President Trump’s budget includes deep spending cuts that would create hardship for millions of low- and moderate-income people, alongside massive tax breaks targeted to the most well-off. Numerous CBPP analyses have detailed the effects of these “reverse Robin Hood” proposals.[1] This analysis unpacks the budget’s spending and tax proposals and highlights the unrealistic assumptions that mask the budget’s true effects.

The Administration depicts its policies as reducing deficits by $5.6 trillion over the decade, sufficient to balance the budget in 2027, with only a fraction of the savings coming from cuts to health and low-income programs. The budget also shows that the President is proposing $990 billion in revenue losses. But this presentation hides two important facts.

First, for President Trump’s signature tax plan, the budget shows no net impact on revenues. That is, it simply assumes that unspecified revenue-raising provisions would offset the more than $5 trillion cost of his proposed tax cuts, even though the Administration has not proposed tax policies that could plausibly offset that cost.

Second, the budget assumes that the extra economic growth sparked by the Administration’s policy proposals would reduce deficits by $2.1 trillion over the decade. This “economic feedback” bonus is based on a rosy assumption that economic growth will rise to 3 percent per year by 2021, a rate that most economists find highly implausible.

Table 1 offers a more comprehensive picture of the President’s budget policies, including the cost of his tax plan. It shows:

- The budget gets about three-fifths of its spending cuts from programs assisting people with low and moderate incomes, even though these programs only account for roughly one-quarter of total federal program spending.

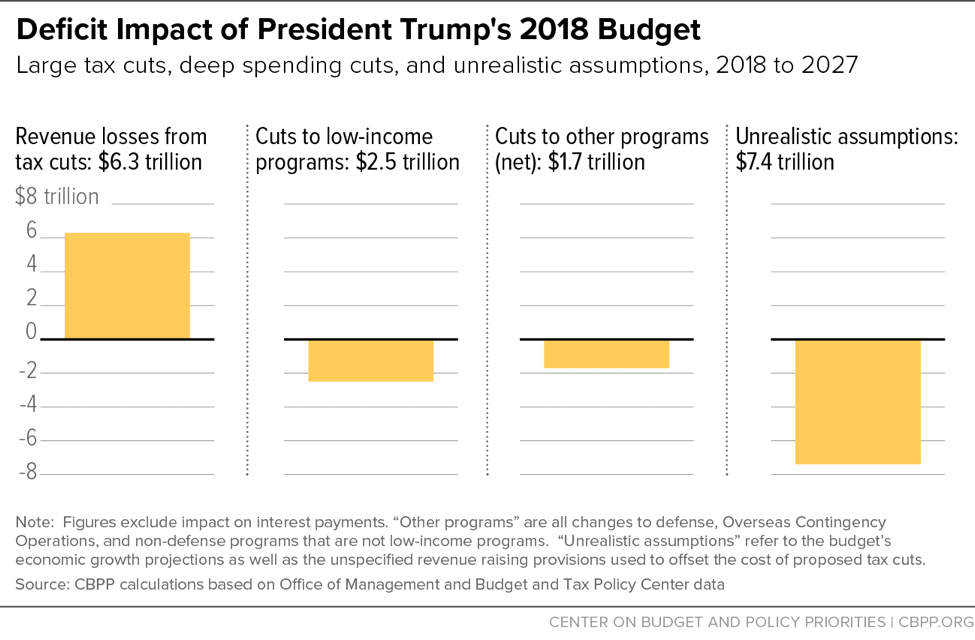

- The budget’s total specified spending cuts, though draconian, are nevertheless overwhelmed by the cost of the proposed tax cuts (see Figure 1).

- If one removes the budget’s unrealistic assumptions regarding economic growth and offsets for its tax cuts, the budget increases deficits by $2.5 trillion over the decade, rather than reducing them by $5.6 trillion as the Administration claims.

The Trump budget calls for a total of $4.2 trillion in cuts to both discretionary and mandatory programs over the coming decade.[2] In total, non-defense programs would be reduced by $4.3 trillion and defense programs would be increased by $27 billion (when the reductions to Overseas Contingency Operations are taken into account, as discussed below).

These budget cuts are disproportionately focused on programs that serve struggling families. Overall, programs that assist people with low and moderate incomes would be reduced over the next ten years by $2.5 trillion, including $2.1 trillion in cuts to entitlement programs and $400 billion in cuts to non-defense discretionary programs. These programs would absorb about three-fifths of the budget’s total cuts, even though they account for only about one-quarter of total program spending.[3]

The Trump budget would cut non-defense discretionary (NDD) spending by $1.8 trillion over the decade. Virtually all of this total reflects reductions in NDD programs subject to the caps imposed by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA). These programs cover a wide range of government functions, including scientific research, aid for local schools, job training, housing assistance, food safety and infectious disease control, environmental protection, and international assistance. Relative to current funding levels, the budget would reduce NDD programs by 41 percent by 2027, after adjusting for inflation.[4] These cuts would intensify the cumulative impact of seven years of austerity under the BCA’s tight annual appropriations caps and sequestration.[5]

Of the total NDD reduction, $400 billion reflects cuts in programs for low- and moderate-income people. In 2018 alone, the budget would cut major job training grants to states and communities by 40 percent, eliminate housing vouchers for more than 250,000 lower-income households, and end the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps poor households pay their heating bills.[6]

The NDD reduction also includes a $95 billion cut in Highway Trust Fund (HTF) spending and a $151 billion reduction in Overseas Contingency Operations or OCO (largely State Department programs); neither of these areas are subject to the BCA caps.

In comparison, defense spending would increase by $27 billion over ten years. Although the budget would raise spending on defense programs subject to the BCA caps by $469 billion, it would largely offset that increase by cutting OCO spending by $441 billion.

Mandatory Spending

The budget would cut mandatory spending by $2.5 trillion over ten years. Of this, $1.25 trillion comes from the House-passed bill to replace the Affordable Care Act[7] and $615 billion comes from additional cuts to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. The House-passed bill would increase the number of people without health insurance by 23 million, raise out-of-pocket health costs for millions more, and substantially weaken key protections for people with pre-existing conditions. Like the House bill, the budget would convert Medicaid into a per capita cap or, at state option, a block grant, but then would cut it considerably more deeply than the House bill by lowering the per capita growth rate and letting states cut their programs in ways they aren’t permitted to do now. Medicaid spending alone would be cut nearly in half (47 percent) by 2027.

Outside health care, the budget would cut $270 billion from entitlement programs that serve low-income Americans, including $193 billion from SNAP (formerly food stamps), $22 billion from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and $9 billion from Supplemental Security Income. [8]

The budget’s remaining changes to mandatory spending would achieve $343 billion in net savings, including cuts to disability programs (including Social Security Disability Insurance), student loans, civil service pensions, and savings from a claimed government-wide reduction in improper payments. This part of the budget also includes $200 billion in undefined spending for infrastructure, but the increase is temporary, while the cuts in the Highway Trust Fund (mentioned above) are permanent. After a few years, the net impact of these two proposals would be large and growing cuts in infrastructure spending.[9]

The Trump budget shows revenue losses adding $990 billion to deficits over ten years. This largely stems from the budget’s endorsement of the House bill to “repeal and replace” the ACA. The bill would repeal the ACA’s tax provisions, thereby delivering billions in tax cuts to the wealthy — with households making more than $1 million a year ultimately receiving annual tax cuts averaging more than $50,000 apiece.[10]

The budget does not show the effects of the Trump Administration’s tax plan. In April, the Administration unveiled a tax proposal that would provide costly tax cuts for the wealthy while offering vague promises to working families and few specifics on how the cost of tax cuts would be offset.[11] The proposal would cost roughly $5.3 trillion over the decade, in addition to the $1 trillion in revenue losses from the House-passed health bill.[12] Even after taking into account the Administration’s proposed restrictions on itemized deductions, the top 1 percent of households would still receive annual tax cuts of at least $250,000 from the Trump tax plan, according to CBPP calculations based on Tax Policy Center estimates.[13]

Although the budget offers no new details about the tax plan and assumes it would have no net impact on revenues, it does assume that the tax plan (and other Administration policies) will boost economic growth and help reduce the deficit by $2.1 trillion over the decade (discussed in more detail below). There has been much discussion about whether the Administration is claiming that these positive “economic feedback” effects will both reduce the deficit and pay for its tax plan — that is, whether it is double counting these effects. Some statements suggest that the Administration is indeed double-counting the assumed economic feedback effects,[14] while others suggest that the Administration is assuming that the tax cuts would be offset entirely by limiting deductions and curbing tax avoidance (though it has not provided details of measures to achieve that outcome).[15] Either way, the bottom line is that the budget assumes $5.3 trillion in additional revenue to pay for the tax cuts the President has proposed — without offering a plausible explanation of where that additional revenue would come from.

Absent these assumed offsets, the budget would show a total revenue loss of $6.3 trillion over the decade, rather than the $990 billion presented in its documents.

The budget assumes that the economy will grow by 2.9 percent per year, on average, over the decade. Because higher economic growth improves the fiscal outlook by increasing revenues and lowering spending, the budget claims “economic feedback” that lowers the deficit by $2.1 trillion over the coming decade.

But the Administration’s growth forecast is out of line with other forecasts. For instance, it is 1.1 percentage points more per year than the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) assumes. This large gap between the Administration and CBO forecasts is unprecedented, CBPP found, going back to the late 1970s. And the gap is particularly large when compared with forecasts by other recent administrations.[16]

Economic projections over the decade rest on assumptions about the growth in the size of the labor force and its productivity. CBO and other analysts project that labor force growth will slow in the next decade as the baby boom generation retires, absent a substantial increase in immigration (which seems contrary to this Administration’s policies). Achieving the economic growth the Administration claims without a significantly larger contribution from labor force growth would require productivity to grow more than twice as fast as CBO projects over the next decade — and faster than in any sustained period since World War II.[17]

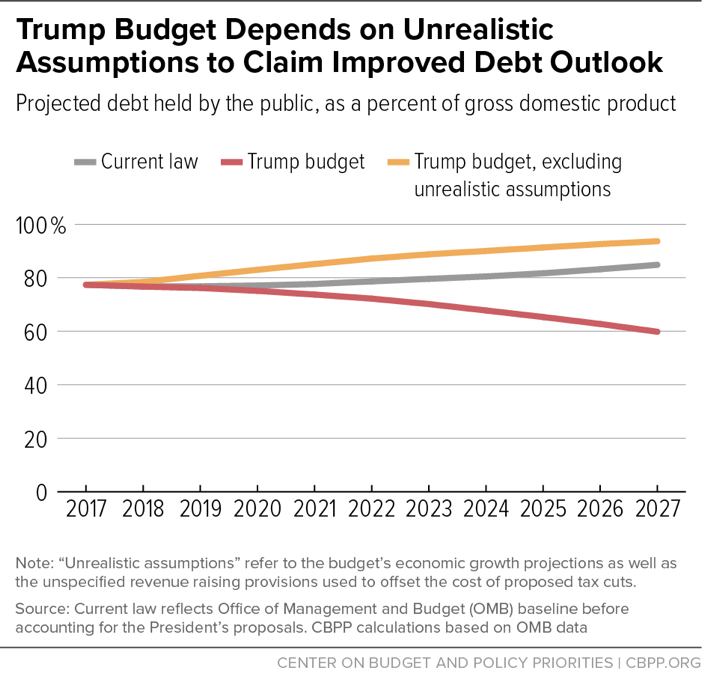

As Table 1 shows, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects deficits will total $8.8 trillion between 2018 and 2027, assuming current spending and revenue laws and no policy changes. Under these current-law assumptions, debt held by the public would rise from 77 percent of the economy this year to 85 percent in 2027.[18] The budget then asserts that the Administration’s proposals would reduce the projected deficit by $5.6 trillion over the next decade, produce a balanced budget in 2027, and significantly scale back the debt ratio by the end of the decade.

However, these claims rest on two large, highly unrealistic assumptions, as discussed above. First, the budget includes rosy economic growth projections, which lower its ten-year deficits by $2.1 trillion. Second, the budget simply assumes that its tax cuts of $5.3 trillion will be offset by other, unspecified, revenue-raising provisions. These unrealistic assumptions total $7.4 trillion and, when the associated interest costs are included, $8.1 trillion. With these unrealistic assumptions removed, deficits would in fact increase by $2.5 trillion over the decade relative to current law. As a result, the debt-to-GDP ratio would climb to 94 percent in 2027.[19] (See Figure 2.) In other words, rather than produce trillions in savings, the budget would actually hurt the nation’s financial position.

This analysis raises issues with some of the assumptions and presentations in the Trump Administration’s fiscal year 2018 budget. We rely almost entirely on the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimates used in that budget, largely because a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of the budget is not yet available. Only in selected instances, such as for the cost of the Trump tax plan, do we use estimates other than those prepared by OMB.

CBO is expected to release its analysis of the Trump Administration budget in mid-July. As part of that analysis, CBO will assess the Administration’s economic forecast and the effects of its individual policy proposals on spending, revenue, deficits, and debt, and will produce its own estimate of the President’s budget policies.

When CBO looks at the Administration’s economic assumptions, for instance, it will examine more than just how fast the economy is expected to grow (which has been the focus of this analysis). It will also assess other economic variables, such as inflation and interest rates, that also influence budget estimates.

When estimating the effects of a policy proposal, CBO relies on details of the proposal provided in the budget. If the budget lacks sufficient details about a policy, then CBO typically does not provide an estimate. This will likely be the case for the Administration’s tax reform proposals, where the budget provides few details. If CBO does not estimate the Trump tax plan, its analysis will effectively show that the plan has no impact on revenues — just as the Trump budget claims. But this does not mean that CBO agrees with the Administration’s claim, only that CBO lacks sufficient details to estimate the effects of tax policy.

For this analysis, we provide estimates of the tax proposals that the Administration has emphasized (and which President Trump detailed during the campaign) but not the proposals — largely revenue-raising provisions — that the Administration merely assumes and has provided scarce details on.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Deficit increases (+) or decreases (-) in billions of dollars |

2018-2027 |

|---|

| Deficits in OMB pre-policy (current law) baseline |

$8,775 |

| Proposals in FY 2018 Budget: |

|

| Discretionary spending |

|

| Non-defense |

-$1,791 |

| Low-income programs |

-$400 |

| Other non-defense programs |

-$1,144 |

| Highway Trust Fund* |

-$95 |

| Overseas contingency operations (OCO)* |

-$151 |

| Defense |

$27 |

| Defense (excluding OCO) |

$469 |

| OCO* |

-$441 |

| Subtotal, discretionary spending |

-$1,763 |

| Mandatory spending |

|

| Repeal and replace Affordable Care Act |

-$1,250 |

| Additional cuts in Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Plan |

-$615 |

| Additional cuts in low-income programs |

-$270 |

| Other policy changes |

-$343 |

| Subtotal, mandatory spending |

-$2,478 |

| Subtotal, discretionary and mandatory spending |

-$4,242 |

| Revenue |

|

| Repeal and replace Affordable Care Act |

$1,000 |

| Trump tax plan |

$5,300 |

| Offsets for Trump tax plan |

-$5,300 |

| Other (net) |

-$10 |

| Subtotal, revenue |

$990 |

| Debt service |

-$311 |

| Economic feedback |

-$2,062 |

| Total deficit reduction |

-$5,625 |

| Deficits in the FY 2018 budget |

$3,150 |

| Addendum: Unrealistic assumptions in budget |

|

| Economic feedback |

-$2,062 |

| Offsets to Trump tax plan |

-$5,300 |

| Subtotal, unrealistic assumptions |

-$7,362 |

| Debt service (Trump tax plan) |

-$783 |

| Total deficit increase, excluding unrealistic assumptions |

$2,520 |

| Deficits in the FY 2018 budget, excluding unrealistic assumptions |

$11,295 |