted economic gains do not materialize. If the gains do materialize, and tax reform generates higher revenues, it would be better to dedicate those revenues to reducing the deficit than to lowering tax rates.

Several congressional leaders — notably House Speaker Paul Ryan, House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell — have said that tax reform should be revenue-neutral. This means that any tax reductions should be offset by tax increases, not by budget cuts. Any savings from federal programs should be used to finance needed initiatives and contribute to long-term deficit reduction, not to make tax cuts larger.

Tax Cuts for the Rich Aren’t an Economic Panacea — and Could Hurt Growth

Policy Basics

Federal Tax

End Notes

[1] For more detail and references, see Paul N. Van de Water, Tax Reform Must Not Lose Revenues — and Should Increase Them, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 20, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/tax-reform-must-not-lose-revenues-and-should-increase-them.